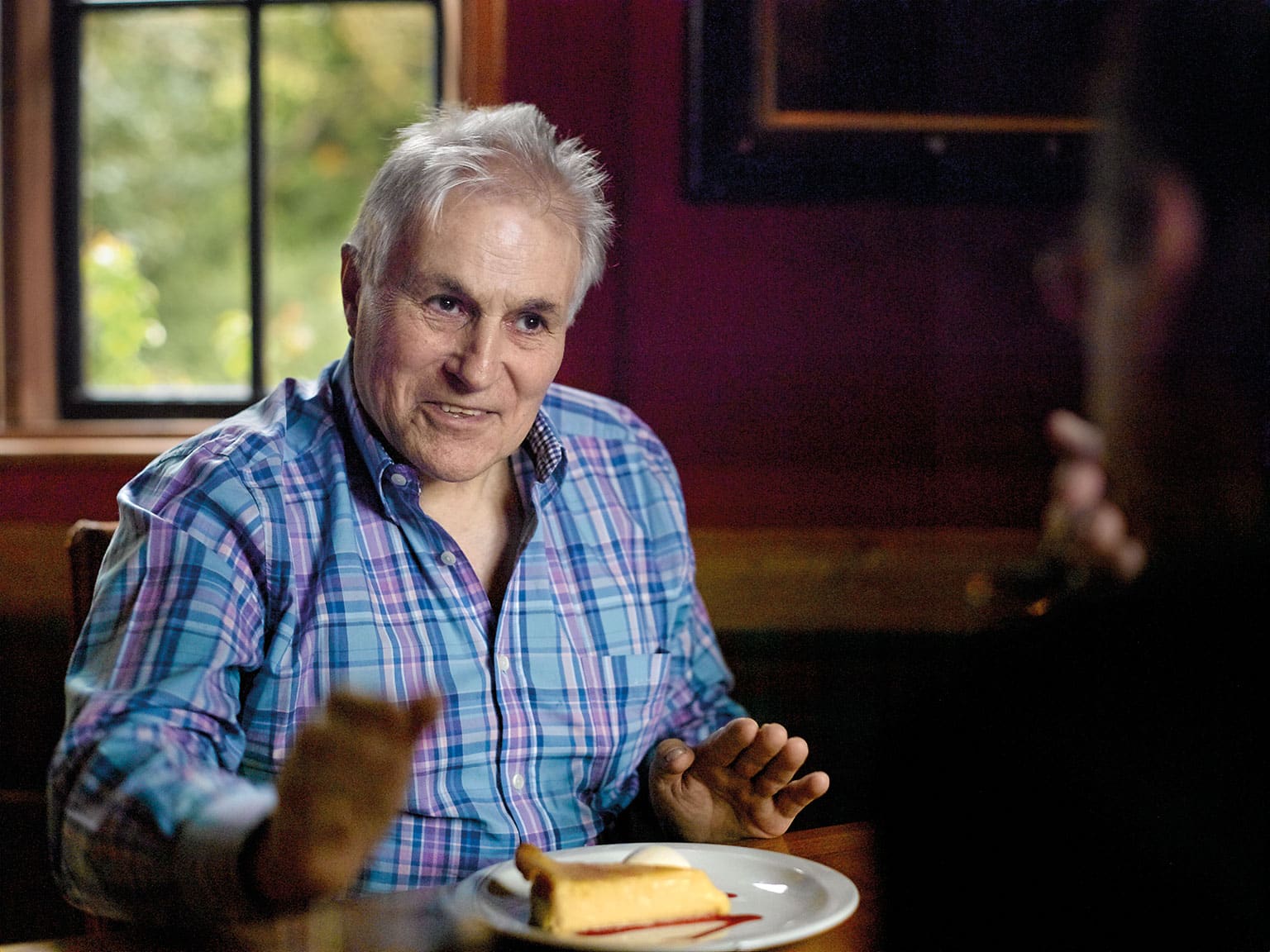

Lunch with... David Brodie

For much of his 50 years in British racing he was a serial winner, and he rubbed shoulders with the Formula 1 crowd as well

James Mitchell

As we know, Formula 1 has pretty much taken over the motor sporting world. It gets almost all of the media coverage, almost all of the money and virtually all of the glory.

