Veteran to Classic. . . . . Lost Giant

Lost Giant A contemporary (I must not mention names, but I respect Mike McCarthy for running a slick ship!) published a story recently that has a ring of mystery about…

For all its sumptuous history, Alfa Romeo’s premier-league competition image was fading by the mid-Sixties – submerged beneath time’s passage. A little prestige was occasionally restored in the saloon and small-capacity GT classes, but top-level racing was almost Alfa-free.

One who had moved to mitigate this problem was Dr Orazio Satta Puliga, the Milanese company’s design director since 1946. He had remained keen on racing, despite financial constraints having forced the nationalised firm to quit Grand Prix racing at the end of 1951. Alfa Romeo had never been a large-scale motor manufacturer. Its 1951 production totalled only 1277 4C-1900s and 55 6C-2500s. Subsequently, following introduction of the Giulietta in 1955, output boomed. Through the mid-1960s production hit nearly 50,000 per year, and Alfa’s board began thinking seriously about a serious return to major-league racing with a purpose-built sports-prototype.

Designer Giuseppe Busso – one of Satta’s two deputies – had spent a brief period as Ferrari’s chief engineer at the dawn of the Maranello marque, 1947-48. A rather earnest, steady character, he was effectively bullied out of Ferrari – and back to Alfa Romeo – by the domineering personalities of Enzo Ferrari and new engineer Aurelio Lampredi. Busso fitted in better at Alfa. His work alongside Satta had included a two-litre V8 intended for a stillborn GT project.

