1961 French Grand Prix race report: Baghetti's immaculate debut

In his first ever race, Giancarlo Baghetti snatches the win right at death from Dan Gurney in thrilling race

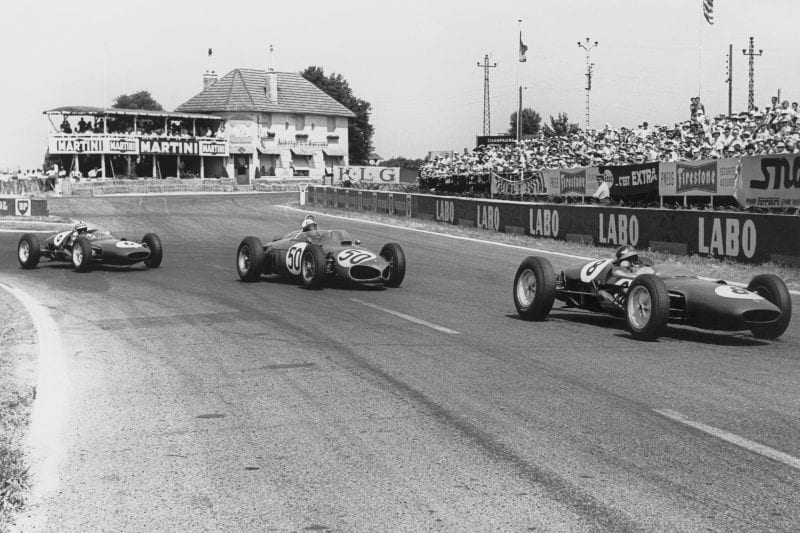

The start of the 1961 French Grand Prix at Reims.

Motorsport Images

After the Spa race, where Ferrari cars dominated, everybody was resigned to an even greater demonstration of mechanical superiority on the fast Reims circuit. In the Belgian GP the rear-engined Ferrari cars had had no trouble at all in finishing 1-2-3-4 and one felt that if the Scuderia cared to bring along six cars to Reims they would finish 1-2-3-4-5-6 without difficulty.

As it was, the SEFAC entered only three works cars, for Phil Hill, Ginther and von Trips, nominated in that order, but a last-minute entry with a Ferrari came from FISA, the group of Italian racing clubs to whom Ferrari has loaned a rear-engined V60-degree car for this season, and needless to say their driver was Giancarlo Baghetti, the phlegmatic-looking, plump Italian, risen from the ranks of last year’s Italian Formula Junior. Naturally both car and driver were being looked after by the Scuderia, so in effect there were four works Ferraris once again.

The Automobile Club of the Champagne had no truck with seeding or qualifying and virtually said “Let them all come,” so that practically everyone in Formula 1 racing was present for this World Championship event. The Cooper factory had Brabham and McLaren with their regular 4-cylinder Climax-engined cars, though there were a lot of crossed fingers beforehand in the hope that at least one V8 Climax engine would be ready, and that Brabham would have it in his car, but hopes were in vain.

French Grand Prix at Reims.

Jim Clark at the wheel of a Lotus 21.

Motorsport Images

Colin Chapman had the two brand new 1961 Lotus-Climax cars that appeared at Spa, again being driven by Ireland and Clark, and they had the earlier 1961 car as a spare. Clark’s car was on SU carburetters again, the others being on the almost universal Weber carburetters that have won Grand Prix races almost unchallenged. The Porsche factory seem to be in as much trouble with new projects as do Coventry-Climax, their exciting flat 8-cylinder engine is said to be giving only 160bhp and not too reliably at that, while the new chassis with the coil spring and wishbone front suspension seems to have disappeared altogether, along with the fuel-injection.

They had their three old cars from last year, all on Weber carburetters, two for Bonnier and Gurney and the third should have been for Herrmann but was changed to de Beaufort. The BRM team had completely overhauled three cars, all with Climax engines, stripping everything to pieces after Spa and rebuilding the lot so that Graham Hill and Brooks had the best machinery that Bourne could produce, until such time as their V8 is ready; it being in the building stage at present. These two drivers also had a spare car for training.

Stirling Moss was driving the Rob Walker Lotus Special, as used at Spa, with the last year’s chassis frame, fitted with this year’s rear suspension, a Colotti 5-speed gearbox and the new sleek bodywork. Their spare Lotus from last year sits at home hopefully awaiting the V8 Climax engine, for which it has been modified in readiness. UDT-Laystall brought along three cars, all standard Lotus-Climax, two with their own new bodywork which is sleeker than the production Lotus, for Henry Taylor and Lucien Bianchi, the Belgian driver being taken on in the team to replace Allison who was injured at Spa.