A whole new generation of people who think of themselves as motor racing fans – even though their only sight of racing comes through a television set – don’t seem to understand that F1, impressive and exciting though it may be, is only one part of motor sport, involving just 22 drivers on 19 weekends of the year.

They don’t realise that there is so much more wonderful stuff going on, from endurance racing to rallying, from touring cars to historics, from true club racing to hill climbing, autocross and trials. In most cases they can’t watch it on TV, but what they can do is go and watch it in real life, and get involved in the experience. And, if they’ve got a remotely suitable set of wheels, they can even put on a helmet and take part.

Apart from those 22 F1 superheroes with their multi-million dollar deals, and a worthy array of professional racers making a good living in other forms of international racing, there are literally tens of thousands of competition licence holders who pursue their hobby on a shoestring, coming home from a hard day’s work to prepare their cars far into the night, and then setting off at dawn with battered tow car and trailer for a weekend’s excitement and fun. Sometimes they may have considerable ability; more often they probably haven’t. But in any case they too are racing drivers, and they are the true backbone of motor sport.

Over more than three decades I served my time covering Formula 1, and feel very privileged to have done so. But I have also spent nearly 50 years following, writing about, talking about and occasionally ineptly participating in the lower levels of motor sport. In all that time it is not the actual races, not the cars, but the people I remember best: a motley mix of drivers fast and slow, rich and poor, optimistic and downcast, united only in the desire to beat their rivals in wheel-to-wheel battle. As today’s F1 stars become ever less approachable and – it might be argued – less interesting as people, it is the unforgettable characters in British motor racing that I remember most fondly. Which is why, this month, I decided to have lunch with David Brodie.

Early days at Silverstone in the Austin A30

Motorsport Images

Brode, as he is universally known to his countless friends if not to his enemies, is certainly an unforgettable character. Last year he celebrated his 50th season in the sport. He always set about his racing with great professionalism, a lot of talent, and a burning will to win. And he had a remarkable degree of success. If you believe his own statistics he is probably, in terms of number of wins, one of the most successful British racers of all time. Going through the records myself I find that, at one stage of his career, he scored 40 outright victories on British circuits over a period of just 18 months. He held lap records on almost every track he visited, some of which stood for many seasons. Cocky, determined and always up for a laugh, he invariably spoke his mind, both before and after a battle, and often in terms that would make a sailor blush.

His contacts in motor racing stretched far beyond the British events in which he starred. He was an early director of Williams Grand Prix Engineering, and was Frank’s saviour when the team was beset by early financial problems. He is still close to Frank, and is Claire Williams’s godfather. He seems to have known everybody in racing at every level: he was best man at Ronnie Peterson’s wedding, and Ronnie was best man at his. He was a leading light in the Springfield Boys’ Club, which brought him close to Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart, and served as a director of the BRDC.

All this time he was working up to 80 hours a week at his day job, a very successful electro-plating business. Later sources of income to pay for his racing included a patented invention for lighting suspended ceilings in offices, and a string of antique shops. There were frequent brushes with the law, because Brode regarded getting from A to B on the public road as a challenge and did not always behave himself – although he laughs to scorn the rumours that he was involved in the Great Train Robbery, fanned when he befriended Roy James while Roy was in prison.

He’s 71 now, and I’ve known him for 45 years. He was always incredibly fit – never smoked, never drank, and was a relentless runner, usually fitting in a few early-morning laps of each circuit before practice. A couple of years ago he was diagnosed with bone marrow cancer, and courageously withstood a string of ferocious and debilitating treatments. He’s now recovering well, back to exercising every day, and when we met he was preparing to ride his bike the 87-mile length of the Kennett Canal from Reading to Bristol.

1.3 Ford Anglia was an effective race winner

Motorsport Images

His choice of lunch venue is a rustic inn, the Crooked Billet at Stoke Row, near Henley, where the food is far better than pub grub has any right to be and there are rotting classic cars outside. Dave maintains that he is a vegetarian, and then chooses chicken liver pate, tender roast duck, and lemon tart with mango sorbet, plus gallons of sparkling water.

