Dennis severs all ties with F1 team ahead of hearing

Just before the Chinese Grand Prix Ron Dennis announced that he is to completely relinquish his involvement in Formula 1 to focus on running the newly-created McLaren Automotive, which is…

Last August the Bonneville Salt Flats played host to something truly extraordinary. Some of the most pioneering, innovative and even bizarre automotive creations in history have featured at Bonneville over the years, but perhaps none has managed to hit the sort of emotional heights that Challenger II did, with a Thompson at the wheel again.

This time, however, it was Danny Thompson in the driving seat, out to make up for lost time and finish the journey his late father, Mickey Thompson, embarked upon over

50 years ago.

They called Mickey Thompson ‘The Speed King’ for good reason. The colourful Californian hot-rodder set more than 500 speed records over his lifetime, and if Thompson drove it, he also probably had a hand in designing, building and promoting it.

From Indianapolis to Pomona, by way of Bonneville and Baja, Thompson’s name was synonymous with speed and performance over the course of nearly four decades. Even now, 30 years after he and his wife were brutally murdered on the driveway of their suburban Los Angeles home, Mickey Thompson remains a titanic figure in the history of American motor sport.

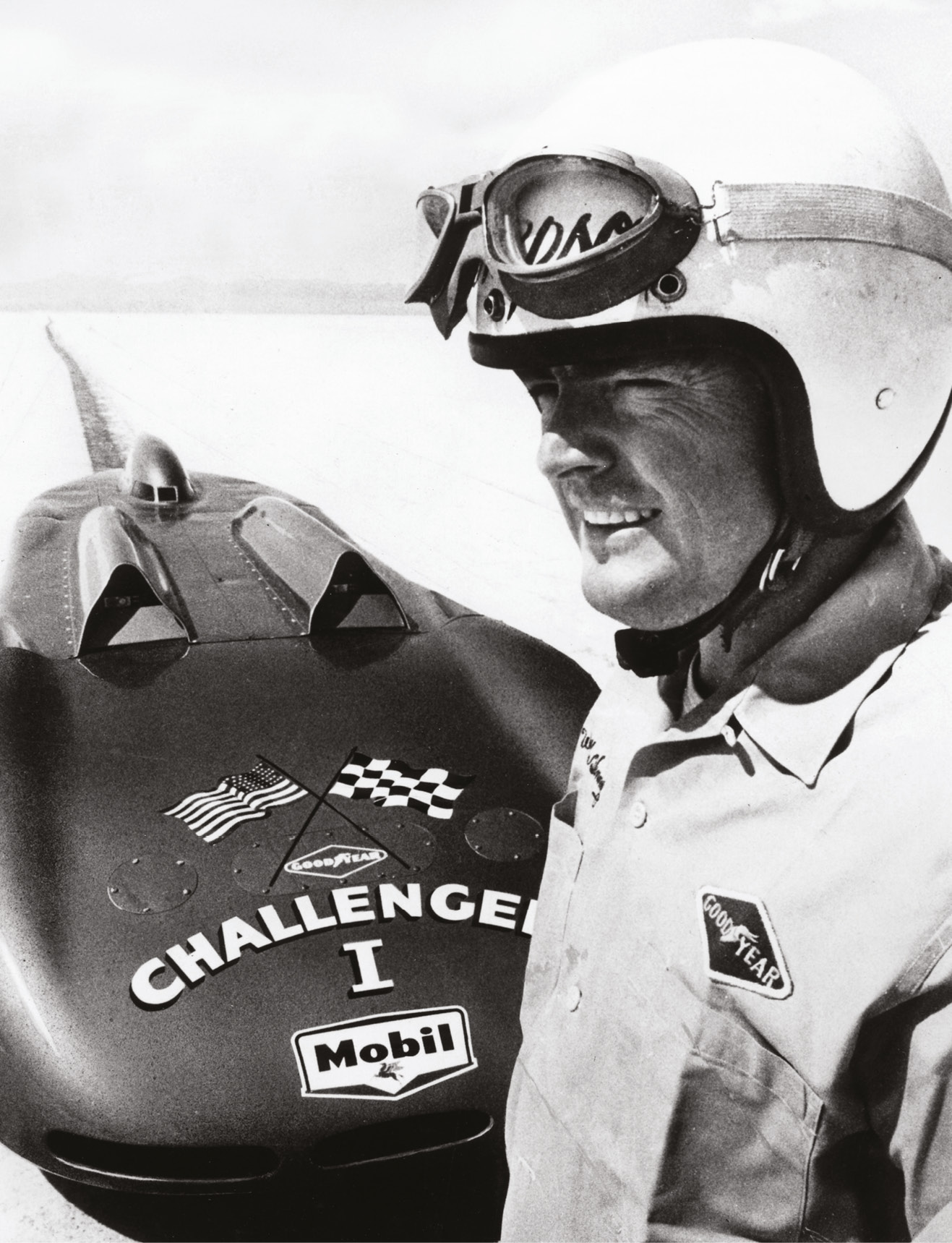

Thompson was mesmerised by Bonneville since 1950, when he made his first high-speed run at the famous salt flats, a salt-crusted dry lake bed spanning 40 square miles in western Utah. Ten years later, he became the first American to surpass 400 miles per hour in a piston-powered vehicle, clocking 406.60mph in the innovative Challenger I. But he didn’t set a record because the car broke one of its four supercharged Pontiac engines and failed to complete the opposite direction run required by the Southern California Timing Association (SCTA) for certification.

