Lunch with...Tim Parnell

Like his father, Tim enjoyed his time as a racing driver before turning his talents to team management. He went on to take the helm at BRM in the days of Pedro, Jo and Niki

James Mitchell

Tim Parnell was born into motor racing. His father Reg Parnell made his way up from nothing into the 1930s racing scene at a time when Brooklands was proud of its slogan ‘The right crowd, and no crowding’. Driving racing cars was something the social elite did at weekends, along with eating at the best restaurants and going to the right parties. But Reg was driving lorries at 14, and every penny he spent on his racing he had to earn himself. That he ended up driving for BRM, running his own single-seater Ferraris, heading up the works Aston Martin team and ultimately masterminding his own Formula 1 operation is a measure of the tough, no-nonsense determination of the man.

Tim is very much his father’s son. His own racing career was abruptly halted by Reg’s sudden death in 1964; but in any case his tall, burly frame did not make him an easy fit in the increasingly constricted cockpits of the day. Instead his down-to-earth approach, as well as his own experience as a racer, qualified him to take over his father’s team. He went on to navigate the often politically choppy waters of BRM, where he was team manager for six years.

Reg’s racing began at Donington, so it’s appropriate that we go to the Bay Tree in Melbourne for Thai fishcakes, chicken Kiev and warm strawberries with mascarpone. It’s just up the road from the circuit, and within easy reach of Tim’s home in Ashby de la Zouch. His wife Liz Mansfield is a leading light in the equine world, president of the National Pony Society and 2010 Breeder of the Year.

Reg was brought up in a pub in Derby called the Royal Standard – it’s still there, in Derwent Street – and when his elder brother Bill bought an old lorry and operated out of the pub yard he called himself Standard Transport. Young Reg was driving the lorry, and the bus that followed it, long before he was of legal age. When they broke down, as they frequently did, he always believed he could mend them. Says Tim: “He used to live in his overalls for days.

He never thought anything could beat him. He was a glutton for hard work and long hours, preferring that to going to school.”

By the time Reg was 23 the business had grown enough for him to get his hands on a battered Bugatti of uncertain provenance, which he got from a Derby scrap-dealer for £25. It brought him little joy, so he switched to the ex-Hugh Hamilton K3 MG Magnette. He developed this into a 1400cc twin-cam single-seater which was quick but unreliable. Tim’s earliest memory is of going to Brooklands with his parents, hiding under a blanket at the gate because they had no ticket for him.

Brooklands turned out to be Reg’s undoing. During practice for the 1937 BRDC 500 he lost control on the banking, and the MG skidded down into Kay Petre’s Austin Seven. The Austin turned over and Mrs Petre, a petite, pretty Canadian and a popular and successful racer, suffered severe head injuries. The race stewards reported the incident to the RAC, and after a tribunal Reg’s competition licence was revoked for an unlimited period. Reg’s brother Bill told him, “You’d better pack in this motor racing, because the Establishment will never accept you for what you are.”