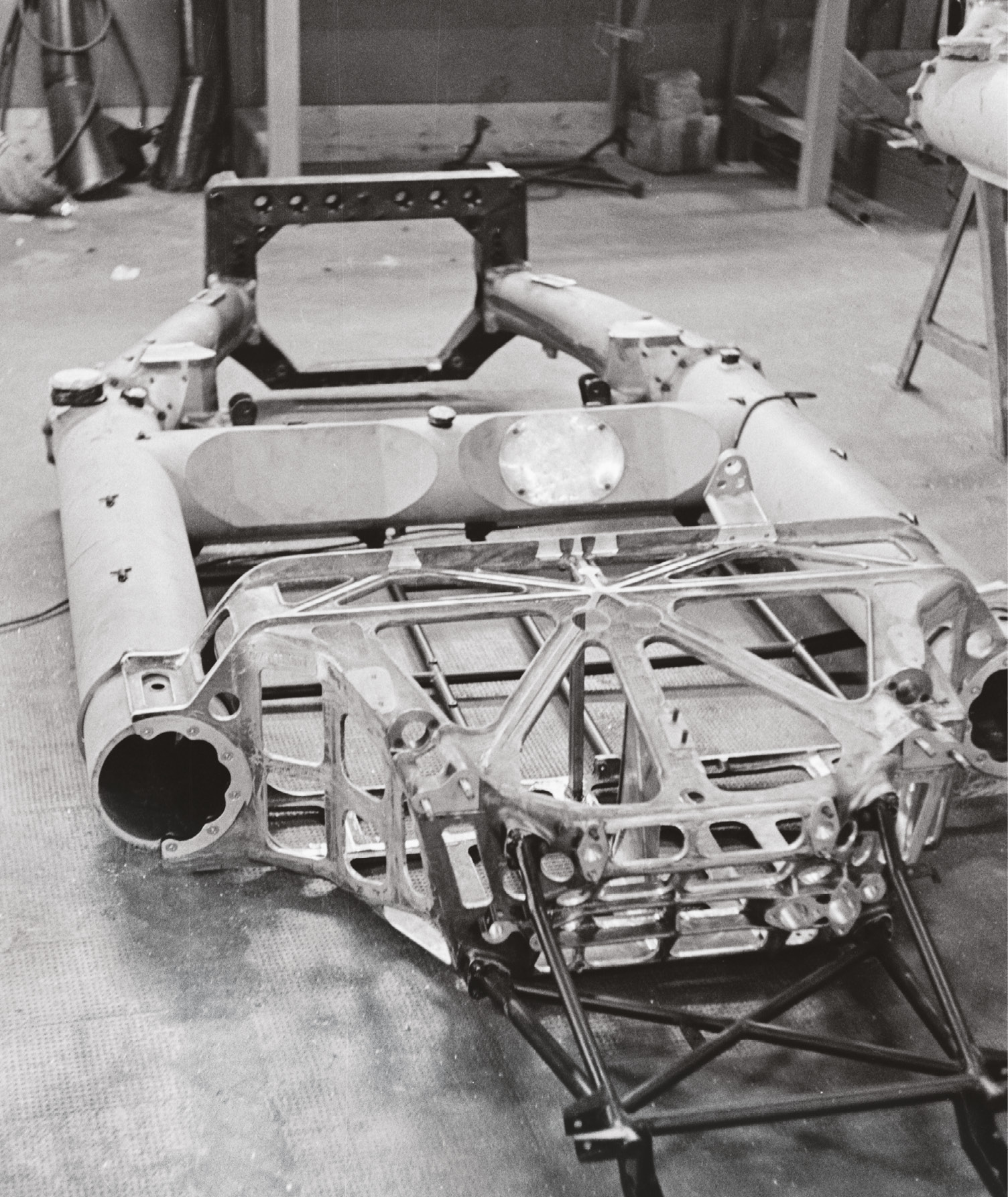

When Satta found support for racing from Alfa’s new president Dr Giuseppe Luraghi, the firm adopted a new kind of chassis construction for what emerged in 1966-67 as the Alfa Romeo Tipo 33. Busso’s team detailed an advanced yet simple structure using just three large-diameter tubes united by a third forming a virtual H in plan. In 1967 these tubes – formed by Aeronautica Sicula – were in heavy-gauge aluminium, riveted together and coated internally with plastic to carry 26 gallons of fuel. For 1968 light-gauge titanium tubes, formed by rolling and welding, would replace the aluminium, while a suitably H-shaped Pirelli bag tank held the fuel.

Alfa Romeo had wide experience of machining large-scale castings for the aeronautical industry – many in lightweight magnesium-alloy. Now the front end of the big-tube H-form chassis was mated with a complex magnesium casting by Campagnolo of Vicenza – initially solid, but later a lightened lattice-pattern – which linked the side tubes and formed the scuttle and footbox. Its front face carried sheet-steel fabrications providing the front suspension pick-ups. It also carried the steering rack, front anti-roll bar and the brake and clutch master cylinders. Attached supports carried the nose body section and radiator.

The rear of each big-tube side member was bolted to cast-magnesium horns, which then tapered rearwards (and curved inwards) to provide V8 engine mounts. These horns were then united laterally by a sheet-steel ring bulkhead that picked up the rear suspension links and carried the new six-speed gearbox on a rubber bush. A large strut-braced tubular-steel roll-over bar carried forward rear suspension pick-ups, while a simple tubular frame extended behind the rear bulkhead to carry the tail body section and – on the right-hand side – a large dry-sump oil tank, most of whose mass was supported by a tapered-tube extension of the right-side engine-bay horn.

Carlo Chiti, the roly-poly former Ferrari chief engineer from 1958 to ’61, who had masterminded the ‘Sharknose’ cars which had won the F1 World Championship, was an ex-Alfa employee who was fired by Mr Ferrari late in that otherwise successful year. He had then been engaged to produce the rival Serenissima F1 and GT cars that emerged in 1963 as the ATS V8s – a programme that had collapsed by ’64.

During his early stint with Alfa, Chiti had worked under Satta and Busso with Giotto Bizzarrini and Lodovico Chizzola. All three had then joined Ferrari. Chizzola then left shortly before Chiti was fired and set up his own new motor sport preparation shop, while also developing an Innocenti dealership in Udine.

Luraghi of Alfa wanted to create a dedicated technical unit specialising in competition tuning and development, as a quasi-works operation. Luraghi had initially approached Chiti to see if ATS could be interested, but that venture was too new at the time, so Chiti approached Chizzola and they formed a partnership to meet Alfa’s new needs, eventually to be entitled Autodelta. In effect Autodelta would become Alfa Romeo’s post-war equivalent of the pre-war Scuderia Ferrari – the quasi-works operation Luraghi had envisaged.

