Lunch with Stuart Graham

It’s already a unique claim, being the TT-winning son of a TT winner, but this man embellished it by winning further TTs in big, brawny saloon cars

There are many examples of a racer’s talent being passed on from father to son, and even to a third generation. Indeed there are whole clans, like the Andrettis and Unsers in the USA, where each succeeding generation seems destined for the family business. Damon Hill is the only case so far of an F1 World Champion’s son becoming World Champion (a goal for you there, Nico) but, as editor Damien’s poignant chat with Jacques Villeneuve reminded us in Motor Sport last month, without the Zolder tragedy that took Gilles’ life Jacques too could have been a champion son of a champion.

It would take a qualified psychologist to analyse the complex motivations that drive the son of a racing driver to go racing himself. Yet we can all imagine what it must be like for a young boy growing up in the household of a top racer as he watches his famous father grapple with the pressures and dangers of a racing career, and receive the plaudits and rewards of success.

But what if – as Joann Villeneuve described so movingly last month – that household is riven by tragedy? What must be the effect on a young boy of losing his father just when success was giving him, in his son’s eyes, a sort of immortality? And then, how does a mother feel if she sees her own son move towards the career that robbed her of her husband? They’re all questions I want to ask when I meet Stuart Graham for lunch. A top-level bike racer in the 1960s, Stuart is the only Isle of Man TT winner who is the son of a TT winner. He then switched to cars, and became the only man to win the TT on two wheels and four. His father, the great Les Graham, was World Champion in 1949; but in 1953, when Stuart was just 11, Les was killed on the Isle of Man. Six years later Stuart began racing bikes himself.

Stuart Graham won TTs on two wheels on a Suzuki in 1967

Motorsport Images

He is 70 now, small, it and wiry, the same nine stone he was 50 years ago. He still dons his helmet to enjoy historic outings at Goodwood, but has sold his thriving Honda car dealership. He lives with his wife Margaret and a line-up of cherished classics, from frog-eye Sprite to 300SL Gullwing, in the comfortable Cheshire house they bought in the 1960s. Stuart’s local is the Cholmondeley Arms, a Victorian schoolhouseturned-pub near the Pageant of Power venue.

He tucks into a plate of prawns, whitebait, calamari and crab, followed by Cholmondeley Mess, a welter of strawberries, meringue and cream, and takes a couple of scant sips of Sauvignon Blanc. “The boxer Henry Cooper said to me years ago, ‘Bloody ’ell, Stu, you can put it away, you skinny little bastard. You’re a burner.’ I think that’s a medical term.”

Les Graham started as a teenager on the dirt tracks of his native Liverpool, and was a professional road racer by the time World War II stopped everything. He lew Lancasters and was awarded the DFC for bravery, but would never divulge why. “All we could ind in his logbooks was an entry after a raid over some U-boat pens in 1944 that just said, ‘Bit of a hairy evening.’ As a kid whenever I tried to ask him anything about the war, he’d just dismiss it.

And won the TT on fur wheels, with the green Camaros he raced in the 1970s

Motorsport Images

“After the war he joined AJS as works rider and development engineer, working on the famous AJS Porcupine, so called because of the cooling ins sticking up at all angles on its big fore-and-aft V-twin. It handled a bit like a five-barred gate, but in those days everything did until the Manx Norton came out with a proper frame. But it was quick. In 1949 the first World Championship was run – the car Championship only started the following year – and Dad won it. Suddenly he was someone for everyone to cheer for in austere post-war Britain. He appeared on early TV shows, and there was always somebody coming to the house to take photos or do an interview. I was seven, my brother Chris was four, and we just accepted that we had a famous dad.

“There was a lot of complacency in most of the British motorbike irms. Dad was trying to move development forward at AJS, but it was like pushing water uphill. And by now the 1950 Dad won the Swiss GP again for AJS, but Umberto Masetti took the championship on a Gilera, and MV Agusta were developing a four-cylinder 500 with shaft drive. Dad could see the way the wind was blowing. So when he was approached by Count Domenico Agusta at the end of 1950, offering pretty spectacular money for the time, he signed. Some people likened it to Dick Seaman going to Mercedes in 1937.