The third car was a spare and was a standard production type Lotus-Climax of 1960 type and all three cars were using Lotus sliding-spline gearboxes, the Laystall built gearboxes having been abandoned for the time being. The Scuderia Serenissima entered two cars, the old Cooper-Maserati with the new square-cut bodywork, which Trintignant was down to drive, and a brand new car built by Alessandro de Tomaso in conjunction with OSCA. This was a nicely turned out chassis on Cooper lines, with wishbones and coil springs all round, and in the rear was a 4-cylinder OSCA engine and five-speed gearbox of very compact and neat layout. As the OSCA engine was not giving as much power as a Climax engine, 140-145bhp being its top limit, the car was a bit outclassed. It was entered for Scarlatti to drive.

Willy Mairesse in #48 Lotus 21-Climax and Henry Taylor in #30 Lotus 18/21-Climax.

Motorsport Images

Casner’s Camoradi International set-up had their new Cooper and old Lotus cars entered for Gregory and Burgess, respectively, and the Yeoman Credit Racing Team run by Parnell brought along three Coopers for Surtees and Salvadori. They had two normal 1961 production Coopers and their own narrowed-down modified Cooper with 5-speed Colotti gearbox, all three cars having Climax engines of course, though one of the standard cars was using SU carburetters.

Another 1965 Cooper-Climax was the privately-entered one of Jack Lewis, nicely turned-out and straight from his very good race at Spa, while the Frenchman Collomb also had a 1961 Cooper-Climax. There were two more entries for the Equipe National Belge, to be driven by Gendebien and Mairesse but as they could see little future in the Emeryson-Maserati cars on such a fast circuit they withdrew and Seidel arrived with his two old Lotus-Climax hoping to get himself and the Swiss driver Michael May in the field. There being no fourth Ferrari for Gendebien the Le Mans winner did not bother to turn up and Mairesse came along with a beady eye on the spare works Lotus, so the Seidel team got only one entry which went to May.

“Here was no shadow of doubt that the small rear-engined Ferraris were quite uncatchable on a fast circuit”

Practice for the 47th French Grand Prix began on Wednesday evening, and the Champagne Country was showing signs of living up to its tradition of being very hot, even as late as 6pm when practice began, following a Formula Junior practice. In the pits there was an awful feeling of hopelessness amongst the Coventry-Climax-engined brigade, even though every self-respecting car was using the new Mark II engine, these being in plentiful production. When the three red V120-degree Ferraris and the red V60-degree car came out of the paddock, making a lovely sound which echoed between the concrete pits and the cantilever concrete roofs of the grandstands opposite, everyone felt “the massacre is going to be worse than at Spa.”

For many years there has been universal disbelief of the bhp figures claimed by Ferrari for his engines, but occasionally he has proved conclusively that they were not far out, as at AVUS in 1959, but now the tune was different, it mattered not whether his bhp quotes were disbelieved, there was no shadow of doubt that the small rear-engined Ferraris were quite uncatchable on a fast circuit, and Reims is one of the fastest. Brabham and McLaren went out to circulate in close company as did Phil Hill and von Trips, and while the Ferraris were happy the Coopers were soon back, to disappear behind the pits and change their axle ratios.

Qualifying

Carlo Chiti, Ferrari engine designer sitting on the pit wall with Phil Hill and Richie Ginther.

Motorsport Images

There were no cars from Porsche out for this first practice, nor from Serenissima or Seidel, but BRM, Yeoman Credit, Lotus and UDT were all using their training cars, and as they all had the same sort of “T” on the side any times recorded by them were not attributed to any given driver, the timekeepers only recognising numbers and tying these up with drivers from the list in the programme. In consequence people like Surtees who did a quick lap in the training car were not given credit, and Taylor who did his best lap in Bianchi’s car was not credited. Bianchi was actually still on his way back from the Alpine Rally, but he was credited with a lap time!

The works Ferrari team were soon cruising round feeling out the lie of the land, and Baghetti was going slowly round finding the way, this being his first visit to Reims. The British cars, led by Brabham, were lapping in just over 2min 30sec, the Cooper works drivers best being 2min 31sec, but Ginther began to show the Italian team’s paces when he put in 2min 28sec.

Moss was not at all happy with the handling of his Lotus “bitza,” though it was difficult to put a finger on anything very definite being wrong, and he was approaching the 2min 31sec mark. He briefly tried one of the UDT-Laystall cars but did not seem to prove anything, and was soon back in his own. Then he had a lucky break, for he managed to get tucked well in behind von Trips who was lapping at around 2min 30sec and the German driver underestimated the Moss cunning and craft, and overestimated the potential of his Ferrari.