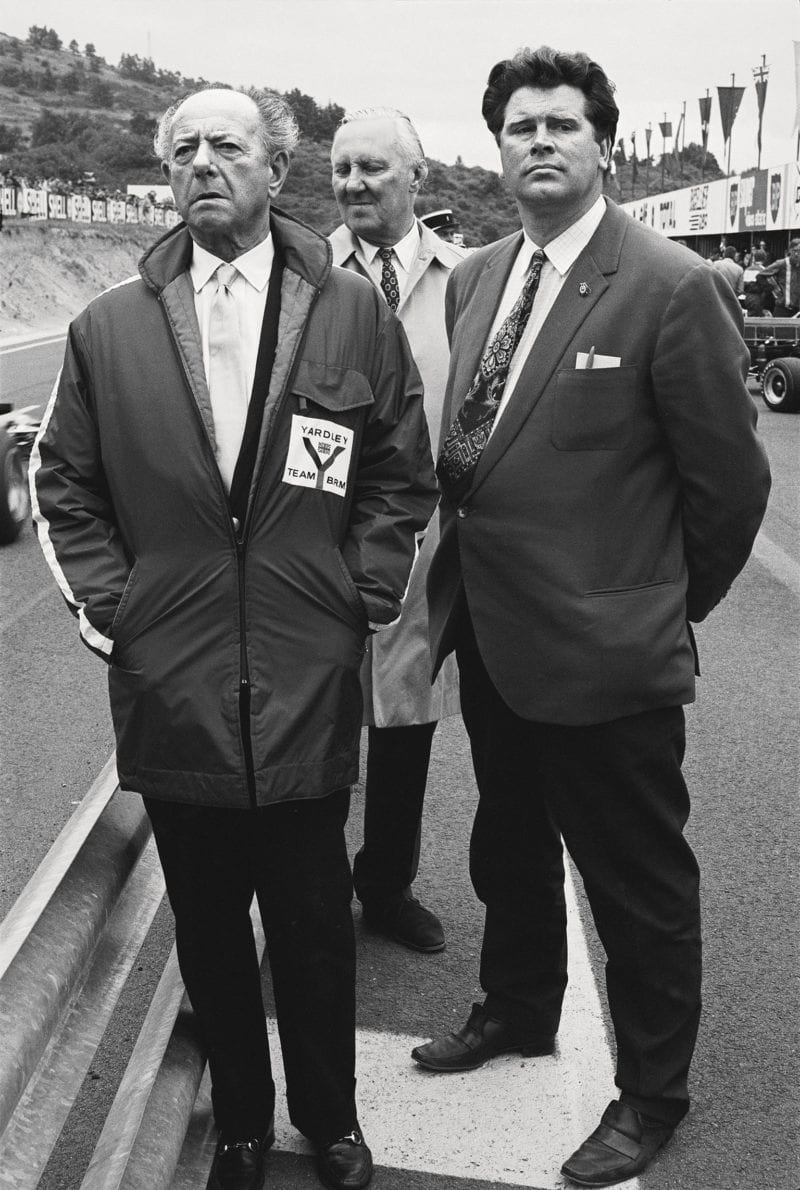

A young Tim with BRM founder Raymond Mays

Motorsport Images

Reg was having none of that, and in 1938 he appealed for the return of his licence. It was refused. Eventually the now recovered Kay Petre made her own appeal to the RAC. “She interceded on his behalf,” says Tim, “and helped him get his licence back for 1939. They became good friends.” When Reg came second in his comeback race at Brooklands, driving the Wally Hassan-built, Bugatti-powered BHW, the first person to congratulate him was Kay.

Reg’s most ambitious project at this stage was to build his own Grand Prix car, which he called the Challenger. “He designed a chassis with independent front and de Dion rear, fitted a supercharged ERA power unit, and rallied round a lot of Derby engineers to help out. You’d be amazed how many parts for that car got machined during the night shift at Rolls-Royce.” But the Challenger only ran at one Prescott Hillclimb before World War II stopped everything in September 1939.

Reg wanted to join the RAF, but his burgeoning transport business meant he was in a protected occupation. Racing cars were totally redundant now, but wherever Reg could find one going cheap he bought it and salted it away. By the end of the war he had an incredible stockpile of over 30 cars, many of which he’d bought in bits or in a poor state – Maseratis, Delages, four ERAs, a Grand Prix Sunbeam, the ex-Reusch/Seaman Grand Prix Alfa Romeo 8C. After the war they were gradually sold off to fund the purchase of more modern machinery. By now Reg had a garage business in Derby, Highfield Motors. He diversified into farming too, specialising in pedigree pigs.

Reg always aimed high. He flew to Italy to talk Alfa Romeo into selling him a 158 Grand Prix car. That was one deal that didn’t get done, although it’s said he took one for a trial blast on public roads north of Milan. He also pursued, unsuccessfully, one of the Mercedes-Benz W154s which had spent the war in Switzerland. But he did end up buying a brand-new 4CLT Maserati from the factory. It’s not clear what ruse Reg used to get around the currency regulations of the day to import this very expensive machine into the UK.

He was now consistently one of Britain’s front-running racers. In 1950, for the first-ever round of the newly constituted World Championship at Silverstone, Alfa Romeo hired him to drive one of its all-conquering Type 159s alongside Fangio, Farina and Fagioli. Tim recalls: “Luigi Fagioli turned out to be something of a pianist, and after Friday practice we all gathered around the piano in the Grand Hotel in Northampton and had a good old sing-song. The King and Queen came to the race, and all the drivers had to line up to be presented.” In the race Reg did exactly what was asked of him, finishing a smooth third behind Farina and Fagioli.