“MV’s Four was quick and powerful but pretty crude, and Dad’s brief was to develop it into a winner. In 1951 he didn’t score any points because it broke all the time. In 1952 it was better, and he built up a big lead in the Senior TT. Oil was blowing out everywhere and his boot and the gearchange pedal were covered in it. On the last lap his foot slipped, he missed a gear and he over-revved it, bending a valve. But he nursed it home to inish second. As the year went on the Four became more reliable, and finally at Monza in September Dad won, the MV’s first victory in front of its home crowd. The tifosi went completely mad. Three weeks after that he won the final round in Barcelona, finishing up second in the Championship, three points behind Masetti. So for 1953 hopes were high.

“Dad was approaching 40, and reckoned that after he’d stopped racing his future would still be with MV on the engineering side. So he moved the family to Italy, and found a house in a little village in Lombardy, in easy reach of the MV factory at Gallarati. My brother and I had lessons from a private tutor, and were due to start school in Switzerland that summer. I was obsessed with cars and motorbikes, of course. I’d spend hours wandering around the MV factory, getting in the way. Dad would chuck us in the back of his Jaguar MkVII and take us down the autostrada to Monza when the Grand Prix cars were testing: Fangio and González in the Maserati A6GCMs, Ascari and Villoresi in the Ferrari Tipo 500s. We’d be running wild around the paddock, drinking it all in. Ascari and my dad became good friends: Alberto’s daily driver was a Jaguar MkVII too, so they compared notes.

“Geoff Duke had now moved to Gilera, and everybody was saying 1953 was going to be a vintage season, a head-to-head between Duke’s Gilera and Graham’s MV. The Isle of Man was the first round of the championship, and we all travelled to England for it. My brother and I stayed with my grandmother at Wallasey while my mother went with Dad to the Island. MV had a single-cylinder 125cc bike, effectively a quarter of the Four, and Dad ran that in the 125 TT. It was a hot class in those days with works Mondials and NSUs, but he beat them all. Back at Wallasey there was great excitement that Daddy had won, and everything was looking good for the Senior TT the next day.

“We listened to the radio commentary, done as usual by Graham Walker, Murray’s father. Dad was second at the end of the irst lap. Then suddenly he wasn’t mentioned any more. I supposed he must have retired. The race carried on and inished, and then my aunt arrived. She was obviously upset, and it scared me. I knew something was wrong but I didn’t know what. She took us upstairs, sat us on the bed and told us: Daddy’s not coming back.

“My next memory is of going with my cousin into the park to feed the ducks, and a newspaper photographer sneaking out of the bushes and taking my picture. And next day, walking to the shops, my aunt hurried me past a newsagent, but I’d seen a picture on one of the front pages of a body lying on the pavement beside a crashed motorbike. There were many theories about what happened, some plausible, some outlandish. But the basic story is that as he hit the big bump at the bottom of Bray Hill something broke, or maybe the bike just got away from him. He hit the wall on the other side and was killed instantly. If you go in there, you’re not going to walk away from it.

