1960 French Grand Prix race report: Cooper-Climax revolution marches on

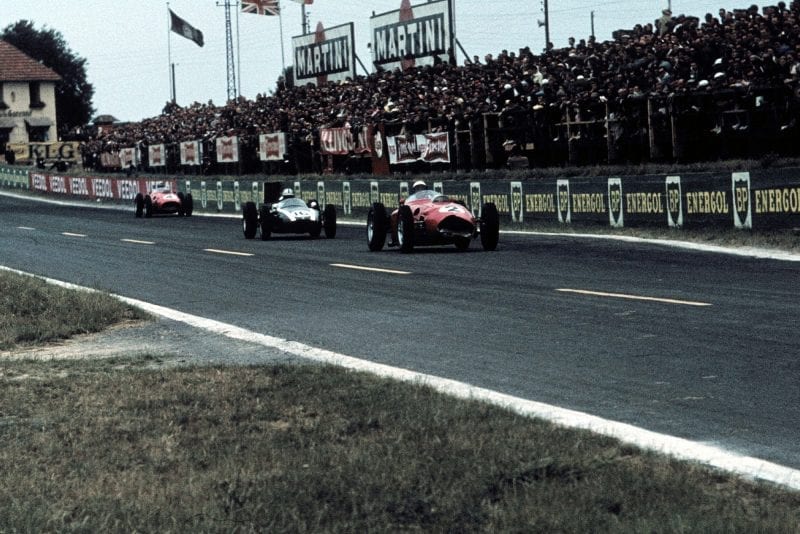

Jack Brabham leads home Olivier Gendebien and Bruce McLaren for a cooper-Climax 1-2-3; Ferrari's Phil Hill and Wolfgang von Trips challenge early but both fall to transmission failure

Jack Brabham takes his 3rd win of the season

Motorsport Images

The annual race meeting at Reims is always an exceptional one for it is characterised by a surplus of time, unlike some meetings, and the Automobile Club de Champagne can close the roads which form the permanent circuit very easily. In addition it is a meeting that is essentially one of high speed, the circuit being roughly triangular with very fast straights, one of them downhill and more often than not with the wind blowing downhill as well.

Qualifying

Practice began on Wednesday afternoon in a rather quiet way at first, for it was for Formula Junior cars, there being a Junior race due to be run on Sunday as a sort of “fill”. Only three cars turned out for this first practice so things were not greatly disturbed, though at 6pm the Formula 1 cars took the track and then there was some very high-speed motoring. The two works Coopers of Brabham and McLaren were off at once and went round together to look at the circuit and weigh things up. BRM had but one rear-engined car at the pits, for Graham Hill, though Bonnier and Gurney were standing around hopefully expecting their cars to arrive, which never happened.

There were three 1960 Ferrari works cars, all with front engines, and driven by Phil Hill, von Trips and Mairesse while Ginther was around and many people thought he should have driven instead of Mairesse. To the surprise of many, including the Scuderia Ferrari, Ginther went out in a Scarab, in place of Reventlow, while Daigh took out the other Scarab.

Phill Hill managed to get his Ferrari second on the grid

Motorsport Images

There was a lone Vanwall entry, driven by Brooks, and this was a new car, developed from the interim 1960 model which ran at Goodwood at Easter. This new car, still with front-mounted engine, had independent rear suspension and a new five-speed gearbox and the overall height and been reduced considerably, while the tail was small and round, with no headrest or scientific streamlined shape.

The new rear suspension was of double wishbone form, the top member comprising a long forward-running radius rod and a single-tube transverse arm, these two joining in a strong and well-made gusseted angle.

The bottom member was formed by an A-shaped wishbone and a short forward-running radius rod, pivoted to the apex of the wishbone, from which the cast alloy hub carrier rose vertically to join the top wishbone arrangement. Suspension medium was a coil spring and damper unit on each side, running inwards from the top of the suspension members to a chassis frame member.

This rear end, complete with new gearbox came from the design studio of Colotti, and the Vanwall gearbox, unlike the Walker one, was very small and compact. It was mounted behind the differential assembly, the drive running in at the bottom and out at a higher level, thus giving a low prop-shaft line and consequent low seating position.

