1953 French Grand Prix: Hawthorn wins 'Race of the Age'

Ferrari's Mike Hawthorn emerges victorious from a close-run finish in the 1953 French Grand Prix at Reims

Motorsport Images

Reims, Sunday, July 5th.

This year the French Grand Prix returned to Reims and a meeting was planned which had the makings of being the finest of the century, but due to had organisation and mismanagement one way and another it very nearly proved to be the biggest flop of the century. The Automobile Club de Champagne, under the direction of Raymond Roche, spent over £100,000 on preparing the Reims-Gueux circuit for a fiesta of motor racing never before imagined. Not content with holding the 40th French Grand Prix, they aimed to steal some of the allure of Le Mans by holding a 12-hour sports-car race beforehand. This race was to be run from midnight Saturday until midday Sunday, and three hours later the French Grand Prix, for Formula II cars, was to run over the same circuit.

For the third year running the circuit was altered, a new road being built to make the total length up to 8.317 kilometres, the cars now having a much longer run on the downhill straight leading to the Thillois hairpin. In addition to altering the shape of the circuit extra pits were built, a tunnel under the track allowed the largest of lorries to pass, a new press stand was erected from which all possible activities could be viewed, and numerous restaurants and a “Dunlop-tyre” bridge just after the start as at Le Mans were added. All the improvements, involving much high-pressure work, resulted in a truly wonderful circuit appropriate for the occasion planned.

The entry for the sports-car race was very similar to that at Le Mans, though not so large, while the Grand Prix itself had all the usual runners, being a World Championship event. The first setback at this meeting, which was going to prove to be full of them, was the announcement to competitors in the 12-hour race that there had not been time to supply refuelling tanks and hoses and they would have to do the best they could.

Having read in the regulations that refuelling systems would be supplied, there was much hurried searching for funnels and drums. Throughout the practice periods there was a peculiar air of reluctance to get under way on the part of the competitors of both categories. Cunninghams were out in full force and going quickly on the first day as was the Moss–Whitehead works Jaguar and the Abecassis–Frere Jaguar-engined HWM, but Gordinis were absent as were the lone works Ferrari and the Talbots, while in the Formula II practice only the three Gerard’s Cooper-Bristol and Rosier’s Ferrari were running.

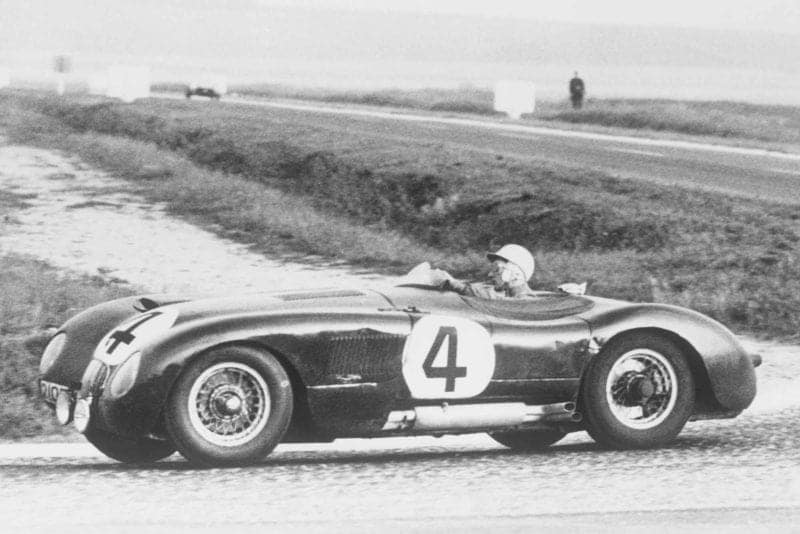

Villoresi chases after his Ferrari team-mate Hawthorn

Motorsport Images

On the second day there were still no Italian machines, though most people were out for the sports-car practice, which continued until midnight. Towards the end of the dark period the 1953 Cunningham or Fitch-Walters and the works Jaguar were proving the fastest, but during the last half-hour Behra and Lucas arrived with the new 3-litre Cordial and proceeded to put up times faster than anyone had done in the dark, and nearly as fast as the others had done in daylight.

