1966 French Grand Prix race report: Aussie rules

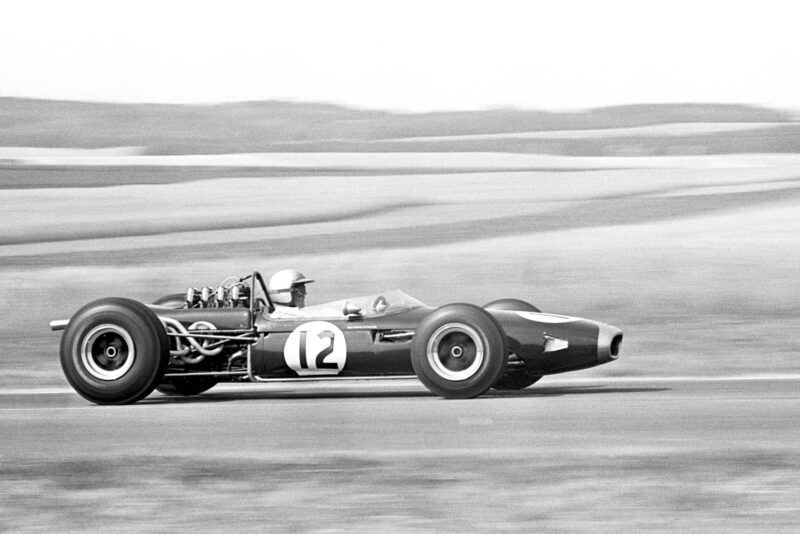

Jack Brabham claims a famous first win for his eponymous team; Ferrari's Mike Parkes takes impressive second place on grand prix debut

Jack Brabham celebrates his first win of the season

Motorsport Images

Since the previous Grande Epreuve there were two questions outstanding, what would John Surtees drive as he had terminated his contract with the Ferrari team and whether the H16 BRM would he sufficiently developed to run well in practice and also to race? The first point was solved when the Cooper team arrived at Reims with three Cooper-Maserati V12 cars, and the second point was settled during the final practice session. The Cooper-Maseratis were the two that Rindt and Ginther had been racing and a brand new one making its first appearance.

Chris Amon had already been taken on by Cooper to replace Ginther, who had returned to Japan and the Honda team, so when Surtees joined Cooper it was decided to run a full team of three cars. Rindt drove the car he has had all season, Surtees took over Ginther’s car and Amon had the brand new one. With the moving about of drivers Ferrari gave Mike Parkes the second place in the Ferrari team, with Bandini, and they both had 12-cylinder 3-litre cars, the Italian driving the one previously used by Surtees and Parkes having a new one with more length in the cockpit and forward portion, in order to accommodate his long legs.

Team Lotus were still in the same unhappy situation as at Spa, with Clark driving the 1965 chassis R11, with the 2-litre Coventry-Climax engine, and Arundell with the Lotus 43 with BRM H16 engine, still in a rather “prototype” condition. The works BRM team were in a worse state, for Stewart was still unfit to race, following his Spa accident, and his car was still being repaired, so Graham Hill was all alone with the remaining 2-litre V8 car and two unraced H16-cylinder cars, and he had to concentrate on trying to get the new cars race-worthy rather than trying to win, for the 2-litre could not hope to be fast enough on the Reims circuit.

The Brabham team were in a much better situation for not only did they have Brabham’s own Repco V8-engined car and the reliable 2.5-litre Coventry-Climax-engined car, but also a brand new chassis and V8 Repco engine, which Hulme was to drive for the first time. The rest of the entry was made up by private owners. Gurney with his Eagle-Climax. Spence with Parnell’s 2-litre Lotus-BRM V8, Anderson with his Brabham-Climax, Siffert with the Walker/Durlacher Cooper-Maserati, Ligier with his own Cooper-Maserati, John Taylor with the David Bridges 2-litre Brabham-BRM V8, and to complete the list Bonnier with a borrowed Cooper-ATS V8 as his Cooper-Maserati had not been repaired since his Spa accident.

Qualifying

After Surtees departure from the team, Mike Parkes was drafted in as replacement

Motorsport Images

The Reims race is run by the Automobile Club de Champagne, and they have more than sufficient influence over local conditions, so that in spite of the fast downhill leg of the circuit from the Muizon hairpin to the Thillois hairpin being on the main Soissons-Reims road there is no trouble about closing the roads and having sufficient time for practice. There were three sessions arranged, each one being in the early evening, and they were on Wednesday, Thursday and Friday of the week previous to race day. For Saturday a Formula Two race was arranged and the French Grand Prix was to be on Sunday, July 3rd.