A right-hand gearlever worked in an open gate with exposed interlock mechanism. Wheels on this new Vanwall were cast alloy, the front ones having thick spokes, somewhat similar to a Cooper (and both, of course, going back to the early 1920s and Bugatti) and the rear ones were solid disc with webs. The front wheels were bolted on and knock-off hubs were used at the rear.

The engine was still the beautifully made four-cylinder, with fuel injection, reckoned to be giving nearly 280bhp, but the wide frontal area of this new Vanwall was obviously going to need every one of those hp if it was to keep up with the small Lotus and Cooper cars. The Vanwall was wide of necessity, as it had fuel tanks mounted on each side of the scuttle, as well as a small one in the tail, this arrangement being dictated by weight distribution desires.

There was one private-owner out on this first evening, which was Piper with his front-engined Lotus, and fairly late in the session Ireland and Clark appeared with two of the works Lotus cars, the former having a long trunk alongside the body of the car, feeding air from an intake on the side of the nose to the Weber carburetters on the rear-mounted Climax engine.

It was soon obvious that the only team ready to go motor racing was the Cooper team, and after showing McLaren round for a few laps Brabham turned on the steam and was soon below 2min 20sec for a lap. Last year the fastest lap ever turned on the Reims circuit was achieved by Brooks with a Ferrari in 2min 19.4sec. during practice and the official lap record stood to Moss with the light green BRM of British Racing Partnership, in 2min 22.8sec, set up in the race.

Ireland managed to qualify his Lotus to 4th

Motorsport Images

To start practising nicely between these two bogey times showed that Brabham meant business and had got the Cooper going to his satisfaction. He was soon reeling off a number of fast laps and the time improved on each occasion until he left it at 2min 17.0sec and this was done before most people had got their engines properly warm, and before some people had even started to practise. Brabham was unobtrusively “doing a Fangio” and upholding his World Championship status, so that he could sit back and see if anyone could improve on 2min 17.0sec.

Needless to say they could not, though Phil Hill got round in 2min 19.0sec and von Trips did 2min 19.9sec and McLaren worked away at his driving and finally got down to 2min 20sec. The remarkable thing about this first evening was the apparent ease with which Brabham had set a lap time to stagger everyone and make them think, made all the more obvious by the way the others were visibly trying, in their efforts to catch up.

“Brabham was unobtrusively ‘doing a Fangio’ and upholding his World Championship status”

The lone BRM was having trouble with the hydraulic operation between the pedal and the clutch, so that Graham Hill did not have a lot of time in which to put up any sort of show. Bonnier had a lap or two in the car, but gave it back saying it was “horrible” for what one driver likes another invariably dislikes.

The Vanwall was having fiddling little bothers with the adjustment of the injection pump control, and Brooks had obviously forgotten what the car felt like in its glorious year of 1958, and the brakes which had never given trouble in the past were now suddenly playing tricks. The Scarabs were improving, Ginther getting down to 2min 36.1sec, but the four-cylinder engines were beginning to show signs of stress at being held on full throttle for such a long time.

Unlike the 1959 Reims meeting, this year’s race was being accompanied by cold, cloudy weather, with a biting wind, and hot coffee was in greater demand than iced beer, while there was no such thing as lukewarm Champagne. Thursday afternoon, same time, same place, the activity started again, and this time there was a goodly turnout of Junior cars, mostly British, but there was still not enough to fill the starting grid. With a big Junior race taking place at Monza on this day, none of the Italians were interested in Reims, while there were still some British entries hoping to do both meetings.

“Unlike the Formula 1 scene, where everyone had their eyes on winning the French GP, the Junior scene was quite without an objective”

Unlike the Formula 1 scene, where everyone had their eyes on winning the French GP, the Junior scene was quite without an objective. The race was going to be run in two heats, but no final, and stories were coming back from Monza about the Italians getting tough with flimsily made British cars, and the big Monza race was going on at this very moment anyway, so that Junior enthusiasts were not sure whether they ought to have been at Reims or Monza, and all round there was a vagueness in the air.

