Cologne Ranger

Two rivals brought to perfect pitch in a year-long manufacturer arms race. We let loose in Ford’s secret weapon, and ask what made it great For many - myself included…

I guess it means different things to different people. To my father’s generation Brabham was a person long before it was a racing car company. Jack – tough as they came both on and off the track, a no- nonsense engineer from Down Under who came over here and showed the Poms how it was done with back-to-back world titles.

To me Brabham meant something else: a series of sleek and innovative grand prix cars of the late 1970s and early 1980s showcasing the mercurial talents of Gordon Murray. Fan-assistance, surface cooling, hydro-pneumatic suspension… whether it worked or not, I just loved the sheer inventiveness of those cars and the fact they always managed to look so, well to my young eyes, cool.

So, I wonder what Brabham will mean to the young of today? If you’re Jack’s son, David, he hopes the answer is staring you in the face right now. After years of legal battles simply to regain control of his family name and years more of fundraising and development, the first Brabham since the Formula 1 team slipped under the waves back in 1992 is here.

Although just 70 of these BT62s will be built (£1.2million if you’re in the market), it is absolutely not a Led Zeppelin one-night-only return to the stage. Brabham, David tells me, is back. Next will come a road car including unspecified design elements of the BT62, and that, rather than this as you may have read elsewhere, is the car that will be homologated into the GTE category to be raced at Le Mans as soon as 2021.

So, the BT62 is a stepping stone, a large, powerful and conspicuously good looking stepping stone to my eyes, but a stone nonetheless. “People need to understand our plans. My intention is for Brabham to be a manufacturer of high-performance road cars,” David tells me one sunny day at Silverstone. “But we have to be able to grow the business to a point where we can raise the money to build the road cars. Racing feeds off the back of that.”

The BT62 will compete, probably in invitational categories because it couldn’t be homologated as a GT3 car, just because David wants to see Brabham competing once more: “Racing is in the blood. My initial idea when we got the name back was for Brabham to be a race team. But then I thought there was the opportunity to do something more substantial, more adventurous than that. Happily our partners at Fusion Capital in Adelaide [which Brabham Automotive is part of] agreed.

“If we can build an automotive group that will then support a race team, that would be the best of all possible worlds and mean a sustainable future for Brabham.”

David is not saying how many of the cars are sold but simply that he is “happy with where we are, which is where we expected to be at this stage. We were never going to sell them all at once. People need to understand our long-term plans and be reassured that we’re not going anywhere.”

But all that is for later. Right now, the BT62 is waiting for me, so I asked David what the prime motivations were when deciding on the car’s specification. The answer is refreshingly honest: “I asked myself what car I’d like to drive.”

