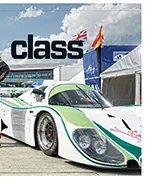

First-class second class

We asked versatile Frenchman Nicolas Minassian to try his hand at Group C2 – sports car racing’s finishing school when such as Porsche and Jaguar ruled the roost – and…

Sebastian Vettel’s outrage at having Canadian Grand Prix victory stolen from him – penalised for the manner of his rejoining the circuit after a brief off when battling with Lewis Hamilton – was understandable.

For 50-odd laps, the dominant two drivers of the previous decade had been engaged in an intense, all-out struggle, Vettel leading but under immense pressure, the speed advantage ebbing and flowing between them as each managed critical aspects of their complex cars. If he held on, this was going to be Ferrari’s first win of what’s been a hugely pressured season, this just adding an extra dimension. But that fascinating contest was neutralised by the obligation of the race stewards to apply a regulation because it’s there.

His reaction was classic Vettel: a switch-like fury that takes some time to subside, a raging against the injustice, only just barely managing to keep himself in check. A refusal to join in the parc ferme congratulations, stopping his car short and walking off. Then, slowly, coming back down from the roof and the ordinary, reasonable man beginning to resurface as he walked up there after all – but taking care to swap the number 1 and 2 bollards from the official result to the actual finishing order, with the Ferrari ahead. Sportingly, he shook hands with Hamilton. Up on the podium, as fans began to show their disapproval at what had happened by booing Hamilton, Vettel’s decency interjected once more, telling them to lay off, that it wasn’t Lewis’s fault.

He’s this interesting mix of emotional intensity and serenity, the competitor and the normal man. It’s like a trigger. An hour or so later, he was fine, merely sad and reflective. “Tomorrow, when I wake up, I won’t be disappointed. I think Lewis and myself share great respect and I think we’ve achieved so much in the sport, I think we’re both very, very blessed to be in that position. One win up, one win down, I don’t think it’s a game-changer if you’ve been around for such a long time.”

It’s more a question of regret that the sport – the world – has evolved in a way he finds regrettable. “I was just thinking that I really love my racing. I’m a purist, I love going back and looking at the old times, the old cars, the old drivers. It’s an honour when you have the chance to meet them and talk to them; they’re heroes. So I really love that – and I just wish I was maybe as good, doing what I do, but being in their time rather than today. That’s not about that decision today…”

“I love my racing. I’m a purist. I love going back to the old times”

The seasoning of all those years in the sport, the perspective it gives, is helping him right now to handle a very difficult situation, now into his fifth season with Ferrari but still without any titles to add to the four he got with Red Bull. For a man who has had the wonderful dream tantalisingly suggested by winter testing – becoming Ferrari’s first world champion in more than a decade – stolen by reality, he carries himself with remarkable lightness this year.

“I think I’m just realistic about the situation,” he said during the build-up to Monaco. “I’m not trying to hide anything… I can guarantee you that we’re not happy, we’re very pissed off. But I don’t think [carrying that] helps you in this situation. What helps is if you stay on course and be positive about the things you can control and not miss out on the gains you might make in the short term, as in this race or the next one.” Like winning at Montréal, one of the few circuits that might allow the Ferrari to compete on level terms…

He’s come to an acceptance that there’s no way back for this year’s car. Initially it was hoped that it was just a matter of unlocking it. “That’s what we were hoping with the upgrades we had coming into Barcelona,” he says with a wry smile. Whether it’s mischief, regret or explanation, the grin is always there. So is the sincerity. He’s interested and engaged once away from the spotlight. “But it’s now clear that it isn’t some silver bullet that’s going to switch the car back on,” he adds. “We’ve had more than one opportunity to do so, more than one test to understand at the same track what we might have been missing.

“We started off [in Barcelona winter testing] with a really, really good balance, but we’d lost that by Australia. That took some time to recover. We made progress, especially with the set-up, and therefore it was funny to return to Barcelona [for the grand prix]. The main difference from testing to the race was ambient and track temperature, quite a big and significant difference. We learned a lot along the way… If you come in and ask for more rear and more front and they can find a way of doing that, then you have to ask why you weren’t doing that before! So it’s only shifting around and trying to get a better balance. Because the amount of grip we have on the car is just what it is – you can’t just bolt on more. I think we’ve done well [getting the balance back], but it also became clear that even with a better balance three or four months later we’re just not competitive enough.”

It would be understandable at this point if the challenges of the situation – so long into his career, with so much success behind, the car proving so difficult, the rising status of thrusting young team-mate Charles Leclerc – were leading to thoughts of retirement. He’s quick to dismiss that. “I’m not at that stage yet. I’ve understood in the last couple of years that the end is less far from now than what I’ve put behind me. But I have no number to it. My prime target is to win and to prove this to myself and to ourselves that we can do this.” By ‘this’, the target is always to win a world title at Ferrari – which is the challenge that drew him here.

Yet this is the guy who, when asked recently what he thought his legacy might be when he did retire, fired back with: “I don’t know, I don’t care.” Did he really mean that? “Don’t get me wrong, I don’t want to sound too egoistic, but I do this for myself. I get a lot of pleasure out of it, I love what I do. I’m very ambitious. I want to achieve something with this team – and that’s my motivation. That’s my goal, that’s what I’m going after. I want to prove to myself that I can succeed.