The same year John Wyer signed him to drive for Aston Martin at Le Mans, and then he joined BRM to develop, and race, the recalcitrant V16. At Goodwood in September, in pouring rain, he gave BRM its first two victories. In 1951 Tony Vandervell hired him to drive the Thin Wall Special Ferrari, and he scored a sensational win over the Alfas of Fangio and Farina in the flooded, foreshortened Silverstone International Trophy. Nine days later he won at Goodwood in the same car, breaking the outright lap record. Back in the BRM for the British GP, he scored the V16’s only championship points by finishing fifth, almost asphyxiated and with his legs badly burned from the exhausts.

Tim gets advice from father Reg before taking F2 Cooper to victory in 1958 USAF Trophy at Silverstone

Motorsport Images

Reg was a works Aston driver for seven seasons, driving DB2, DB3, DB3S and Lagonda V12 variants in major British sports car races and classics like Le Mans, Sebring, the Mille Miglia and the Dundrod TT. At Le Mans in 1953 he crashed, and in a typically downbeat remark told Aston Martin’s owner, the tycoon David Brown, that he’d lost concentration because he was “thinking of me pigs”. Keen to make amends, he asked Wyer if he could take the team’s spare DB3S to the Isle of Man for the British Empire Trophy race the following Thursday. On Monday morning he set off from the team’s hotel at La Chartre, with works mechanic Rex Woodgate squeezed into the passenger seat, and drove the DB3S through France to the Channel ferry and up to Derby. After food and forty winks they drove on to Liverpool, took the ferry to the Isle of Man, and arrived just in time for practice. He took pole, ahead of Stirling Moss’s C-type Jaguar and Hans Reusch’s Ferrari, and went on to win the race outright. Two months later he won the Goodwood Tourist Trophy with Eric Thompson.

“He was well into his forties by now,” says Tim, “but he was still very competitive against the team hot-shoes like Moss, Collins and Salvadori. I particularly remember a three-hour international at Oulton Park in 1955. Pete, Salvo and my father were in DB3Ss, and Mike Hawthorn was on pole in a works 3-litre Ferrari. Reg beat Mike by half a minute to win it.” He drove Rob Walker’s Connaught – having the only accident that ever injured him post-war, when he broke his collarbone at Crystal Palace after smiting the sleepers – and he also campaigned his own single-seater Ferraris, a 500 and then a 3.4-litre Super Squalo. In that he scored three victories in the 1957 Tasman Series, including the New Zealand GP at Ardmore. Then he hung up his helmet to become Aston’s team manager.

“The drivers were always relaxed with him because he’d been one of them. And the mechanics loved him. When they were up against it late at night before a race, he’d whip his jacket off, roll up his sleeves and get stuck in with them. But he was hopeless with paperwork, so they had to hire him a good secretary.” This was the redoubtable Gillian Harris.

In 1959, with victories at Le Mans, the Tourist Trophy and the Nürburgring 1000Kms, Aston Martin vanquished Ferrari to win the World Sports Car Championship. Then, deciding the DBR4 F1 car was already outdated, David Brown withdrew from racing altogether. Reg quickly found a new job running the Yeoman Credit team of F1 Coopers, taking Gill Harris with him (until she moved to Australia to marry racer Bib Stillwell). As drivers, he signed John Surtees and Roy Salvadori.

Pedro Rodriguez was fourth for BRM at 1970 Canadian GP, Tim is standing at front of P153

Motorsport Images

****

For some time young Tim had been chafing at the bit to go racing himself. “My father didn’t want me to do it, of course. Year by year he’d lost a lot of his friends, so he knew the dangers first-hand. I was working on the farm by now – I’d done a bit at the garage, but he wanted to get me away from cars – and he certainly wasn’t going to help me. But Alan Smith, his mechanic, was keen to help out, and put his own car on hire purchase to help me raise some funds. We went up to Blackpool to look at a Bobtail Cooper sports-racer. I tried it up and down the front and it seemed all right, so we bought it.

“I raced the Bobtail in 1957, had a few seconds and thirds, and when my father saw I was getting on quite well he encouraged me to get an F2 Cooper.” In this Tim had his share of success on British circuits, including winning a 40-lap F2 race at Mallory Park and the USAF Trophy at Silverstone ahead of Chris Bristow – “a super guy and a hell of a driver, but a bit wild”. His first foray abroad was to the Clermont-Ferrand F2 race. “It was the first meeting at the Auvergne circuit – a fabulous track winding through the hills, but highly dangerous. Bruce Halford lost a wheel in practice, it went bounding over the edge and down the mountain. He asked me to help him find it. I’d never realised there was such a sheer drop on that corner, and I went bloody carefully there after that. But we never found the wheel.” Maurice Trintignant won the race in Rob Walker’s Cooper; Tim was ninth.