During the first practice Surtees set the pace with a Cooper-Maserati and it was not long before it was very obvious that the 3-litre cars were really at home on the super-fast Reims circuit, the various interim 2-litre “specials” not being in the picture. The lap record from 1960 still existed, which Brabham set with a 2½-litre Cooper-Climax at 2min 17.5sec, while the unofficial fastest ever was 2min 16.8sec, which the same driver/car combination recorded during practice that year.

Graham Hill and Clark both improved on these figures with their 2-litre V8 cars, which was reasonable enough, hearing in mind how old-fashioned the 1960 works Cooper was, by present-day standards, hut Surtees and Rindt with the 3-litre Cooper-Maseratis really put things into their right perspective when they got well under 2min 12sec.

Graham Hill was getting one of the 16-cylinder BRM cars round in about 2min 15sec, but was not doing any consistent laps with either car, and Team Lotus had their BRM engine shear its distributor drive before it left the paddock, so Arundell did not do any practice.

As the latest 3-litre Brabham was not ready Hulme had one flying lap in Brabham’s car to get the feel of things, and Brabham himself was going very well and holding Rindt’s Cooper-Maserati on speed. The Ferrari team did not arrive for this first practice, so Surtees and Cooper-Maserati were unchallenged, his ultimate time being 2min 10.7sec, just over six seconds better than ever seen before at Reims.

On Thursday evening the two 12-cylinder Ferraris arrived at the circuit and Hulme’s new Brabham-Repco V8 was ready. Bonnier turned up with the “special” built by Alf Francis comprising the front half of an ex-works Cooper space-frame chassis, with his own rear end grafted on, powered by a 3-litre version of the sports ATS V8 engine and driving through a Colotti gearbox. The BRM H16 engine in Arundell’s Lotus had been repaired, but he set off from the pits in the wrong gear and burnt the clutch out as he went out of sight, so the car did not run for long.

Graham Hill was concentrating on the second of the works 16-cylinder cars but was not too happy with the gear-change, even though the cable-operation had been changed to rod-operation since Spa. In the Lotus pit there was more gloom than ever for Clark ran into a bird at high speed and the resultant damage it did to his left eye put him out of action for the rest of the meeting.

There was a feeling that the time set by Surtees on the previous evening was not going to be beaten easily, and some people were thinking that Bandini, in his new role of Ferrari team leader, was not going to look very impressive. However, he soon wiped the smiles off the faces of the Surtees fans for after a few laps to settle in he approached the Cooper-Maserati time of 2min 10.7sec very quickly, and then went way below it with a series of three quick laps in succession. His times were 2min 10.1sec, 2min 09.8sec and a 2min 09.2sec, and he didn’t look as though he had been trying very hard.

“There was a feeling that the time set by Surtees on the previous evening was not going to be beaten easily”

Parkes was getting on very well in his first go in the 3-litre Ferrari and Brabham was busy “breaking in” Hulme’s new 3-litre Repco V8. This second Grand Prix Brabham chassis had a space-frame of round tubes as against the first car’s combination of oval and round tubing; other than this it was to the same specification. Amon was gradually settling in with the Cooper team, his first practice having been fraught with braking troubles and sticking throttles, but things were now improving.

It was very clear that no one was going to match Bandini’s Ferrari for sheer speed and that a “tow” in the slip-stream was going to be very worthwhile. Surtees and Rindt got together and set off with the sole intention of aiding each other by slip-streaming and “leap-frogging,” with the object of getting Surtees’ car into the Ferrari’s slip-stream and thus recording one quick lap before Bandini noticed what they were doing. The two Cooper-Maserati drivers waited their opportunity and then while the two Ferraris were going mound they pounced on them. It worked perfectly and before Bandini realised what was happening he had provided a very high-speed “wind-break” for Surtees and the Cooper-Maserati recorded a lap in 2min 08. sec. A true time but achieved artificially.