“I love the sport and I am into its history – I’m just a fan. I know I’m driving the car so don’t need reminding of that, but I don’t wake up thinking ‘Wow, I’m an F1 driver.’ These numbers mean a lot to me. But to me. If there’s a legacy to leave I want to leave it for myself. Not what it might mean to other people. For me, for the team, the people that are around me. It’s not realistic that you’ll have everyone in this world on your side. I also understand that having the privilege of travelling, meeting so many different people from different places, seeing different cultures… In the end we are in a bubble. In the big picture, can you leave a legacy from what we’re doing? Probably not. But it means a lot to me.”

His current preoccupation is understanding global warming in fuller depth. But there are plenty of other preoccupations, such as his motorbike collection. Again, he’s old school in this enthusiasm. “I just like old things. Apart from the design, I can’t get much pleasure from new things. But ’70s bikes I can relate to. You can look at the bike and understand how it works, how things were designed for what purpose – sometimes funny but still… Whereas now everything is so perfect, there’s less character. I just ride them for pleasure, I don’t really go for performance. If you take my Kawasaki 750 for example, it’s more than 40 years old. I don’t think it was made for me testing it to its limits 40 years later. But having gone a bit fast on it, it’s a bit funny, let’s put it that way. I like motor sports, engines, the smell of petrol. With bikes, the same as with old cars but more so, you immediately see what you get. I like that and the feeling of riding a bike. You feel very free, there’s not much around you. Just to relax.”

He’d be a fantastic road trip companion.

But you wonder if the fact that he seems to feel things in a normal, human way, rather than as a hardened tough old pro, does sometimes undermine him, whether a susceptibility to pressure has played a part in key errors on track. “I don’t wake up in the morning thinking I am the number one,” he says, the toothy grin wider than ever. “I don’t look back saying, ‘I’ve won this before, I don’t need to win it again.’ I don’t feel like any success I had in the past grants me success in the future. Equally I’m very privileged. I’ve been in that situation more than once and proved to myself that I can beat the best and be among the best. I know you read a lot about this in motivational books or whatever, but for me the ‘I am the best, I am unbeatable’ doesn’t work. But I wake up knowing that I can be the best and I can beat the best. I get extreme pleasure out of that; that’s what I want to do and on top of that I want to do it here. It would mean something more to me, winning it with this team. I know so far I haven’t succeeded in the big picture.” It is what it is and if he does it, it will be as him. He knows we can only be who we are.

Against the expectation of many pre-season, this year he has taken leadership of the team despite the loss of Kimi Räikkönen as a support driver and his replacement by the ambitious, talented Leclerc. There are extenuating circumstances here and there, but as of Montréal Vettel had outqualified him 6-1. Not many would have bet on that before the season. He’s reluctant to comment too much on Leclerc, not because of any ill feeling but, “I don’t want to get boxed in by words… Yes, the atmosphere is different to how it was with Kimi. It would be stupid to say it wasn’t. Not just Charles, but his engineering team is a different one compared to last year as we’ve moved some things around. Also with Mattia [Binotto], he’s a different boss. It’s different and difficult to compare with before.”

Binotto’s style as team principal is hugely different to that of Maurizio Arrivabene’s; it is calmer, less confrontational, more supportive. It’s a vastly more suitable management style for Vettel’s traits as a bright, independent thinker, but it’s another area where, in public at least, he won’t be drawn. “You can see for yourself that he’s a different person… everybody’s different. But given where the team is in a different place this year competitively, you can’t really compare. I would say that given the situation as it is, and given how pissed off we are, things are still fairly calm.”

Fundamental re-evaluation of the technical concept behind this year’s car is clearly ongoing. But any rewards of that are unlikely to be seen before next year. Aside from being competitive aerodynamically, to see peak Vettel in action on a consistent basis will require it to be tuneable to his particular tastes, which are quite specific: a lot of rear stability into the corner to allow him to pitch it in aggressively, but then an agility that allows him to banish any understeer. “Yes, the car doesn’t need to be completely planted at the rear because I don’t like understeer. There are some drivers – it’s easier talking about ex-drivers – take David Coulthard, for example. He was one of the masters of understeer! I don’t know how you can go that fast with that much understeer: I just run out of solutions. There are drivers that get on with it. Maybe I’m less than that. I like a strong rear at a certain stage when entering the corner, but overall I prefer oversteer. It’s faster and you can do stuff.”

That inside the car stuff is, you sense, the only time Vettel truly loves current F1. “I don’t think things are maybe as good as they used to be in terms of the sport and the cars. But then I’m not making the rules and I don’t think it’s easy to find rules that suit everybody. Call it politics, call it whatever you want. Also these days certain things have become so professional, so perfect in a way, but I think that’s not just valid for F1 but is valid for all the sports. It’s impossible to un-know something. Even if you think it was better because we didn’t know stuff, you can’t go back to that, it’s impossible.”

Rooted in the past, but still with a future. Furious in the moment, yet serene in reflection.