'66 Le Mans aftermath: Ford cars win - but which one?

Timing issues leave the result of 1966 Le Mans in confusion

Motorsport Images

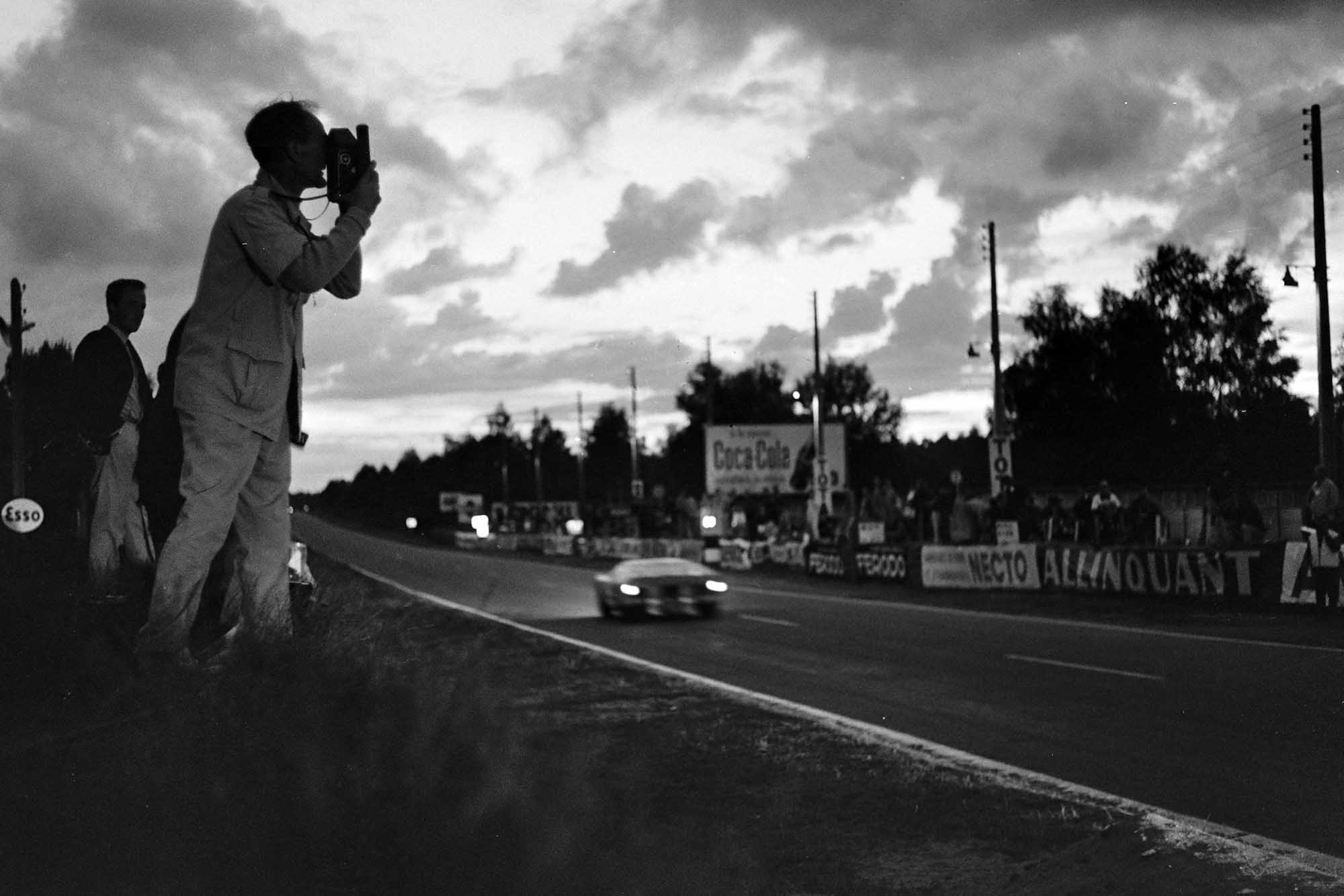

The 24-hour race at Le Mans is now six weeks old and the vast American armada that came over and slaughtered “poor little Ferrari,” to use Enzo’s own words, has long since returned to the United States, but for numerous reasons I feel justified in referring back to that event and to the report that appeared in the July Motor Sport. With the race being held at the time that our printers normally have the magazine on the printing presses, everything was done in a rush, and older readers had to get out their magnifying glasses to read the tiny print.

Even so, the report was skimped and there was no room to express opinions or enlarge on any of the interesting points that arose during the 24 hours’ racing, while the inevitable inaccuracies crept in, that might have been avoided a day or two afterwards. When you have been up all night the brain is not all that clear and by 7 p.m. on Sunday evening, when the weather had turned wet and dismal, it was easy to overlook things, especially when the “office runner” was fidgeting to snatch one’s writings and speed off to catch an aeroplane.