After a couple of F2 seasons Tim switched to Formula Junior, racing a Lotus 18 around Europe. “All the drivers would stay in the same hotel, have bunfights in the dining room, play complex practical jokes on each other. Reims was wonderful, sitting in the pavement cafés after practice, drinking champagne. The Junior race there in 1960 was a real slipstreamer. Mike McKee and I were wheel-to-wheel pretty much all the way. He beat me to the line by 0.2sec, but I got the Junior lap record. After the prize-giving we all went to Brigitte’s Bar, and things got a bit jolly. In the end Brigitte called the gendarmes.

“They arrested me and David Piper and put us in the police van, and when they tried to drive off there was a huge clattering. Somebody had wired the back bumper to a tree. There was more uproar, more lads were shovelled into the van, it drove off again and one of the wheels fell off, because someone had undone the wheelnuts. More police arrived, and they shut us up in the jail. One of the mechanics, Stan Elsworth, got a posse together and they all went to the police station and demanded we were let out. When we got back to England we took the champagne we’d won to Friern Barnet, where Keith Duckworth had built our engines in the back yard of the Railway Tavern. We took him to the greasy spoon next door for bacon and egg, with champagne out of paper cups.

Jean-Pierre Beltoise scored famous win for BRM in wet at Monaco in 1972

Motorsport Images

“I ran a 1500cc Lotus 18 in F1 in 1961, and for 1962 I bought a Lotus 18/21 off Rob Walker. We went to Monza and Syracuse, and that little circuit round the houses in Naples. Gerry Ashmore had a four-cylinder Lotus like me, and André Pilette was involved as well. We took the cars around in an old converted Green Line bus, and called ourselves the Three Musketeers. During ’62 I hired out the Lotus for a few races to the motorcyclist Gary Hocking. He took it to Africa and won the Rhodesian GP.” Hocking, born in Wales but brought up in Rhodesia, was double motorcycle World Champion in 1961. Having won the ’62 Senior TT, he was deeply upset by the death on the Isle of Man of his friend Tom Phillis, and decided it would be safer to switch to four wheels.

“Gary was absolutely fearless. On the track, off the track, nothing seemed to bother him. My father said to Rob Walker, ‘You want to sign up this lad, he’s brilliant. I can’t, because I’m running Surtees and the two of them don’t get on. But he’ll make it to the top, no question.’” So Walker signed Hocking to drive his Lotus 24 V8 in the South African series, and he was fourth in the Rand GP behind Clark, Trevor Taylor and Surtees. Then, practising for the Natal GP at Westmead, he crashed fatally.

In 1962 Reg ran what was effectively the works Lola F1 team under the Bowmaker banner, again with Surtees and Salvadori as drivers. When Bowmaker pulled its sponsorship at the end of that season the team became Reg Parnell Racing, running Lolas for Chris Amon and Mike Hailwood. Tim, still racing on his own account, had graduated to a Lotus 24 with BRM V8 power, and finished sixth in the Austrian GP on the old Zeltweg airfield.

“Then it all came to a terrible halt. Just before Christmas 1963 my father was stricken with dreadful internal pains. The doctor came, and said, ‘Christmas in hospital isn’t too bright, Reg, so we’ll get you in afterwards and have a bloody good look at you.’ They operated on him after Christmas, but he got peritonitis, then a blood clot went to his heart, and he died on January 7.” Reg was 52.

