Lunch with... Tim Schenken – Australia's sports car ace

This affable Aussie made it in F1 and sports cars, and ran his own team, before helping to shape motor sport back home

Kristian Gehradte

What do racers do when they stop racing? All that competitive edge has to go somewhere. Many attack the world of business with the same will to win that they displayed in the cockpit. Others find ways to stay close to the sport, running a team, or even building racing cars. A handful join the media circus as a commentator or pundit.

A few, inevitably, stand on the sidelines, complaining that things ain’t what they used to be in their day.

And one or two acknowledge what they got out of the sport by putting something back. Tim Schenken is one of those. His professional racing career included almost 40 F1 starts, and spells as works driver for Ferrari and Jaguar. He also went the team manager route, helping several young drivers on their way, and he became a race car manufacturer as well. But in 1984 he decided to return to Melbourne with his family and joined the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport, which governs and administers the country’s racing. Today, 25 years on, he’s still there, as Director of Racing Operations.

Tim and Brigitte, his wife of 35 years, live within walking distance of Albert Park, in a stylish modern house near the sea. At The Stokehouse, a beach restaurant full of Melbourne’s beautiful young things, we eat seared scallops, red snapper and cuttlefish. Tim is 65 now, tall and rangy, thinner on top but apparently still the same weight as the skinny, ambitious would-be racer who, 44 years ago, landed in England with empty pockets.

His chemical engineer father emigrated to Australia from Germany in the 1920s, and married a politician’s daughter. Growing up in Melbourne, Tim was fascinated by the hillclimb special raced by the father of a school friend. By 13 he’d built himself a crude go-kart out of a bedframe from the local dump, powered by a scrap Villiers engine, and roared around the local dirt roads. When he was old enough to drive legally he’d borrow his mother’s Simca Aronde, saying he was going to a barbie with some mates, and then go on a club rally.

“One Sunday morning at Calder there was a straight-line sprint, which didn’t require a competition licence, but in the afternoon they had proper circuit races, which did. Of course I didn’t have a licence, but when the cars were lining up at the paddock gate to go out for practice I joined the queue in the Simca, and nobody checked, so I went out and thrashed round. They put up the list of times and to my amazement I saw they’d given me a grid position for the race. So I did it in my mum’s Aronde, and I won a trophy. I hid it in the roof of the garage. Years later, when my parents were selling the house and I was racing in England, I got my brother to go in and retrieve it.”

Tim rates his F3 win at Crystal Palace as the best in a classic 1969 season. Here his Brabham leads Ronnie Peterson’s Tecno (67), Alan Rollinson’s Brabham (61), Reine Wisell’s Chevron and Bev Bond’s Brabham

Motorsport Images

When Tim did get his CAMS licence he bought a race-prepared Austin A30 with Sprite engine and alloy crossflow head. He got a clerical job in the Melbourne BMC dealer, so he could scoop up any broken bits that had been changed under warranty and repair them for his racer. “Every lunchtime I would walk two blocks to the overseas magazine store to see if anything had come in off the boat: the green one, Motor Sport, the red one, Autosport, or the yellow one, Motor Racing. I read them cover to cover, taught myself all about European racing.

“The A30 wasn’t very competitive, but in 1964 Rocky Tresise, an up-and-coming Melbourne driver, was selling his Lotus 18 because he was joining Lex Davison’s team. I borrowed the money from my dad to get it. Now I was in a proper racing car, and I started attracting a bit of attention at Calder, Winton, Tarrawingee, Sandown Park. I also did hillclimbs in a friend’s JAP-powered special. It was so small and powerful for its weight I was able to beat all the local 1100 Coopers, and I managed to win the Australian Hillclimb Championship.

“Then, out of the blue, Lex Davison called. He was a major figure, of course, and a real hero of mine. He told me he was going to retire, and Rocky Tresise was going to take over his big single-seaters. He’d watched me in the Lotus 18, and he wanted to put me in his Elfin. It was unbelievable for me.”

Davison, four times Australian Grand Prix winner in HWM, Ferrari and Cooper-Climax, had been a cornerstone of Australian motor racing for two decades. Barely a week after his conversation with Tim, Davison’s Ecurie Australie was running at Sandown Park: 41-year-old Lex in an ex-Denny Hulme Brabham, 21-year-old Rocky in an ex-Bruce McLaren Cooper.

During Saturday practice the Brabham crashed heavily going onto the back straight, and Davison died a few hours later.

“Because of Lex’s status in Australia, there were hundreds of people at his funeral in St Patrick’s Cathedral, including Jack Brabham and Bruce McLaren. I’d never been to a funeral before, and it was dreadful. On the coffin was a chequered flag and his helmet and gloves. I didn’t know anyone, I just hung around on the edge of it, very muddled about it all.”

The following weekend the team was entered for the Australian GP at Longford, and Rocky Tresise persuaded Lex’s wife Diana that he should still run the Cooper, as a tribute to Lex. He made a bad start, and was carving through the field at the end of the first lap when he got two wheels on the grass. The Cooper went out of control, through a fence and end-over-end. Tresise and a photographer were killed.

In his dominant Merlyn MKII at Brands during 1968 Formula Ford campaign

“It was terrible, Lex and Rocky dying on consecutive weekends. It just stunned everybody. The thing was, the weekend after Rocky’s crash I was due to run for the first time under the Ecurie Australie banner, at Calder in my Lotus 18. The newspapers got hold of it and were speculating whether it would be three fatal crashes in three weekends. I went to see Diana Davison, and she pleaded with me not to race at Calder. I was under a lot of pressure not to drive; I felt I couldn’t talk to my parents about it, but all I wanted to do was go racing. I was a very confused boy.” Tim did race the Lotus at Calder, but entered under his own name. The transmission broke on the startline.

“I knew I was going to have to get myself to Europe, so I left the Lotus with my father to sell, and my friend Brian Andrews and I scraped together the fares for a slow boat to Southampton, via Papua New Guinea, Port Said, Suez, Athens and Naples. Included in the deal was the bus ride from Southampton to Earl’s Court, and two weeks in a bedsit in Kangaroo Valley. When we arrived, in November 1965, the first thing I did was find the Autosport offices in Paddington, introduce myself to the assistant editor, Paddy McNally, and persuade him to put a snippet in the magazine saying that the Australian Hillclimb Champion had arrived in the UK and was open to offers. I waited for the phone to ring, but it must have been a slow week…

“Brian and I persuaded Graham Warner at the Chequered Flag in Chiswick to take us on as mechanics in the servicing bay. Brian was a qualified mechanic, I certainly wasn’t, but he carried me: I did the oil changes and the simple stuff, and he helped me with anything more complicated. At weekends I went to races, got to know people, Nick Syrett at the BRSCC, Grahame White at the BARC. Then at the Flag somebody traded in a twin-cam Anglia race car that had been rolled. I talked Graham into letting me rebuild it. He provided the parts, I did the work in my spare time, and during 1966 I learned the English circuits in that.