He started to really open out down the straights thinking to leave the Lotus way behind, but Moss was so well tucked in that he was sucked along in the slipstream and, of course, von Trips had no hope of shaking him off on the bends or on braking. The result was that they went faster and faster as von Trips became more amazed at seeing Moss still behind him and he never gave a thought to the fact that he was unwittingly providing Moss with a good lap time. It was not until he got down to 2min 26.4sec that he saw any signs of Moss dropping back, and Moss was timed at 2min 27.6sec.

Stirling Moss in his Lotus 18/21 Climax, he later retired from the race.

Motorsport Images

This showed the true Ferrari potential a bit sooner than Tavoni intended and von Trips tried to explain it away by saying he had no idea he was going so fast and merely wanted to get rid of Moss. He should have known that Moss sticks like the other type once it is there. With 2min 27.6sec in the bag Stirling came into the pits, grinning and making a rude sign at the Ferrari pit as he went by, and well satisfied at having pulled a fast one on all the other slow runners, for now Tavoni was awake to the trick and when he saw some British cars about to use Baghetti for a slip-stream tow along the pit straight he signalled the Italian to come in. Engineer Chiti did not see this and when Baghetti stopped he asked what the trouble was, to which Baghetti replied that he did not know. Tavoni came up and said he could go off again now, all the British cars were on the other side of the circuit.

With von Trips having made FTD unwittingly, Phil Hill went out and the Ferrari pressure was now really on; in successive laps he did 2min 26.1sec; 2min 26.0sec; 2min 25.2sec; and 2min 24.9sec and then came in and the Ferrari team sat back and said “There, any more fooling around by you Climax cars and we’ll go even quicker.” Moss having shown how to slipstream to good advantage everyone else was out looking for a Ferrari, but only Baghetti was going round and apart from being protected by Tavoni he was not yet going fast enough to be of much use, but he did provide practice for getting in close behind.

He was down to 2min 32sec, which was remarkably good for his first appearance in a big race, but the better Climax drivers were below this time anyway, and Graham Hill had done a brilliant 2min 29.1sec, unaided, which was just about the absolute limit for a British car on its own. The two works Lotus cars were going well, there being nothing to choose between Clark and Ireland on this circuit and it was good to see that Innes had recovered completely from his Monte Carlo crash, showing like Moss and the late Jean Behra that a top driver stays a top driver regardless of brief setbacks.

Phil Hill leads team mate Wolfgang von Trips in their Ferrari 156s.

Motorsport Images

During the following day the temperature rose steadily and once more practice was at 6pm, following a bout of Junior practice, and this time the road surface was beginning to show signs of melting in the sun. For a change this practice was viewed from the outside of the Thillois hairpin, which is the right-hand 60mph hairpin at the end of the long descent and leading on to the pits straight. At one time it was a really acute hairpin, but in the search for the fastest track in Europe the French club cut a new road on the inside of the hairpin, making it much faster, and leaving the old one as an escape route should a driver arrive too fast.

In dire emergency cars can go straight on down the main road towards Reims as an escape route, and during the two hours of practice it was remarkable how many people did use both these escape routes. The only way to find the absolute limit of braking from 150-160mph is to go beyond the limit, and Thillois, with its two escape routes was the place to try.

Porsche arrived for this practice, with their three old cars, one with an “L” on it as the substitution of de Beaufort for Herrmann was not fully organised. Bonnier did most of his practice in this car, even though it was meant for de Beaufort, so that the Dutchman got the times and the Swede did not get an official lap time. The two Serenissima cars were out practising, as also were May and Seidel in the two white Lotus cars. Jimmy Clark’s new works car was having engine trouble so he spent most of practice on the spare car, which was not as quick as his own, and Bianchi started off in the training car of UDT.

The other HP firm were in trouble for Surtees came by making a horrid noise and heading for the pits, with the engine broken in his standard Cooper, and later he reappeared in the modified one but was having trouble selecting gears on the Colotti gearbox. After yesterday there was little point in the Ferrari team wearing out their cars so neither Phil Hill, nor von Trips did any practice and Ginther did only a few laps to do some experiments.

Stirling Moss in his Lotus 18/21 Climax, he later retired from the race.

Motorsport Images

Baghetti, however, was out the whole time, going round and round, learning to motor-race amongst the “big-boys” and he was obviously learning well, for Coopers, Lotus and BRM cars were all pushing him around, outbraking him into the hairpin, taking him on the inside, sitting right behind him along the straights, and generally giving him a busy time, for he was lapping at close to 2min 30sec, which was a time that the better Climax drivers could comfortably keep up. As the evening wore on so Baghetti learnt, and by the end of practice he was beginning to give as good as he got, and at one time he had McLaren, Brooks and Graham Hill all round him, and the two BRMs really sorted him out, but next time round he forced his way into Thillois ahead of them, and left them on the wrong line.