The big thing that was overlooked by a great many onlookers was that it made no difference what the Fords of McLaren/Amon and Miles/Hulme were doing as they got the chequered flag, for the race had finished at 4 p.m. exactly, not when they arrived at the finishing line. Timekeepers can only work on car numbers and time readings as recorded at each crossing of the timing line, so with a race that is measured on time and not distance they cannot hope to know exactly where all the competitors are as the official clock reaches 4 p.m.

In such a long race it is unusual for the first and second car to be on the same lap so there is seldom any discussion about who is the winner, but it is open to calculation or estimation as to exactly where each car is at precisely 4 p.m. on Sunday afternoon. Unless a car arrives at the timing line exactly at 4 p.m. it must have covered a certain number of whole laps plus a portion of a lap, and most drivers try to judge their last lap to make the portion as near as possible to a complete lap. The timekeepers calculate the position of each car on the last lap by taking the time for the penultimate lap and assuming that the car keeps up the same average speed for the last lap.

If a car arrives at the finishing line one minute after 4 p.m. then it is credited with its total number of laps recorded at 4 p.m., plus the portion of a lap it would have covered during the time of its penultimate lap less one minute, at an average speed the same as its penultimate lap. All this is written in the regulations and the numerous loop-holes or errors in the system are covered by various rules, and generally speaking it gives a fair result.

Ken Miles: the real winner in ’66?

Motorsport Images

In the case of the two Fords their penultimate lap was done in close company so their lap times must have been identical. As they were on the same total number of laps the timekeepers could only credit them with the same extra portion of a lap, so that as far as the timing clocks were concerned at 4 p.m. the two Fords were somewhere between Arnage corner and the finish and since 4 p.m. on Saturday they had covered exactly the same distance, except that they had not started side-by-side, Miles had been 20 metres ahead of McLaren on the line-up at the start, so therefore McLaren had covered that 20 metres more than Miles as 4 p.m. on Sunday was reached.

What happened at 1 sec. or even 1 min. after 4 p.m. on Sunday was of no interest to the timekeepers, for the race had finished. In actual fact the McLaren car crossed the finishing line something like a length in front of the Miles car, but Ken Miles was making it very obvious that he was holding back on orders. One of our keener readers was above the pits of the Shelby team, which is closest to the finishing line, and wrote very strongly to point this out, but, as I have said earlier, the race was officially already over, and McLaren was the winner whether he wanted to be or not. In the Shelby pits the team knew about the rules regarding “portions of the last lap before 4 p.m.” and about the dead-heat rule, so there should not have been any confusion, but when you have been awake from 8 a.m. on Saturday morning it is not surprising that one’s thoughts are not too clear by 4 p.m. on Sunday.

In order to fox the timekeepers and the rules completely you would have to arrange for your two cars to do their penultimate laps at different average speeds, so that the difference in m.p.h. when translated into distance would nullify the distance they were apart on the starting line, and if you could do that you would deserve a dead-heat, although I am sure the Timekeepers’ Federation would still produce a trump card from somewhere. It might be worth sparing a thought for the timekeepers next year at Le Mans.

The actual time recording is done automatically by each car being fitted with a battery-operated “bleeper” that sends out signals all the time. As the car passes the timekeepers’ building it records its passage and the signals are fed into a vast electrical machine that ticks away absorbing all this information, and eventually spews out a sheet of paper with the complete race situation, on time and laps. This electronic masterpiece is by I.B.M. but, like so many things electrical, it can suffer mental blocks and, of course, it lacks vision. The result is that a car can be recorded and annotated as having done a certain number of laps in a given time, which would put it in tenth place for example, even though it blew up or crashed minutes before, Until the eleventh place car does more laps for the given time, then the tenth car stays in the race, even though the unfortunate driver may be in hospital.