“Chas Beattie ran the Flag’s race team, the F3 Brabhams which Chris Irwin and Roger Mac drove, and the 7-litre Cobra, working out of a railway arch under Stamford Brook station. Every time a District Line train went over, paint used to fall from the roof. When the money from the 18 came through I bought an ex-racing school Lotus 22, with tin wheels and rubber suspension bushes. Chas let me use old rose joints and shockers out of the rubbish bin, and I got it sorted and did F3 with it in 1967. I took it around in an old laundry van, with a plywood box on the back where the nose stuck out. Then at Crystal Palace one of my welds broke on the front suspension. I never was much good at welding. I hit the sleepers, and that was the end of the Lotus.

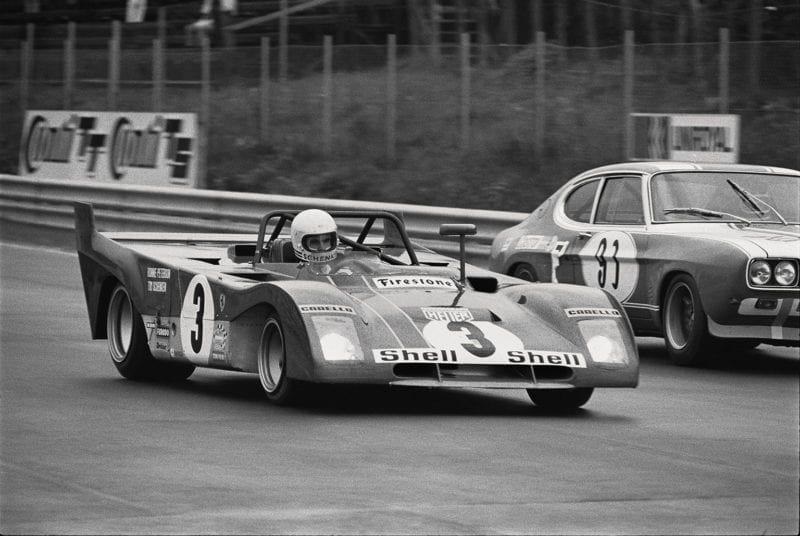

Victor in the “nervous” Ferrari 312P at the Nurburgring in 1972

Motorsport Images

“Formula Ford was just getting off the ground, and Selwyn Hayward of Merlyn was looking for somebody to run a semi-works FF car. He’d seen me pedalling the old Lotus, so he asked me to a test at Brands, and I ended up with a loaned Merlyn chassis and an engine from Chris Steele. Chas had set up on his own now, in a shed by the old Aston Martin works at Feltham, and I used a corner of it to prepare the car. Chas was a huge help. He taught me that it’s what you do before you get to the circuit that matters. Get all the wheels pointing in the right direction, get all the corner weights right. Then, if there’s a handling issue when you get there, it’s not because of the basic set-up.”

The impact that Tim made on the 1968 racing scene was devastating. Straight away he dominated Formula Ford so absolutely that by April he’d been offered a competitive F3 seat by Rodney Bloor, who ran a Chevron under the banner of his Manchester business, Sports Motors. “I’d do four races in a weekend: F3 and FF on Saturday at Oulton, F3 and FF on Sunday at Snetterton. In FF I had the right car and the right engine, always made sure my gear ratios were spot-on for each circuit. With the Chevron there were some handling problems to start with, but once I got my confidence with it I was away.” In that hectic season Tim clocked up 36 victories, and won both the British Formula Ford Championship and the British Formula 3 Championship – a feat never achieved before or since. And, inevitably, he won the season’s top Grovewood Award. “I suppose I was the dog’s bollocks then. We did some European FF races, too. Went to Spa, the old 8.7-mile road circuit, for a support race at the Belgian GP. You only needed to brake for La Source and at the top of the hill, Les Combes, and maybe a touch at Stavelot. So, pretty much flat for over seven miles, pulling 132mph down the hill.

“I also did the Monza and Spa 1000Kms races. John Raeburn, another Aussie who worked at the Flag, got me a ride with him in Andy Cox’s old GT40. At Spa the ride height was all wrong, and through the fast bits you could turn the wheel and nothing happened, like being in a speedboat. It frightened the life out of me. Then for the race it rained. Real Spa rain. We only had slicks, we couldn’t afford wets. John started, and at the end of lap one Jacky Ickx arrived in a plume of spray, down the hill, up Eau Rouge and out of sight before anybody else appeared. Then everybody else came through, and after a pause John came gingerly round La Source on his slicks. We hung the board out for him, he gave us a little wave – and spun, clouted the bridge parapet, put it in the ditch. I’ve never been so relieved in all my life.

“For 1969 Rodney ran what was effectively the works F3 Brabham, the new BT28. It was painted red and black, because we had a little money from Guards cigarettes. The works team consisted of an old Ford Zephyr with the back seat and rear bulkhead removed, four wheels and a nosecone in the back, spare engine and gear ratios in the boot, towing an open trailer with the car on it. That’s how we went around Europe, me driving, my mechanic John Schofield in the passenger seat, terrified because we always towed at 90mph. We thought we were pretty professional in F3 then. Today it would seem like amateur hour, but with the narrow power band on those little 1000cc screamers, gear ratios were crucial. At Brands Hatch, for qualifying you’d put in an extra second gear in the first gear position just to suit Druids, but then you’d have to change it to a normal first for the race to make sure you could get off the line. So you’d qualify using all four gears, and then race only using three gears. You’d keep all your secrets, never tell any of your rivals what you were doing. Then at Brands this lanky blond Swedish kid came up and asked me what ratios I was using, and I don’t know why, but I told him. That was Ronnie Peterson. We were friends from then on.”

That 1969 season was a vintage year in F3. The battles at the front were usually between Peterson (Tecno), Reine Wisell (Chevron) and Schenken’s Brabham, with Emerson Fittipaldi (Lotus) and Howden Ganley (Chevron) coming on strong mid-season. Out of so many races, with wins from Barcelona to Albi, Jarama to Cadwell Park, Tim picks out one at Crystal Palace. “There were six of us all fighting it out: me, Ronnie, Reine, Alan Rollinson, Bev Bond and Roy Pike. Ronnie and I exchanged the lead over and over, but on the lap that mattered I was ahead by a few feet.

“I also did the Marathon de la Route, that 84-hour thrash round the Nürburgring, in a Cologne Ford Capri with Jean-François Piot and Dieter Glemser. A great way to learn the ’Ring, but an utterly mad event. No pitstop could last more than one minute, otherwise you racked up penalties, but the driver could stop out on the track and work on the car himself – except if any one lap took more than 24 minutes in total, you were disqualified. As the cars got more and more worn out, people were leaving the pits with their overalls bulging with brake pads, spanners and bits of wire. We each drove four hours on, eight hours off, and after nearly 60 hours we had a six-lap lead. By then the rear brakes, drums of course, were on the rivets. Changing shoes would’ve taken too long and bust the 24-minute lap limit, so I stopped out on the track, as far away from any marshals as I could, disconnected the rear brakes, and carried on with the fronts only. In the end a head gasket blew.