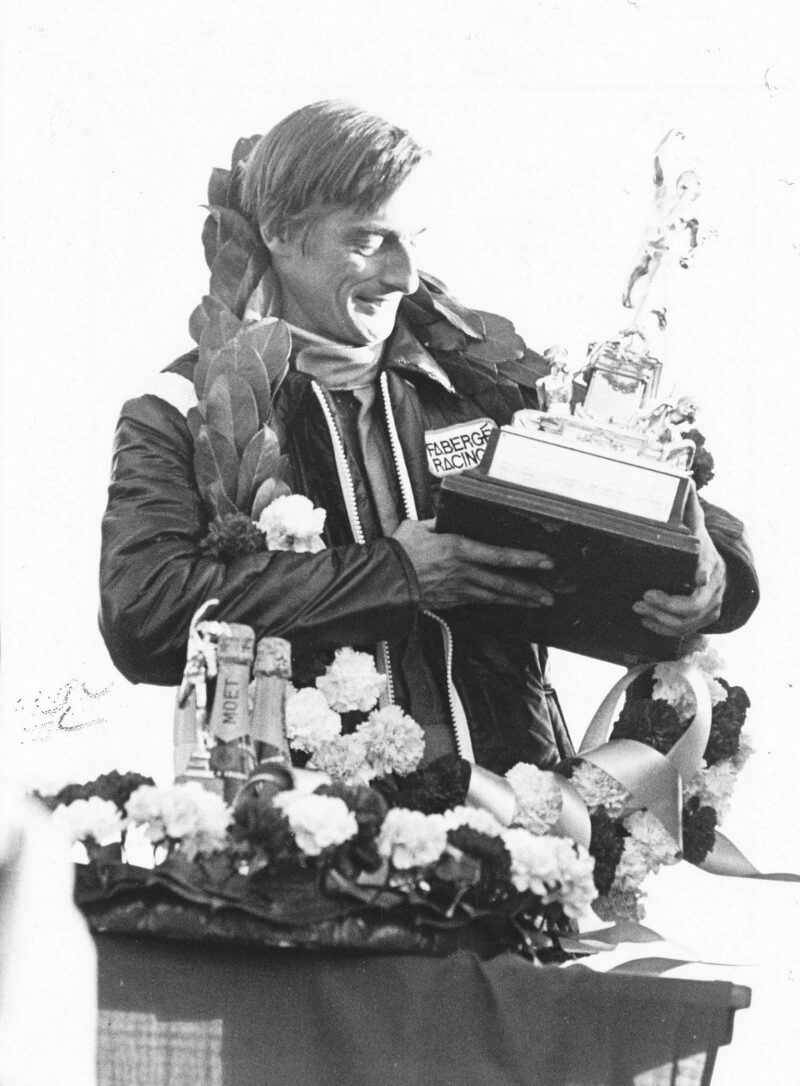

1979 was the final year of current racing, with a 3-litre Faberge Capri

Motorsport Images

“We never went back to Italy. I remember, in the silly way kids do, being worried about my pushbike which was still there. But the Agusta family were wonderful, they arranged for all our personal effects to be sent back to us. In this country the trade barons from Castrol, Lucas and Shell were all very helpful to the widow with her two young boys. She found a house for us to live in, and my brother and I were sent to boarding school. It was a traumatic time, but children are very resilient. Life carried on. It’s amazing how you can get over these things.

“I still had my total obsession with cars and motorbikes, and spent all my time reading car magazines and drawing bikes in my exercise books. So I only scraped a couple of O-levels, but I managed to get an apprenticeship at Rolls-Royce in Crewe. I was 16, and to get to work I got myself a Lambretta scooter. Then I saw a 125cc Honda Benly in a dealer’s window. Somehow I persuaded my poor mother to help me buy it, promising to pay her back out of my meagre earnings. Next thing I’m at Oulton Park, winning my irst race.

“After a few outings on the Benly Bill Webster, a Crewe bike dealer who’d been a pal of Dad’s, started importing Aermacchis, good little Italian production racers. He lent me one for a race, and I inished second. Then it all took off. Bill convinced my mother he’d keep an eye on me, but much later my mother told me she knew I was determined to go racing and there was no point trying to stop me. She never tried to talk me out of it. Considering what she must have gone through, I can’t appreciate her unselfishness enough.

“Being the son of Les Graham opened doors at first. Dad had been universally liked, and always handled people very well. I probably got more attention to start with than my performance merited, because of it. But the big disadvantage, as Damon Hill and others will tell you, is if you’re the son of a World Champion you’re expected to be good. The press love to report it when you go well, but are very quick to say if you’re not up to scratch.