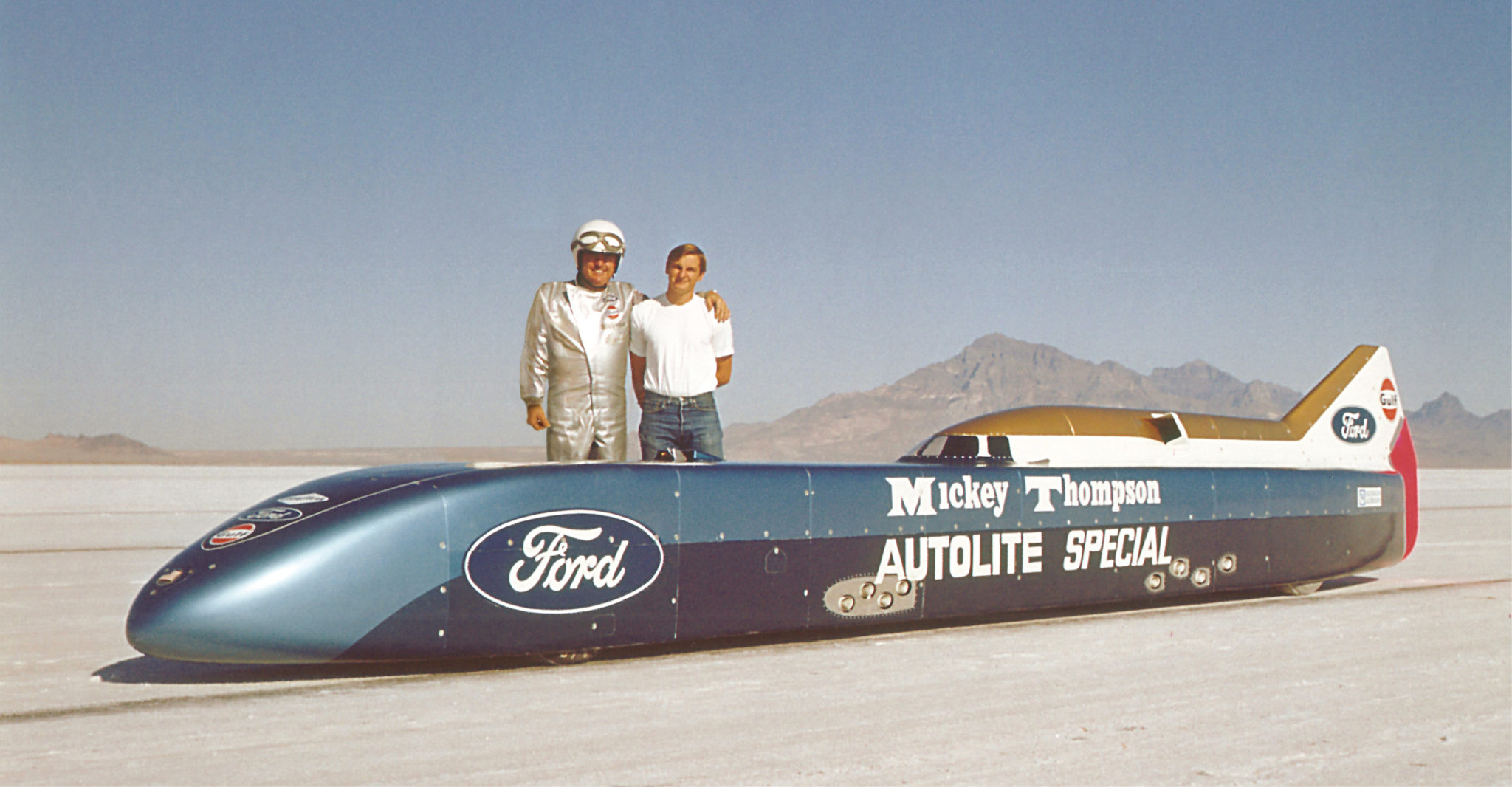

Thompson returned to Bonneville in 1968 with Challenger II, liveried as the Autolite Special. This was an even more radical streamliner designed by Kar-Kraft and built by Mickey Thompson Advanced Engineering, now featuring a pair of single-overhead-cam 427 cubic inch Ford V8s for motivation. The car tested fast, but rain washed out a scheduled FIA-sanctioned attempt and, by the time the salt was ready for action in 1969, Challenger II was parked due to loss of sponsorship.

Thompson focused on his business interests in the 1970s and ’80s, most notably forming SCORE International (Southern California Off Road Enthusiasts) to sanction off-road competition and inventing the modern concept of stadium racing. But as the 20-year anniversary of his last Bonneville appearance approached, he hatched a plan to return to the Salt Flats with Challenger II, this time with his son, Danny – by then a successful racer in his own right – doing the driving. Remarkably, the same record Mickey was chasing in 1968 (409.277mph achieved in 1965 by the Summers brothers in a streamliner called ‘Goldenrod’) remained unbroken. Challenger II was taken out of storage in January 1988, but Mickey Thompson was killed before any significant work was done.

He and his second wife, Trudy, were shot dead by two hooded gunmen on bicycles early on the morning of Monday, March 16, 1988 as they attempted to make their way to work. While the hired assassins were never caught, one of Thompson’s former business partners, Michael Goodwin, was arrested some 13 years later in connection with ordering the hit after losing a $514,000 judgment to Thompson, forcing him into bankruptcy. Goodwin is currently serving two life sentences without parole.

“30 years after the brutal murder, Thompson remains a huge name”

For Danny, the loss of his father and step-mother was a crushing blow, because the common goal of taking care of unfinished family business at Bonneville marked a significant rapprochement for father and son.

“That was a huge step for my dad and me,” Danny says. “We got along so well, but my dad wouldn’t let me race. He didn’t want me to get hurt; he’d seen so many people get killed over the years in the 1950s and ’60s before the safety effort really started marching forward. I did some racing, had some success, won some championships, but all on my own. So, when he called me and asked if I would come drive Challenger II, it was pretty amazing.”