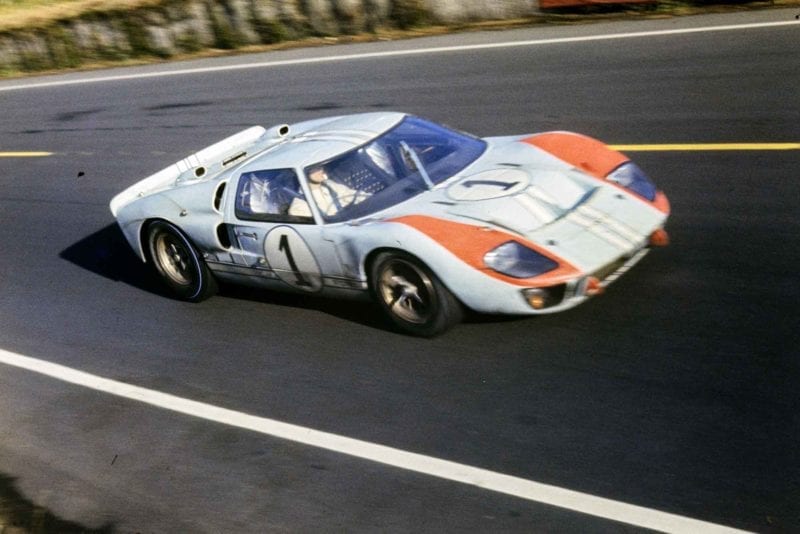

Confusion reigns as the two Ford GT40s reach the finishing line

Motorsport Images

On paper a car can often be proved to be in third or even second place; when you know perfectly well it has been in the dead-car park for 15 minutes with a broken crankshaft! In the small hours of the morning this can be most confusing if you are watching the race itself. A year or two ago the I.B.M. machine got the hiccoughs or something and produced printed results at 5 p.m., 6 p.m., 7 p.m. and so on that bore no resemblance to what was happening out on the circuit, and you did not need a lap chart one hour after the start to realise that the electronics had gone wrong.

This year the I.B.M. machine got an attack of the collywobbles for it produced a sheet that was headed “Race position at 1 hour 15” and the time for the leading car was 1 hr. 13 min. 23.4 sec.! It then went really to pieces and printed excellent results sheets at 2 hr., 3 hr. and so on, except that someone must have jogged its elbow just as the printing started, for 95% of the letters and figures were illegible, and people who wanted to know the instant situation of the race were going berserk for they had a splendid official piece of paper that was unreadable. I am happy to say that after a short period of nothing at all, which was more satisfactory than something you could not read, the electronics functioned normally and all was well. You may think that drivers in the Le Mans race have a lot of drama, but they are not alone, believe me.

To revert to another subject, when gathering incident information it is not always possible to talk directly to the people concerned, and it’s a lucky fellow who can be everywhere at once. so that you have to sift all the information and try to piece together a story. On the matter of the accident at the Esses which eliminated the works P3 Ferrari driven by Scarfiotti, it seems I was completely wrong, as were most other versions of the story. Another of our keen readers was spectating at the spot and kindly wrote a long letter putting things right, and I quote his words : “It was the Matra–B.R.M. which was the first to spin (Schlesser), and the C.D., being very close behind, shunted it. The cars finished up on the outside of the track with the C.D. being shielded from oncoming cars by the Matra-B.R.M. which was facing the right way after all the spinning. The next car through the Esses was the works Ferrari (Scarfiotti), a full ten seconds behind the first two cars, but as the crash had taken place going out of the Esses, following drivers were “blind” to the accident [The course at this point runs between high banks.—D. S. J]

Poor Scarfiotti came through the corner with his car under complete control, only to be confronted with the rear end of the Matra-B.R.M. [Do not write in about flag-marshals, as it was in the dark, and the yellow danger lights cannot be at every point where there is an accident.—D. S. J.] The slippery conditions of the track were forcing all drivers to use the full width of the track … and Scarfiotti had no chance at all .. . the Matra-B.R.M. was first in the firing line.” Mr. Whitfield, who was the reader concerned, goes on to criticise the way certain drivers approached the hazard, now that the “accident lights” were flashing all the way back to the pits, and to compliment others for skilfully preventing an even greater pile-up of cars.

I am always extremely grateful for such helpful letters, for obviously I cannot be everywhere at once on a big circuit during a long race, and at the time there were many criticisms of Scarfiotti, so it is nice to have confirmation that he was not to blame. My only regret is that it is not possible to gather together all such observant readers after a race and to produce a race report second to none. Two readers wrote to point out that the caption on page 632 bore no relation to the photograph! As the photographic staff left Le Mans I requested that there should be a photo of the Miles/Hulme car on the centre-spread as I felt they were the moral winners. The caption was reasonable enough, but the photo was of car number 7, not car number 1, which was the Graham Hill/Brian Muir Ford Mk. II. Apart from seeing the 7 on the driver’s door [It looks like a 1 on the scuttle—Photo. Dept.], this reader points out that the Miles/Hulme car did not have external mirrors, a bug-deflector, or tape over the headlights!

I feel we now have a slightly better idea about certain aspects of the 1966 Le Mans, but by no means complete, for with 55 cars and 110 drivers taking part, two sets of pits in operation, the working ones at the tribunes and the signalling pits at Muisanne, literally thousands of photographers, journalists. Television, Cinema and Radio people, to say nothing of the vast army or officials and organisers, a whole book could be written on the happenings between 4 p.m. Saturday and 4 p.m. Sunday, and it would take a very large number of writers to gather the information. Perhaps it is the enormous scale, the chaos and confusion of Le Mans that is the real fascination of the event.