In the Surtees TS9B-Ford at Brands in 1972. Neither the race nor Schenken’s relationship with the boss went well

Motorsport Images

“Rodney and I agreed we had to go F2 for 1970. Brabham lent us a chassis and we got some money from Castrol to pay for an FVA engine. F2 was fantastic then, because all the F1 drivers did it. You had the likes of Stewart, Rindt, Ickx, Siffert to gauge yourself against. But it was a hard year. I had a couple of podiums, and I qualified second at Zolder and led Jochen Rindt briefly, but we were plagued by mechanical problems. In June Piers [Courage] was killed in the Dutch GP in Frank Williams’ de Tomaso. I took a deep breath, steeled myself, went to see Frank and said I wanted the drive. In fact he put Brian Redman in the car for Brands and Hockenheim, but Brian didn’t start either race, and so he put me in for the Austrian GP at Zeltweg. Frank was incredibly keen, incredibly intense. A wonderful organiser, but he had no technical skills at all: his cars were basically run by the mechanics. He didn’t give me any instructions or guidance. I just got in the thing and drove it. You didn’t have an engineer in those days. You decided yourself if you wanted more or less rollbar, shockers up or down, more or less rear wing. If it was raining you disconnected the rollbar: we thought that was really sophisticated. What Frank was lacking was a Patrick Head. When he and Patrick got together, they were away.

“My second F1 race was three weeks later at Monza, and in Saturday’s practice Rindt was killed. Jochen and I were mates, we’d raced together in F2, but more than that he was a huge hero of mine. I felt the same as when Lex Davison was killed, just confused and all alone. I’m sure other drivers went through the same thing, and that year a lot of guys died. Even so, I didn’t lie awake at night. All drivers have this belief, ‘It’s not going to happen to me’. If you thought any different you couldn’t have got in the car.”

At the end of 1970 Jack Brabham retired, and long-time partner Ron Tauranac bought him out. Graham Hill was signed to drive the new BT34, the twin-radiator “Lobster Claw”, and Tim got a proper F1 ride in the year-old BT33. There were non-championship F1 races in those days, and in the space of seven weeks Tim was fourth in the Race of Champions, fifth in the Questor GP at Ontario, ninth in the Spanish GP and third in the Daily Express Silverstone. “Actually, to start with I didn’t quite grasp F1. Because of the power of the car I was trying to get the engine to do all the work, and I wasn’t carrying my speed into the corners. But in my fourth Grand Prix, at Paul Ricard, it all clicked. I’d qualified 14th, but I passed a lot of people and with six laps to go I’d just taken Jo Siffert for fourth place, and was nosing alongside Emerson Fittipaldi for third, when the engine blew. Two weeks later at Silverstone Ronnie, Emerson and I were all falling over each other for second place, until my gearbox failed.

“Then I got a point at the Nürburgring. I qualified on the fifth row, just getting under 7min 30sec, and Jenks wrote that it was a good effort in the old Brabham. That meant a lot to me, because 10 years earlier I’d been drinking in every word of his stuff working as a clerk in Melbourne, eagerly awaiting copies of Motor Sport off the boat. Two weeks later I got on the podium in Austria, so it was starting to happen.” Tim was the second Australian, after Jack Brabham, to score World Championship points. With Alan Jones and Mark Webber, he is still one of only four.

Jaguar XJC was prone to breaking in 1977

Motorsport Images

“That autumn I heard rumours that Ron Tauranac was thinking about selling Brabham. I didn’t believe it, because I was sure he would have told me, but I tackled him about it, and I was shocked when he said he’d already sold the business to Bernie Ecclestone. I went to see Bernie, and he offered me a two-year contract. I didn’t know much about Bernie, didn’t know what the team would be like under his regime. So I told him I wanted to sign just for one year. Bernie said, ‘I’m not going to employ you for a year and then have you go off and drive for somebody else.’ So I asked Tauranac what he thought I should do. To my surprise Ron, having done the deal with Bernie, was quite scathing about him. He told me to talk to John Surtees, because John wanted to stop driving and just run his F1 team.

“So I went to see Surtees, and he offered me a drive, and I took it. Bad decision. It was the beginning of the end of my F1 career. I don’t know how to talk about Surtees without inviting a shoal of solicitors’ letters, but for me he was absolutely impossible. Mike Hailwood, my team-mate, could cope with it because he’d just turn up, drive the car, and go away. I wanted to work with the team and the mechanics, looking for improvements and ways to get the car right. But John always wanted to do everything himself. He’d say, ‘We’re testing at Goodwood tomorrow’, and I’d arrive early, and John would get in the car and go trudging around and around, and then come in and dictate copious notes to his secretary, who rejoiced in the name of Gloria Dollar. Then he’d go off again, round and round. Testing would stop at 5pm, and at 4.50pm I’d be allowed in the car, set up for John, steering wheel up near my chest, go out and do a time and find the car was the same as it had been before. And the team was short of money. It was just so frustrating. Before then I’d always had a good working relationship with any team I’d driven for, but with Surtees it was almost like war, like driving for someone who was against you. One example: at the British GP I qualified fifth, quicker than Mike, and John said, ‘The times are wrong. I’m going to tell the timekeepers.’ Stupid stuff. There are others who drove for John who have similar stories.

“But fortunately I had sports car racing with Ferrari and F2 rides with Rondel to keep me sane. In the Monza paddock before the Italian GP in 1971, an Italian girl came up and said, ‘If you’re interested in driving for Ferrari, please come down to our truck after practice.’ I thought it was a joke, Emerson or Ronnie winding me up. But in the end I went over and [Ferrari team manager] Peter Schetty was there, very agitated, because Mr Ferrari had been driven over from Maranello and was holed up in a hotel outside the Monza gates, waiting to see me. So off we went and, sitting in the back of this little restaurant, me and Enzo Ferrari, we did a deal there and then. It was for nine long-distance races in the Ferrari 312P. I asked for £2000 a race, and he agreed straight away. And £18,000 was a lot of money then. Howden Ganley and I had just bought a house to share in Maidenhead, and it cost us £7500.

“I was paired with Ronnie, because we were the same size, and we knew each other so well. We started off with a win in the Buenos Aires 1000Kms, and we won the Nürburgring 1000Kms too. We were second at Daytona and Sebring, second at the BOAC Brands and Watkins Glen, third at Monza and Zeltweg – that was after I hit a hare and punctured a tyre.

“At Sebring I nearly hit an aircraft. One third of the width of the main runway was the circuit, two-thirds was an active airstrip. Coming onto the runway a rear brake hose burst, and I slid under the wing of an aircraft revving up for take-off. The only race we didn’t finish was Spa. Ronnie was chasing Brian Redman for the lead, on slicks, when he arrived at Les Combes and there’d been one of those little Spa showers, so he collected the barriers in a big way.

