“It was a close-run thing, though,” recalls Pilbeam. “I was stood next to the car after the race when I noticed my feet were wet. A stone had gone through a radiator.”

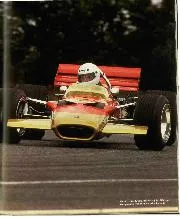

Donington Park, with its sweeps and plunges, does a passable impression of the much-missed old Kyalami. My ‘Beltoise’, though, needs a lot of work. Even so, what strikes me immediately about P201/02 is how many options it gives you. That sonorous V12 pulls away from as low as 1500rpm and will happily short-shift from 6500 on. Which is handy because I’m having my usual early stirrings with an unfamiliar gearbox. The P161 five-speeder has no detent spring and I’m vaulting over the gate and catching the corner between third and dogleg first. I’m still wrestling with the best method of cog-swappery when Justin Law’s Bud Light Jag almost blows me off the track.

Plan B: third for the Esses – we’re on the short circuit – and fourth everywhere else. It works a treat and frees up my tiny journalistic brain to concentrate on lines and braking points – they’re mine and I’m sticking to them – and that fantastic sound. Exiting Coppice faster each time I eventually see 10,000rpm in fourth (9,500 in top on my last lap) as I pass under the Dunlop Bridge. And to think that, like Nigel Tufnell’s custom-built Marshall amp, it will go to 11.

Geoff Johnson’s P142 – originally a two-valver designed for sports cars – is renowned for its smooth delivery. But is it too linear? There’s none of that DFV kick out of corners or top-end grunt at the end of straights. Current driver (and preparer) Rob Hall reckons this 1968 design, albeit reworked by Aubrey Woods – four-valve heads, inlets to the inside of the vee – delivers around 420bhp at a safe 10,500rpm. That’s 50 down on a period DFV, albeit with a few hundred revs still to go. But just as telling is the packaging: this V12 is longer, taller and heavier by a full 80lb than its Cosworth rival. Yet it’s not stiff enough to act as a stressed member and is supported by an A-frame. It needed more fuel too: a tanked-up Lotus 72 carried 40 gallons, P201 had room for 47.

Bob Evans pressured by Depailler at Austria ’75

Grand Prix Photo

“You can feel that weight,” says Hall. “But you can work with it. You can chuck it in on the brakes, which are excellent, and catch that pendulum effect on the way out. The steering is very light; Beltoise used to drive with one arm, basically [his left was badly injured in a 1964 crash at Reims].”

Yeah well, I’ve got two left feet, which is why I leave the scruff-of-the-neck stuff to the experts. I’m instead left with (tinnitus-assisted) memories of a silky machine that takes you to extremely high levels of performance with the minimum of fuss. But then I’m not trying to match a Lauda pole. Beltoise had his arm full.

BRM’s 1974 went into steady decline after the dizzy heights of high-altitude Kyalami. The Belgian GP at Nivelles wasn’t too bad – Beltoise qualified seventh and finished fifth – but there would be no more point scores as the retirements and non-classifications began to rack up: engine, gearbox, ancillary drive belt, engine, electrics.

“The basic problem was that money was tight,” says Pilbeam. “The cars were built okay, but after South Africa we had a lot of blowups and the team was having to reclaim blocks, weld and patch stuff that should have been thrown away. The engine wasn’t bad – at its best. As for the car, I wasn’t happy with its radiator installation and I would’ve liked to tidy up the rear end…”