Initially Autodelta had to produce 100 Alfa Romeo TZs to achieve FIA homologation for GT racing. That went well, so soon Autodelta became an Alfa Romeo division and its base moved from Udine to Settimo Milanese, closer to the parent plant at Il Portello. While Autodelta built a good reputation with customers for its TZs and touring cars, it would also construct and campaign the new T33 sports-prototypes.

That new project’s engine was a two-litre four-cam V8, and – inevitably with Chiti’s involvement in Autodelta – many assumed that it was an evolution of his two-year-old ATS F1 and GT V8. That wasn’t the case, for it derived instead from the Satta/Busso/in-house Alfa unit mentioned above.

It was a 90-degree V8 with chain-driven twin-overhead camshafts per cylinder bank, hemispherical combustion chambers, an 11:1 compression ratio and two valves per cylinder. Bore and stroke were 78mm x 52.2mm, 1995cc. A flat-plane crankshaft was used, eliminating the need for crossover exhaust pipes between the cylinder banks, and forged titanium con-rods featured. Ignition was by two spark plugs per cylinder, but a four-valve, single-plug, head was on the way. A slide-throttle system was used, with fuel injection – and a parallel 2.5-litre unit was under development, for 1968… Claimed power was 256bhp at 9000rpm.

“The brakes failed, it hit an open trackside drain cover, flipped and caught fire”