When the Formula 1 practice began again there was some heavy pressing-on, and in addition to those who were out yesterday the Yeoman Credit team were out in full force, with Gendebien, Henry Taylor and Halford as drivers, the Belgian driver’s car having a five-speed Colotti gearbox obtained from the Walker team. A third works Lotus arrived, being a brand new car, considerably modified in having the rear-mounted Climax engine canted over to the right (as is done on the Cooper) in order to get the Weber carburetters under the bonnet.

Brabham was once again on pole

Motorsport Images

Lotus have been dogged by poor carburation, inexplicable as they use the same engine and same carburetters as Cooper, and mounted more or less in the same position, and this change of engine position was an attempt to improve the carburation on the principle of “what works for Cooper should work for Lotus.” What they lack, of course, is a Jack Brabham amongst their drivers, but that is something that is difficult to achieve. This new Lotus was being driven by Flockhart, having his first drive in a rear-engined Lotus.

The BRM team was now complete, and Centro-Sud arrived with two Cooper-Maseratis, for Trintignant and Gregory, the former’s car having been considerably modified in the chassis department, by having its suspension lowered. Another Anglo-Italian combine to appear was the Cooper-Ferrari of the Scuderia Castellotti, being the car that appeared at Monaco earlier this season, with a Super Squalo four-cylinder Ferrari engine and Collotti-Walker gearbox mounted in a Cooper chassis. There should have been two of these cars, but only one arrived and was driven by Munaron. Only one Scarab turned out, the other suffering from engine trouble, and to complete the list there was Bianchi with Tuck’s 1959 Cooper-Climax, as run in the Belgian GP.

The Cooper team were still in full command, and to show that he had not been fooling around Brabham improved his best time of the day before, down to 2min16.8sec, once more demoralising the opposition, and before any of them had caught up with his first performance. Von Trips made a slight improvement on his time and also tried the Mairesse car, which the timekeepers overlooked, and credited the Belgian driver with the 2min 19.3sec recorded, and to confuse things even more Lotus were given the wrong number and Flockhart was circulating with number 26 on his car, as was Ginther in the Scarab, which may or may not have accounted for Flockhart’s best being 2min 52.2sec and Ginther’s 2min 31.4sec officially. The Lotus was called in and the number changed to 20, which later caused more confusion.

The Vanwall was getting sorted out, but new bothers started with the oil scavenging system, discovered too late to be caused by the return oil pipes being the wrong ones and collapsing under the suction, though looking all right from outside when the car was stationary. Graham Hill was getting into his stride and it was proving to be an interesting one, for he was well below the 2min 20sec “minimum,” with a time of 2min 18.4sec, and was, in fact, second fastest time overall. Phil Hill was playing about with great lumps of lead on his car trying to alter the weight distribution to give him the desired handling characteristics, and just before practice ended he got things really wound up and recorded 2min 18.7sec.

Whereas last year 2min 20sec was needed to have any hope of getting on the front row of the starting grid, this year it represented the slowest time with which to impress anyone, or even to be considered as having any hope of keeping up. McLaren made no improvement over his first day’s practice, but Ireland got down to 2min 19.5sec and joined the select band. Poor Piper’s racing was over when his Climax engine broke its valve gear and came out through the side of the head.

The final practice session was on Friday evening, and this time all the remainder of the Junior cars appeared, but in spite of organisers making a big thing about qualification and only the fastest 22 could start, there were only 23 cars in all that finally turned up, so the problem was an easy one. However, there was a flutter in the camp for at the last moment it was “discovered” that the fastest time of the previous day, given to Michael May driving a Fitzwilliam Lola-Stanguellini-Fiat, was wrong, and it had been Trevor Taylor who was fastest in his Lotus-Ford. To confirm this Taylor was fastest in the last practice period, with 2min 50.5sec.

Phil Hill talks to Ferrari mechanics before the race

Motorsport Images

The last Formula 1 practice was still cold and overcast, but all right for fast motoring, but this time Brabham did not improve on his previous times, though no-one got very close to him and the absence of Stirling Moss was very noticeable, he, of course, still being in hospital after his Spa crash but mending quickly. Brabham did a number of fast laps, looking so easy and confident, and also spent some time helping McLaren, who eventually joined the elite with 2min 19.6sec.