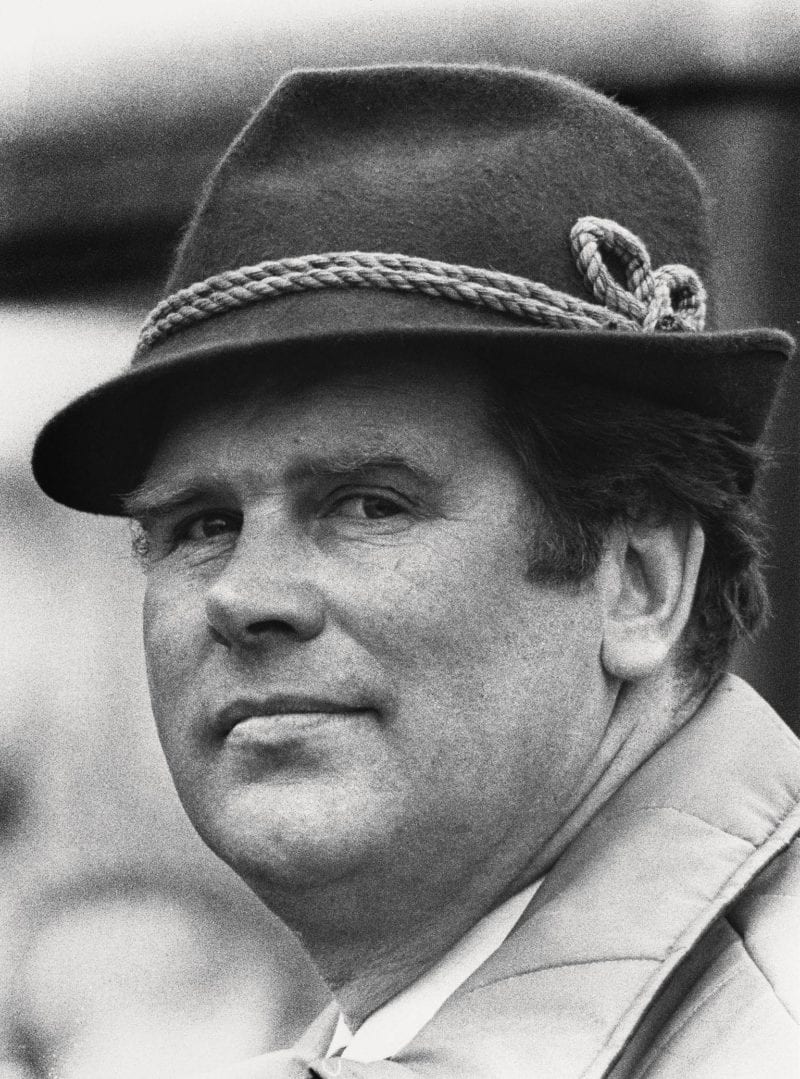

When tony Rudd quit the team 1969 Sir Alfred Owen asked Tim to take charge

Motorsport Images

****

My dad was all set up for the new season with Amon and Hailwood, two new Lotus 25s ordered from Colin Chapman, contracts in place with Dunlop and BP and Champion and Ferodo. They all said to me, ‘What are you going to do now?’ I thought about it, and said, ‘I’d like to have a go, see how it pans out.’ Wally Hassan of Coventry Climax was going to supply the engines – including an experimental unit for Amon with some new tweaks. That would have been something, because Chris was a brilliant driver, and in a Lotus 25 with a really strong Climax V8 he’d maybe have given Jimmy Clark a run for his money. But after Reg died Leonard Lee, the boss of Coventry Climax, decided I had enough on my plate and blocked the deal. In the end we managed to get BRM V8s, some on loan from BRM and some second-hand ones from the Scirocco team, which had gone bust.

“So I was pitchforked into running an F1 team. We were based in Hounslow, total staff of five to run a two-car outfit. How many people does it take to run a two-car F1 team these days? Our mechanics were brilliant lads, you couldn’t have had better: Stan Collier, who’d been with Tony Robinson at BRP, and Bruce Mackintosh, who’s with the FIA now. Amon and Hailwood were the Ditton Road Flyers, living in that famous flat in Surbiton. The police got onto me and said, ‘Look here, Mr Parnell, we’re having a lot of trouble with your chaps in Ditton Road, parties going on day and night, the neighbours are getting no sleep. Can’t you do something?’ I said, ‘I’ll have a word with them, but I doubt it’ll do any good.’ When I tackled Mike he said, ‘I don’t know what the police are complaining about. They come in every night for a drink.’ Then Peter Revson started driving my old Lotus-BRM 24, so he moved into Ditton Road as well. What a gang.

“That year Chris was fifth at Zandvoort, and Mike was sixth at Monaco. And we did a lot of non-championship F1 races, as you could then – Enna to Oulton Park, Syracuse to Snetterton. There were still only five of us plus the drivers, and we worked hard. At Enna Mike spun off into the lake, and scrambled out quick because he’d heard about the snakes that lived in it. Colin Chapman – who was always good to us – lent us a spare Lotus-Climax so we could run two cars in Austria the next week.”