“In 1962 I rode the Aermacchi in most of the national events, and then Bill Webster died suddenly, which was a real blow. Fortunately I’d established a bit of a name for myself, and a chap called Jim Ball offered me a 350cc AJS 7R and a 500cc Matchless G50. The deal was I prepared them and raced them, and if I broke them I fixed them. I was 21 now, I’d inished my Rolls apprenticeship and had a job in their drawing ofice. It was handy being at the Crewe factory: if one of the bikes broke, there was always somebody who’d help you make bits. I did my first 350 and 500 TTs and finished them both, and was getting good results up and down the country. At Rolls I was earning £15 for a hard week’s work, yet in a good Sunday at Snetterton I could pick up £25 in prize money. So I decided it was time to go racing full-time. Margaret and I heaved the two bikes into the back of a little Ford van, hooked a tiny caravan on the back, and off we went to Europe.

Graham inspects proof of yet another TT victory

Motorsport Images

“Matchless had stopped making bikes by then, and my G50 was bog-standard, but I prepared it very carefully. My light weight meant I could run good gearing, so I was pulling a higher top speed. There were lots of tricks to get up to the weight limit – most of the skinnier riders used to drink a pint of milk just before scrutineering – but at Assen the scrutineer said I was under weight and threw me out. This was bad. If I didn’t get the start money, I couldn’t afford to get to the next race. I managed to find a Dutch deepsea diver’s belt with lead weights sewn into it, put that on under my sweater, found another scrutineer, and I was in.

“I was still running my two single-cylinder bikes as we went into the 1966 season. The MV Agusta and Honda multis would be well up the road, then the works Czech Jawa twins, and I usually managed to be next up at the front of the privateer bunch. At Imola, with the old Tamburello with the trees on the outside, I was fourth in the 500 race: Giacomo Agostini won it for MV Agusta, and Mike Hailwood, who’d left MV for Honda, was second. The championship started at Hockenheim. I was fourth there, and fifth in Round 2 at Assen. Then we went to Spa. And, of course, it rained.

“The race started in a total downpour. It was ridiculous, you couldn’t see a bloody thing, and there were lots of crashes. Agostini was out in front, Mike had a problem and retired, and his Honda team-mate Jim Redman had a big accident and took down a concrete post. The visibility was awful, with the spray hanging in the trees like it always did round the old Spa. But I found a rhythm, concentrated on staying on board and not making a mistake. Bit by bit I’d catch the odd rider and pass him, but I had no pit signals because I only had Margaret doing the timekeeping. I just kept going, freezing cold, and after what seemed an age there in the murk was the chequered flag. Agostini had won on the MV, and I was astonished to learn that my old Matchless single had taken second place. A mere privateer, I was third in the 500 World Championship after three rounds.

“Monday morning after any race always used to be Krankenhaus day, when you visited the local hospital to cheer up all your mates who’d been injured. Mike Hailwood and I jumped into Mike’s 330GT Ferrari and went into Verviers to see Jim Redman and my pal Derek Woodman, who rode another of Jim Ball’s bikes. Derek had gone off on the outside of Burnenville and ended up in someone’s front garden, and he was smashed up pretty badly. We found Jim in bed all drugged up, and Mike said, ‘It’s no good you lying there. We’ve got championships to win.’ Jim said, ‘You’d better get young Stuart to help you out.’ I didn’t take any notice at the time; I thought it was just a lippant remark.

“Margaret and I packed up our two bikes, hitched up the caravan, and set off for the next race in East Germany at the Sachsenring, another hairy place I’d never seen before. After a few adventures with the Iron Curtain border officials I drove into the paddock, and was summoned by Honda. The team manager said they’d planned to approach me at the end of the year, but with Jim’s accident they were bringing things forward. Then they led me to their 250cc six-cylinder, seven-gear machine. Until you’ve heard it you can’t really believe it, but it’s the noisiest thing you can imagine, with six tiny cylinders screaming away at impossible revs. It was on a different planet from anything I’d ever ridden before, and I had to go out and practice it before I’d even seen the circuit. It was a baptism of ire, but Honda told me to bring it home, so I had a decent steady ride to fourth place. Getting back on the Matchless for the 500 race just felt so easy. But Honda wanted me to concentrate on their 250, and the two bikes were totally different, so I soon gave up the G50.”