Phil Hill was still on great form and leading the Ferrari assault with some really forceful driving and improved his time to 2min 18.2sec to take second place from his BRM namesake, who could not reply to this challenge. Bonnier was down to 2min 19.8sec, and Gendebien did not quite get into the “upper class,” but nevertheless did a worthy 2min 20sec. Ireland was right up with them and made a considerable improvement, to 2min 18.5sec, while his team mate Clark was coming along nicely with 2min 20.3sec, fast and safe and not trying to impress anyone. There was only one Scarab out again, as engines were still giving trouble, and the timekeepers were also in trouble for Lotus had shuffled their cars and numbers and this did not show up in a vast sheet of figures.

“Phil Hill was still on great form and leading the Ferrari assault with some really forceful driving”

Yesterday, after changing Flockhart’s number to 20, so that the Lotus team were numbers 20, 22 and 24, Chapman found that he had his three Scottish drivers in the order Flockhart, Ireland, Clark, with the newcomer in the lead, so things were changed to Ireland, Flockhart and Clark, keeping their original cars, but Flockhart now being number 22. In consequence, the sheet of figures and times from which the final results of practice were “worked out” gave car number 22 with a time of 2min 19.5sec, and this was credited to Flockhart, whereas his actual best was 2min 23.4sec.

There was one final addition to the list of runners, for this last practice, and that was a third Centro-Sud Cooper Maserati, driven by Burgess, this having a new four-cylinder Maserati engine, improved on the previous design as far as detail work and moving parts were concerned. Saturday was a complete day of rest for the drivers and spectators, though the mechanics had plenty to do, but at least had every prospect of some bed before race day, and Reims began to fill to overflowing with racing enthusiasts from all over Europe. The unfortunate regular tourists who make Reims an overnight stop on their way to and from other parts, must have been rudely shaken by the vast milling crowds and cars of every shape and size.

Race

Phill Hill got the jump on Brabham at the start, but the Australian regained the lead soon after

Motorsport Images

Sunday morning was dry if not fine, for the cold wind was still blowing and the circuit had a dull appearance, compared with what is usually experienced at Reims. Under normal hot weather conditions of July it is one of the more colourful Grand Prix scenes, the long grandstand and pits a vivid scene, and the golden cornfields shining in the sun, though for the drivers there is usually the hazard of melting tar on the road. This year the scene was drab but the conditions for racing were good. To encourage people to hurry over their lunch and get to the circuit in good time for the 46th French Grand Prix the Junior drivers had a 10-lap race to form Heat 1 of their event, starting in order of practice times, which took place before the Grand Prix.

The grid for the Grand Prix was arrayed in the usual rows of three-two-three, but in spite of obvious errors Mairesse was in row 2 and Flockhart in row 3. The start was short of three cars, for the two Scarabs were withdrawn, having used up all their engine spares, and Piper had no spare engine.

1. Brabham (Cooper) 2min 16.8sec

2. P.Hill (Ferrari) 2min 18.2sec

3. G. Hill (BRM) 2min 18.4sec

4. 20 Ireland (Lotus) 2min 18.5sec

5. Mairesse (Ferrari) 2min 19.3sec (2min 21.6sec)

6. von Trips (Ferrari) 2min 19.4sec

7. Gurney (BRM) 2min 19.4sec

8. Flockhart (Lotus) 2min 19.5sec (2min 23.4sec)

9. McLaren (Cooper) 2min 19.6sec

10. Bonnier (BRM) 2min 19.8sec

11. Gendebien (Cooper) 2min 20.0sec

12. Brooks (Vanwall) 2min 23.3sec

13. Bianchi (Cooper) 2min 23.6sec

14. Halford (Cooper) 2min 23.6sec

16. Gregory (Cooper-Maserati) 2min 24.3sec

17. Trintignant (Cooper-Maserati) 2min 24.7sec

18. Munaron (Cooper-Ferrari) 2min 31.3sec

19. Burgess (Cooper-Maserati) 2min 36.7sec

N.B. – Correct times for Flockhart and Mairesse are given in parentheses

With Cooper, Ferrari and BRM on the front row, Lotus and Ferrari on the second row, and Ferrari, BRM and Lotus on the third row there was the makings of an outstanding race which anybody could win. During practice, the starter had been telling everyone that contrary to the regulations everyone had to be off the track at the 30-seconds signal, and at any time from then until zero he would be liable to give the starting signal, giving it as and when he considered everyone to be ready. He stuck to his word and gave it about 28 seconds before it was due and unknown to him Graham Hill could not get his BRM into gear.