In 1965 the team carried on with the Lotus 25s, still with BRM engines. “Sir Alfred Owen never forgot that my father was the first man to win a race in a BRM. Tony Rudd had Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart in the works cars, but he was keen to sign young drivers and give them F1 experience. So in return for our engines we ran Richard Attwood, who finished in the points for us at Monza and in Mexico. Our other car was driven by Innes Ireland, who was pretty relaxed about everything. In Mexico he didn’t even turn up for practice. Bob Bondurant was hanging around, so I put him in the car. Innes finally appeared, laughing and joking about getting lost on his way to the circuit, and it really got my rat up. So I fired him, and Bondurant stayed in the car for the race. But Innes was one of the old school, a Duncan Hamilton type if you like, never one to stick to the rules. We soon made it up, and a few weeks later he was driving for me again in the South African series.

“When BRM did the Tasman Series with Hill and Stewart, Tony Rudd asked me to fly out to run things. I got to know Graham very well on these trips, and to me he was a great, great man, the best ambassador our sport has ever had. At parties he’d be standing on the table, doing a striptease and singing a boating song, but at the track he expected perfection. He knew what he wanted, down to the last shock absorber setting, and he made sure he got it. He was a hard man, and the mechanics respected him for it.

Through all his racing years, , Tim also oversaw the family farm, started by Reg

Motorsport Images

“I admire Jackie Stewart for being one of our great drivers, and you’ve got to give him credit for all the work he did to make motor racing safer. But he could be a bloody awkward bloke. He and Graham had a few arguments, about engines and such, and I’d have to go in and sort it out. In 1967 for the Lady Wigram Trophy at Christchurch Stewart and I had a big row about tyres. BRM were on Goodyears then, but he decided the Firestones were better and went to [Firestone racing manager] Bob Martin and tried to arrange a switch. I pointed out that we had a Goodyear contract, so he insisted I phone Tony Rudd – it was the middle of the night in England – and get him to agree. I got Tony out of bed, but he said only Sir Alfred could make that decision. I wasn’t going to wake him up in the small hours, so I stayed up until it was a polite time to call. He said if I agreed to it, it was OK with him. So Stewart ran on Firestones.” But Jim Clark led from start to finish, while ironically a marker tyre clipped by Clark’s wheel hit the BRM and broke an oil line, putting Stewart out.

For the new 3-litre F1 in 1966 Tim plugged on with the old Lotus 25s, now running 2-litre BRM V8s. “We ran Mike Spence, a lovely fellow, and a superb test driver. He’d do a few laps, come in and tell you precisely what was wrong and what needed doing. You’d do what he asked and he’d respond at once with a lap time. In the Parnell sports car that Les Redmond designed for us he won the last-ever international race at Goodwood in the 1966 Easter Monday meeting. For ’67 he joined the BRM works team. Then, when Clark was killed in April ’68, Colin asked BRM if he could have him back for Indianapolis to drive the Lotus turbine. A month to the day after Jimmy’s death, he went into the wall. The right front wheel hit his helmet and killed him. Up to then he’d done the second-fastest Indy lap ever, and he’d never seen the place before. Mike is another of the real unsung heroes.

“In 1966 John Frankenheimer arrived in F1 with his crew to make the Hollywood movie Grand Prix. Most of the film cars were disguised F3s from Jim Russell, but we’d turn up with our F1s two or three days early for each Grand Prix so they could get the shots they wanted. Spence’d go round with a tape recorder in the car, to get the right engine sounds and gear-changes for each circuit. When they were filming pit sequences Frankenheimer would say, ‘Does this look right to you, Tim?’ and I’d say, ‘You want a few more mechanics in shot.’ I had a great relationship with him, and Jim Garner was wonderful. Not a bad driver, either. We’d put him in one of our cars and off he’d go. Yves Montand was a bit moody, but that lovely girl, Eva Marie Saint, we all got on with her. Françoise Hardy, too.

