Andy Tilley was Mika’s engineer that year: “He was really easy to work with, but not very forthcoming technically. But Mika was one of those drivers where if you made the car better, he’d go quicker. He got on with the job and didn’t complain.

“We were always very limited on things like tyres for qualifying and engine mileage. But one of the great things about Mika was that over one lap, he’d do the job.”

Mika dragged the overweight 102D into the points in Mexico, but by Monaco both drivers were equipped with the new 107. Derived from a Leyton House design, it represented a massive leap forward. Suddenly For 1992, the team lined up Ford HB engines. Benetton and Jordan had demonstrated the unit’s potential, and with a new chassis there was cause for optimism. However, Mika had Johnny had to make do with a hack 102D at the start of the season.

Andy Tilley was Mika’s engineer that year: “He was really easy to work with, but not very forthcoming technically. But Mika was one of those drivers where if you made the car better, he’d go quicker. He got on with the job and didn’t complain.

“We were always very limited on things like tyres for qualifying and engine mileage. But one of the great things about Mika was that over one lap, he’d do the job.”

Mika dragged the overweight 102D into the points in Mexico, but by Monaco both drivers were equipped with the new 107. Derived from a Leyton House design, it represented a massive leap forward. Suddenly Häkkinen was regularly on the fringes of the top 10 in qualifying, and threatening to score points. Fourth in France was followed by sixth at Silverstone, fourth in Hungary, sixth in Belgium and fifth in Portugal.

New Lotus 107 made its debut in Monaco, 1992

Grand Prix Photo

But Collins was still frustrated by his young ace. After Mika had lost places late in the British Grand Prix, Peter was angered when he saw photos showing the Finn’s head leaning over. He also faded at Spa.

The ongoing debate led to some fun, as Tilley recalls: “The mechanics lined his kit bag and trainers with lead wheel weights, because they didn’t think he was doing enough training!”

“People say that Lotus was a joke in its last few years, but I’m sorry, it wasn’t. In 1992 we were fifth in the championship.”

Collins: “Mika was very good at bringing the car home, but the results could have been a lot, lot better. At Suzuka, due I think to being tired, he suddenly started over-revving the engine on downchanges. We lost a sure third place in that race. If he had been on the podium it would have made a huge difference to what we could have got from Japanese sponsors the following year.”

Häkkinen was also frustrated at times, as Coton recalls: “It became a bit difficult in the second year because Mika was progressing rapidly with the talent he had. The team couldn’t progress the same way because of a lack of finance. Every driver wants more, but Mika is a clever guy. He understood the situation, and what he did was to do the maximum with what he had. You learn so much as a young driver to prepare yourself for a better team later on.”

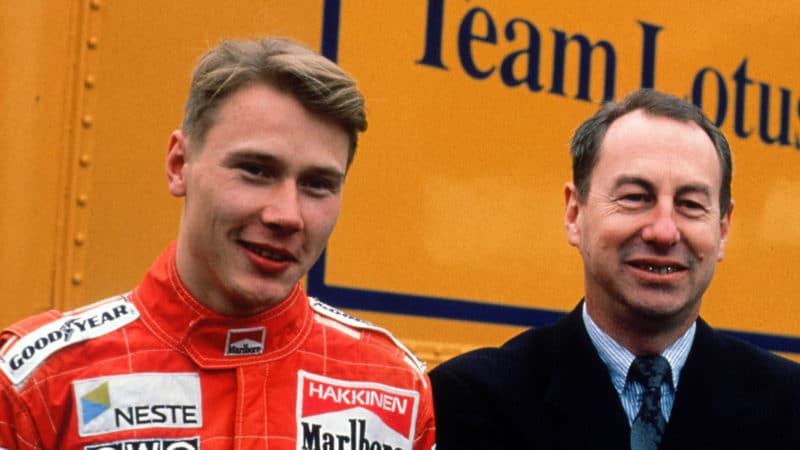

Despite some frustrations, Collins took up his option on Häkkinen’s services for 1993 at Spa, and added another for ‘94. However, late in the year it emerged that Frank Williams was interested in Mika as a replacement for Nigel Mansell. That led to some friction between Collins and Rosberg, and after Frank eventually backed off, Ron Dennis threw his hat into the ring. A messy dispute developed, which was ultimately resolved in McLaren’s favour by the Contract Recognition Board in Geneva. The Häkkinen/Lotus story was over.