Everyone roared off and there followed an awful commotion, as can be imagined with one of the cars on the front row not moving. Those immediately behind dodged the stationary BRM, but Trintignant came charging through the exhaust and rubber smoke and rammed the BRM really heartily, putting it sideways on with its back wheels all out of line. Meanwhile Bianchi had swooped to the right and hit the Vanwall, which had in turn caused Halford to spin. Bianchi’s Cooper spun across the road and landed up by the pits, pointing the wrong way, Halford was stalled across the grid, Graham Hill was still sitting there helplessly and Trintignant limped his bent Cooper into the pits. Halford and Bianchi were restarted and joined the race which was now streaming round the back of the circuit towards Muizon hairpin.

“Halford was stalled across the grid, Graham Hill was still sitting there helplessly and Trintignant limped his bent Cooper into the pits”

As the leaders came down the hill towards Thillois corner there was clearly nothing to choose between the leading Cooper and the Ferraris, and still with very little gap between the cars the field came roaring up through the cutting formed by the pits and grandstands, under the Dunlop bridge and away on their second lap. For what it was worth the order was Brabham, Phil Hill, von Trips, Gurney, Bonnier, Ireland, Mairesse, Gendebien and McLaren, followed by the rest but all the first ten or twelve cars were so close that anything could happen.

On the second lap there was some shuffling around, but they were still either nose to tail or side by side and the timekeepers decided that out of the whole bunch of cars going by at150 mph von Trips had made a new lap record, in 2min 19.6sec. On lap 3 things broke up a little, for Brabham had a slight lead over the two Ferraris of Hill and von Trips, who were almost touching. Then came Ireland and Bonnier equally close, Gendebien on his own, followed by Mairesse, McLaren and Gurney, but even so such gaps as there were between cars could not be timed by a hand stopwatch.

Hill snatched the lead back and led until lap 5

Motorsport Images

On lap 4 Phil Hill got by Brabham, and the Ferrari led the Cooper past the stands, with von Trips right behind, and in spite of this Brabham was given a new lap record in 2min 18.8sec, so the pace was obviously as hot as it looked, with lap speeds of over 133mph Brooks in the Vanwall had been sitting at the end of the leading group and at the end of lap 4 he pulled into his pit to complain of a noise or vibration in the back end; nothing could be found amiss, in spite of the slight collision at the start, and he set off again. Burgess also called into his pit.

On lap 5 Brabham was back in the lead, but on lap 6 it was Phil Hill again, and so it went on, with von Trips always in third place and never more than a few lengths behind. The two Ferraris really had the Cooper at bay this time, but the Climax engine was giving as good as it got, and lap after lap the three cars went round almost touching; in fact, at one time they did touch, and Brabham looked in his mirror on feeling a bump, just in time to see Phil Hill’s Ferrari rising up on its back wheels with its mouth all twisted, having rammed a rear wheel of the Cooper.

Brooks was back in the pits again on lap 6 still complaining, and in again on lap 8 to retire, even though nothing could be found wrong, and Burgess too was making a number of calls to have adjustments made. The battle up the front went on and on, first the Cooper leading, then the Ferrari, then the other way round and then side-by-side, always with von Trips keeping up the pressure on their tails. Brabham was having a really hard time and when Hill took to the outside “escape road” at Thillois then von Trips was quickly in second place to keep the Cooper worried.