In the Finnish Grand Prix at Imatra, and again on the Isle of Man, Hailwood and Graham inished one-two for Honda on the 250 Sixes. “Having Mike as a team-mate was pretty daunting: it doesn’t do a lot for your confidence when he’s several seconds a lap faster than you in some places. But I was in my first full season of Grand Prix racing, having to learn most of the circuits, and very conscious of my responsibility. By the time we got to Monza, the last European round, I felt more at home.

During practice I said to Mike, ‘What d’you reckon to the Curva Grande? Is it lat, or not?’ ‘Sure, of course it’s lat.’ So I built myself up to it, and finally managed to squeak through totally flat. After the session I said, ‘You’re right, Curva Grande is lat, but it’s a bit hairy.’ ‘What? I was only joking, you brave little bastard.’ Because I was lighter and smaller than Mike I could pull a higher gear than him, and during the race I found I could slipstream past him. So I thought, What do we do here? Is he going to let me win it – because by then he’d clinched the 250 World Championship – and how do I win it? Do I lead him into the Parabolica on the last lap, do I slipstream and do him on the line? And then three laps from the end, the bloody crank broke.

“Mike and Ago were a brilliant pair: they always competed over who could collect the most ladies. Little Billy Ivy was part of all that too, rushing around in his dirty Ferrari 275GTB with the side bashed in where he’d wiped it along a wall in the Isle of Man. Mike was very quick everywhere, but he wasn’t at all technical. When I first rode the Six I found if you didn’t get a down-change on the seven-speed gearbox precisely right, you could ind neutral and the engine would die instantly. At the Sachsenring nobody had warned me about this and I frightened myself silly. I said to Mike, ‘This box is dreadful. Every time I change down I hit neutral.’ And Mike said, ‘Yeah, they do that. It’s a bastard.’ Honda didn’t say much, and there was a language barrier, so we just had to get on with it. And Mike did. Occasionally I’d have a little moan and say, ‘The handling’s not nice.’ And they’d say, ‘Well, Hailwood-san has said no plobrem, and he is two seconds a rap quicker.’ So I’d privately ask Mike what he thought about the handling, and he’d say, ‘Yeah, it’s a bastard, isn’t it?’

As BRDC director, Stuart got involved in historic racing, winning the historic TT too. A 250GTO drive at Goodwood was a later benefit

Motorsport Images

“Agostini was brilliant too, an extremely good rider, but the MV handled so much better. The Hondas had more power, but they were never easy to ride. Of the two – and I’m sure Giacomo would agree with this – Mike was the ultimate, because he could race just as well on a 125 as on a 500. He had a natural ability to adapt to the characteristics of any bike and get the best out of it. Maybe when he got to cars, where set-up was more important, he lost out a bit. He was a very intelligent bloke, an excellent musician on clarinet and piano, and everybody loved him. He wouldn’t have fitted into the modern scene, because he wasn’t dedicated enough. Emerson Fittipaldi told me he was doing an F2 race somewhere, just leaving the hotel after an early breakfast to go to the track for qualifying, and Mike came in after a night on the tiles. ‘Then,’ says Emerson, ‘we get to the track, and he out-qualiies me.’

“After all Mike had done, after all those hard races, his end was so cruel – to get killed like he did, along with his young daughter, by a truck making an illegal U-turn when they’d just nipped out to buy ish and chips for supper. The truck driver was ined £100. “For 1967 my Honda contract seemed a formality. But in December word came from Japan that they were cutting back, concentrating on a single entry for Mike in the 500s, and boring out the 250 for Mike to run in the 350s. Sorry, Stuart, we won’t need you. But then Suzuki came calling. I lew out to Japan in February, tried their 50cc and 125cc machines, saw the four-cylinder 250 they were developing, and signed the biggest contract I’d ever seen.