“The night before Daytona Ronnie says, ‘Let’s go for a drive on the beach.’ I’m driving, and we go down the ramp onto the beach in our hire car doing about 70mph, right in front of a police car. They nab us, we haven’t got any ID, so it’s back to the police station and into the cells with the drunks. I suggest they hold me and let Mr Peterson go back to our hotel for our passports. Eventually they agree to that. So Ronnie, being Ronnie, gets into the hire car and rockets off down the road, wheels spinning. They set off after him, can’t catch him, and have to radio ahead and set up a road block to stop him. Half an hour later they bring him back looking very sheepish. Now it’s 2am. So we call Peter Schetty, he gets Bill France out of bed, Big Bill talks to the cops and they let us go, and we’re on the grid bright-eyed and bushy-tailed for the 10am start. We finished second – without a gearbox problem we might have won that one.

“The 312P was quite difficult to drive, a bit nervous with its short wheelbase. In practice Ronnie’d get in and do a blistering time straight off, then I’d get in and do a lot of work to get the balance right, and eventually get down to his time. Then he’d get in again and do exactly the same time he’d done before. All my work hadn’t made the car faster, just easier to drive, and less hard on the tyres. He’d do the time either way. He was just a natural.

“In 1972 Ferrari’s sports car programme was more limited, but I was paired with Carlos Reutemann, and we had a couple of second places. I had my first Le Mans that year with the long-tailed 312P. Carlos and I led ahead of Ickx and Redman from about 10pm until dawn. Then, with everything going well and all the gauges reading normal, a rod let go.

“All this time I was doing F2 as well. I’d got to know Ron Dennis at Brabham – he was Graham’s F1 mechanic and Neil Trundle was mine – and he and Neil set up Rondel Racing, with a couple of borrowed F2 chassis. Even then Ron was all about presentation. Not only were the cars immaculate: the transporter was immaculate too. Ron had two nicknames: Team Briefcase, because he always carried a briefcase, and Team Dream, because he had a dream. He wasn’t going to be just a mechanic, or just have a little F2 outfit. He’d set his sights high, even then.”

Tim also raced a Loos Porsche 935 with Derek Bell at that year’s Silverstone Six Hours

Motorsport Images

Tim did three F2 seasons for Rondel. In 1971, despite various problems, he was fourth in the European Championship, and won the last 1600cc F2 race in Argentina. In 1972, with BT38s and the new 2-litre engines, Rondel over-reached itself with a four-car team, but Tim won at Hockenheim and had a couple of seconds. For 1973 the team ran its own Ray Jessop-designed car, the Motul M1, and Tim scored its only win at the Norisring.

“For ’73 Ron was planning an F1 car. I’d fallen out with Surtees, so I decided to throw in my lot with him. But the money wasn’t there, and the project was sold to Tony Vlassopulo and Ken Grob, and became the Token. Then Ron Tauranac did the Trojan F1 car for Peter Agg, so I got involved with that. It just didn’t work. We went to nine Grands Prix and I really tried hard, but it was always at the back of the grid, and a couple of times we didn’t even qualify. We could never get the back end to grip. Ron told me years later he’d made a fundamental error in the rear suspension, and the aerodynamics were all wrong too. By now I had to accept I’d lost F1, I couldn’t see myself getting back in. I drove once more for Frank Williams in the Iso-Marlboro, at Mosport, and I did Watkins Glen in a Lotus 76, which was a disaster. But I did one or two F2 races for odd people, and I started driving in Group 4 for Georg Loos, which kept me alive.”

Tim did Le Mans for Loos three times, and won the Nürburgring 1000Kms again with Rolf Stommelen and Toine Hezemans. And, driving the monstrous 1000bhp Porsche 917/10, he won Interserie rounds at Zandvoort, the Nürburgring and Hockenheim. “That was a strange car. I was a bit nervous of it at first, but it was amazingly easy to drive. Huge amounts of downforce for its time, lots of grip.

“In September 1976 I was at Monza for the Six Hours. Brigitte was very pregnant, and I was calling home every few hours to check on her. Loos had entered two 934s, but only three drivers turned up, Hezemans, Klaus Ludwig and me. So I shared one car with Toine and the other with Klaus, and I finished first and second in the same race. I flew back to Heathrow that night, rushed to the hospital, and arrived just as my son Guido was born. That was a good day.

“In 1977 I had a clandestine meeting with [BL competitions boss] John Davenport in a pub off the M4, which led to the European Touring Car Championship with Ralph Broad’s V12 XJ Jaguar Coupés. They were prepared to an incredible degree, and very fast, but heavy: they slowed like a train coming into a station. And they kept breaking. I shared with John Fitzpatrick and we took it in turns to be the starting driver: the other never needed to get changed. In the TT at Silverstone I spun when leading, and later a stub axle broke and I hit the bank at Becketts. That car needed more money and more time.

Winning the Nurburgring 1000kms in 1972 with close pal Ronnie Peterson

Motorsport Images

“Meanwhile I’d gone into business with Howden Ganley, who’d been a mate ever since F3, and set up Tiga Racing Cars. But we soon found we didn’t really mesh in the car building operation, so we decided I should set up a racing team. John Hogan of Marlboro had a young lad called Andrea de Cesaris who wanted to do F3. We tidied up a corner of the workshop, had a meeting with Hogey and Andrea, and then Hogey said, ‘I think this’ll work, now what’s it going to cost?’ Quick as a flash I said, ‘Our accountant is just finalising the figures, I’ll get back to you.’ Then I said to Howden, ‘What the hell do we do now?’ In the end I rang Derek Bennett and asked what Chevron charged for a year, and I rang Max [Mosley] at March and asked him what he charged – which was rather more! – and I split the difference and called Hogan. ‘We’ve just got the figures through from our accountant. It’ll be £55,000.’ ‘Fine’, says Hogey, ‘I’ll draw up a contract.’

“Howden kept Tiga going for 15 years, and they produced around 400 race cars to various different formulae. In Team Tiga I ran F3, FF, FF2000, Sports 2000, drivers like James Weaver, Mike Thackwell, Stefan Johansson, even Eddie Jordan on one occasion. Eje Elgh drove an F2 programme with us. It was hard work, 5am to 10pm, seven days a week, a staff of up to 20 people. And in the English climate I was fed up with seeing my children’s noses running down their faces. I was hankering after Australia. In 1982 we moved to San Diego for two years, running John Fitzpatrick’s IMSA race team, but then the CAMS job came up at the end of ’83, and I took it. It was a shock to my system – I’d never worked in administration before – and Australian racing wasn’t very consistently run then. I tried to feed in all I’d learned in 15 years in Europe, and it was difficult at first, but I hung in there. And I still, after all this time, find it fascinating. Motor racing keeps evolving, every race something different happens. It’s a huge challenge the whole time. I wouldn’t know what to do if I stopped.”