Ginther went round in his own car in normal trim, which is to say, with two Perspex bulges over the carburetters in place of the gauze ones used earlier in the season, and then he had a curious humpty tail fitted to the car. This replaced the Perspex covers and extended right up to the top of the crash bar and instead of taking air from under the bonnet, the carburetters now drew air from behind the driver’s head. He did a few laps with this cowling bolted on and then stopped and had it removed, doing a few more laps with the normal twin covers, and could find no change in the performance of the car so the project was abandoned.

“Baghetti was out the whole time, going round and round, learning to motor-race amongst the ‘big-boys’”

Down at Thillois there was excitement when a black 403 Peugeot on Paris number plates appeared from Reims motoring towards Soisson, on the circuit and in the opposite direction to the racing cars! It had driven round the barriers unnoticed by the somnolent gendarmes and the man seemed to be on his way home.

He got about 200 yards up the circuit just as McLaren and Baghetti arrived and as the Peugeot was waved onto the grass by irate marshals the two racing cars went straight up the escape road, more in surprise than anything else. Three gendarmes pounced on the indignant Peugeot driver who did not seem to appreciate that the road was closed to traffic and he was last seen on his way to the Bastille. A new face appeared at the wheel of the UDT training car and this was JM Bordeu, the young Argentinian Formula Junior driver, and after a few laps he was going nearly as well as his team-mates, but it was only in the nature of a try-out for future reference by the UDT-Laystall group.

Willy Mairesse’s Lotus 21-Climax in the pits.

Motorsport Images

Moss did not look too happy with his Lotus, frequently opening out in the corner and then having to lift off again because the car did not respond as he thought it was going to, the handling being not what he wanted. With the 1961 rear suspension having a lower roll-centre than that used last year, and having different characteristics with its sliding-spline half-shafts against the solid ones, it would appear that Moss needed a 1961 front suspension to go with it. In short, he needed a new car. However, he seemed happy enough when he got in a little dice with Gurney and Salvadori for a few laps, but they were only going round in 2min 32sec. Practice ended with only one driver getting below 2min 30sec, that being Ginther, who did 2min 27sec, but it had not been for want of trying, for the whole two hours had been very busy.

Still the heat increased and on Friday everyone was preparing for another holocaust like 1959 as the day got hotter and the air more stuffy. The same time of 6pm to 8pm was reserved for the Grand Prix cars and this evening Mairesse was loaned the spare works Lotus, Clark’s car having been repaired, and the Ferrari team went out for a few laps each just to see that everything was all right. Ginther was the fastest with 2min 26.8sec, but it was obvious that they were not trying very hard, for they had no need to, the closest rival was Moss with his “artificial” 2min 27.6sec. and the nearest “honest” time was Graham Hill’s 2min 29.1sec.

Baghetti was going round and round, the object obviously being to give him driving experience and the opportunity to drive in close company with other Grand Prix cars, and this he certainly got for everyone was trying to use him for a “tow.” As he still had not broken 2min 30sec this did not worry Tavoni any more and he left him to the British, feeling that it was all good experience. ‘The Serenissima team were rather depressed with de Tomaso, and Trintignant drove it most of the time, which is why he was not given an official time for his own car, and young Lewis did not practise as he felt his unaided 2min32sec of the previous day was good enough for the circumstances.

Ferrari 156 driver Phil Hill waits in the pits.

Motorsport Images

As this final practice period closed there was a lot of dicing going on amongst groups of British and German cars and in all this trying McLaren, Clark, Ireland, Gurney, Brooks and Surtees all got below 2min 30sec, and needless to say young Baghetti was mixed up amongst them all, though his best time was 2min 30.5sec. The table on page 661 gives the practice times for all three days.

Saturday was a free day, the idea being to let the road surface settle a bit, but the sunshine became tropical and the tar melted even more. While the mechanics prepared the cars the organisations cooled themselves off with Champagne and on Sunday morning there was much relief when the temperature showed signs of not rising any more. The morning was taken up with two heats for the Juniors, both being won by Trevor Taylor in the works Lotus-Ford from Tony Maggs in Tyrell’s Cooper-BMC, and at 2:15pm the Grand Prix cars were wheeled down the track from the pits to the starting line, the drivers either going with them or walking on their own.