On the last day of practice things returned to normal and first of all the sports cars hail a final hour in which to make sure everything was ready. Up to this time the Ferrari entry of Villoresi-Hawthorn had not materialised, but then it appeared and proved to be the 4.5-litre coupé that Ascari and Villoresi had driven at Le Mans, only it was to be driven by Maglion and Carini.

“After one or two inspection laps Maglioli played havoc with the sportscar lap record, beating everyone fairly comfortably on his first outing with a works Ferrari”

Among the regulations was one stating that no driver was allowed to drive after 9 am on Sunday morning if they were intending to start in the Grand Prix, so naturally the Ferrari team drivers were ruled out. After one or two inspection laps Maglioli played havoc with the sportscar lap record, beating everyone fairly comfortably on his first outing with a works Ferrari. It will be remembered that he won the Targa Florio with a Lancia and has done most of his driving with that make.

Qualifying

The sports-cars having been put away until midnight Saturday, the Formula II cars had their final practice and Ferraris and Maseratis were out in full force anti the practice battles we are becoming used to proceeded. All the faster times were an improvement over the sports-car record and it was Gonzalez who appeared to have the upper hand, but then Ascari and Villoresi dealt with him severely, only to have the Argentine take Bonetto’s Maserati and equal their times.

Outwardly neither of the teams had changed their cars since the Belgian Grand Prix and it was surprising that Ferraris could challenge the speeds of the Maseratis, but with two hairpin bends, requiring really heavy braking the Ferrari brakes were making up for a slightly inferior maximum speed. Although practice had been slow off the mark it finished at a peak with the sports-car race art open one between Cunningham, Jaguar, Gordini and Ferrari, and the Grand Prix with Ascari, Gonzalez, Villoresi, Fangio and Farina having only 1.3 seconds between the fastest and the slowest. Of the new boys Hawthorn made a better time than Marimon, while of the private owners Graffenried beat Rosier. Behind came the rest, led by Bira driving a works Connaught, and Gerard’s Cooper-Bristol—thanks to some quick laps put in by DA Clarke.

The Talbot Lago of Roiser/Giraud-Cabantous en route to 2nd place

Motorsport Images

Sports car race

As midnight approached on Saturday the whole of the pit-area was superbly floodlit, bands played, fireworks were let off, cabaret turns were performed on open-air stages and the restaurants and stands were full to overflowing. Starting a race in the dark was indeed a novelty to the public but the drivers of the faster cars were not looking forward to it, for a Le Mans start at 4 o’clock in the afternoon is hair-raising enough and the added handicap of plunging out of a pit-area like daylight into the pitch black of midnight was not a comforting thought.

Officially there was no general classification in this race, though naturally everyone was interested in the team that was going to go the farthest distance in the 12 hours. There were three categories, the first being up to 750cc, the second 750-2,000cc and the third over 2,000cc, so that there were to be three races and three winners.

That was officially, but generally speaking the Le Mans atmosphere had so invaded Reims that a general classification was expected. As at Le Mans the cars lined up in order of engine size with the drivers on the opposite side of the road and a quick glance down the line showed two Cunninghams, both open models, the new one driven by Fitch-Walters and the old one by Cunningham-Johnson, three Talbots as at Le Mans driven by Rosier-Cabantous, Levegh-Meyrat and Mairesse-Grignard, the 4.5-litre Ferrari of Maglioli-Carini, a 4.1 open Ferrari of Hill-Chinetti, the Moss-Whitehead works Jaguar, the Ecurie Ecosse, Jaguar driven by Scott-Douglas and Sanderson, a French 120C of Roboly-Simone, the Abecassis-Frere HWM with transverse-leaf ifs, and torsion bar de Dion rear, and two Gordinis, the 3-litre of Behra-Lucas and a 2.5-litre of Trintignant-Schell.