“That meant adapting to two-strokes, which are completely different from four-strokes. It was a real culture shock. The irst thing is, no engine braking. And because the oil is in the fuel, they don’t like to run on a closed throttle, or they can seize unexpectedly. The 125 would don’t think anybody enjoys rushing downhill. You plunge steeply down on a blind curve, then it bottoms out where another road joins, and as the suspension hits the bump stops it knocks the wind out of you on the tank. Then you go up again and you get well off the ground as you go over the top, with stone walls either side. You feel as though you’re three feet behind the bike all the time, trying to keep up.

Lister-Chevrolet was a regular at Goodwood – which is “just right”

Motorsport Images

“During 1967, even with our twins against the Yamaha Fours, we were competitive all year. I won the Finnish GP, and ended up third in both 50 and 125 Championships. Then, for the final round in Japan, Suzuki got us our 125 Four at last. It was brilliant: not only faster, but better handling too. I had a race-long battle with Bill Ivy on the works Yamaha, until my exhausts started hitting the ground and I settled for second. It was a great debut, and 1968 seemed set fair. Suzuki came up with a 50cc three-cylinder, with even more gears, and 20bhp – that’s 400bhp per litre! And our new Four was going to be magic round the Island. Then in February I was summoned to Suzuki’s Brussels ofice and told they were pulling out.

“The FIM had decided that everything was getting too complicated and too expensive – that sounds familiar, doesn’t it? – and so they’d brought in new rules restricting some of the smaller classes to single cylinders and six-speed boxes. So Honda, Suzuki, Yamaha and Kawasaki all got together and said, we’re off. In fact it suited them, they’d been spending millions, they’d done what they needed to do. Suzuki gave me one of my 1967 bikes to do non-championship events and I was back to being a privateer, preparing it myself just like the old days. I won some races in Italy and Austria, and I did a deal with John Webb to race on his English circuits. Then I bought myself a little garage business in Cheshire and decided I’d retired. I wrote to Suzuki and asked if they’d like their bike back, but never got a reply. Then a young lad called Barry Sheene asked to buy it. It was the first serious bike Barry had. In 1973 with my brother Chris, who’d become a brilliant engine man, I watched a Group 1 race at Oulton Park. It looked like fun, so I got an old 3-litre Capri and did a few races. One day at Silverstone Les Leston’s Z28 Camaro was popping and banging and he was getting nowhere with it. In the paddock we got it running right, and Les blew them all away in the race. He said, ‘You’d better take this thing back to Cheshire and prepare it properly,’ which we did. Then Les phoned to say he was stuck in Hong Kong and couldn’t make Oulton Park that Saturday, so I drove the car to Oulton, stuck the numbers on, put it on pole and cleared off in the race. A week later I did the Martini Silverstone support race for Les, and had a big lead until a tyre punctured. So I decided to find a used Camaro of my own, prepare it properly and get stuck in. I scored eight wins in what was left of the season, and for 1974 it got more serious as Group 1 became the British Touring Car Championship.” Stuart dominated the big class with a string of overall victories, but was beaten to the title by Bernard Unett’s little Avenger which won its class by a wider margin. The Camaro was immaculately turned out – “I’ve always been a fussy bugger when it comes to presentation” – and Stuart had already painted it metallic dark green when he approached Fabergé for sponsorship. His relationship with the Brut 33 brand would last for four seasons.

Stuart’s garage includes two 300SLs and an Austin-Healey Sprite

In 1974 the Tourist Trophy at Silverstone was for GP1 saloons for the irst time. “Most of the other big cars had two drivers, but the Camaro’s appetite for brakes and tyres was high, and I decided I knew best how to preserve the car. With ’bikes, in my era anyway, it paid to be smooth and precise, and when I got to cars I was never one of those flamboyant people with armfuls of opposite lock. If I could do the whole three-hours-plus with only one stop we had a chance. So we came up with a lap time that would be competitive and still eke out the fuel.” Stuart won the race by two laps. For 1975 the TT was run to Coupe de l’Avenir rules, which brought in the quick BMWs from Europe. Stuart found another secondhand Camaro, built it up just for this race with 7.4-litre engine, put it on pole by 3.4sec and won by over a lap. And that year he dominated the big class in the BTCC once again.