“Many of the drivers had literally, soaked themselves in water to combat the heat”

Many of them had literally, soaked themselves in water to combat the heat, so that they looked a pretty tatty sight, but the appreciative crowd cheered and clapped more in sympathy for what they knew was going to be a gruelling two hours sitting in an inferno than anything else. The biggest cheer went up when Moss appeared, in wet soggy overalls, and there was no doubt that the French crowd were more on his side than on anyone’s.

The three works Ferraris had had the Perspex carburetter covers replaced by the older gauze types, Lotus had removed the cockpit side panels and many cars had been fitted with slots and scoops in anticipation. of the tremendous heat. Also Porsche and BRM had taken precautions against flying stones, for which the Reims circuit is notorious when the tar melts, by fitting wire-mesh guards in vulnerable places such as carburetters, tops of windscreens and oil coolers.

Race

Wolfgang von Trips (#20) leads Phil Hill (#16), Richie Ginther (#18, all Ferrari 156) at the start of the race.

Motorsport Images

The grid line-up, see next column, was one of the biggest Championship fields yet assembled, showing that interest in Formula 1 racing is extremely alive.

For once Mr. Raymond Roche did not make a nonsense of the start and all 26 cars got away perfectly, the three Ferraris on the front row surging away together, but Moss was tucked right in behind them and crouching down behind his windscreen and really trying. Needless to say it was the three red cars that led down the hill to Thillois, but the blue Lotus of Moss was right behind them and the end of the opening lap saw the whole field stream by almost nose to tail, the leaders being in the order Phil Hill, Ginther, von Trips, Moss, Surtees, Clark, Ireland, Graham Hill, Brooks, Bonnier and so on.

At the end of the second lap things broke up a bit and the three Ferraris in the order Hill, von Trips and Ginther, and Moss were in the leading group, then came Surtees and Clark nose to tail, followed by the two BRMs and then Bonnier, Gurney, Ireland, Baghetti and McLaren practically touching each other, then Salvadori followed by Brabham and Mairesse. Already there was trouble amongst the tail-enders and both Lewis and Gregory pulled into the pits for attention.

On lap 3 Ginther was right on the tail of von Trips and Moss was doing wonders to stay with the red cars, there being quite a gap before Surtees arrived and behind the Yeoman Credit car there was a solid mass of cars comprising Clark, Hill, Ireland, Brooks, Baghetti, Bonnier, Gurney and McLaren, all going by as quickly as that. Collomb stopped at his pit and so did Henry Taylor, the UDT car having a petrol leak.

Richie Ginther at the wheel of a Ferrari Dino 156.

Motorsport Images

On lap 4 as they went round Muizon hairpin, before the long downhill straight to Thillois, Phil Hill still led from von Trips but Ginther got into a slide and spun, which let Moss by. Surtees was next along and in dodging Ginther’s car the Cooper took to the rough stuff and clouted a bank which bent a rear suspension member, so as the cars passed the pits there was quite a reshuffle.

The order was Hill, von Trips, Moss, Ginther but then no sign of Surtees, and it was not until the main pack had gone by that he appeared and motored slowly into the pits to retire. Brooks also went into the pits, his Climax engine overheating due to sitting close behind other cars, and he went out with a head gasket gone. Lewis was back in the pits, as was Gregory and they were joined by Burgess, so the mechanics had a busy time in the sweltering heat.

On lap 5 Moss was still holding third place and crouching down in his cockpit trying all he knew, but the two leading Ferraris were drawing away and Ginther was catching him up fast, but the initial sprint had carried him well away from all the other runners. Now the race began to settle in a pattern, with the first four places more or less settled, but the most almighty dice going on for fifth place. On this lap the order of the “second race” was Clark, Ireland, Hill, Baghetti, Bonnier, McLaren, Gurney, all nose-to-tail or side-by-side, the traffic being so thick as this lot rounded Thillois that it was surprising that nobody ran into anyone.

Almost the length of the pits straight behind came Brabham, de Beaufort and Salvadori, and then came the stragglers. Those at the tail end that were not in the pits could do little other than motor round and hope to keep going, and to keep an eye on the mirror for the time when they would be lapped. By one of those strange adjustments that only timekeepers understand, Moss was credited with the fastest lap on lap 2, in spite of the fact that the Ferraris were drawing away from him all the time, and the official bulletins had three goes at the right answer before they settled for 2min 30.4sec – 198.712kph. This meant that the Ferraris were lapping well below their limits and as they were way out in front already the race as such seemed to be over.

Phil Hill in his Ferrari 156.

Motorsport Images

On lap 6 Ginther got back into third place and the pattern was set, the only doubt being as to which of the Ferraris would win. Enzo Ferrari himself has little or no time for the Driver’s World Championship and merely wants a Ferrari to be the winning car, but the drivers had different ideas, so that when pre-race orders indicated that Phil Hill was not to win this event, there was some umbrage and in the opening laps he was obviously pressing on to show that when he relinquished the lead it was only to obey pit orders.