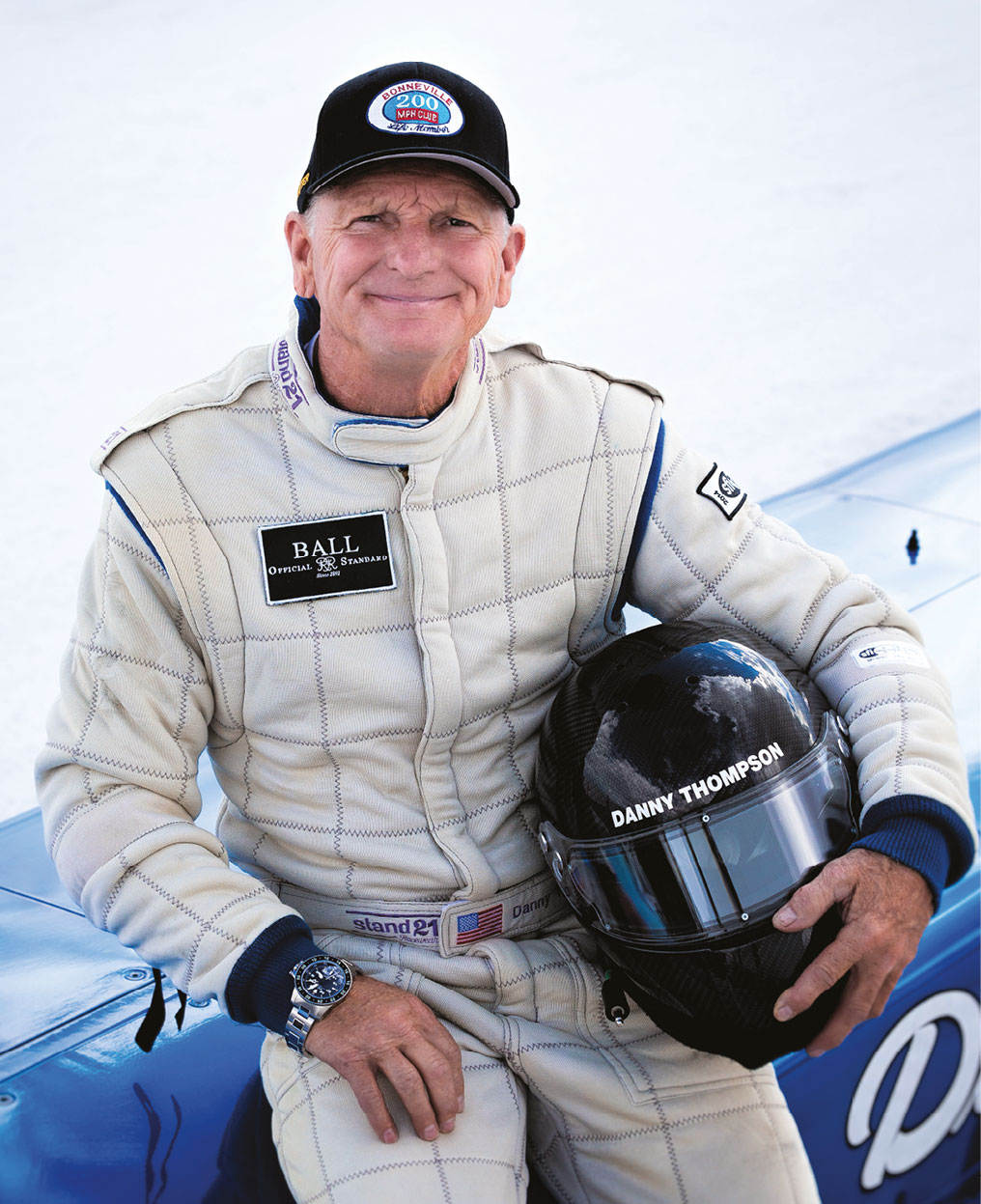

Mickey’s death was tough on his son, and 30 years later, Danny still gets emotional when he talks about his father. Danny didn’t return to Bonneville until 2003, when he was invited to make an exhibition run in another car that Mickey formerly owned. Danny had retired as a circuit racer in 1995, but found himself drawn back annually to the salt flats by his father’s legacy and the uniquely intense, yet laid-back form of competition he found there.

In 2010, Danny’s focus on Bonneville became much more personal. “Somebody posted something about the 50th anniversary of my dad’s 400mph run, and I said to my wife, ‘I wonder if I can do that? What if I could go 400mph in that car?” Thompson recalls. “That thought started the wheels in motion. I’d been thinking about it for years, but not seriously enough to attack it. I didn’t want to be sitting on my couch when I’m 80 years old wondering if I could.” He was 61 at the time.

Inspired by the milestone date and encouraged by his wife, Valerie, Thompson pulled Challenger II out of storage and began the process of updating it for a new attempt at the piston-powered record of 417.020mph (subsequently upped to 439.562mph by George Poteet in 2012). He set up a new shop in Huntington Beach, California, about 15 miles from Mickey’s old workshop in Long Beach where the car had originally been constructed, and got started on what proved to be a lengthy and laborious task.

“I didn’t want to be sitting about when I’m 80 wondering if I could”

