While the DBR1 failed to offer consistent opposition to Ferrari’s new Testa Rossa in 1958, the DBR4 sat under a sheet during a season that would change the face of racing cars for all time. True, the front-engined hierarchy held sway – thanks in no small part to the outstanding contribution made by the combination of Tony Brooks, Stirling Moss and Vanwall – but by the close of play all bar the most blinkered of constructors knew horse-before-the-cart architecture had had it. The DBR4 went from being a state-of-the-art racer to something close to obsolescence all in one short season during which it turned not a single wheel in anger.

Of course we are all brilliant with hindsight on our side, and the decision not to race it in 1958 now seems nothing like as curious as the decision to wheel it out instead for ’59. By then it must have seemed clear as day that the little mid-engined Coopers would run rings around it.

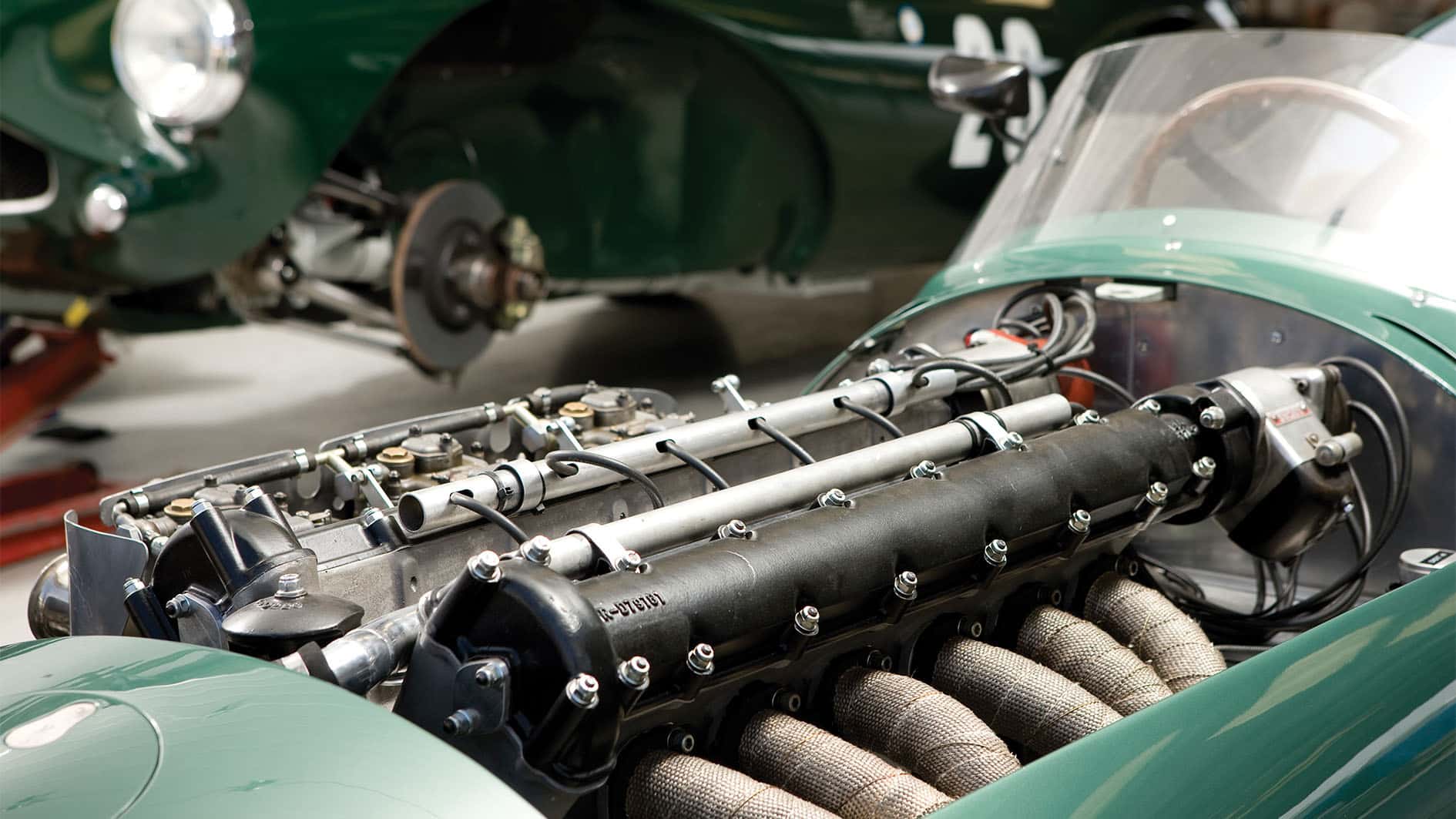

Ted Cutting’s design for the DBR4 was entirely conventional, conservative even. The chassis was of spaceframe construction, as was the norm in the era, and followed closely the principles of the DBR1 sports car. Front suspension was by wishbones and coil springs as you’d expect, while the traditional De Dion rear end (mounted behind the rear axle line instead of ahead like the Maserati 250F) was sprung by torsion bars. The motor was the same twin-cam, two-valve straight six developed for the DBR1, but stroked down from three litres to 2.5 to comply with the regulations of the day. Even its Girling disc brakes were no more than you’d expect from a newly developed grand prix car of the era.

Engine is same as that in DBR1 sports car

Matt Howell

Interestingly – and embarrassingly given the fact that Aston Martin was owned by a gear-making company – the slow and awkward David Brown transmission, the only threat to the love affair that tended to develop between the DBR1 and those who raced it, was used at first in the DBR4, but ultimately replaced by a Maserati transmission originally intended for the V12 250F. And like the ‘offset’ Masers, the shaft emerged from the engine and ran at an angle across the car and beside the driver to the transaxle at the rear, helping lower the driver in the car. Driving duties fell to Roy Salvadori and Carroll Shelby, for while Aston Martin could call still upon the services of Moss in sports car racing, he was committed to Coopers for F1.