The battle for fifth place was as furious as ever, nobody having any real advantage, and on lap 8 when Phil Hill began to slow down and wait for von Trips, Baghetti moved up to third place in his group, behind Ireland and Graham Hill. On the next lap the BRM was pushed back and the order was Ireland, Baghetti, Clark, Hill, McLaren, Bonnier, Gurney, and so furious was this battle that it was beginning to take precedence over the race itself. At 10 laps Phil Hill led von Trips by 2 seconds, then after on 18-second gap came Ginther, with Moss 10 seconds behind him, but only 6 seconds later came the battle, and it was obvious that they were closing up on Moss.

“Moss was now slowing visibly and it could be seen that the pack behind him were catching him on braking”

Their order was now Baghetti, Clark, Bonnier, Hill, McLaren, Gurney, Ireland, this reshuffle being caused by Baghetti pushing Ireland onto the grass at Muizon, but one lap later and Ireland was back up behind Clark and Baghetti and out to get his own back on the Italian. This was a splendid free-for-all with every man for himself, although it was very obvious that the red Ferrari was the real bait that they were all attacking. Behind them Brabham was having a bad time being unable to get rid of de Beaufort, the Dutchman driving very wildly at times and nearly taking Brabham onto the grass with him. Scarlatti was in the pits with the Tomaso OSCA and Mairesse was in trouble with the works Lotus, while Lewis and Brooks had retired.

Moss was now slowing visibly and it could be seen that the pack behind him were catching him on braking, and on lap 13 as Phil Hill lifted off and let von Trips go into the lead, having made it obvious who he thought should have won the race, Baghetti and his keen followers were right behind Moss.

French GP, Rheims, 2 July 1961

Jim Clark in a Lotus 21-Climax leads Giancarlo Baghetti in his Ferrari Dino 156 and Innes Ireland in a Lotus 21-Climax.

Motorsport Images

Next time round von Trips led Phil Hill, while Ginther was still some way back, and in fourth place came Baghetti, with Clark and Ireland and the rest of them on his heels, Moss being in the middle of the group. His Walker-Lotus was in trouble with the brakes, the pedal feeling spongy and the braking uneven, but he was keeping going as best he could, staying in with the lads who were dicing for fourth place now. On lap 15 Tavoni gave his two leading drivers a sign which said “GINT,” meaning either “wait for Ginther,” or “let Ginther take the lead.” This sign came out on the next lap, and on lap 17 von Trips and Hill were given the “slow down” sign.

Behind this Ferrari procession poor Baghetti was having no peace, for now Clark and Ireland were making a concerted attack on him, and the three of them had pulled away slightly from Bonnier, McLaren, Moss, Graham Hill and Gurney, who were still in a tight bunch. Brabham had disappeared into his pit with reputed low pressure, but it may have been to escape from being run over by de Beaufort, and Bianchi had stopped with overheating, and Trintignant was in the pits with the Cooper-Maserati.

On lap 20, having been commanded to slow down, the Ferraris did so, but at the end of the lap it was Phil Hill who went by into the lead and von Trips drew into the pits with water coming out of his right-hand exhaust pipe. There was no need to look for the trouble, for water in the exhaust means only one thing and that is a ruined engine, so number 20 Ferrari was wheeled away and the race took on a new interest. Since the first appearance of the 120-degree Ferrari engine at Monaco they have not given a moment’s trouble and the last thing anyone contemplated was a Ferrari retirement, especially as they were not being driven to the limit.

Moss was having more and more trouble stopping his Lotus and was now at the back of the battle, which was now being resolved for third place, the order being: Baghetti, Clark, Ireland, McLaren, Bonnier, Gurney and Graham Hill, all as close as could be. On lap 19 Phil Hill had 14 seconds’ lead over Ginther, feeling quietly satisfied at being back in the lead again, in spite of Mr. Ferrari’s plans. Moss drew into the pits, the lack of braking becoming embarrassing, and it was discovered that the balance pipe between the two pads of the right-hand rear disc brake had fractured and was letting all the pressure, and fluid, escape.

Winner Giancarlo Baghetti leads in the Ferrari 156, while Lotus 21 driver Innes Ireland gets it crossed up.

Motorsport Images

Four laps had gone by while a new pipe was fitted and during that time, unbeknown to anyone a layer of molten tar that had centrifuged around the inside of the rims of the rear wheels, had run down to the bottom and coagulated. The wheels being alloy discs, this could not be seen and when Moss restarted back in the race he found a terrible vibration coming from the back end, so stopped next time round to check that the wheel had been tightened properly after the brake repair. It was all right so off he went again, but still had this vibration and after a few laps returned to investigate. It was some time before the lumps of tar were discovered and the vibration cured, but by this time he was many laps behind the rest of the field.