He was born during World War II in Harrow. When he was four and his sister Susan was two, his mother went off with another man, known as Uncle Phil. But his father did an excellent job of being a single parent – this was in the 1950s, when such arrangements were rarer than they are now – and Brode adored him. “We’d always eat breakfast together, and after school Susan and I would clean the house. I had a very happy childhood.” In 1951 Dad took eight-year-old David to the British Grand Prix at Silverstone. He was mesmerised, particularly by the green Thinwall Special Ferrari driven by Peter Whitehead, and that day a seed was sown.

Brodie Snr had a thriving electro-plating business, a large house and a Bentley – until something went wrong, the money melted away, and house and business went, to be replaced by a semi and a leaky shed for the plating in Feltham. Meanwhile David, already a tearaway, was expelled from his private school and ended up at the local state school where, small of stature, he learned to use his fists to ward off bullies. A forgetful American serviceman living nearby made a habit of parking his black and yellow Studebaker with the keys in the ignition. “My mates and I, all 13 or 14, would wait until the lights went off in his flat, then six of us would cram into the car and drive flat out up to the Busy Bee café on the Watford Bypass, with Radio Luxemburg playing Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and Frankie Lymon. We’d have ham, eggs, chips, HP sauce, mugs of tea and thick bread and butter, and by 3am we’d have parked the car neatly where we’d found it and be tucked up in bed.”

Brode was never scared of hard work. He had a Saturday job in a greengrocer’s and a paper round, and cleaned neighbours’ cars. At 16 he left school and told his father he wanted to go into the electro-plating business, ignoring warnings that it was a hard, dirty, smelly job. His ambition was to help his Dad earn back his big factory and his Bentley. After learning his craft in a couple of firms he joined his father in the Feltham shed in his late teens. But then suddenly Brode’s father, still in his mid-50s, died. Brode and his sister were devastated. To cheer her up, Brode found her an old Triumph Spitfire and told her to go off with a girlfriend on a motoring holiday in France. On one of the autoroutes the Spitfire was involved in an accident and Susan was killed.

Alone now, Brode dealt with his grief by flinging himself into work, and into motor racing. Already a keen spectator with his mates at Brands Hatch and Snetterton, he decided his four-door Austin A30 could make a race car. He built up an 1100cc engine for it, somehow making four Amal carburettors breathe through a two-port head: even then he was looking for extra tweaks to beat the opposition.

He painted a stripe down the bonnet, removed grille and bumpers, and set off for the Eight Clubs Silverstone. His first outing was a five-lap handicap, and he won it. Next came a scratch race, in which he finished third behind an Austin-Healey 100/4 and a hot Mini-Cooper. It was enough to convince him that motor racing was for doing, not watching.

Lotus Elan shared Run Baby Run colours

Motorsport Images

Then, for various bits of lunacy, he lost his road licence for three years, reduced to two under appeal. Undaunted, he fiddled a competition licence in a friend’s name and started racing a Turner sports car, but did the friend’s reputation no good by rolling it at the Snetterton hairpin. During the week he found himself chroming wishbones and radius arms for several local racing teams, and one customer was F3 racer Frank Williams.

“Frank had been campaigning a very quick Austin A40 which wore the fictitious number plate FU2, until race officials told him to remove it. But he had his sights set on higher things, and sold the A40 to Jonathan Williams’ F3 mechanic, a young guy called Chris Airey. Chris turned out to be hugely talented, and it was terrible when he died at Brands Hatch in May 1963. He ran wide and looped the loop at Bottom Bend, and he was half thrown out but carried along with the cartwheeling car.

“You have to understand what racing saloons were like then. You’d spend all your budget on the engine, and then take out all the weight you could. No seam welding: just the spot welds the car had from the assembly line at Longbridge or Dagenham. You’d cut out the inner skins on doors, bonnet and boot lid, hack off any unnecessary brackets, replace the glass with Perspex sheet, and even cut out the floor and replace it with a thin sheet of ali. We didn’t know about rigidity, so the car would twist under hard cornering and wave its wheels in the air. Battery, fuel pump and fuel lines sat inside the car with you. Most of us didn’t have seat belts or a roll-over bar, and we raced in jeans and a T-shirt.”