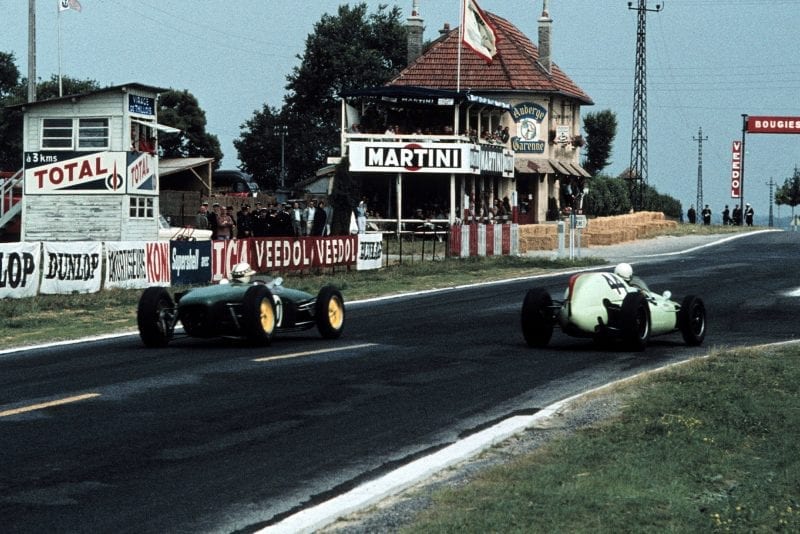

This was motor racing at its best and no high-speed procession, and any number of times the two leading cars would disappear over the crest after the pits, and under the Dunlop bridge, absolutely wheel-to-wheel and neither driver intending to give way. Behind this wonderful dice there was just as much activity going on, for the Ireland vs Bonnier duel had been caught up by the Gendebien vs McLaren battle, and for a while the foursome became very intense, but not for long as Bonnier’s oil pressure was sagging.

On lap 12 he called at the pits to take on oil, and this left Ireland just leading Gendebien and McLaren, but the Belgian obviously had ideas about improving this situation. Gurney and Mairesse had been having a nose-to-tail for eighth place, but on lap 15 this finished for Mairesse coasted to a stop near Thillois with no drive between the engine and the gearbox, and he rather pointlessly began to push the car back to the pits.

On lap 57 Gendebien was more than just alongside Ireland, as he had been for quite a time, he was actually in front, even though it was only by a matter of two feet, but in this race, the way it was going, that was quite a lot. On lap 18 Gurney drew into the pits to retire with a broken engine, and Munaron was already pushing the Cooper-Ferrari home, it having expired out on the circuit. On lap 19 Hill and Brabham came up the finishing straight side-by-side, and the Ferrari led by a few inches, with von Trips still right in their slipstream just over half a minute later Gendebien and Ireland appeared in a similar position, with McLaren in their slipstream, and the pace was just as fast as ever and nobody was giving in.

After these two high-speed groups there was another gap and then Henry Taylor came by, going well in the second of the Yeoman Credit Coopers, followed by Clark and Flockhart, while Greogry dropped out at this point to call at his pits for repairs. The remaining three cars, the BRM of Bonnier Halford’s Yeoman Credit Cooper and Burgess in the Cooper-Maserati had all been lapped, and Bianchi had just disappeared out on the circuit with the transmission broken in Tuck’s Cooper.

Gendebien and Ireland fight it out on the back straight

Motorsport Images

On and on went the leading cars, Brabham fighting the Ferraris all the way and the red cars doing all they knew to grind the little green car into the ground. Although they could not get rid of it the two V6 engines turning over at 8,200-8,400rpm were certainly drowning the sound of the Climax engine at 6,800rpm as they went round the circuit only feet apart after more than too miles of racing.

At half-distance, 25 laps, nobody round the circuit knew the answer to this battle, though it was likely that Brabham knew inwardly, for he had now led for six laps in a row, which was really an achievement under these conditions, and the three of them had increased the gap between their group and that for fourth place, to 64sec, and Gendebien, Ireland and McLaren were the only ones that had not been lapped by the leading trio.

As if to indicate that he had got the better of the two Ferraris, Brabham set a new lap record on lap 25 in 2min 17.5sec, a speed of 217.354kph (approx 135mph). Bonnier had given up at the pits with a ruined engine, and Gregory, Halford and Burgess were now two laps or more behind the leaders. On lap 28 Brabham was still leading and there were signs of a measurable gap between him and von Trips and Hill, who were still side-by-side.

“On and on went the leading cars, Brabham fighting the Ferraris all the way and the red cars doing all they knew to grind the little green car into the ground”

On lap 29 Brabham was a visible 5sec in front as they came up towards the pits, followed by von Trips and Phil Hill. As the American got to the pits the input bevel between the engine and gearbox broke and he freewheeled by at high speed, trying to stop before he left the pit area, which he just managed to do, but it was the end of a gallant run. Behind came Gendebien and Ireland, still side-by-side, with the Belgian just ahead, and next lap it was Ireland in front, now in third place after Brabham and von Trips had gone by.