On account of a supercharger Constantin’s Peugeot 203 was in this group, which comprised category three. ln the middle class were the two Le Mans Bristols, bravely having another go, driven by Macklin-Whitehead and Fairman-Wilson, three assorted Gordinis, Mieres-Guelfi aud Layer-Rinin with two open versions of the 2-litre and Bourelly-Creapin with a 14-litre coupe.

Clarke and Scott-Russell were driving Gerard’s Le Mans Fraser-Nash, the owner running in the Grand Prix, Salvadori and Crook with the works Fraser-Nash coupe, two 2-litre Ferraris, a coupe driven by Picard-Pozzi and an open one by Legenier-Rubirosa, while Said’s blue and white 1,350cc Osca made up the class. Naturally the 750cc class was especially for French care and had mast of the Le Mans competitors running, with D.B., Panhard, Monopide, Renault, and V.P.-Renault, making a total of fifteen in this class.

Rising star Moss on his way to victory

Motorsport Images

It would have been nice to have seen a specially prepared Lotus-Austin having a go at this French monopoly. It is doubtful whether more than two drivers saw the flag fall, but they all got away and the race was on, with Villoresi in the Ferrari coupe soon going into the lead, followed by Behra (Gordini), Walters (Cunningham), Trintignant (Gordini), Moss (Jaguar), and Abecassis (HWM). Mieres led the 2-litre class, ahead of the other works Gordini and the Fraser-Nash coupe went out with clutch trouble. Drivers soon got used to the darkness and the Ferrari drew away from the rest of the field, while Behra came in with a flat rear tyre. It was found that the new car was too low for the jack, when the tyre was flat, and the whole staff tried lifting, but to no avail; eventually another jack was produced and the wheel changed, the car now being way back among the 2-litre class by the time it restarted.

By 1am things had settled down, the Ferrari being still farther ahead, followed by Trintignant, Walters, Moss, Abecassis, and Rosier with the first of the Talbots. The leading 2-litre Gordini had broken its accelerator pedal, letting the Loyer-Rinin car take its place, while Plantivaux and Bruwaere were leading the babies with one of the super-streamlined Panhards. Graham Whitehead retired one of the Bristols with a broken clutch before Macklin had a chance to drive, and Roboly’s nice new Jaguar ran a big-end.

“Fuel was spilt everywhere and no one caught fire, by a miracle”

Just before 2.30am pit-stops for fuel and new drivers began and at one end of the pits the marshals allowed only two mechanics to work on the cars, while at the other end marshals were allowing three. Officially the rules said that one mechanic could refuel and while he was doing that two others, or one and the driver, could work on the car, but no one was too sure and it was soon clear that few of the marshals had had practice at supervising long-distance race pit-stops. However, nobody bothered too much and everyone refuelled and changed drivers, fuel was spilt everywhere, no one caught fire, by a miracle, and the numbers around the cars depended on the nationality of the crew.

The leading Ferrari continued to retain its lead, except during the pit-stop reshuffling, and Carini took some time to get into the stride of Maglioli but by 3am he achieved it near enough. Before handing over Maglioli had made fastest lap in 2 min 42.8 sec, a speed of 184.585 kph, which would have put him in the second row of the Grand Prix. line-up. The Ferrari now seemed quite uncatchable and sounded perfectly healthy and the order in Class 1 was the Ferrari, followed some way back by the new Cunningham, Trintignant still driving the 2.5-litre Cordial, ‘Whitehead having taken over from Moss on the Jaguar, Frere driving the HWM, and Rosier driving the leading Talbot single-handed. Loyer and Rinin were still leading the 2-litres and the Chancel brothers had now taken the lead in Class 3 with the second streamlined Panhard.