Through Frank Williams Brode got to know the other inmates of the notorious flat at Adrian Court, Pinner Road, Harrow. “They were a group of upper-class public-school boys riding the wave of the great days of Formula 3. Charles Lucas was a bit of a toff, but if you saw him later on, opposite-locking his 250F Maserati through Woodcote, you knew he was okay really. Charlie Crichton-Stuart was part of the Scottish aristocracy and uncle to Johnny Dumfries, who popped up in F1 later, but he was very professional about his racing until he went off to marry the actress Shirley-Anne Field. Bubbles Horsley lived there too: he was trying to make it as a racer long before he became famous with the Hesketh F1 team. Plus there were other itinerant racers who passed through, slept on the floor, used the kettle: Jonathan Williams, of course, known as Willums, a great mate of Frank’s but no relation, and Piers Courage, and others like Chris Irwin, Richard Attwood, Roy Pike, Denny Hulme. Over Whitsun in 1964 a young Austrian I’d never heard of called Jochen Rindt was there. I gave him a lift to Crystal Palace, where he was racing the Winkelmann F2 Brabham, in my Austin A30. He wasn’t very impressed, but he won the race.

“Frank was always positive, always optimistic. Nothing ever seemed to get him down. But he never had any money, ever. Because he wanted to look good to potential sponsors, he would pay Charlie Luke five bob a week to rent his Rolex watch – but then he’d charge Luke five bob a week to wash his car. Once Frank called me urgently at work, asking me to go to the flat and intercept the laundry man, who was due to return Charlie Stu’s shirts. My job was to unwrap the parcel, destroy the laundry list and remove Frank’s shirts, which he’d put in so they’d be cleaned at Charlie Stu’s expense. He did that each week and I don’t think he was ever rumbled.

Best man and chauffeur for Ronnie and Barbro Peterson – the Swede later returned the favour

“One winter afternoon Frank said he urgently needed some cash, fast. Bubbles passed the hat around and said Frank would get the money if he took all his clothes off and stood naked on the embankment by the Metropolitan Line, which ran just behind the flat on its way to North Harrow station. Frank did it like a shot, with us all cheering from the window as the train went past. But when he came back triumphantly to collect his loot, we’d locked the door and he couldn’t get in. The neighbours were treated to the sight of this man dressed only in socks and shoes banging impotently on the door until finally we took pity on him.

“Later on when Frank had nowhere to go he came to live with my wife and me, and offered us £8 a week towards the food. We’re still waiting. But you have to love him. He’s now Sir Frank of course, one of the most successful F1 bosses of all time, 16 world championship titles, majority shareholder of a massive company he has built himself, a private plane or two, and a class act in every way. How he has had the incredible courage and determination to deal so well with his horrendous disability for nearly 30 years now, and carry on being so successful, I can’t even begin to understand.”

For the 1967 season Brode built an extremely effective 1300cc Anglia with downdraught F3 head. The plating business was going well, and Brode was doing a lot of work for Charles Lucas Engineering, where Roy Thomas was building the Titan chassis. Brode decided he was ready for single-seaters, so did a deal with Luke and bought an F3 Titan: “It cost me £2100 complete with spare wheels and wet tyres. I towed it behind a light blue Jaguar 3.8 Mk2 I had then, and the whole rig could cruise at 100mph, although coming back from Snetterton over the hump-back bridge on the old A11 we’d have all six wheels off the ground. I had a few reasonable races with it, and beat an old F1 BRM to win a libre race, but it had a chassis rigidity problem – just spinning it was enough to twist the frame – and I never got it to handle.” So it was back to saloons, and a very quick Ford Anglia with a 2-litre Lotus twin-cam engine – “which was a bigger capacity than anybody else had managed with a twin-cam at that time. We called that car Big Nelly. I had a lot of wins with it. One day at Brands, when I’d won from pole, somebody came up to me in the paddock after the race and offered me good money for it, so I let it go.