Tim has served as Clerk of the Course for every Australian F1 GP meeting, starting in Adelaide in 1985. So this year’s season-opener at Albert Park was his 25th in that role. In 2008 he was brought in as Clerk of the Course for F1’s first night race at Singapore, which also involved training some 700 local officials with no previous experience. CAMS was one of the first national bodies to have a structured licensing system for officials, with proper training and grading. Tim’s duties take him to every major race meeting in Australia, including the ultra-competitive V8 Supercar series, which also goes to New Zealand and Bahrain. “If you want to do the job properly, you can never be everybody’s friend – particularly among the hard-fighting Supercar crowd. All you can hope to do is earn their respect.” With a reputation of being tough but fair, he seems to have achieved that.

Some say Tim Schenken was unlucky, that his career, which at one stage promised to go to the very top, was ruined by that wrong turning at the end of an impressive first full F1 season. “I don’t feel any regret at all. I never complain about anything I’ve had out of my life in motor sport. I’m still here, and I look at the grids from those days and it’s frightening to see who isn’t around to tell the tale. My full-time involvement with the sport I love has lasted my entire adult life. That’s not unlucky. That’s lucky.”

What do racers do when they stop racing? All that competitive edge has to go somewhere. Many attack the world of business with the same will to win that they displayed in the cockpit. Others find ways to stay close to the sport, running a team, or even building racing cars. A handful join the media circus as a commentator or pundit.

A few, inevitably, stand on the sidelines, complaining that things ain’t what they used to be in their day.

And one or two acknowledge what they got out of the sport by putting something back. Tim Schenken is one of those. His professional racing career included almost 40 F1 starts, and spells as works driver for Ferrari and Jaguar. He also went the team manager route, helping several young drivers on their way, and he became a race car manufacturer as well. But in 1984 he decided to return to Melbourne with his family and joined the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport, which governs and administers the country’s racing. Today, 25 years on, he’s still there, as Director of Racing Operations.

Tim and Brigitte, his wife of 35 years, live within walking distance of Albert Park, in a stylish modern house near the sea. At The Stokehouse, a beach restaurant full of Melbourne’s beautiful young things, we eat seared scallops, red snapper and cuttlefish. Tim is 65 now, tall and rangy, thinner on top but apparently still the same weight as the skinny, ambitious would-be racer who, 44 years ago, landed in England with empty pockets.

His chemical engineer father emigrated to Australia from Germany in the 1920s, and married a politician’s daughter. Growing up in Melbourne, Tim was fascinated by the hillclimb special raced by the father of a school friend. By 13 he’d built himself a crude go-kart out of a bedframe from the local dump, powered by a scrap Villiers engine, and roared around the local dirt roads. When he was old enough to drive legally he’d borrow his mother’s Simca Aronde, saying he was going to a barbie with some mates, and then go on a club rally.

“One Sunday morning at Calder there was a straight-line sprint, which didn’t require a competition licence, but in the afternoon they had proper circuit races, which did. Of course I didn’t have a licence, but when the cars were lining up at the paddock gate to go out for practice I joined the queue in the Simca, and nobody checked, so I went out and thrashed round. They put up the list of times and to my amazement I saw they’d given me a grid position for the race. So I did it in my mum’s Aronde, and I won a trophy. I hid it in the roof of the garage. Years later, when my parents were selling the house and I was racing in England, I got my brother to go in and retrieve it.”

When Tim did get his CAMS licence he bought a race-prepared Austin A30 with Sprite engine and alloy crossflow head. He got a clerical job in the Melbourne BMC dealer, so he could scoop up any broken bits that had been changed under warranty and repair them for his racer. “Every lunchtime I would walk two blocks to the overseas magazine store to see if anything had come in off the boat: the green one, Motor Sport, the red one, Autosport, or the yellow one, Motor Racing. I read them cover to cover, taught myself all about European racing.

“The A30 wasn’t very competitive, but in 1964 Rocky Tresise, an up-and-coming Melbourne driver, was selling his Lotus 18 because he was joining Lex Davison’s team. I borrowed the money from my dad to get it. Now I was in a proper racing car, and I started attracting a bit of attention at Calder, Winton, Tarrawingee, Sandown Park. I also did hillclimbs in a friend’s JAP-powered special. It was so small and powerful for its weight I was able to beat all the local 1100 Coopers, and I managed to win the Australian Hillclimb Championship.

“Then, out of the blue, Lex Davison called. He was a major figure, of course, and a real hero of mine. He told me he was going to retire, and Rocky Tresise was going to take over his big single-seaters. He’d watched me in the Lotus 18, and he wanted to put me in his Elfin. It was unbelievable for me.”

Davison, four times Australian Grand Prix winner in HWM, Ferrari and Cooper-Climax, had been a cornerstone of Australian motor racing for two decades. Barely a week after his conversation with Tim, Davison’s Ecurie Australie was running at Sandown Park: 41-year-old Lex in an ex-Denny Hulme Brabham, 21-year-old Rocky in an ex-Bruce McLaren Cooper.

During Saturday practice the Brabham crashed heavily going onto the back straight, and Davison died a few hours later.

“Because of Lex’s status in Australia, there were hundreds of people at his funeral in St Patrick’s Cathedral, including Jack Brabham and Bruce McLaren. I’d never been to a funeral before, and it was dreadful. On the coffin was a chequered flag and his helmet and gloves. I didn’t know anyone, I just hung around on the edge of it, very muddled about it all.”

The following weekend the team was entered for the Australian GP at Longford, and Rocky Tresise persuaded Lex’s wife Diana that he should still run the Cooper, as a tribute to Lex. He made a bad start, and was carving through the field at the end of the first lap when he got two wheels on the grass. The Cooper went out of control, through a fence and end-over-end. Tresise and a photographer were killed.

“It was terrible, Lex and Rocky dying on consecutive weekends. It just stunned everybody. The thing was, the weekend after Rocky’s crash I was due to run for the first time under the Ecurie Australie banner, at Calder in my Lotus 18. The newspapers got hold of it and were speculating whether it would be three fatal crashes in three weekends. I went to see Diana Davison, and she pleaded with me not to race at Calder. I was under a lot of pressure not to drive; I felt I couldn’t talk to my parents about it, but all I wanted to do was go racing. I was a very confused boy.” Tim did race the Lotus at Calder, but entered under his own name. The transmission broke on the startline.