The Constantin/Poch Peugeot would finish 13th overall

Motorsport Images

According to the regulations lights had to be kept on until 5 am irrespective of weather conditions and when the Ferrari went past at 4.30 am with no lights it was quite obvious that it was asking to be disqualified. A visit to the Ferrari pit to hear what the organisers had to say was imperative and as Charles Faroux, the Race Director, approached he had ” disqualification ” written all over his a face.

Before he reached the pit Cornet’s Panhard coupe went by without any lights, as did several DBs, the French-owned 2-litre Ferrari, one of the Gordinis and many others on sidelights only. The “disqualification” changed to a warning and the pit waved frantically to Carini to put the lights on again, as did all the other offenders, while Faroux gesticulated to those on sidelights, and nobody really knew whether the regulations meant sidelights or headlights.

Returning towards his office Faroux met Divo, the Assistant Race Director, and at that point the Ferrari came in for a pit stop. It was refuelled and Maglioli got in, and then fuel gushed out of the filler onto the ground. Many hands pushed the car clear of the spilt fuel, the engine burst into life and Maglioli was back in the race. This was 4.40 am and as he left there were no rear lights showing, while to those behind the car, including the Race Director, the car appeared to have been push-started.

Without more ado a meeting of the marshals was called and five minutes later the loudspeaker announced that “no more lap times would be taken for Ferrari No. 18 as it had infringed numerous regulations.” No mention was made that it had been disqualified, merely that no more times would be taken. It was now nearly three laps in front of the second car and going at the same furious pace.

Stirling Moss takes the chequered flag in the supporting sportscar race

Motorsport Images

Ugolini, the pit manager, was soon at the Director’s office to find out what rules had been infringed and a furious argument started, which went on for over 1 hours. From this point the race turned into a farce as partiality had been shown over the interpreting of rules and, much more serious, the organisers flagrantly ignored one of the most important rules of the International Sporting Code. As Faroux stated to Ugolini, a decision had been made; why or how or whether it was justified was another matter which could be discussed, but the actual decision to stop taking times for the leading Ferrari could not be altered. When a car is disqualified, for whatever reason, it must be stopped by the Race Director with a black flag and the number of the car concerned. This was not done and the Ferrari continued unchecked, while the loudspeakers, at 4.50 am announced that it had completed 100 laps of the circuit.

“The public were screaming abuse and calling for the reasons for the uproar”

The rights or wrongs of the disqualification depended entirely on the statements of the marshals concerned and when questioned more closely by Ugolini these statements began to vary. For example, those behind the car said it left without any lights, those in front said the headlights were on; those behind said the car was push-started, those beside the car said Maglioli pressed the starter, though no one was sure whether the car was still rolling or stationary at the precise moment. The question of the number allowed to work on the car arose again and it was clear that opinions or interpretations of the rules varied, but still the Ferrari was allowed to circulate; nothing was said about putting all the lights out before 5 am!

After a while “Lofty” England appeared on behalf of the Jaguar that was now officially leading, to suggest that the Ferrari be stopped if it was out of the race, as Moss was needlessly racing with it, thinking that it was still leading. Roche produced a black flag which he gave to Divo, who in turn produced a number 18 which be gave to Faroux; meanwhile the public were screaming abuse and calling for the reasons for the uproar. Faroux with the number and Divo with the flag waited for the Ferrari to appear and first of all showed them to a red Panhard coupe and then to the 2-litre Ferrari coupe.

Moss takes the plaudits, flanked by his parents

Motorsport Images

When Maglioli finally appeared there was a distinctly unassured air about the Race Director, and as the car passed he held up the number and pointed to the car while Divo kept the flag by his side. Naturally Maglioli did not stop and a lap or two later Divo went down to the beginning of the pit area and waved the black flag, but with no number, so again Maglioli did not stop. By now the whole affair had got completely out of hand and the officials were all for sitting down and forgetting the whole incident, but Ugolini would not have it and continued to keep the pot boiling.

