The only place Prost felt comfortable that year was when wrapped in Williams’ cocoon. Frank and Patrick were getting it in the neck too. They’d sent their entry in two days late. And rules is rules. This piffling clerical oversight put them at the mercy of the other teams — remind us again why we should let you line up in South Africa, etc. Max rode to their rescue, but then used this ‘saintly’ deed as a stick with which to beat them throughout his anti-gizmo crusade.

More than ever, therefore, the utilitarian factory in the shadow of Didcot’s cooling towers became a citadel. Those on the inside were privileged to witness first-hand a year-long Prost master class; those on the outside, though, could not, or chose not to, see it. Handed demonstrably the best car by Adrian Newey and Patrick Head, and placed alongside an inexperienced team-mate — once-bitten-twice-shy Nigel Mansell had stalked off to Indycars rather than face ‘The Professor’ again Prost found himself in a lose-lose situation. Few appreciated his wiles, his wins, while many gloried in his frustrations, his failures. Professionally, he rose above it; privately, he hated every minute of it.

It was all still intact: the unruffled, unerring speed, the uncanny ability to do just enough – how that could grate sometimes, even with his fans – but would Senna have gone any faster in the same car? Probably. True, Prost had enough in reserve to respond, but would Senna have beaten him to the title even so? Probably.

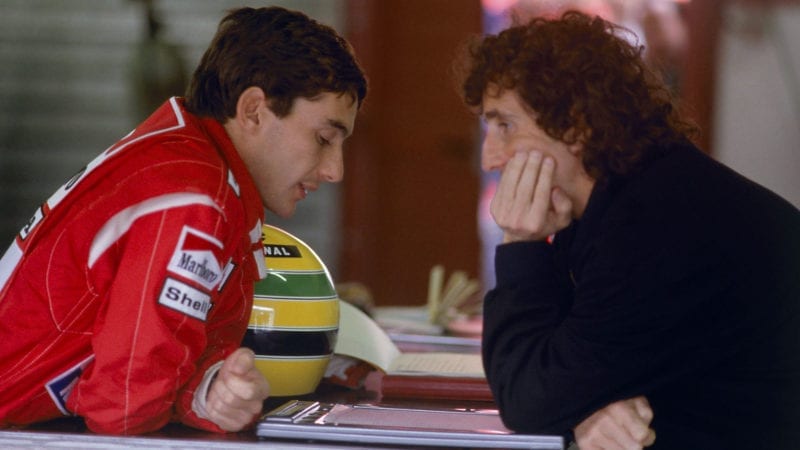

At the height of their McLaren frat spat, the Brazilian had proved always willing to leap onto the next level of risk. On the days when Senna was better, he’d be gone; on the days Prost was better, he knew the Brazilian was never going to let him go, no matter what.

When Prost took Senna off at Suzuka in 1989, he did it hairdresser-style, at 50mph. In fact, he didn’t even take him off. Only he could keep it on the island when ‘crashing’. When Senna took Prost off at Suzuka in 1990, he did it harum-scarum, at 150mph. Only Senna could have taken them so far off.

And that was the difference. Both men had been pushed to the ultimate driving sanction by the depth and intensity of their rivalry, but only one of them had carried it off with any conviction.

Despite his unsubtle, foot-hard-in thwack, the bulk of the sympathy was always going to land at Senna’s door, for he was the racers’ racer, the all-or-nothing qualifier who made his car dance, the quicker man who had been robbed the previous year. Prost, in contrast, was the thinker, the man who won races at the slowest possible speed, they said, the devious one who crossed the talent divide by poring over data and fiddling with springs that went up in iddy-biddy 25lb increments. Who cared if Senna used Prost settings initially? It was minutiae versus maximum attack. No contest.

And so what if Prost scored 12 fastest laps compared to Senna’s six in their two years together – Senna outscored him 26 poles to four.

And it went deeper than statistics. When Prost piped up, he was whingeing; when Senna chimed in, it was a cri de Coeur.

It was easier to like Senna, his heart was on his sleeve. To admire Prost was akin to being in a secret club, required a bit of effort – even though his heart was so obviously in the right place.

Prost fans would carefully construct their case: was it Prost who almost put his team-mate into the pitwall at Estoril in 1988? Was it Prost who manoeuvred Derek Warwick out of a drive? Was it Prost who struck a deal with a driver from another team to compromise his main rival’s race? Valid point piled upon valid point.

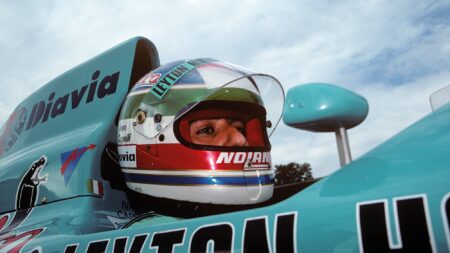

Prost found himself in a winning car for ’93 with Williams

Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images

But all Senna fans had to do to bring this edifice tumbling down was point out that their man was the faster. And Prost fans, being Prost fans, knew this to be true. And it hurt. There was no answer to that speed, that messianic commitment.

Ah yes, but didn’t Prost come so very close to finding the answer? Okay, he basically gave up on qualifying, but is it wrong to shed your weaknesses to concentrate on maximising your strengths? How else are you to deal with such a situation?

Imagine you are Alain Prost, the world’s best driver. Until, suddenly, you are not. Now you’re only the world’s fastest human faced by a God-given talent. There are days when you feel puny, crushed. Yet somehow you win seven times to his eight in 1988. And somehow you beat him to the title in 1989. There are days when you look him straight in the eye and feel the strength rise up within you — and you do for him, in equal equipment. Just like that. And to do this, if your devil is in the detail, then so be it.

And who could blame you for baling out after two years? It must have felt like 10. At least. Nobody else could’ve stuck it.

And how you stuck it to the critics who said you were running scared. How you moulded Ferrari in your own image. It didn’t last, of course. It never could, pre-Brawn, pre-Byrne, but while it did, you were in your pomp. Even Senna was worried, saw you as an equal.

It is for 1990 that Alain Prost should be remembered: the Mexico charge, the bewitching drive at Jerez, the sheer slog of pulling the Scuderia around, the innumerable race distances in front of empty, soulless grandstands.

He seemed stronger, yet strangely more vulnerable, than he had ever been. He didn’t call impromptu press conferences to bemoan his fate, or make grand sweeping gestures, he simply knuckled down and punched over and above his weight.

But why, oh why, did he let that chink of light shimmer down the inside at Suzuka’s first corner? He’d nailed the start, another Jerez appeared on the cards. But then he eased left, cracked open the door — and Senna put his boot against it.