“At Monza the Italian organisers asked us to put Giancarlo Baghetti in one of our Lotuses. It was painted white and blue for that race because it was meant to be Jim Garner’s, I mean Pete Aron’s, in the film. But during practice Eugenio Dragoni, the Ferrari team manager, came over and said, ‘Enzo Ferrari would like a word with you.’ I walked over to where the Old Man was sitting and was introduced. He said, ‘I remember il grande Parnell, when he drove Vandervell’s Ferrari, and when he won in New Zealand for us. Take our spare 246 for Baghetti. We will provide the mechanics, but it will be entered by Reg Parnell Racing.’ The film people went crazy, because they’d lost their white and blue car. So overnight we repainted Spence’s car to suit the script, and he finished fifth. Baghetti was 10th.”

In 1967 Reg Parnell Racing became effectively the BRM B-team, running a third P261 with 2.1-litre V8 for Bourne protégés Piers Courage and Chris Irwin. “Piers was a wonderful driver, and very, very serious about his racing. I’m sure he’d have been World Champion if he’d lived. We swapped Piers and Chris around to give them both experience, and to be honest there was nothing between them. At the French GP at the Le Mans Bugatti circuit, Stewart and Spence were in the works H16s, we had Chris in the little P261. After first practice Jackie told Tony Rudd the H16 was rubbish on that circuit, and insisted on taking over our car. So Chris drove the H16, did a great job, and was running fifth late in the race when the engine let go. After that he more or less stayed with the H16 for the rest of the season, finished seventh at the ’Ring, and put it on the fourth row in Canada alongside Stewart’s H16. It was terrible what happened to Chris [his near-fatal accident at the Nürburgring in a Ford F3L sports car in ’68]. It destroyed him, his whole life fell to pieces.

****

We continued with Piers in 1968, while Pedro Rodríguez and Attwood drove the works cars. Then in 1969 the great John Surtees joined BRM, and he didn’t half cause some bloody trouble. You can’t blame him: he wanted to win, and he kept insisting on all these things, and I think Tony Rudd had had enough by this time. He’d been 17 years with BRM, he was a really first-class engineer, but in August he said to Sir Alfred, ‘I’ve had this offer from Colin Chapman, and I’m going to take it.’ It was a big blow for BRM. Then Sir Alfred said to me, ‘Would you like to take over running the team?’

“He was marvellous to me, was Sir Alfred. He set the budgets and strategy for the team. I’ve never known anyone with such a work schedule: chairman of 85 companies, chairman of various charities, and on Sunday he’d be in a Methodist chapel, preaching to the congregation. So he never came to Sunday races, only Saturday Grands Prix and Bank Holiday events. But in 1969 he had a heart attack, and that was when Louis Stanley got more involved. He was married to Sir Alfred’s sister Jean, and he’d always been in the background, bloody interfering. He gave himself such airs. In America he used to call himself Lord Stanley, and of course the Americans swallowed that. He lived in a suite in the Dorchester, paid for by Rubery Owen. What a waste of money. He’d summon us to meetings: once there were 14 of us from Rubery Owen and BRM, marketing people and all sorts, for lunch in a private dining room. It was all because Mrs Stanley had decided it might be a good idea if the BRM badge was changed to a mouse wearing a crash helmet, and we were all summoned to discuss it.

“But I always got on well with Jean, and when I had a problem with Big Lou she could usually calm things down between us. I told him he could do what he liked at the factory with the organisation, but at the track I had to take all the decisions, and if he didn’t like that I was gone. I had to move to Bourne to do the job: luckily I had a good farm manager to keep things going at home.

“As a businessman Stanley was hopeless, but he was good at impressing prospective sponsors. He brought Yardley into F1, and then he got Marlboro – although that was really down to Jo Siffert, who introduced them to BRM. Once they were on board, Stanley seemed to go out of his way to upset them. But he did set up the Grand Prix Medical Unit, and gave tremendous help to injured drivers, getting them the best medical treatment. He was very good at that.”

At chez Parnell, motor racing and equine memorabilia are displayed together

With the departure of Rudd the talented Tony Southgate joined BRM and designed the P153. Rodríguez returned to lead the team, scoring a glorious victory at Spa, and for 1971 Jo Siffert was signed, with Howden Ganley as number three. “Tony Southgate was absolutely brilliant, although in the end Big Lou upset him, of course. That’s why he left and went to Shadow.