No more official attempts were made to stop the Ferrari and just before 5.30 am, amidst an uproar from the public, the Ferrari pit signalled Maglioli to come in, which he did immediately, accompanied by a continuous chant of sympathy from the crowd, some of whom proceeded to pluck the decorative flowers from the grandstands and throw them on the car as it stopped. Maglioli justified his action of not stopping before by simply quoting the International Sporting Code, pointing out that a number on its own meant nothing, neither did a black flag.

This utter farce and mismanagement on the part of the officials caused much of the interest of the race to die away, the crowd began to disappear and go to sleep, and the remaining hours dragged heavily. While all this had been going on Fitch had crashed the new Cunningham while in the lead, writing it off completely, Schell had pushed the leading Gordini in with its starter motor permanently locked to the flywheel, the H.W.M. had broken its rear suspension and pit stops continued, with fuel splashing about everywhere, cars being pushed about, more than three people working on cars, depending on which end of the pits they were at. What had been a first-class race had turned into a shambles.

As those people who had been to bed began to filter back to the course after breakfast it was seen that Moss-Whitehead were lending with the Jaguar, followed by Rosier-Cabantous in the Talbot and Cunningham-Johnson in the Cunningham in Class 3, Loyer-Rinin were still leading in Class 2 from Fairman-Wilson in the Bristol and Picard-Pozzi in the Ferrari coupe, while many of the little cars were still going round, the Chancel brothers in the lead.

Moss stands to attention for the national anthem

Motorsport Images

Little of the daybreak excitement was known to them and no official announcements were made, so that opinions could only be gathered from hearsay and various improvements were made to the actual happenings, by the sleepers. Ferraris finally packed up and went home to bed threatening to return to Modena and not run in the Grand Prix, while Carini started the coupe on the starter and drove it round the back of the pits, unintentionally disproving any stories about the car being unable to be started other than by pushing.

As the heat of the day approached and the hours to midday ticked slowly away it was becoming rather obvious that the experiment of starting a race at midnight was not a good one, from the point of view of those keen ones who stayed up time whole time. Also, the much advertised music and dancing that was supposed to go on all night had fizzled out before the race even started and as Moss brought the dark green Jaguar in to the finish he was loudly acclaimed by the crowd that was beginning to assemble again for lunch. Cabantous finished second in time works Talbot, followed by Johnson in last year’s Cunningham, which he had shared with the owner.

That, officially, was Class 3, though to the crowd it was the race itself, while Class 2 saw the Bristol finish a deserved first after their Le Maus set-backs, the Loyer-Rinin Gordini having broken its gearbox, followed by the Picard-Pozzi Ferrari and the Clarke-Scott Russell Frazer-Nash, having run many hours without a filler cap on the tank and having to stop twice as many times as scheduled. In Class 1 the brothers Pierre and Robert Chancel kept their oddlooking, but effective, Panhard in front of their team-mates and third was a DB Panhard driven by Bayol and Hannenmuller.

Race

As if all the foregoing were not enough for one meeting, preparations now began for the 40th Grand Prix Of France and the Ferrari threat of not starting did not materialise, naturally—the FIA consequences being too great—but they delayed their arrival until the last possible moment and received a huge ovation from the crowd when they eventually lined up in front of the pits. The cars formed up on the grid, there being Ascari, Villoresi, Farina, Hawthorn and Rosier on four-cylinder Ferraris, Gonzalez, Fangio, Bonetto, Mathison and Graffenried on Maserati Sixes, Moss with his Cooper-Alta, Bira and Salvadori with fuel-injection Connanghts, Claes with his standard Connaught, Collins, Macklin and Cabantous with HWMs, Bayol and Chiron with Oscas, Wharton and Gerard with Cooper-Bristols, and right at the back, having not practised, were the four works Gordinis driven by Trintignant, Schell, Behra and Mieres.

While Faroux was preparing to drop the starting flag, amidst cries of derision from the crowd every time his name was mentioned, it was rather noticeable that Moss and Cabantous had only recently finished completing the 12-hour race, doing the last three hours of driving, and Chiron, Mieres and Behra had not practised on the Grand Prix cars. Violation of regulations seemed to be part of the Reims organisation! With a Maserati-Ferrari duel coming to boiling point trifling matters took a back seat, and as the whole field roared off in a glorious start everyone waited to see the cars appear out of the Garenne woods on the far horizon and hurtle down the hill to Illinois.