Phil Hill continued to lead Ginther by approximately 10sec, and Baghetti still had the Lotus pair all round him, Clark leading on lap 20 and Ireland being in front on lap 23, but there was never more than a few yards between the three of them. A little way back Bonnier was just leading McLaren, Graham Hill and Gurney, and on lap 23 Gurney suddenly shot to the lead of this group and set his sights on the Ferrari/Lotus duel, as if he had got his second wind. On lap 25 the gap between the leading Ferraris doubled as Ginther had another “moment” out on the circuit, taking a slip-road, but he was still 55sec ahead of Baghetti who was now being attacked by Gurney as well as the two Lotus boys.

The only other runner that was going steadily and not in trouble was Salvadori, but he had been lapped by the leaders already. The Porsche of de Beaufort had succumbed to his driving and retired with an oily mess all over the back of the car and a lot of smoke from underneath, and though Burgess, Taylor, Trintignant, Gregory and May were still running they were all much too far back to be of any consequence. Phil Hill was lapping quietly in 2min 35sec, and on lap 29 he had Moss just behind him, though naturally many laps in arrears.

On the previous lap Gurney had forged ahead of his group, and Bonnier had moved up to help him, the order being Gurney, Baghetti, Bonnier, Clark, Ireland, so the young Italian was still hard at it. Ireland was beginning to lose power, probably due to the engine swallowing a stone and he was dropping back very slightly, but Clark was still going strongly and up with the Porsches and the Ferrari.

On lap 29 Baghetti retook third place, followed by Bonnie

Jo Bonnier in a Porsche 718 leads Giancarlo Baghetti driving a Ferrari Dino 156 and Dan Gurney also in a Porsche 718.

Motorsport Images

r, Clark and Gurney, but then Clark passed Bonnier, and on lap 31 he was right alongside the Ferrari, the two cars passing the pits side-by-side. On the next lap it was Gurney who was alongside the Ferrari, and on the next time round Bonnier actually led the Ferrari, so that Italian boy was having a really rough time in his first big Grand Prix race. The remarkable thing was that he was more than holding his own against all these experienced drivers, giving back as good as he was getting and not making any mistakes under conditions in which a mistake would have been excusable.

On lap 34 he got the lead again, being now in third place overall, behind Phil Hill and Ginther, and though he held his position on lap 35 he had the two Porsches and the Lotus right there with him. On lap 36 Clark collected a stone on his nose from someone’s back wheel, which apart from being painful also broke the fixing of his goggles, so that he lost a lot of ground while he put on a spare pair that he had round his neck, and having once lost the pace of the Ferrari and the two Porsches he could not regain it.

The Ferrari pit had been confidentially giving Hill and Ginther the number of laps left each time they cruised by and the two red cars appeared regularly in just over 2min 32sec. At the end of lap 38 there was consternation for number 18 appeared on its own, which was Ginther, and Hill was seen to be stationary down at Thillois. He had spun on the wet tar and as Moss went by, the Ferrari and the Lotus had clouted each other.

This had caused Hill to stall his engine and the clump had bent the Lotus suspension, so Moss came slowly into his pit to retire, gaining some small satisfaction in being able to signal to the Ferrari pit that Hill had spun. Poor Hill was unable to get the engine going again on the starter and in the sweltering heat had jumped out and was pushing the car to try and get it started, in spite of the fact that the recent FIA rule forbids this under any circumstances.

Innes Ireland Lotus 21 Climax.

Motorsport Images

As if the passage of Ginther on his own was not bad enough, Gurney and Bonnier were on each side of Baghetti, with the American actually in second place. Next time round and Ginther headed for his pit pointing at the oil taken in the nose of the car. He was losing oil pressure and thought that maybe the level was low, but like his team-mate he too had forgotten the latest Grand Prix rules, for it is forbidden to take on oil once the race has started. Knowing this Tavoni waved Ginther away and he set off just as Baghetti appeared with his two silver satellites right behind him.

Clark and Ireland were now running spaced out, but behind them McLaren and Graham Hill were still dicing together, passing and repassing, and apart from these everyone else had been lapped many times. On lap 42 Ginther still led, but was keeping his fingers crossed for his oil pressure gauge showed a very unhealthy situation, and half-way round lap 41 things got so desperate that he stopped out at Muizon before the engine burst asunder.