“I knew I was going to have to get myself to Europe, so I left the Lotus with my father to sell, and my friend Brian Andrews and I scraped together the fares for a slow boat to Southampton, via Papua New Guinea, Port Said, Suez, Athens and Naples. Included in the deal was the bus ride from Southampton to Earl’s Court, and two weeks in a bedsit in Kangaroo Valley. When we arrived, in November 1965, the first thing I did was find the Autosport offices in Paddington, introduce myself to the assistant editor, Paddy McNally, and persuade him to put a snippet in the magazine saying that the Australian Hillclimb Champion had arrived in the UK and was open to offers. I waited for the phone to ring, but it must have been a slow week…

“Brian and I persuaded Graham Warner at the Chequered Flag in Chiswick to take us on as mechanics in the servicing bay. Brian was a qualified mechanic, I certainly wasn’t, but he carried me: I did the oil changes and the simple stuff, and he helped me with anything more complicated. At weekends I went to races, got to know people, Nick Syrett at the BRSCC, Grahame White at the BARC. Then at the Flag somebody traded in a twin-cam Anglia race car that had been rolled. I talked Graham into letting me rebuild it. He provided the parts, I did the work in my spare time, and during 1966 I learned the English circuits in that.

“Chas Beattie ran the Flag’s race team, the F3 Brabhams which Chris Irwin and Roger Mac drove, and the 7-litre Cobra, working out of a railway arch under Stamford Brook station. Every time a District Line train went over, paint used to fall from the roof. When the money from the 18 came through I bought an ex-racing school Lotus 22, with tin wheels and rubber suspension bushes. Chas let me use old rose joints and shockers out of the rubbish bin, and I got it sorted and did F3 with it in 1967. I took it around in an old laundry van, with a plywood box on the back where the nose stuck out. Then at Crystal Palace one of my welds broke on the front suspension. I never was much good at welding. I hit the sleepers, and that was the end of the Lotus.

“Formula Ford was just getting off the ground, and Selwyn Hayward of Merlyn was looking for somebody to run a semi-works FF car. He’d seen me pedalling the old Lotus, so he asked me to a test at Brands, and I ended up with a loaned Merlyn chassis and an engine from Chris Steele. Chas had set up on his own now, in a shed by the old Aston Martin works at Feltham, and I used a corner of it to prepare the car. Chas was a huge help. He taught me that it’s what you do before you get to the circuit that matters. Get all the wheels pointing in the right direction, get all the corner weights right. Then, if there’s a handling issue when you get there, it’s not because of the basic set-up.”

The impact that Tim made on the 1968 racing scene was devastating. Straight away he dominated Formula Ford so absolutely that by April he’d been offered a competitive F3 seat by Rodney Bloor, who ran a Chevron under the banner of his Manchester business, Sports Motors. “I’d do four races in a weekend: F3 and FF on Saturday at Oulton, F3 and FF on Sunday at Snetterton. In FF I had the right car and the right engine, always made sure my gear ratios were spot-on for each circuit. With the Chevron there were some handling problems to start with, but once I got my confidence with it I was away.” In that hectic season Tim clocked up 36 victories, and won both the British Formula Ford Championship and the British Formula 3 Championship – a feat never achieved before or since. And, inevitably, he won the season’s top Grovewood Award. “I suppose I was the dog’s bollocks then. We did some European FF races, too. Went to Spa, the old 8.7-mile road circuit, for a support race at the Belgian GP. You only needed to brake for La Source and at the top of the hill, Les Combes, and maybe a touch at Stavelot. So, pretty much flat for over seven miles, pulling 132mph down the hill.

“I also did the Monza and Spa 1000Kms races. John Raeburn, another Aussie who worked at the Flag, got me a ride with him in Andy Cox’s old GT40. At Spa the ride height was all wrong, and through the fast bits you could turn the wheel and nothing happened, like being in a speedboat. It frightened the life out of me. Then for the race it rained. Real Spa rain. We only had slicks, we couldn’t afford wets. John started, and at the end of lap one Jacky Ickx arrived in a plume of spray, down the hill, up Eau Rouge and out of sight before anybody else appeared. Then everybody else came through, and after a pause John came gingerly round La Source on his slicks. We hung the board out for him, he gave us a little wave – and spun, clouted the bridge parapet, put it in the ditch. I’ve never been so relieved in all my life.

“For 1969 Rodney ran what was effectively the works F3 Brabham, the new BT28. It was painted red and black, because we had a little money from Guards cigarettes. The works team consisted of an old Ford Zephyr with the back seat and rear bulkhead removed, four wheels and a nosecone in the back, spare engine and gear ratios in the boot, towing an open trailer with the car on it. That’s how we went around Europe, me driving, my mechanic John Schofield in the passenger seat, terrified because we always towed at 90mph. We thought we were pretty professional in F3 then. Today it would seem like amateur hour, but with the narrow power band on those little 1000cc screamers, gear ratios were crucial. At Brands Hatch, for qualifying you’d put in an extra second gear in the first gear position just to suit Druids, but then you’d have to change it to a normal first for the race to make sure you could get off the line. So you’d qualify using all four gears, and then race only using three gears. You’d keep all your secrets, never tell any of your rivals what you were doing. Then at Brands this lanky blond Swedish kid came up and asked me what ratios I was using, and I don’t know why, but I told him. That was Ronnie Peterson. We were friends from then on.”

That 1969 season was a vintage year in F3. The battles at the front were usually between Peterson (Tecno), Reine Wisell (Chevron) and Schenken’s Brabham, with Emerson Fittipaldi (Lotus) and Howden Ganley (Chevron) coming on strong mid-season. Out of so many races, with wins from Barcelona to Albi, Jarama to Cadwell Park, Tim picks out one at Crystal Palace. “There were six of us all fighting it out: me, Ronnie, Reine, Alan Rollinson, Bev Bond and Roy Pike. Ronnie and I exchanged the lead over and over, but on the lap that mattered I was ahead by a few feet.

“I also did the Marathon de la Route, that 84-hour thrash round the Nürburgring, in a Cologne Ford Capri with Jean-François Piot and Dieter Glemser. A great way to learn the ’Ring, but an utterly mad event. No pitstop could last more than one minute, otherwise you racked up penalties, but the driver could stop out on the track and work on the car himself – except if any one lap took more than 24 minutes in total, you were disqualified. As the cars got more and more worn out, people were leaving the pits with their overalls bulging with brake pads, spanners and bits of wire. We each drove four hours on, eight hours off, and after nearly 60 hours we had a six-lap lead. By then the rear brakes, drums of course, were on the rivets. Changing shoes would’ve taken too long and bust the 24-minute lap limit, so I stopped out on the track, as far away from any marshals as I could, disconnected the rear brakes, and carried on with the fronts only. In the end a head gasket blew.

