SPAX DAMPERS

SPAX DAMPERS Recently introduced by Spax Ltd., of Fortress Road, N.W.5, a range of adjustable hydraulic and telescopic shock-absorbers are designed as replacement units. A pair of the telescopic units…

They symbolised free thinking and innovation, a time when engineers weren’t constrained by the law of the wind tunnel or overly proscriptive rulebooks. Norman Dewis and Robin Herd, who have died aged 98 and 80 respectively, belonged to different generations but were united by a spirit of enterprise.

Dewis will forever be associated with Jaguar, the firm he joined in 1951 and loved ever after. His technical triumphs include developing disc brakes for road use, a process that included the inevitability of occasional failures – with him at the wheel – as there were no simulation tools to help minimise such risks. He set what was then a speed record for a production car – 172.4mph in a lightened, streamlined XK120 on a closed stretch of Belgian motorway – and was also the brains behind the way the C-, D- and E-types, the timeless Mk2 saloon and the classic XJ6 handled. Period research was ripe with hazards, however, and his work included regular sessions at the Motor Industry Research Association test track.

Talking to Motor Sport (April 2013), Dewis recalled an incident when a C-type’s final drive seized as he came off the MIRA banking at full speed: “It cartwheeled onto the infield, coming to rest upside down on top of me with hot oil everywhere. A couple of labourers ran over and lifted the car. In the pub that evening I bought them all the Guinness they wanted.”

He survived all that – and worse – to remain a Jaguar ambassador into his late 90s.

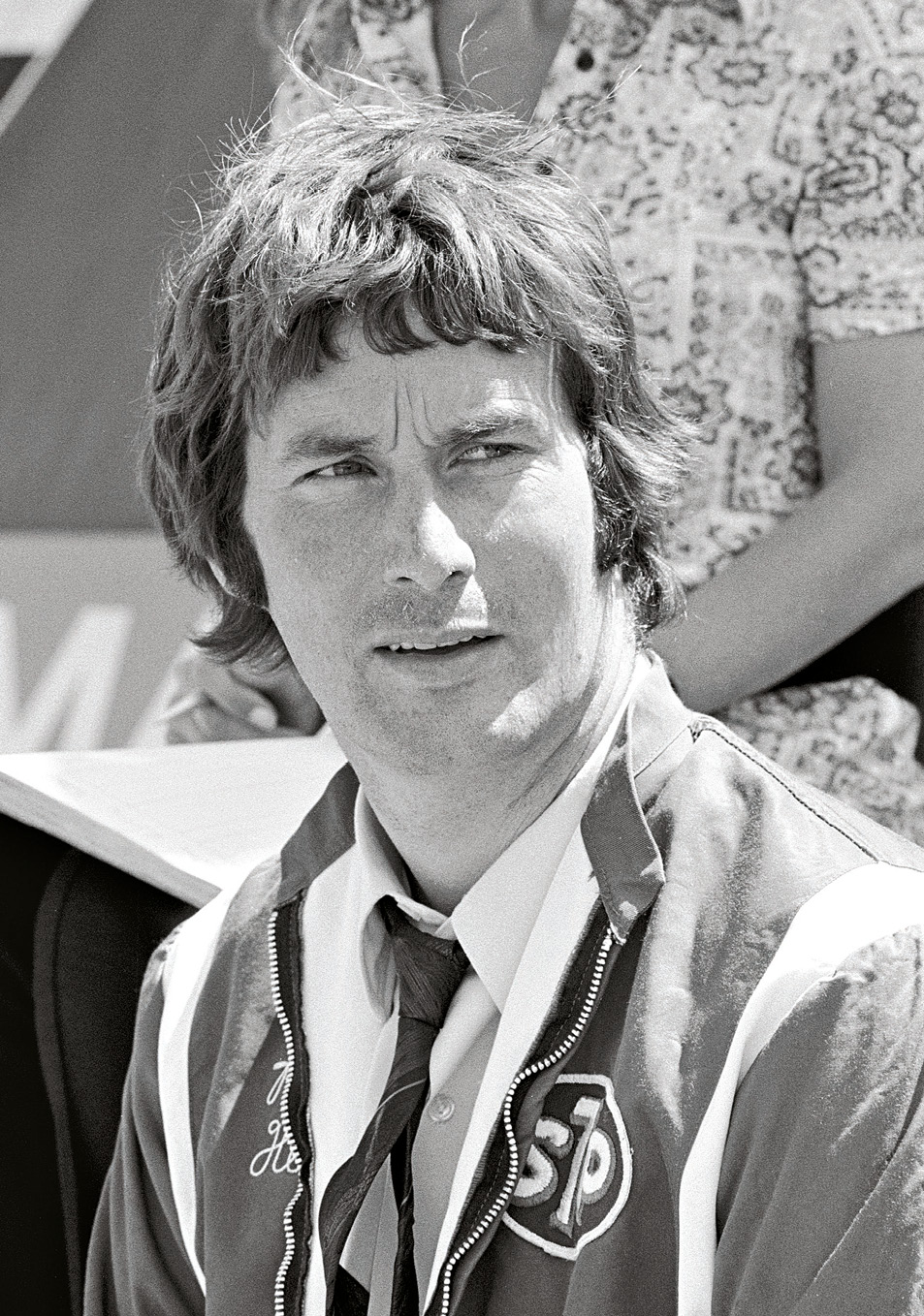

Robin Herd (left) could have become a professional cricketer with Worcestershire, but eschewed the offer in pursuit of higher education and achieved a double first in physics and engineering at Oxford.

Soon afterwards the future March co-founder joined McLaren and designed its first F1 car, the M2B, for which Herd chose Mallite – usually used in the aeronautical industry – in a quest for greater chassis stiffness. During testing in 1965, Herd also experimented with wings. Speaking to Motor Sport in 2010, he said: “The lads all took the mickey, telling me a racing car was meant to stay on the ground, not take off. But we made something up and ran it at Zandvoort. Instantly the car was three seconds a lap faster. We didn’t want anybody else to know, so took the wing home, sawed it in two and put it in the bin, saving the idea. It was more than two years later that Ferrari and Brabham came up with wings.”

Or this from early testing of the M6A, which defined the template for future Can-Am McLarens. “I worked out how we could run ground effect at the front. We tested at Goodwood with me stuffed into the passenger side, and an anemometer to measure pressure under the car. By the time we got to Madgwick the needle was off the gauge. Nobody realised we had a ground-effect car. We balanced it out with a big spoiler on the back…”

They don’t make engineers like they used to, nor indeed cars.