Gonzalez leads the field at the start

Motorsport Images

A long line of red cars appeared, bunched closely under braking and then came screaming past the pits in a glorious tumult of noise and dust that restored everyone’s sense of proportion. It was Gonzalez who was leading, from Ascari, Villoresi, Bonetto, Hawthorn, Farina, Marimon and the rest, with Bira leading the non-Italian cars. Round they came again and Bonetto spun at Thillois, letting the four works Ferraris into a line behind the flying Gonzalez, then came Fangio and Marimon, followed by Trintignant showing his usual superiority over the followers.

Gonzalez drew away relentlessly and Ascari, Villoresi and Hawthorn ran so close together that at times they were literally side by side, chopping and changing positions all the time. Farina was back a little with Fangio and Marimon at his heels, and Trintignant crouching down in the Gordini cockpit endeavouring to do his utmost to keep the tail of the Italian horde in sight.

A large gap soon appeared between him and Graffenried and Bonetto, and then another long gap saw Bira come by with the Connaught way ahead of the rest of the field. Lap by lap Gonzalez increased his lead until he had some 20 seconds in hand by the end of lap 22; the three Ferraris were still engaged in a furious battle amongst themselves, while Fangio began to get into his stride to shake off Marimon and start catching Farina.

This he did, and just before half-distance he got by and was soon amongst the Ascari-Villoresi-Hawthorn trio. In making this gain he naturally tended to draw Farina and Marimon along with him and when at 30 laps Gonzalez came in to refuel. Fangio, Hawthorn, Ascari, Farina, Marimon and Villoresi were in such a tight bunch that all or any of them could be leading at any moment. This was a really cracking pace and it was going to be a survival of the fittest, with no time for tactics. With half the race run the first seven cars were still going as if on the opening lap, while the rest of the field was straggling along behind.

Fangio brings his Maserati into the pits during an intense French Grand Prix

Motorsport Images

Trintignant had burst the Gordini, Schell and Mieres also, Moss was having clutch slip and Salvadori had lasted no time at all. The idea behind Gonzalez was now clear; he had started with a small amount of fuel hoping to make up sufficient lead in the first half of the race, but it did not quite work out that way and be restarted in the midst of the battling mass of Ferraris and Maseratis. Still it was anyone’s race and by lap 33 Hawthorn and Fangio began to share the lead between them rather consistently and after another half-dozen laps a gap began to appear between these two and the remainder, which was still a turmoil of Gonzalez, Ascari, Farina and Marimon, Villoresi having tired and dropped back.

The young English boy was driving all he knew and lap after lap he and Fangio appeared out of Thillois so close behind one another that it looked like one car, which then split into two as they approached the pits and disappeared under the bridge and round the full-throttle righthand curve, side by side. This itself was real motor racing, but there was more to come, for behind came Gonzalez and Asian i locked in an equally deadly struggle and going through the same motions.

Now another flaw in the organisation made itself apparent for the programme said the race was over 56 laps, while the store sheets handed to the Press said there were going to be 60 laps. To make matters worse there were two loudspeaker announcers, operating and one said 56 laps while the other said 60 laps. If it had been 100 laps it would have made no difference to the furious battles waging out on the Circuit.

The Ferraris do battle on the pit straight

Motorsport Images

Neither Maserati nor Ferrari would give in and finally someone must have tossed up and said the race was going on for 60 laps. By three-quarter distance Bonetto was lapped by the “open war,” as was Graffenried, though for a time these two had played the part of the “prelude to the storm”, for the scream of their Maserati exhausts was acting as a warning of the approaching fury. Fifty laps went by and still no quarter was given.