The car is a huge dart-shaped object, some 32 feet long, 36 inches wide and 28 inches high, excluding the tall rear fin, and weighing 5700 pounds when fuelled. Danny wanted to keep as many elements as original as possible to honour his father’s vision, while incorporating modern safety improvements where practical. The chassis was essentially unchanged and the wheelbase remained the same, but project engineer Tim Gibson (ex-Boeing and National Hot Rod Association) lengthened the bodywork by 32 inches to create separation between the centre of pressure and the centre of gravity to stabilise the car in yaw. The front and rear drive axles carried over, but instead of a separate throttle control for each engine, they were linked by a novel three-piece driveshaft.

Naturally, there was more power – some 5000 horsepower, almost triple what Mickey had in the 1960s – achieved by swapping the original 427 Fords for a pair of nitromethane-fuelled Chrysler Hemi engines driving through modified three-speed B&J drag-racing transmissions. Steering and braking systems were totally redesigned around newly fabricated uprights. Outside of a digital dash, there were no modern amenities like traction control, although Danny stressed that had he started from scratch rather than from a 50-year old base, he would have done many things differently.

“My dad got the best California drag racing guys of that era to come to Long Beach to build that car – Nye Frank and Tom Jobe and Bob Skinner and Pat Foster – and they got it done in six months,” Thompson reflects. “I thought in a year, we’d get the car done, take it up to Bonneville and go fast. Well, it took eight years. It was for sure the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life but definitely the coolest.

“Mickey’s guys are my heroes and all the names of the main original crew are on the car as well as the names of my guys. The car never got proven and I wanted to give them some credit.”