“I was already dreaming up the ultimate Ford Escort. We welded cast-iron bores into a twin-cam block and got it out to 2.1 litres. Later on we got to 2.2 litres with a fuel-injected 16-valve Cosworth head, and it revved to 9000rpm. I always wanted my cars to be immaculate, and I decided that this one should be gloss black. But when the painter finished I thought the only thing missing was a Taxi sign on the roof. So to his horror I got a sign-painter to pick out each panel with fine gold lines. That was the car we called Run Baby Run. You didn’t see the JPS Team Lotus colours until 1972, so I reckon they pinched the idea from me!”

Run Baby Run was a superbly prepared racing car, and in Brode’s hands it proved to be almost unbeatable. It won a string of club championships, and made him a star around the British tracks, with a loyal following of fans. “We worked on the car constantly, making detail improvements, saving little bits of weight everywhere. I was more or less winning every race I finished, and the prize money was good. Then I got an Elan for modsports, and that was black with gold pinstripes too. Plus Chris Barber, the jazz trombonist, put me in his Lotus 62 GT. One Bank Holiday weekend I did nine races in three cars in three days, Oulton on Saturday, Brands on Sunday, Thruxton on Monday.

Brodie at Mallory Park in 1971 with first wife Kath

“I did a couple of European long-distance races in the 62 – certainly long-distance for me, because I was used to 10-lappers and an occasional 20-lapper. I did a 500km race on the old Nürburgring in 1972, single-handed. I’d never seen the place before and had to try to learn the 14-odd miles in practice. There were lots of serious drivers entered – Redman, Elford, Merzario, Craft – and there were 96 starters, so the traffic was unbelievable. My Lotus was elderly and overweight, and had dreadfully heavy steering. I was stopping every sixth lap for fuel and a desperately needed drink, and one of my earplugs fell out so I was deafened as well. But somehow I kept going for the full three hours, stayed on the road, and finished 14th, ahead of some of the Chevrons and Lolas. I was well pleased with that. I did another German race four weeks later, at Hockenheim among Can-Am McLarens and Porsche 917s, and came home 14th again.

“With one or two notable exceptions, the driving in saloon racing was pretty clean. One driver whose talent I really respected was Boley Pittard. He was hard as nails, psyched the hell out of the opposition just by looking at them with his dark eyes. He had a sort of aura about him that I never saw in another driver until Ayrton Senna. He bought his racing cars with folding cash in a bag, and you didn’t ask where it came from. Few people had realised how incredibly talented Boley was, and how he was going to the very top, before that F3 race at Monza when his car started leaking fuel before the start and caught fire. On the packed grid that would have been a major disaster, but he stayed aboard, his Dunlop blues soaked with leaking fuel, and drove the car off the grid away from the others before leaping out with his body well alight. He died from his burns a few days later. His was a real lost talent.

“One driver who did make it to F1, and then died in a horribly similar way at Zandvoort, was my dear friend Roger Williamson. When he was racing at the southern circuits he used to stay over at my place. In his little 1-litre Anglia he was the fastest driver I ever saw into and out of a corner, and he had the self-belief, the pure confidence in his own ability, that all great drivers have. In one race at Brands it was pouring with rain and the track was awash. I was on pole and led easily from the start. Roger was well back mid-grid, but in the closing laps I suddenly realised these headlights were closing on me in the murk. I started to drive my socks off, lapping cars right and left, taking chances, armfuls of opposite lock, but the lights kept coming – and I realised it was Roger, with half my engine size, out to get me. On the last lap at Clearways I was sliding wide, he nosed inside me, and he looked across and gave me a big cheesy grin. He beat me to the line by a length, and it was just about the only time I ever got beaten fair and square at Brands.”

The black Escort was also converted to run in Group 2 form, and at the British Grand Prix meeting in 1972 on the long Brands Hatch circuit Brode had one of his best races, vanquishing Dave Matthews’ similar car after a frantic battle resolved by a brave move around the outside at Hawthorns. In 1973 Ford acknowledged his success at national level by giving him a works Group 2 drive.