The Ferraris refused to let go of the Maseratis, making up on braking anything they might be losing on speed. Hawthorn losing a little on the climbing right-hand turn past Geux and making it up again on the following left-hander and the hairpin leading to Gurenne. It did not seem possible that this pace could go on, for it was telling on spectators so must have been absolute hell for the drivers, but continue it did and Hawthorn, in his green windjacket, continued to do battle with Fangio in his blue and yellow jersey.

At the end of lap 58 the absolute peak was reached, of this and possibly any race ever before, when Hawthorn and Fangio dead-heated across the finishing line, to be followed by Gonzalez and Ascari also in a dead-heat as they crossed the line. The passing of Farina and then Villoresi, on their own at over 140 mph came as quite a relief. As they started the last lap Hawthorn had a slight lead over Fangio, while Gonzalez and Ascari were still in a dead-heat.

Victorious Hawthorne is pushed back to the pits after his epic duel with Fangio

Motorsport Images

Everyone was on their toes, this was going to be the finest finish of all time, the English were inches off the ground, Hawthorn, leading at Garenne, was still leading down the bill to Thillois; not only was this the motor race of the age, but an English driver was leading. Round the Thillois hairpin for the last time, four cars in a tight builds, all of them red, all of them with oval-shaped air-entries, for the Maserati had removed their grilles before the Start. The tension was terrific, Faroux raised the chequered flag and ” whoosh”, a blur of cars passed, Hawthorn, Fangio, Gonzalez and Ascari, as quick as that.

The cheering reached fever pitch, the crowds surged onto the course and the “also-rans”, who had all driven hard and fast for over 2 hours, came in one by one. Following the first four came Farina, then Villoresi, Graffenried, Rosier, Mathison, who had been forced to stop and repair his oil-radiator when a stone from Ascari’s rear wheel punctured it, Behra limping along minus many cylinders. Gerard, his Cooper-Bristol sounding very healthy but lacking Italian speed, with Claes and Collins bringing up the tail.

The race had finished with an Englishman coming out on top. The fact that he was not driving an English car matters little; when the flag fell be started on equal terms with the great names in motor racing and was the first to receive the chequered flag. Not only had he kept the Union Jack high, but he had also put the ” Rampant Horse ” back on its hind legs after it had stumbled noticeably.

The Reims-Gueux Circuit is not a difficult one on which to drive in comparison with many, so that sheer finesse of driving skill was not vitally important, but endurance and judgment were needed and, as all the drivers started on the same footing as the circuit had never been raced on before, Hawthorn can feel justifiably proud at having beaten the world’s finest drivers. Let us hope that every Englishman is equally proud of his effort.

1953 French Grand Prix Race Results

1. Mike Hawthorn (Ferrari) 2:44:18.6

2. Juan Manuel Fangio (Maserati) + 1.0

3. Jose Froilan Gonzalez (Maserati) + 1.4

4. Alberto Ascari (Ferrari) + 4.6

5. Guiseppe Farina (Ferrari) + 1:07.6

6. Luigi Villoresi (Ferrari) + 1:15.9

7. Toulo de Graffenried (Maserati) + 2 laps

8. Louis Rosier (Ferrari) + 4 laps

9. Onofre Marimon (Maserati) + 5 laps

10. Jean Behra (Gordini) + 5 laps

11. Bob Gerard (Cooper) + 5 laps

12. Johnny Claes (Connaught) + 7 laps

13. Peter Collins (HWM) + 8 laps

14. Yves Giraud-Cabantous (HWM) + 10 laps

15. Louis Chiron (OSCA) + 17 laps

16. Felice Bonetto (Maserati) Retired – Engine

17. Stirling Moss (Cooper) Retired – Clutch

18. Prince Bira (Connaught) Retired – Differential

19. Elie Bayol (OSCA) Retired – Engine

20. Ken Wharton (Cooper) Retired – Wheel bearing

21. Maurice Trintignant (Gordini) Retired – Transmission

22. Lance Macklin (HWM) Retired – Clutch

23. Harry Schell (Gordini) Retired – