As the programme revealed, nor was it only in regard to circuit design that the attitudes were somewhat different then.

“The race goes on. Motor racing must have its dangers, and though every precaution is taken, and though the drivers competing today are the most skilful in the world, there may be accidents. It is a tradition of grand prix racing that whatever happens the race shall go on.

“Pass, Friend. The French were the pioneers of motor racing, and ever since it has been a tradition to use their rule-of-the-road. Therefore, overtaking drivers should pull over to the left-hand side of the road.

“Smoking Permitted. Grand Prix drivers do not normally have to undergo strict physical training. Moderation in eating, drinking and smoking is sufficient, for motor racing is a test of brain rather than brawn.”

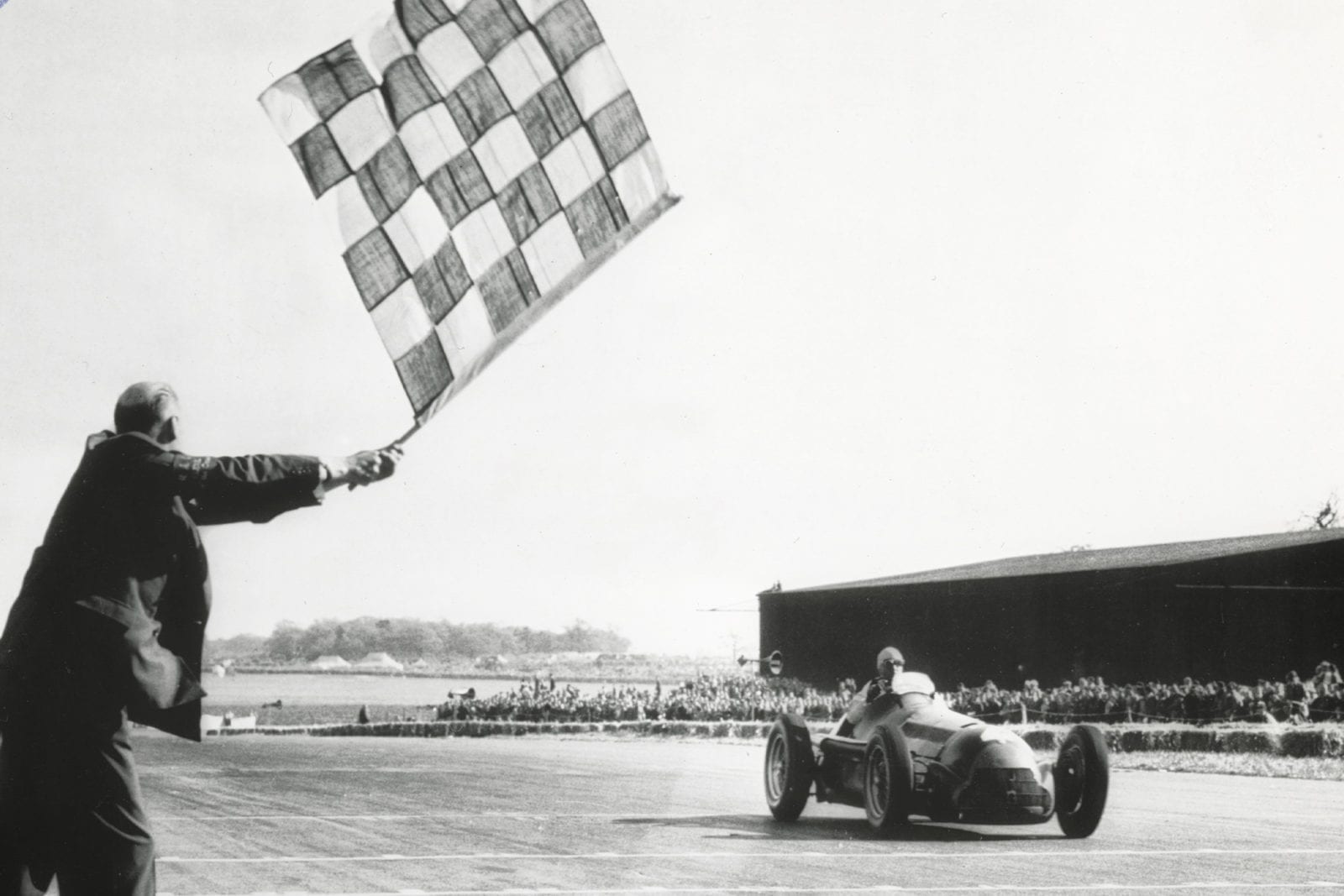

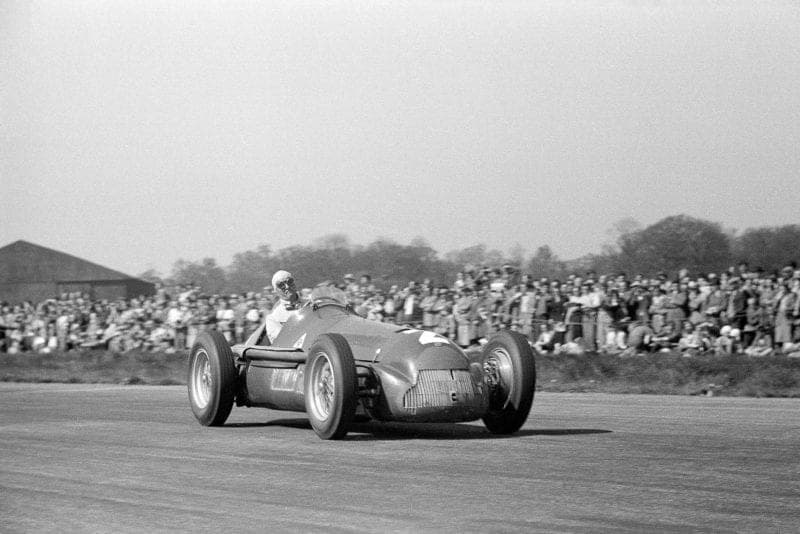

There was also a note of regret. Ferrari may be looked upon as the one team to have participated in the world championship since its inception, but in fact Enzo was not represented at Silverstone, having withdrawn his cars following a dispute over ‘starting money’. This would happen not infrequently down the years, but on this occasion the absence of the Ferraris — particularly that of Alberto Ascari — was particularly lamented, for it meant that the Alfa Romeo 158s would be unopposed. Juan Manuel Fangio, Giuseppe Farina and Luigi Fagioli were their regular drivers and, in honour of the occasion, a fourth car was entered for Reg Parnell, the leading Brit of the day. All they faced was a selection of elderly Maseratis, Talbots, Altas and ERAs, so it was hardly a surprise that the front row of the grid — four cars at Silverstone until 1969! — was all dark red, with Farina on pole position.

Alfas line up on the grid

Getty Images

A year earlier Bob Gerard had driven his ERA to second place, behind the Maserati of ‘Toulo’ de Graffenried. “I got a lot of satisfaction out of that,” he remembered, “but it rather flattered me — you’ve got to remember that Alfa weren’t competing in ‘49.” So how was it to race against the Alfas? “Oh,” Gerard chuckled, “you didn’t race against them; you just sort of set off for three hours at the same time they did…

“Mind you,” he added, “that was better than the bloody BRM!”

Indeed. Although the V16-engined car was on hand, it was considered as yet unready to race (a state of affairs which was never materially to change), so its first public appearance was confined to three ‘demonstration’ laps. Driven by Raymond Mays, the car went through the corners on the overrun, and did its party piece of making a lot of noise. And the crowds, devoutly hoping that here at last was a British world-beater, cheered ecstatically.

In childhood, I was given an EP record of the V16 making noises, and once mentioned it to Stirling Moss. “I’m surprised,” he said, “that it ran long enough to fill an EP.”

The crowd had hoped to see the much-heralded BRM V-16s. Once again, they were not ready for competition

Getty Images

Even its exhaust note, while undeniably arresting, was no match for the cultured eight-cylinder scream of an Alfa 158, the car at which it was vainly aimed.

“The V16 was a thoroughly nasty car,” said Moss. “The brakes were okay and the acceleration was incredible — until you broke traction — but everything else I hated, particularly the steering and the driving position.” And what of its handling? “I don’t remember it having any.”