Same venue three years earlier, driving a Titan Mk3 in the Nottingham Trophy for F3 cars

“I was contesting the British and European Championships, and the car was going in and out of England like a yo-yo. In July we went to the British Grand Prix round at Silverstone, with me now overall leader in the British Saloon Championship. On lap eight Frank Gardner’s Camaro was out in front, and the battle for second was between Dave Matthews’ three-litre Broadspeed Capri, my Escort BDA and Andy Rouse’s Escort BDA. I’d disposed of Rouse and was planning how to get past Matthews when, approaching the fast sweep of Abbey Curve, we came up to lap the 1-litre Mini of Gavin Booth.

“Matthews slammed into Booth’s Mini like it was a snooker ball and his Capri cartwheeled, with him hanging out, arms flailing. The Mini went off and then came back onto the track travelling in the opposite direction, and hit me head-on. I was doing about 130mph and he must still have been doing 70, so it was a 200mph head-on impact. Matthews ended up with two broken ankles, but he was out and about in a couple of weeks. I had a leg broken in three places, a busted jaw, toes, teeth, ended up in hospital for a long time. I needed a couple of corrective operations on my legs, and it took a while to learn to walk properly again. I heard that Booth had head injuries, but when I tried to contact him to make sure he was OK, no record of him anywhere. Really weird. If anyone reading this can help me get in touch with him, I’d be really pleased.

“After I’d been in hospital for about 10 days my mate Roger Williamson, on his way to Zandvoort for his second Grand Prix, called in to see how I was doing. Four days later I was watching the Dutch race on TV from my bed, and I saw him die in the fire while David Purley tried to get him out with no help from the marshals. I got really low after that. I’d never been depressed before in my life, didn’t know what it was, and I thought, I’ve got to think of somebody who is worse off than me. I know, what about that train robber, Roy James?

“So I wrote to him in Gartree Prison and said, ‘I’m banged up like you. When you get out let’s meet for a cup of tea.’ He replied at once, in lovely copper-plate handwriting, so after that we wrote back and forth. I went to get him when he was released and he stayed with me for a while, and Bernie gave him that edge-shaped F1 trophy to make – he was a trained silversmith, remember. We got him a Formula Ford, he did some racing, but he was too old for it, and he broke his leg in a shunt. Then, very sadly, he went back to crime. He got involved in a massive VAT fiddle, then he got banged up again for shooting his father-in-law. He was only 61 when he died.”

Once Brode had recovered from the Silverstone crash, he and Chas Beattie built up a special lightweight Capri with torsion-bar suspension for Super Saloons. Stuart Turner of Ford promised two four-cam V6 Cosworth GA engines, but these were delayed and the car was never able to show its potential. He raced Group A Capris, and then joined forces with Ken Brittain to form Brodie Brittain Racing. BBR developed the Mitsubishi Starion into a race-winning car, and also built up a good business modifying road cars. There was even a Cosworth turbo-powered Starion, and then a Sierra RS500. In 1994 he made his Le Mans debut at the age of 51 in a Chamberlain LMP2 Harrier with Rob Wilson and William Hewland, but retired with suspension failure.

Brode’s relationship with the Williams F1 team remained close. “At Monaco one year we didn’t have enough passes, so to get into the pitlane I put on Alan Jones’s helmet and drove his Williams FW07B to the pits. Only in bottom gear, of course, but it was tempting. Earlier, before Bernie started to take over everything, I remember Frank saying to me after the British Grand Prix, ‘I’m sick of getting £2000 in a brown paper bag when BRM, whose cars only ever last 10 laps, get £5000.’ And then Frank came back from a meeting of all the teams and said, ‘Bernie’s going to take over F1’s commercial interests.’ We thought his reign would only last three or four years, and look, it’s been getting on for 40 now.”