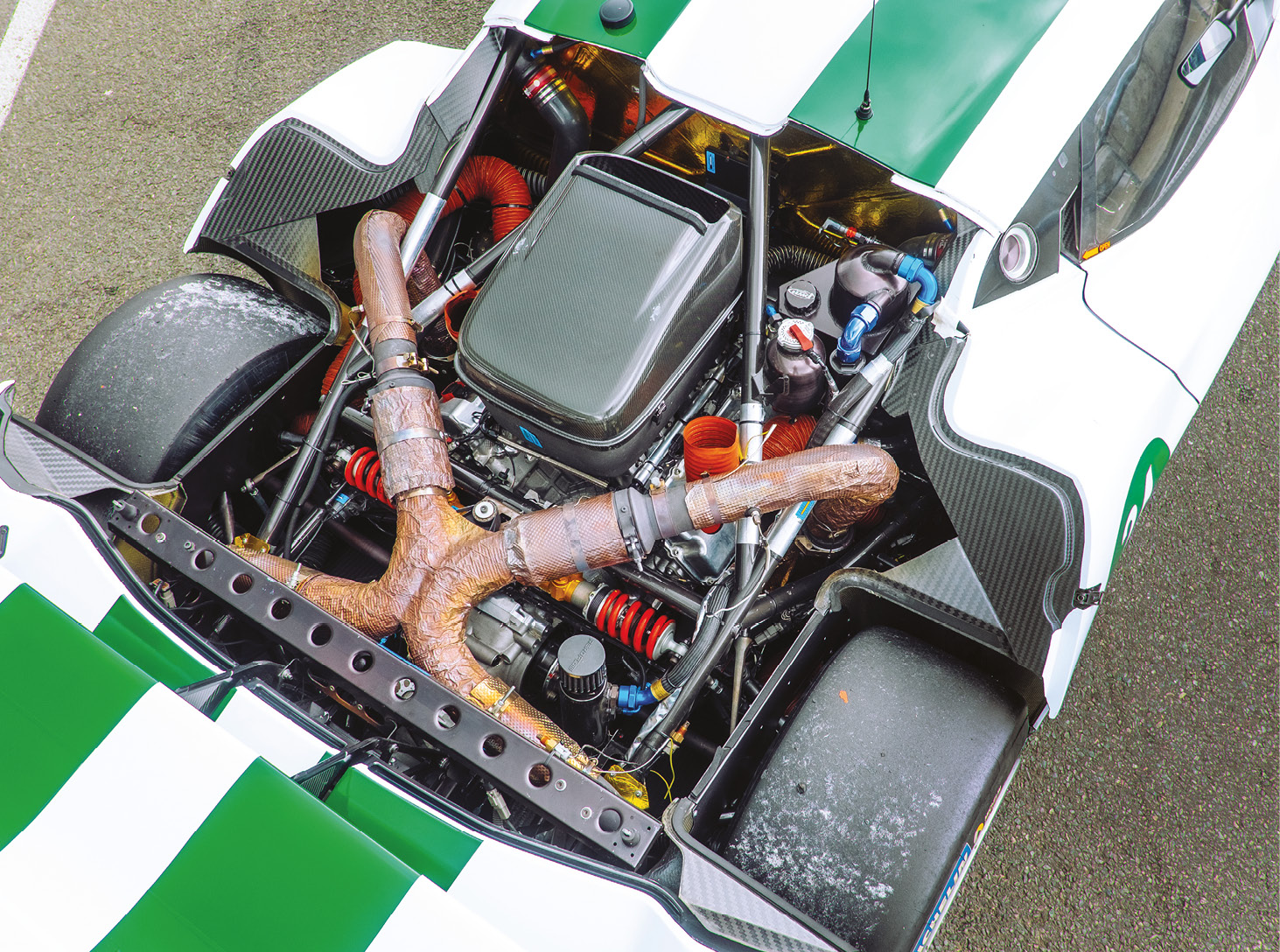

And what David Brabham would like to drive is a two-seat closed-cockpit sports car with less than a tonne of weight, more than a tonne of downforce and a normally aspirated V8 engine developing 700 horsepower. Which sounds fair enough.

Unbound by any race regulations, Brabham has been able to design an engine entirely to its own specification, save the most basic building element in the form of a Ford V8 block.

“It’s not unlike what Dad did,” David muses, referring to how Repco transformed an engine that started life as an Oldsmobile road car unit into a Formula 1 engine capable of winning back-to-back constructors’ titles. By boring the 5-litre Ford block out to 5.4-litres and fitting new internals, an engine that produces a little more than 400bhp in the standard Ford Mustang now yields the aforementioned 700hp, or 691bhp for any pedants there may be among you.

“It could end up being five or six seconds faster than GT3 cars”

It runs through a six-speed sequential Holinger race gearbox to the rear wheels where it directs its torque to the road via massive Michelin slicks located by double-wishbone pushrod suspension. Braking is via carbon-on-carbon discs. With 1200kg of downforce pressing a 972kg car into the track at 167mph, this is a very serious piece of kit indeed. Serious enough, indeed, to circulate Bathurst three seconds below the GT3 race lap record despite, “leaving a few seconds in our pocket” as David puts it. Looking at the onboard video you can easily see where another couple of seconds can come from, and the car is still being developed. If it ends up being five or six seconds per lap quicker than frontline GT3 pace I’d not surprised at all, although it might need then to be pegged back a touch before the GT3 manufacturers are happy to let it race alongside them.

It’s an easy car to access thanks to quite a low sill, a removable wheel, a sliding pedal box and a fixed seat. It feels very comfortable, reassuring even, with decent visibility and information clearly displayed on a single, colour, high-definition screen. I extend quite a lot further than David does in all three dimensions, but it feels like it could have been built for me.

David leans in: “The car is quick. You’ll notice that,” he announces with masterly understatement. “The only thing I’d advise you to do is try the brakes on the straight first, just so you know what they feel like.” Not one word about bringing his, to him, near-priceless development prototype back in one piece. Right now the only other cars in existence are a show car and the first customer’s car

Master on, ignition on, thumb the starter and, for want of a better word, ‘ka-boom’. My whole world erupts as ground-trembling V8 thunder breaks out all around me. I know turbos give lots of readily accessible power and are terribly clever, but they can’t do this. It is a ridiculously brilliant noise, far closer to that of a Ford GT40 than most modern GT3 cars. I could sit here for some time, but the water temperature is rising. I clonk into gear, lift the surprisingly gentle clutch and head out to discover more.