“Rodney and I agreed we had to go F2 for 1970. Brabham lent us a chassis and we got some money from Castrol to pay for an FVA engine. F2 was fantastic then, because all the F1 drivers did it. You had the likes of Stewart, Rindt, Ickx, Siffert to gauge yourself against. But it was a hard year. I had a couple of podiums, and I qualified second at Zolder and led Jochen Rindt briefly, but we were plagued by mechanical problems. In June Piers [Courage] was killed in the Dutch GP in Frank Williams’ de Tomaso. I took a deep breath, steeled myself, went to see Frank and said I wanted the drive. In fact he put Brian Redman in the car for Brands and Hockenheim, but Brian didn’t start either race, and so he put me in for the Austrian GP at Zeltweg. Frank was incredibly keen, incredibly intense. A wonderful organiser, but he had no technical skills at all: his cars were basically run by the mechanics. He didn’t give me any instructions or guidance. I just got in the thing and drove it. You didn’t have an engineer in those days. You decided yourself if you wanted more or less rollbar, shockers up or down, more or less rear wing. If it was raining you disconnected the rollbar: we thought that was really sophisticated. What Frank was lacking was a Patrick Head. When he and Patrick got together, they were away.

“My second F1 race was three weeks later at Monza, and in Saturday’s practice Rindt was killed. Jochen and I were mates, we’d raced together in F2, but more than that he was a huge hero of mine. I felt the same as when Lex Davison was killed, just confused and all alone. I’m sure other drivers went through the same thing, and that year a lot of guys died. Even so, I didn’t lie awake at night. All drivers have this belief, ‘It’s not going to happen to me’. If you thought any different you couldn’t have got in the car.”

At the end of 1970 Jack Brabham retired, and long-time partner Ron Tauranac bought him out. Graham Hill was signed to drive the new BT34, the twin-radiator “Lobster Claw”, and Tim got a proper F1 ride in the year-old BT33. There were non-championship F1 races in those days, and in the space of seven weeks Tim was fourth in the Race of Champions, fifth in the Questor GP at Ontario, ninth in the Spanish GP and third in the Daily Express Silverstone. “Actually, to start with I didn’t quite grasp F1. Because of the power of the car I was trying to get the engine to do all the work, and I wasn’t carrying my speed into the corners. But in my fourth Grand Prix, at Paul Ricard, it all clicked. I’d qualified 14th, but I passed a lot of people and with six laps to go I’d just taken Jo Siffert for fourth place, and was nosing alongside Emerson Fittipaldi for third, when the engine blew. Two weeks later at Silverstone Ronnie, Emerson and I were all falling over each other for second place, until my gearbox failed.

“Then I got a point at the Nürburgring. I qualified on the fifth row, just getting under 7min 30sec, and Jenks wrote that it was a good effort in the old Brabham. That meant a lot to me, because 10 years earlier I’d been drinking in every word of his stuff working as a clerk in Melbourne, eagerly awaiting copies of Motor Sport off the boat. Two weeks later I got on the podium in Austria, so it was starting to happen.” Tim was the second Australian, after Jack Brabham, to score World Championship points. With Alan Jones and Mark Webber, he is still one of only four.

“That autumn I heard rumours that Ron Tauranac was thinking about selling Brabham. I didn’t believe it, because I was sure he would have told me, but I tackled him about it, and I was shocked when he said he’d already sold the business to Bernie Ecclestone. I went to see Bernie, and he offered me a two-year contract. I didn’t know much about Bernie, didn’t know what the team would be like under his regime. So I told him I wanted to sign just for one year. Bernie said, ‘I’m not going to employ you for a year and then have you go off and drive for somebody else.’ So I asked Tauranac what he thought I should do. To my surprise Ron, having done the deal with Bernie, was quite scathing about him. He told me to talk to John Surtees, because John wanted to stop driving and just run his F1 team.

“So I went to see Surtees, and he offered me a drive, and I took it. Bad decision. It was the beginning of the end of my F1 career. I don’t know how to talk about Surtees without inviting a shoal of solicitors’ letters, but for me he was absolutely impossible. Mike Hailwood, my team-mate, could cope with it because he’d just turn up, drive the car, and go away. I wanted to work with the team and the mechanics, looking for improvements and ways to get the car right. But John always wanted to do everything himself. He’d say, ‘We’re testing at Goodwood tomorrow’, and I’d arrive early, and John would get in the car and go trudging around and around, and then come in and dictate copious notes to his secretary, who rejoiced in the name of Gloria Dollar. Then he’d go off again, round and round. Testing would stop at 5pm, and at 4.50pm I’d be allowed in the car, set up for John, steering wheel up near my chest, go out and do a time and find the car was the same as it had been before. And the team was short of money. It was just so frustrating. Before then I’d always had a good working relationship with any team I’d driven for, but with Surtees it was almost like war, like driving for someone who was against you. One example: at the British GP I qualified fifth, quicker than Mike, and John said, ‘The times are wrong. I’m going to tell the timekeepers.’ Stupid stuff. There are others who drove for John who have similar stories.

“But fortunately I had sports car racing with Ferrari and F2 rides with Rondel to keep me sane. In the Monza paddock before the Italian GP in 1971, an Italian girl came up and said, ‘If you’re interested in driving for Ferrari, please come down to our truck after practice.’ I thought it was a joke, Emerson or Ronnie winding me up. But in the end I went over and [Ferrari team manager] Peter Schetty was there, very agitated, because Mr Ferrari had been driven over from Maranello and was holed up in a hotel outside the Monza gates, waiting to see me. So off we went and, sitting in the back of this little restaurant, me and Enzo Ferrari, we did a deal there and then. It was for nine long-distance races in the Ferrari 312P. I asked for £2000 a race, and he agreed straight away. And £18,000 was a lot of money then. Howden Ganley and I had just bought a house to share in Maidenhead, and it cost us £7500.

“I was paired with Ronnie, because we were the same size, and we knew each other so well. We started off with a win in the Buenos Aires 1000Kms, and we won the Nürburgring 1000Kms too. We were second at Daytona and Sebring, second at the BOAC Brands and Watkins Glen, third at Monza and Zeltweg – that was after I hit a hare and punctured a tyre.

“At Sebring I nearly hit an aircraft. One third of the width of the main runway was the circuit, two-thirds was an active airstrip. Coming onto the runway a rear brake hose burst, and I slid under the wing of an aircraft revving up for take-off. The only race we didn’t finish was Spa. Ronnie was chasing Brian Redman for the lead, on slicks, when he arrived at Les Combes and there’d been one of those little Spa showers, so he collected the barriers in a big way.

“The night before Daytona Ronnie says, ‘Let’s go for a drive on the beach.’ I’m driving, and we go down the ramp onto the beach in our hire car doing about 70mph, right in front of a police car. They nab us, we haven’t got any ID, so it’s back to the police station and into the cells with the drunks. I suggest they hold me and let Mr Peterson go back to our hotel for our passports. Eventually they agree to that. So Ronnie, being Ronnie, gets into the hire car and rockets off down the road, wheels spinning. They set off after him, can’t catch him, and have to radio ahead and set up a road block to stop him. Half an hour later they bring him back looking very sheepish. Now it’s 2am. So we call Peter Schetty, he gets Bill France out of bed, Big Bill talks to the cops and they let us go, and we’re on the grid bright-eyed and bushy-tailed for the 10am start. We finished second – without a gearbox problem we might have won that one.