He raced his Camaros overseas in 1976, running at Spa, Mugello, Brno and Kyalami with co-driver Reine Wisell. Then he did three years in 3-litre Capris, one of three works-supported drivers with Gordon Spice and Vince Woodman. “Every weekend we were at it in very equally matched cars with the likes of Chris Craft, Tom Walkinshaw, Jeff Allam and the rest. It was terrific fun. In 1968 I put together a complicated deal to run a Capri in the French championship, so I was racing one weekend in England and the next in France. It was all a bit crackers, midnight ferries to Calais, trying to it in some testing, dealing with the sponsors, keeping my garage business running. I did the Spa 24 Hours with Brian Muir as my co-driver, and we led the race before various problems intervened. In 1979 Jacques Laitte drove with us – another wonderful man.

“At the end of 1979 I stopped. I’d had seven good years of touring cars, and there are only so many weekends you can keep going to Silverstone and Brands Hatch. I bought a bigger garage, and became a Honda main dealer. As a director of the BRDC, I got very involved with starting up the Historic Festival, and I found myself being sucked back into racing again, did four seasons in John Beasley’s Lola T70, and took it to South Africa on David Piper’s series. Then one day Bobby Bell, who had an Alfa T33, called to say he was entered for a race at Thruxton and couldn’t make it. After I won that, Bobby lent me his Lister-Chevrolet. I took it home, sorted it out, brother Chris did a great engine for it, and we raced it a lot. I did the Historic TT at Silverstone three times in Paul Michaels’ ex-Equipe Endeavour Aston DB4, sharing with Richard Attwood. We were third, then we were second, and finally we won it, so that was a different type of TT victory to add to the list. In the end we’d just wipe the dust off the Lister’s tyres each September and do the Goodwood Revival with it.

“Goodwood is the only decent circuit left for historic cars. Today’s tracks have been so changed to suit modern racing that they no longer lend themselves to historics. The last thing old cars need is short, sharp corners with lots of stop and start. I don’t think Goodwood is dangerous: it’s just right. But each year it’s getting more serious, more competitive, and you do heave a sigh of relief on Sunday night to have got through another year without the big accident happening. But for me it’s about the honour of being there, and showing off glorious machinery to entertain the public. The Lister has been sold now, but I’ve been lucky enough to be put in Cobra, Galaxie, Project 214 Aston, Healey 100S, Jaguar Mk1, Ferrari GTO, even an Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire. Looking back, I’ve been incredibly lucky. I’ve never broken a bone, on two wheels or four. When I was racing bikes I fell off on average about once a year, but it usually happened on a slow corner. The exception was on the Isle of Man. Up on The Mountain there’s a 100mph right-hander known as Windy Corner. In practice one year I was on a quick one, and I found out how it got its name. In the split second when I needed to peel into the corner the wind coming up the valley caught me side-on, and the bike wouldn’t turn in. I was braking hard, coming down the gears, but I slid onto the grass verge and straight for a stone wall.

Just before the wall there was a ditch, the front wheel went down into it, and I cleared the wall and landed in the ield the other side. I picked myself up, climbed over the wall, righted the bike and rode it back to the pits. My old pal Tommy Robb was caught by the wind at exactly the same spot, but he didn’t clear the wall. He hit it and broke his neck, and he still suffers from it to this day.

“In our era you tried not to take silly risks, because you knew if you crashed you were probably going to hurt yourself badly. We had pudding basin helmets, single-layer leathers, none of the Kevlar body protection they have nowadays. We used to wear golfing gloves because they gave us more feel, which was ridiculous really. Almost every week it seemed a friend, or somebody I knew, got killed or injured. It was always at the back of my mind that I could die, but we all ignore things we don’t want to think about. I believed it wasn’t going to happen to me, even while I knew it very much could happen to me – and had happened to my father. And a different part of me felt fatalistic about it: if it happens it happens. It’s all very strange, and I never really figured it out…”