“Mairesse was very quick, but unstable,” says Surtees. “He got it wrong lots of times, and after the shunt at the Nürburgring Lorenzo became my natural team-mate. Being an Italian in the Ferrari team, he could have played all sorts of political games, but he was completely straightforward and friendly. A good lad…”

In 1964 Surtees won the world title and Bandini finished fourth, winning his first points-counting GP in Austria, at the rough Zeltweg airfield, and finishing third at the Nürburgring, Monza and Mexico City.

At this last race, a championship-decider involving Clark, Hill and Surtees, there was some controversy. While Clark and Dan Gurney ran first and second, Bandini battled with Hill for third place and at the hairpin they almost touched a number of times — until finally they did, which ended Graham’s title hopes.

In some sections of the press much was made of the incident, as if this Italian wild man had cynically tried to take another car out. Indisputably Bandini did have moments of red mist, but none who knew him believed him capable of such a thing — including Hill, whose stylish response was that Christmas to send Lorenzo an LP of advanced driving lessons!

There were no Grand Prix wins for Ferrari in the Clark-dominated 1965 season, Surtees and Bandini finishing fifth and sixth in the World Championship, but Lorenzo did achieve another of his ambitions, winning the Targa Florio with Nino Vaccarella.

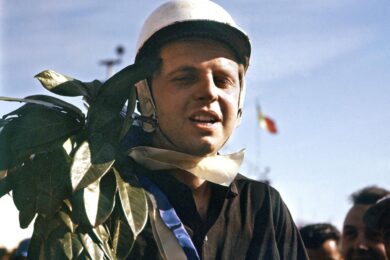

En route to Monza 1000kms win in ’67

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

The following year marked the beginning of the 3-litre Formula 1 and at the first race, Monaco, Bandini’s nimble 2.4-litre V6 car finished an excellent second to Jackie Stewart’s BRM. At Spa, in torrential conditions, he finished third in a race won by his team-mate, but seismic change was coming to Ferrari, for at Le Mans Surtees concluded he could put up no longer with the Machiavellian team manager Eugenio Dragoni. There followed a meeting with Enzo Ferrari, after which a parting of the ways was announced.

“At the time,” says Surtees, “people thought the team was ‘favouring Bandini’, and that was why I left — but that was rubbish. It was true that I’d said at Monaco I should have been driving the V6 car, rather than the 3-litre V12, because it was the quicker car around there, and I was the quickest driver. But that certainly wasn’t Lorenzo’s doing.

“At Le Mans I was sharing with Scarfiotti, and we thought there was a chance that a Ferrari could run at 98 per cent for the 24 hours, and perhaps break the Fords. Then politics came into it: they said Mr Agnelli was arriving, and they wanted him to see his nephew — Scarfiotti — in the car at the start. I said, ‘That blows all our strategy for trying to win’. After what had happened at Monaco, I just felt, ‘I’m no longer part of this family…’

“Lorenzo was terribly upset — in fact, he begged me to change my mind. My leaving made him team leader, and I don’t think that was something he wanted — I don’t mean he was willing to play second fiddle, but it was a responsibility he didn’t want, as an Italian in a very Italian environment. I think it was an error to put him in that position: he deserved better.”