The first point of note, which you detect almost at once and whose impression only grows as you gather speed and familiarity, is how unlike a GT3 race car this is. Perhaps because it’s a Brabham with slicks and wings I’d expected it to be utterly uncompromising, unpleasant even, when not being driven fast. It’s not like that at all.

Not that you’d choose to, but this is a car you could probably drive quite slowly. This is more important than it sounds: Brabham is very aware that his customers are not likely all to come with GT3 levels of skill and experience straight out of the box. To that end he is putting in place quite a comprehensive driver tuition programme where clients will be able to drive road and racing cars of different levels of performance. “One of my passions is to help people get to the next level because that’s how you get to really enjoy it. And it’s as much about instilling the right mental approach as it is driving the car. But sooner or later they’re going to have to saddle up the Brabham, and being able to ease your way into that experience will only bring benefits.”

It’s not a luxury I have today. Brabham has an extensive testing programme to complete and my laps are limited in number. There’s no other option than to drive it fast, straight out of the pit box.

There aren’t many cars capable of this level of performance in which I’d be happy to take such a leap of faith, but the BT62 is so instantly reassuring that driving it rapidly feels entirely natural.

“I love the lack of a torque curve like Ayers Rock: it really builds”

The motor is superb. It feels so different to the throttled-back turbo engines you find in most GT3 cars these days. Indeed, while straight-line performance is by far the most disappointing aspect of any GT3 car, the Brabham’s ability to move you from one end of the straight to the other like a table cloth has been ripped out from under you feels entirely in keeping with the character of the rest of the car.

OK, maybe not quite entirely, but that speaks far more of the fluency of its chassis than it does of any shortcomings in the motor. What I loved most was its lack of a torque curve like Ayers Rock: it really builds as the revs rise, saving the real nuttiness until it’s past 4500rpm. From there to the 7500rpm red line it’s pure party time.

The six ratios are close enough to keep the car on the cam – it’s so nice to be able to talk in such terms again – but I’d say the shift quality could be tightened up a shade, just so it feels as immediate and alive as the engine to which it’s attached. Then again this is the much-thrashed prototype on which development work will continue until first deliveries begin at the end of this year.

It would take a very great deal to cast that powertrain in a supporting role, but the chassis damn near does it. As ever it is the brakes which require the most mental recalibration, not just in the absurd stopping distances they provide but also the immense pedal efforts needed. The car has ABS but when I ask David what his recommended setting is he says “don’t worry, you won’t feel it”, although whether that is courtesy of the power of his brakes or the puniness of my right thigh he is too kind to say. But basically, you drive past what appears to be a natural braking point, past the absolute last braking point, up to the point where you know you’ve just crashed, pause and then brake. And that should guide you neatly into the apex.

Of course, with a car like this, you don’t actually need to unload too much speed, especially if the corner coming up is quick enough to get its wings working. But even through Copse it’s not the apex speed that impresses most, but the precision of the car. Of course, all cars with meaningful amounts of downforce do this and if you’ve never experienced it, you simply won’t believe how floaty and vague even well-developed supercars can feel. But the Brabham has something else too.

It is terrific over bumps and rumble strips: excellent on the way in to a corner, borderline freakish on the way out. There are some quite noticeable undulations where Silverstone’s National Circuit spears right onto the Wellington Straight and while you can feel the BT62 articulating itself over them, its power delivery remains entirely uninterrupted.

I’m so glad David Brabham decided not just on this specification for the BT62 but then also developed it into the car it is today. People will say you can buy a hot Radical and go nearly as fast for a tiny fraction of the £1.2 million this car will cost. And if that’s what matters most to you, go and buy a Radical. I’ve never driven a bad one (apart from its road-going versions). But to me that’s not what this car is trying to do.

Buy a BT62 and you are buying into the Brabham name, both that of the Le Mans-winning, ex F1-driving son and his triple world championship-winning dad. You’re also buying into a name that has adorned some of the most beautiful, innovative and successful formula racing cars of all time. Finally, you’re buying just about the most fun I’ve had driving a modern racing car. I wish David and his team all the luck in the world with it.