Thompson actually got Challenger II up and running in 2014. Speed Week was cancelled due to weather, but he clocked 390.471mph a few weeks later at the Bonneville ‘World of Speed’ event in the car’s first full pass since 1968. Danny pushed that number up to 419.702mph the next day, but the car broke a clutch on the return run.

The track was washed out again for Speed Week in 2015, giving Thompson and his team ample time to fine-tune the car for another attack in 2016. That attempt proved somewhat more successful, as Danny completed a two-way run in poor conditions, averaging 406.769mph to barely exceed the speed his father ran in 1968. “A tenth of a mile an hour in 48 years,” scoffs Thompson. “The salt was so rough that when I went by the three-mile sign, I couldn’t read a four-foot by four-foot fluorescent banner, it was beating me that hard. It was like running the Baja 1000 at 400mph.”

The salt surface improved in 2017, and so did Challenger II’s speed. Thompson had Poteet’s record in sight when he reached 435.735mph on the outbound pass, but the car suffered a DNF on the return when no fewer than six connecting rods snapped. “We installed 16 new rods, got it on the trailer, and then it rained,” Thompson says. “The [rod] supplier told us, ‘You’re in uncharted territory. Nobody has ever run these things that hard for that long,’ he said. “That was a big learning curve. We had lots of questions, but nobody had answers. It cost us a lot of money and another year. But that’s the thing about Bonneville – you only get to run a couple events each year.”

In 2018, everything went to plan. With Challenger II tuned up and benefiting from salt conditions more conducive to speed, Thompson clocked 446.605mph on his outbound pass. The car was then impounded for 24 hours per Southern California Timing Association rules before being fuelled and prepped for a record-clinching return run at 450.909mph to establish a new Unblown Fuel Streamliner (AA/FS) class benchmark average of 448.757mph.

“We added three per cent more nitro, which was probably worth around 700-800bhp extra”

The five-mile timed pass lasted barely a minute and it looked like a smooth ride, but in-car video footage tells a different story. If you ever want to see what opposite lock looks like inside a 32-foot ground missile, seek the footage out on YouTube or the Thompson LSR website.

“It got a little squirrely,” Thompson admits. “[Engine tuner] Richard Catton added three per cent more nitro, which doesn’t sound like much, but with what we were running, was probably worth 700-800 horsepower. The thing accelerated so hard, up until third gear. When we shifted, the thing went sideways and she spun the tyres from the third mile to the fifth mile. But it came back and we legged it on through there.”

Even without Mickey, Danny’s record was very much a Thompson family affair. His wife Valerie served as team manager (“the backbone of the operation,” according to Danny), and she, along with his mother – Mickey’s first wife, Judy – and son greeted him in the cooldown area after he brought Challenger II to a stop.

“When you work this hard for this long and have that kind of result, it just puts a magical star above the whole project,” Thompson says. “It’s pretty darn cool just to finish the family business, because my dad never officially got that record. It took 50 years, a lot of elbow grease and a few modifications, but I feel like I was finally able to fulfil his dream as well as my own.”

Finishing the pursuit of the record his father set out to break brought Danny a mixture of joy and relief. But the eight-year process was physically exhausting and financially devastating. Without the benefit of a lead sponsor, Thompson depleted his own savings and eventually resorted to crowdfunding for support. His crew consisted of unpaid volunteers. The name of every individual who contributed to the Challenger II effort was displayed on a banner that Thompson and his crew posed with after the record-setting run.

“It took 50 years, but I finally feel like I was able to fulfil my dad’s dream as well as mine”

“We had lots of donations from groups of people and that was hard for me because I felt it was begging,” he says. “I’m kind of a proud bastard. But in the end, whether they contributed $1 or $5000, the people are what made it happen. My crew worked non-stop, and these are all volunteer people. None of them were paid and they did it because they were passionate about the project.”

Thompson is convinced that with development Challenger II could top 500 miles per hour at Bonneville. But that’s not going to happen, because the car is being retired while it’s still on top. He’s talked to several notable collections about displaying the historic machine, including The Henry Ford, the Smithsonian Institution, and the Petersen Automotive Museum.

“It’s 50 years old, and it went out and did its job. I can’t just keep running it,” Thompson adds. “I might be leaving some speed on the table, but I’m 69 years old and I’m walking away – which might not be the case if I go for another 430mph lock-to-lock joyride. Financially, it’s crippling, and without a big sponsor it’s just not possible. I’m trying to figure out where to put it and I’m going through different options.

“Whatever I do, I’m going to get Challenger I and Challenger II to sit side by side. I think that would be quite a tribute to the whole project – although if I could find funding, I would love to build a new car…”