On lap 31 Brabham arrived on his own and it was all over, for von Trips was coasting down to Thillois his transmission broken in the same way as Mairesse and Hill, and Ireland was now second. Gregory was back in the pits for more work, and there were only four cars on the same lap. Breathing a great sigh of relief Brabham could now tour round on his own nearly 1.5min ahead of his nearest rival, who was once again Gendebien, for the Lotus/Cooper battle was still waging, with the ever-present McLaren just behind them.

On lap 34 the race took another change, for Ireland came into his pits with his left front wheel at an odd angle as part of the Lotus suspension had broken, this being a ball joint obtained from a “specialist manufacturer,” normally designed for a production saloon and being used on a Grand Prix car! This left McLaren doing battle with Gendebien, and the old and new Coopers passed and repassed round the circuit, the works car getting ahead down the hill to Thillois but being outbraked by the Yeoman Credit car. As Brabham was touring round, at a mere 130mph average on his 41st lap Ireland was bodged-up and sent off again to continue slowly and finish, just ahead of the two Centro Sud cars which were back in the running after pit stops.

Ferrari’s Mairesse gives Vanwall’s Brooks a lift back to the pits

Motorsport Images

About this time Flockhart put on speed, getting the hang of the rear-engined Lotus and he began to catch Clark who had been running consistently and sensibly in fifth place behind Henry Taylor who was shining as the “new boy” of the race, now in fourth place after the various retirements. All Brabham had to do was to tick off the laps and win a very well-deserved race, but behind him there was a different story, for McLaren was not going to give in to Gendebien, Le Mans winner or no Le Mans winner, and they were still passing and repassing, on one lap the lead actually changing three times between leaving the pits and appearing in sight again, but always Gendebien managed to lead across the line.

On the penultimate lap McLaren was making a desperate bid to keep in front on Thillois hairpin, when he overdid his braking and had to take the slower escape route so that all was gone, and Gendebien was safely in second place for one more lap and to the end of the race. Flockhart caught his team mate and just failed to pip him to the post, the two cars arriving side-by-side. Such was the terrific pace in the first-half of the race that even though he had slowed up considerably towards the end, Brabham completed the 415 kilometres in well under two hours, thus infringing an FIA ruling about race lengths and times for World Championship events, not that anyone worries too much about FIA rules these days.

While the Grand Prix teams packed up and went home the Junior drivers appeared again for another 10-lap wheel-to-wheel dice, and somehow it was rather like watching Formula 3 racing all over again, proving that close racing is not the only desirable thing in successful motor racing. However, they all looked like little Grand Prix cars and made nice rasping noises, but more important it was an opportunity for drivers to do some real racing amongst themselves, and that in itself is desirable.

Brabham takes his 3rd consecutive win

Motorsport Images

Reims Ramblings

- Even though the Vanwall never performed very well, a surprising number of people enjoyed seeing a properly designed and built Grand Prix car once again.

- Before the race lots of drivers, officials and trade men were interviewed by a journalist and asked who they thought would win, the answers appearing in a daily paper. Opinion was divided between a dead cert for Brabham and Phil Hill. We liked Dan Gurney’s brief reply “Dan Gurney in a BRM”

- Graham Hill has now done everything. He retired virtually on the finishing line of the Belgian GP and on the starting line of the French GP.

- Is it true that Chapman was seen learning to play the bagpipes in order to call his “all Scots” team of drivers around him? He was certainly seen wearing a Tam o’Shanter.

- When the Scarab team packed up to go home a lot of people were “feeling very sorry for them “- wonder why these people did not feel equally sorry for Connaught, Gordini and Bugatti when they had to withdraw from the fray? Not dollar-worship surely!

- What a credit to motor racing is the turn-out of Trevor Taylor’s Junior Lotus-Ford. Lots of more famous cars and teams could well study this equipe to see that it can be done.

- We wonder which of the English visitors were behaving like Teddy Boys in Reims on the night before the race, and again on race night. Of course, they may have been Teddy Boys, they were certainly English, unfortunately.