Surtees qualified 2nd for his new Cooper team

Motorsport Images

They had all gone past the pits in a great rush and going very fast indeed, and everyone waited with interest to see the next lap. Bandini and Parkes were not going to be “used” again and the four cars came slowly past the pits, each waiting for someone else to lead! They then called a truce and the Cooper-Maserati drivers came in, Rindt being really happy at having been able to work so neatly with Surtees. As practice finished Parkes did a lap unaided or unhindered in 2min 11.9sec, which showed that he was getting the hang of high-speed single-seater driving. Thanks to a bit of good team work, Surtees still held pole position but he realised it was artificial and could not last, for unaided a Cooper-Maserati did not seem likely to break 2min 10sec.

On the final evening of practice there was plenty of activity, With Graham Hill trying Firestone tyres on the newest 16-cylinder BRM, Arundell was still in trouble with the Lotus 43, the 16-cylinder engine breaking its distributor drive again, but in a different place this time, and the V8 Lotus-Climax was awaiting a driver as Clark was out of the running. Both V8 Brabhams were going well and Hulme also did some laps in the 4-cylinder Climax-powered car, preparatory to “hiring” it to Bonnier, as the Cooper-ATS had not proved very successful.

With the Lotus 43 out of action Arundell put in some laps with Clark’s V8 car and meanwhile Chapman was negotiating tor Pedro Rodriguez to take over Clark’s entry. Unable to get a high enough axle ratio R11 was using 7.20 x 15in rear tyres, which made it look distinctly odd. Arrangements were suitably conducted with the organisers and Rodriguez took over Clark’s entry and started practising with the car.

Graham Hill had been doing a lot of starting and stopping and single laps with the newest H16 BRM, which he preferred to the original car, and was steadily getting everything working in unison. Each time past the pits it had not been making much of an impression, for although it was going quite fast it was not outstanding. Suddenly it appeared out of Thillois hairpin on its own and everyone was conscious that the 16-cylinder engine was really “growling”. There was no doubt that it was working on all 16 cylinders and turning at well over 10,000rpm and many hands reached for stop-watches as it hurtled past the pits faster than anything yet seen.

Next time round it was travelling just as fast and Hill kept it going to record two flying laps at 2min 09.4sec and 2min 09.2sec. He was doing this holding the gear-lever in gear with one hand, as there was a tendency for it to jump out, and also having to make gearchanges that were desperately slow. In spite of all this he made these creditable times, obviously on sheer speed down the Thillois straight (188mph was estimated), and on acceleration. This was the first time anyone had seen the new BRM really on “full song” and it was a very impressive sight, and the fact that it had broken 2min 10sec unaided, which so far only the works Ferrari had done, spurred Bandini into action.

He went straight out and did 2min 08.8sec and followed it up with 2min 08.5sec, so it was clear that he could improve on the “artificial” time that Surtees had made, whenever he felt like it. Bonnier was not doing justice to the works Brabham, which was upsetting a lot of people who knew what a good car it was, and Parkes was supporting his team-mate well and got down to 2min 09.1sec to snatch third time overall from Graham Hill.

With barely five minutes of practice left there was a series of fast laps put in by Surtees, Brabham, Parkes and Banditti and at one point they all went by in a solid bunch and very close together so that even the most hardened race-goers in the pit area stepped back a few paces and we saw a brief glimpse of what Grand Prix racing is going to be like in a year or two when everyone has got their new cars fully developed. As the end of practice approached Bandini got clear of everyone and took his Ferrari round on its final lap in a shattering 2min 07.8sec, at an average speed of 233.852kph (approx 145mph) thus putting the Cooper-Maserati team in their place and leaving all the 2-litre “interim” cars very breathless.

Race

The flag falls as the cars get underway

Sunday proved to be extremely hot and before the start the cars were being soaked with damp covers, fuel pumps were being soaked in water, fuel tanks were covered up and everyone was trying to prevent the blazing sun from making the tot conditions unbearable for drivers and the machinery.

Rodriguez was to drive Clark’s V8 Lotus-Climax, the H16 BRM-engined car had been repaired once more for Arundell; the Cooper team seemed confident, with Rindt and Surtees having the latest Maserati engines which use coil valve springs instead of the original hairpin valve springs, while all three were on Dunlop CR70 tyres and Rindt’s car had high cockpit sides added. The engines in the cars of Amon and Surtees were fitted with forward-facing ducts on each row of air intakes, while Rindt had the standard gauze covets.