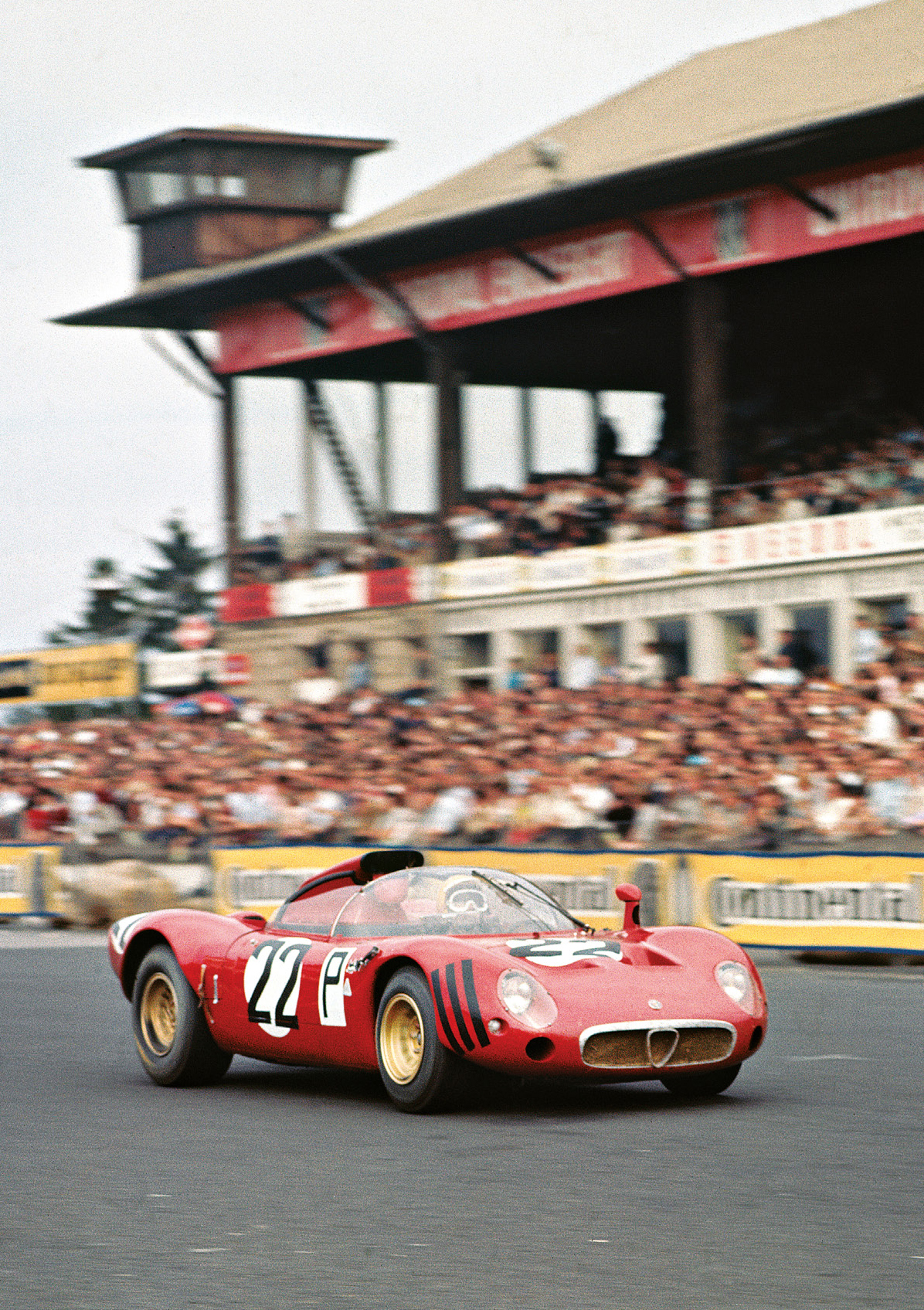

The original Alfa T33’s body was in glassfibre, with clamshell-opening nose and tail panels and a tall engine airbox rising from the recessed rear deck to earned the initial 1967 model the nickname of T33 ‘Periscopica’.

On January 7, 1967, the first car was demonstrated to the Alfa Romeo board behind closed gates at a chilly Monza. Tester Teodoro Zeccoli drove, but the car’s brakes failed, it hit an open trackside drain cover, flipped – and caught fire. Magnesium burns particularly well, but Zeccoli was lucky to escape quite lightly. Both he and fellow tester Nanni Galli would recall the early T33’s handling as terrible, the front end wandering unpredictably, possibly due to flex in that complex magnesium front bulkhead. Geometry improvements were made, however, and in the T33’s low-profile debut at the Belgian Fléron hillclimb in March ’67, Zeccoli set FTD.

Two Autodelta T33s were then rushed to the Sebring 12 Hours, outqualifying the rival Porsche 906s and Dinos before the underdeveloped cars faltered. Three T33s all failed at the Targa Florio, but on May 25 at the Nürburgring 1000Kms the Zeccoli/Businello entry finished fifth. Second and fourth places followed at the Rossfeld mountain climb, then in June Galli won the Monte Pellegrino climb in Sicily. “Big deal,” said some.

Jean Rolland won his class at the Chamrousse hillclimb in France, before the final outing of the year – in the Ettore Bettoja Trophy at Vallelunga, Rome, heralded the first race finishes for de Adamich and Galli, first and second for Autodelta and Alfa.

The Alfa T33 family endured lengthy and somewhat tortured development. Count Rudi van der Straten’s Belgian Team VDS became the model’s first major customer, Teddy Pilette winning the 1968 Coupe Benelux race at Zandvoort, before Lucien Bianchi/Nino Vaccarella/Nanni Galli won at Mugello in July 1968, while Vaccarella/Zeccoli won the Imola 500Kms in September.

The T33’s original-style ‘big-tube’ H-form chassis was abandoned for 1969 and a new 3-litre T33/3 emerged, with a conventional dural-skinned monocoque and 400bhp-plus at 9000rpm. By 1970, Piers Courage/Andrea de Adamich would win the Buenos Aires 200, and into 1971 de Adamich and Henri Pescarolo won the BOAC 1000Kms at Brands Hatch, Vaccarella/Toine Hezemans the Targa Florio and de Adamich/Ronnie Peterson the Watkins Glen Six Hours.

Here – at long last – was the major-league success of which Satta, Busso and Luraghi had long dreamed. But it had taken a terribly long time for the T33s to get there… and by the time they did, the T33 was a quite different animal from the ‘Periscopica’ prototypes of several years earlier.