“The 312P was quite difficult to drive, a bit nervous with its short wheelbase. In practice Ronnie’d get in and do a blistering time straight off, then I’d get in and do a lot of work to get the balance right, and eventually get down to his time. Then he’d get in again and do exactly the same time he’d done before. All my work hadn’t made the car faster, just easier to drive, and less hard on the tyres. He’d do the time either way. He was just a natural.

“In 1972 Ferrari’s sports car programme was more limited, but I was paired with Carlos Reutemann, and we had a couple of second places. I had my first Le Mans that year with the long-tailed 312P. Carlos and I led ahead of Ickx and Redman from about 10pm until dawn. Then, with everything going well and all the gauges reading normal, a rod let go.

“All this time I was doing F2 as well. I’d got to know Ron Dennis at Brabham – he was Graham’s F1 mechanic and Neil Trundle was mine – and he and Neil set up Rondel Racing, with a couple of borrowed F2 chassis. Even then Ron was all about presentation. Not only were the cars immaculate: the transporter was immaculate too. Ron had two nicknames: Team Briefcase, because he always carried a briefcase, and Team Dream, because he had a dream. He wasn’t going to be just a mechanic, or just have a little F2 outfit. He’d set his sights high, even then.”

Tim did three F2 seasons for Rondel. In 1971, despite various problems, he was fourth in the European Championship, and won the last 1600cc F2 race in Argentina. In 1972, with BT38s and the new 2-litre engines, Rondel over-reached itself with a four-car team, but Tim won at Hockenheim and had a couple of seconds. For 1973 the team ran its own Ray Jessop-designed car, the Motul M1, and Tim scored its only win at the Norisring.

“For ’73 Ron was planning an F1 car. I’d fallen out with Surtees, so I decided to throw in my lot with him. But the money wasn’t there, and the project was sold to Tony Vlassopulo and Ken Grob, and became the Token. Then Ron Tauranac did the Trojan F1 car for Peter Agg, so I got involved with that. It just didn’t work. We went to nine Grands Prix and I really tried hard, but it was always at the back of the grid, and a couple of times we didn’t even qualify. We could never get the back end to grip. Ron told me years later he’d made a fundamental error in the rear suspension, and the aerodynamics were all wrong too. By now I had to accept I’d lost F1, I couldn’t see myself getting back in. I drove once more for Frank Williams in the Iso-Marlboro, at Mosport, and I did Watkins Glen in a Lotus 76, which was a disaster. But I did one or two F2 races for odd people, and I started driving in Group 4 for Georg Loos, which kept me alive.”

Tim did Le Mans for Loos three times, and won the Nürburgring 1000Kms again with Rolf Stommelen and Toine Hezemans. And, driving the monstrous 1000bhp Porsche 917/10, he won Interserie rounds at Zandvoort, the Nürburgring and Hockenheim. “That was a strange car. I was a bit nervous of it at first, but it was amazingly easy to drive. Huge amounts of downforce for its time, lots of grip.

“In September 1976 I was at Monza for the Six Hours. Brigitte was very pregnant, and I was calling home every few hours to check on her. Loos had entered two 934s, but only three drivers turned up, Hezemans, Klaus Ludwig and me. So I shared one car with Toine and the other with Klaus, and I finished first and second in the same race. I flew back to Heathrow that night, rushed to the hospital, and arrived just as my son Guido was born. That was a good day.

“In 1977 I had a clandestine meeting with [BL competitions boss] John Davenport in a pub off the M4, which led to the European Touring Car Championship with Ralph Broad’s V12 XJ Jaguar Coupés. They were prepared to an incredible degree, and very fast, but heavy: they slowed like a train coming into a station. And they kept breaking. I shared with John Fitzpatrick and we took it in turns to be the starting driver: the other never needed to get changed. In the TT at Silverstone I spun when leading, and later a stub axle broke and I hit the bank at Becketts. That car needed more money and more time.

“Meanwhile I’d gone into business with Howden Ganley, who’d been a mate ever since F3, and set up Tiga Racing Cars. But we soon found we didn’t really mesh in the car building operation, so we decided I should set up a racing team. John Hogan of Marlboro had a young lad called Andrea de Cesaris who wanted to do F3. We tidied up a corner of the workshop, had a meeting with Hogey and Andrea, and then Hogey said, ‘I think this’ll work, now what’s it going to cost?’ Quick as a flash I said, ‘Our accountant is just finalising the figures, I’ll get back to you.’ Then I said to Howden, ‘What the hell do we do now?’ In the end I rang Derek Bennett and asked what Chevron charged for a year, and I rang Max [Mosley] at March and asked him what he charged – which was rather more! – and I split the difference and called Hogan. ‘We’ve just got the figures through from our accountant. It’ll be £55,000.’ ‘Fine’, says Hogey, ‘I’ll draw up a contract.’

“Howden kept Tiga going for 15 years, and they produced around 400 race cars to various different formulae. In Team Tiga I ran F3, FF, FF2000, Sports 2000, drivers like James Weaver, Mike Thackwell, Stefan Johansson, even Eddie Jordan on one occasion. Eje Elgh drove an F2 programme with us. It was hard work, 5am to 10pm, seven days a week, a staff of up to 20 people. And in the English climate I was fed up with seeing my children’s noses running down their faces. I was hankering after Australia. In 1982 we moved to San Diego for two years, running John Fitzpatrick’s IMSA race team, but then the CAMS job came up at the end of ’83, and I took it. It was a shock to my system – I’d never worked in administration before – and Australian racing wasn’t very consistently run then. I tried to feed in all I’d learned in 15 years in Europe, and it was difficult at first, but I hung in there. And I still, after all this time, find it fascinating. Motor racing keeps evolving, every race something different happens. It’s a huge challenge the whole time. I wouldn’t know what to do if I stopped.”

Tim has served as Clerk of the Course for every Australian F1 GP meeting, starting in Adelaide in 1985. So this year’s season-opener at Albert Park was his 25th in that role. In 2008 he was brought in as Clerk of the Course for F1’s first night race at Singapore, which also involved training some 700 local officials with no previous experience. CAMS was one of the first national bodies to have a structured licensing system for officials, with proper training and grading. Tim’s duties take him to every major race meeting in Australia, including the ultra-competitive V8 Supercar series, which also goes to New Zealand and Bahrain. “If you want to do the job properly, you can never be everybody’s friend – particularly among the hard-fighting Supercar crowd. All you can hope to do is earn their respect.” With a reputation of being tough but fair, he seems to have achieved that.

Some say Tim Schenken was unlucky, that his career, which at one stage promised to go to the very top, was ruined by that wrong turning at the end of an impressive first full F1 season. “I don’t feel any regret at all. I never complain about anything I’ve had out of my life in motor sport. I’m still here, and I look at the grids from those days and it’s frightening to see who isn’t around to tell the tale. My full-time involvement with the sport I love has lasted my entire adult life. That’s not unlucky. That’s lucky.”