The Brabham team had their two V8 engine cars ready and Graham Hill was to drive the 2-litre V8 BRM as the gearbox problems on the H16 car could not be overcome. The two works Ferraris were on Firestone tyres, with bolt-on front wheels and centre-lock rear ones, and Gurney’s Eagle, like the works Brabhams was on Goodyear tyres. There were seventeen starters altogether and they went off on a warm-up lap before lining up on the “dummy-grid” for the 48-lap race.

Surtees was in the middle of the front row, which gave great encouragement to the Cooper-Maserati team, but there was a works Ferrari on each side of him. In the second row were Brabham and Rindt, so that 3-litre Grand Prix cars dominated the scene, showing that the new Formula is gathering momentum in a satisfactory way. As Raymond Roche, the “big boss” of Reims, waved the French flag and ran for the side of the track Surtees leapt into a slight lead, with the two Ferraris alongside and Brabham hard on their tails. Before the end of the pit area Surtees was in trouble and his car slowed, Brabham diving to the right into Bandini’s slipstream as they all went under the Dunlop bridge.

Bandini got away well, but Brabham was hanging onto the very end of the Ferrari’s slip-stream as they finished the first lap, and they were followed by Parkes, Amon, Rindt, Siffert, Hill, Hulme and the rest, with Surtees obviously in trouble in thirteenth position. Arundell drew into the pits with the 16-cylinder Lotus-BRM with gear-change difficulties and on the next lap Surtees drew into the pits, the Cooper-Maserati not running at all well. Already Bandini had set a new lap record, on his first flying lap, with a time of 2min 13.6sec, but Brabham was driving as hard as he knew how and was hanging on to the Ferrari, the rest of the runners already well behind.

The Cooper-Maserati people thought that the trouble with Surtees’ car was over-heating in the fuel system and vapour locks forming, and they revved the engine and undid pipes and tried to evict air bubbles, and during this the engine got very hot and blew the water system overflow pipe out, which whirled round like a snake, pouring out steam. Then they discovered that a small shaft driving the mechanical fuel pump had sheared and the engine had been running on the electric pressure-pump only, which was not enough for the injection system, and they set to work to replace the drive, which meant that all hopes of Surtees challenging the Ferraris had gone.

Arundell did two more laps with the Lotus 43 and then gave up the unequal struggle with a gearbox that would not stay in gear, and after only five laps Siffert’s fuel system began to suffer from the heat and vapour locks were forming in the pipes, the Cooper tanks being rather vulnerable to engine and exhaust pipe heat which was aggravated by the very high air temperature.

Meanwhile the leading Ferrari was running splendidly and Bandini was steadily making new lap records, his times descending into the 2min 12sec barrier and then on down into the low 2min 11sec group. Slowly but surely he was pulling away from Brabham and at twelve laps, which was quarter-distance, he had a two-second lead, which does not sound much, but, at the Reims average speed, is a long way.

Behind these two there was a four-some comprising Hill (BRM), Parkes (Ferrari), Amon (Cooper-Maserati) and Rindt (Cooper-Maserati), and they were passing and re-passing, the slower cars using the Ferrari to “tow” them along. Considering it was his first Grand Prix race Parkes was doing remarkably well, and though Graham Hill was almost touching the Ferrari tail pipes at times and would pull out alongside and take the lead as they went into the fast right-hand bend past the pits, Parkes held his end up.

“Graham Hill was almost touching the Ferrari tail pipes at times and would pull out alongside and take the lead as they went into the fast right-hand bend past the pits, Parkes held his end up”

This battle did not last very long for Amon felt his car handling in a peculiar fashion and stopped at the pits to find his left-rear hub nut had come loose. He was quickly back in the race after it had been tightened but he had lost all contact with the other fast runners. Rindt’s car began to lose power, due to the effects of the heat somewhere along the fuel lines and he was caught and passed by Hulme in the new Brabham-Repco V8, and then on lap 13 the 2-litre V8 BRM gave up the struggle against the 3-litre Ferrari and Hill drew into the pits with a broken inlet camshaft, the engine running in a very rough fashion on four cylinders.

All the excitement was now over, Bandini was comfortably in the lead, Brabham was firmly in second place, Parkes was third having had his adversaries fall by the wayside, Hulme was a steady fourth, with Rindt a little way behind and a long way back was Rodriguez, still on the same lap as the leader, but Amon whose engine was now having vapour lock problems was about to be lapped.