“The whole hopes of the Scuderia Ferrari rested on young Giancarlo Baghetti, driving in his first World Championship race”

One can hardly imagine Baghetti’s thoughts as he and the two Porsches went by the stricken Ferrari, having already passed Phil Hill push-starting his Ferrari, but one can certainly imagine those of Bonnier and Gurney, who were now dicing with the young Italian for victory of the 47th French Grand Prix. Phil Hill got his engine started and in a very exhausted state rejoined the race in ninth place, behind Salvadori and a lap behind the leaders.

Now the whole hopes of the Scuderia Ferrari rested on young Giancarlo Baghetti, driving in his first World Championship race, and, in fact, the whole hopes of Italy rested on his shoulders. It seemed quite impossible that such a newcomer to big-time racing could go on battling against more experienced drivers without making a mistake of a missed gearchange, an error in braking, or a misjudgment of speed into a corner, or getting elbowed out of line by his superiors.

Stirling Moss in his Lotus 18/21.

Motorsport Images

Bonnier and Gurney now attacked with renewed vigour, for victory was in sight and on lap 41 Baghetti led by the smallest margin, and there were only 11 more laps to go. The whole of the vast crowd around the circuit now became alive, the pits and grandstands were in a fever and pit signals were unnecessary, there were three cars in a tight bunch and anyone of them could prove the winner. It was a battle to the death.

On lap 42 the Porsches were side-by-side, one each side of Ferrari’s long tail, on lap 44 they had the red car between them, but on lap 45 Baghetti was back in front again. Once more they made a concerted attack, and on lap 46 they were side-by-side and in front of the Ferrari. Now it seemed that they had got Baghetti sewn-up, but next time round and he was back in the lead, having gone by them down the straight to Thillois and outbraked them for the hairpin.

On lap 48 he was the meat in the sandwich once more, the three cars practically touching each other as they roared past the pits. On lap 49 Gurney dead-heated the Ferrari across the line, with Bonnier almost touching their exhaust pipes, and the crowd nearly died with excitement. On lap 50 Baghetti snatched the lead again, but Gurney was only inches behind, the wheels of the two cars being almost interlocked. The American was really fighting now, but the unruffled Baghetti was still holding his own in the most incredible exhibition of cool driving anyone could wish to see. Bonnier had dropped back and the reason was clear to see when he drew into his pit with smoke and oil coming from the rear of the car.

The Porsche engine had succumbed to the furious pace. With only two laps to go he was sent off to try and limp round to the end, but meanwhile Gurney was racing the Ferrari for the Thillois hairpin. He got the lead and held it up the straight towards the finishing line, crossing it with Baghetti right alongside him, but a few inches back, and together they disappeared over the brow and under the Dunlop Bridge to start the last lap.

The tension was terrific as everyone waited for them to reappear on the long straight down to Thillois, and as they shot out of woods and started the run downhill, at 150mph the red Ferrari was just leading. The silver Porsche gained slowly but surely and as they went into the braking area for the hairpin Gurney took the lead. Out of the hairpin they slid, with the Porsche leading but the Ferrari was right in its slipstream.

Giancarlo Baghetti in his Ferrari 156 closely followed by Dan Gurney driving a Porsche 718, takes the chequered flag for 1st position and his maiden win on his Grand Prix debut.

Motorsport Images

Up the final straight they came, with thousands of pairs of eyes from the grandstands and pits glued on the two cars. About 300 yards before the finishing fine the Ferrari suddenly pulled out and shot by the Porsche in one of the most perfect pieces of timing by Baghetti that would have done credit to Fangio himself. The roar from the crowd was terrific as the young Italian won the French Grand Prix by less than the length of a car. The Ferrari team were beside themselves, the Porsche team happy enough at having put up such a splendid fight, and the Chapman team more than pleased with their third and fourth places.

Bonnier struggled round to finish seventh, and the McLaren/Graham Hill duel was resolved as they crossed the line, in favour of the New Zealand driver. A very unhappy Phil Hill arrived a lap late, bringing Ginther in on the tail, and the Ferrari team drivers drowned their sorrows while the FISA protege was lifted from the car and water was poured on him to cool him off, for he had driven a harder race than anyone, having been attacked by all and sundry for the whole 52 laps, to say nothing of the three practice sessions.

This was motor racing, and Giancarlo Baghetti had arrived, even if he never wins another race, for he had ensured that the 1961 French Grand Prix will go down in history just as Mike Hawthorn did in 1953.

While everyone sank into heaps and searched for something cool to drink the Formula Junior lads came out to contest their final, and Tony Maggs won from Trevor Taylor, but as the Lotus driver had won both heats and the result was to be based on addition of the results of the three races he was a certain winner.