Brodie prepared and raced BSCC Mitsubishis in the mid-1980s

Motorsport Images

Brode’s best F1 friend was his neighbour Ronnie Peterson. “We first met when Frank and I went to watch the 1973 F2 race at Mallory Park, and he and Tim Schenken were there too. Ronnie had a fur coat down to his ankles, blond hair, crystal blue eyes, looked like a film star. After the race Tim asked if I knew a quick route home, and I told them to follow me. So that was a challenge. Frank and I were in my yellow Capri, Ronnie and Tim were in Ronnie’s blue Lotus Elan Plus 2. Of course I tried to lose them. I was going round all these back doubles, passing queues of traffic down the outside, and at one stage I dived down a mud bank and through a garage forecourt. Couldn’t shake Ronnie off. Frank was sitting next to me reading a newspaper, but he’d torn a little hole in it so he could see if we were going to hit anything. We were going into roundabouts at 90mph, up to 130mph on the motorway, and at one point a Morris 1100 pulled into my path and I had to take to the central reservation, clods of earth, Coke cans, fag packets flying, and Ronnie’s right there with me, popping up his headlights so he can see through all the debris. We heard later that Jean-Pierre Beltoise, in his blue Matra, and Jean-Pierre Jarier, in his yellow one, were arrested in a police road block at the bottom of the M1. They’d been ambling gently back to Dover to get the ferry home…

“I loved Ronnie. We did lots of stuff together. Just before Monza 1978 I went to his house with some jam doughnuts, which he loved. He was mowing his lawn on his sit-upon mower. He told me he’d agreed with Colin Chapman that, having followed Lotus team orders all season so that Mario Andretti could clinch the title, he could go for victory in the last two rounds at Watkins Glen and Montréal. But he never came back from Monza.” Even now, 35 years later, his eyes fill with tears.

Brode earned good appearance money down the years racing in Malaysia, Barbados, Guyana and Trinidad. “One year I did the Caribbean Series in a Chevron B8. I bought it before I went for £850, shipped it over, had 28 days of fun, and sold it for £1400. What I liked to do in these places was put on a good show, not just rush away into the distance but mix it with the locals and let them get some glory, and then win the last race. In 2002 I was running the RS500 on a fairly primitive track in Guyana, no run-off areas, no barriers, and just as I’m going into a right-hander, at the split second my right foot is coming off the throttle to the brake, this local hero in a Mazda RX7 whacks me, hard, up the rear. My foot goes down on the throttle, the car goes forward like a missile, I go through a chain-link fence and hit a pickup that’s got two little kids sitting on the tailboard, watching. They were killed. I’ve met some tragedies in my life, but that was just awful. Two beautiful kids, and I saw them dead. You never forget something like that, ever.”

Prodsaloon Capri action

Motorsport Images

Brode kept racing in selected British events, scoring a win at the 2004 Silverstone Eight Clubs in the RS500 Cosworth, 41 years after his first Eight Clubs win. Then he built up a racing VW Vento, and in last year’s Birkett Six Hours Relay he celebrated his half-century in motor sport. Nobody knows how many races he has done in those 50 years, but he has a story from almost every one. In fact he has written, for his private amusement, a book about his racing life, but it’ll never be published. For one thing, it runs to 1450 pages. For another it is totally scurrilous, outrageous and libellous. He’s let me read it, and I can tell you it pays no respect whatever to motor racing’s grand institutions and grandees.

And it’s very, very funny.

In today’s motor-racing world they wouldn’t appreciate Dave Brodie: too in-your-face, too mischievous, too irreverent. But anyone who cheered him on in the 1970s from the spectator banks at Clearways or Becketts, or anywhere else from Castle Combe to Croft, must regret that there aren’t more like him today.

David Brodie

Career in brief

Born: 15/5/1943, Harrow, England

1963 Debut at Silverstone, Austin A30

1964-1969 Assorted club racing

1968 Selected F3 races in Titan Mk3

1969 Run Baby Run Escort makes its debut at Silverstone: many victories follow over the next few seasons. Modsports Elan raced concurrently

1973 Career interrupted by serious accident, Silverstone

1975 Comeback

1980s-90s BSCC/BTCC regular

1994 Le Mans debut, aged 51

2014 Still hasn’t retired…