At the back of the field there was the rather pathetic sight of Dan Gurney running side by side with Bonnier, the Eagle being rather crestfallen with its low-powered 4-cylinder Climax engine, but until the Weslake 12-cylinder 48-valve engine is ready poor Gurney is going to have to suffer such indignities.

Surtees now set off from the pits with a new pump drive fitted, not with any hope of racing, but just to see if the opening lap troubles had been cured. After two laps he coasted to rest at Thillois (see centre-spread photographs) for the overheating of the engine at the pits had done some internal damage. Relentlessly Bandini and Brabham were lapping the other competitors and the Ferrari lead was up to eighteen seconds, but even so Brabham was not relaxing, though he was comfortably ahead of Parkes in the second works Ferrari, while Hulme was fourth going fast enough not to be in danger of being lapped by the leader.

“As Bandini came down the hill to Thillois on lap 32 the throttle cable of his Ferrari broke by the pedal and with shut throttles he came to rest at the hairpin”

All the Cooper-Maseratis had been affected by the heat, both works team and private-owner cars, though Rindt, Amon and Ligier were still running. Anderson was having a very good non-stop run in his Brabham-Climax and was gaining positions as faster cars fell out, as was Rodriguez With Clark’s Lotus, while Taylor was bringing up the rear steadily and consistently, ahead of Amon, Ligier and Bonnier who had all spent time at the pits.

On lap 30 Bandini set a new lap record in 2min 11.3sec, obviously well within his limits and running splendidly, but as he came down the hill to Thillois on lap 32 the throttle cable of his Ferrari broke by the pedal and with shut throttles he came to rest at the hairpin. While he tore a length of wire from a straw bale and tied it onto the linkage at the back of the engine, Brabham sailed by into the lead, to the cheers of the anti-Italian element. Operating the throttles by means of the length of wire held in his hand (see photo on centre-spread) Bandini got back to the pits, but he had already lost a lap to Brabham.

The repair was not simple, for it meant fitting a complete new cable and all hopes of victory for Bandini were now gone, and Brabham was forty seconds ahead of Parkes, with no fear of being caught; Hulme was securely in third place so that the Brabham team were very happy indeed. Other people’s troubles had allowed Rodriguez to move up to fourth place, but with only eight laps to go he drew into the pits with his Climax engine making a horrid jangling noise. A high-pressure oil pipe had broken and he had driven round to the pits without any oil pressure.

This now let Anderson into fourth place, a long way behind the leader, but still running regularly. As the leader was on his forty-second lap Bandini rejoined the race, but he could not hope even to qualify, and the order was Brabham, Parkes, Hulme, all on the same lap, with the remainder of the runners two or more laps behind.

With Bandini out of the running, Brabham was unassailable

With two laps to go Hulme suddenly came to rest out on the circuit, his fuel pump failing to deliver the last few gallons of petrol from the tanks, but he lifted up the front end of the car and managed to get enough through to complete the lap, with his fingers crossed, and meanwhile Brabham completed his forty-eighth lap and ended the race.

Hulme was not alone in a last-minute drama, for Anderson’s final drive in his Hewland gearbox had broken and he just managed to get to the finishing line, but lost his fourth place, being passed by Rindt, Gurney and Taylor as he limped up the final straight and waited for the race to finish. As the race had drawn to a close and the air temperature dropped rapidly with the approach of thunderstorms the Cooper-Maseratis of Rindt, Amon and Ligier had recovered and got rid of their vapour lock problems, but it was all too late.

Reims Ramblings

- It would seem to be a good year for Goodyear tyres, for after equipping the winning car at Le Mans, they equipped the winning Brabham for this Grand Prix victory, to add to their numerous wins in Formula Two with the Brabham team.

- During practice there was a lot of discussion and speculation about Surtees leaving a Shell petrol supported team and driving for a BP supported team. All the bickering was nullified for Brabham won on Esso!

- With numerous practice laps at well over 140mph averages the Reims circuit lived up to its reputation for high-speed and flat-out motoring, and without Hollywood cluttering up the place everything was pure reality, including the bottles of champagne given for the fastest practice laps.

Even the rival teams were delighted with 40-year-old Brabham’s victory, while Mike Parkes’ second place in his first Grand Prix race was greatly admired.