“Pedro and Jo were an incredible pair, always very competitive with each other. They were sports car team-mates at Porsche too, and they had the same rivalry there. That’s how they worked. Pedro was an extraordinary man, he had real mystique. We used to get more fan mail for Pedro than any other driver. But he kept to himself, was never really close to the others. When I asked him why, he said, ‘I don’t want these people to know how I think, how I really am.’ As for Jo, he gave his all in a car. He was so determined and brave on the track. But when he got out of the car he changed completely, his hardness would melt, he’d be friendly and relaxed. If you push me to say who was the better driver, I suppose I’d have to say Pedro. But they were both very good, both real racers.

“That July Pedro was meant to be driving our Can-Am car in a race in Germany, but it wasn’t ready. So he drove a privateer Ferrari, a tyre failed, and he was killed. Three months later Jo died at Brands Hatch. A bracket locating a top radius arm broke, the car turned over and caught fire, and he was trapped. I had to identify him, and there wasn’t a mark on him. His only injury was a broken ankle. He’d suffocated in the fire from lack of oxygen. Two dreadful, crushing tragedies.

“For 1972 Jean-Pierre Beltoise joined us, and had that brilliant win in the rain at Monaco. We’d just got Marlboro on board, and they were thrilled to bits, because even then Monaco was televised worldwide. Jean-Pierre had a weak arm, the legacy of a crash he had early in his career, and because that race was wet it was easier for him to cope. After he finished second in the Silverstone International Trophy, just behind Emerson Fittipaldi’s Lotus, he said, ‘Tim, if I had two good arms I would have won today.’

“Stanley was always doing deals with different drivers. In 1972 alone we ran Beltoise, Ganley, Peter Gethin – who’d won that slipstreamer at Monza for us in ’71 – plus Reine Wisell, Helmut Marko, Brian Redman, Jackie Oliver again, even Bill Brack and Alex Soler-Roig. We often had four cars in a race. In ’73 the young Niki Lauda joined us. He only scored two points all season, but he was incredibly dedicated. He’d test all day long, and somehow you knew he was going to make it. Clay Regazzoni was with us that year, too. A real tough guy, but very likeable. Terrible what happened to him in 1980, paralysed after his Long Beach accident. But he just got on with his life.

“Roger Williamson had been doing great things in F3 and F2, run by Tom Wheatcroft. So I suggested we give Roger a run at Silverstone. Tom said, ‘I don’t want no contracts signed or nothing’, and I said, ‘No, it’s just a test.’ Well, Roger went faster in that P160 than a BRM had ever been round Silverstone. At once Stanley jumped in with both feet and tried to get him to sign a contract, and there was a big falling-out with Tom. It was a few days later that Roger was killed at Zandvoort in the Wheatcroft March. A Dutchman gave me photos he’d taken which showed the front tyre exploding, knocking out the front suspension, and the car going upside down. I showed them to Max Mosley at March, and to Goodyear, so they knew what went on.

“By 1974 I’d had enough of BRM. Sir Alfred was very ill, and his sons decided the Owen family could no longer back the team. Louis Stanley was becoming more and more difficult: he was going to fire Mike Pilbeam, the designer, Peter Windsor-Smith the engine man and several other people. I thought to myself, this is going down the bloody drain, this is. It’s time to retire.

“So I went back to the farm. Also I managed Mallory Park and Oulton Park for John Webb until he sold up. Then Tom Wheatcroft asked me to manage Donington. I stuck that for a year but, of all the people I worked with, Tom was the most difficult chap of all, always getting into litigation with everybody.” Tim went on to be very involved in Silverstone as a director, and then vice-president, of the BRDC.

***

ooking back, Tim sees his 10 hard seasons in F1 management as a time when Grand Prix racing went through dramatic change. “In the old days you hung around after the race to get your start money off the organisers. I remember at Silverstone queuing outside a Nissen hut with Franco Gozzi: Ferrari and BRM kept waiting in line in the rain to be paid. Then Bernie Ecclestone came along and changed all that. He told us what he thought he could do, and we all said, ‘If you can get us that, Bernie, we’ll go along with it.’ At first Ferrari wanted to do their own deals, until Bernie showed he could get them more than they were getting themselves.

“I used to go into my local in Derby on a Monday evening and they’d say, ‘Where were you last weekend, Tim? Belgium, eh? How did you go on?’ Now I go into the same pub and they’re all bloody experts, telling me about KERS and Drag Reduction Systems, arguing about what happened on lap 37. That’s what Bernie’s done. He’s taken motor racing into everyone’s home. He’s changed F1 for ever.”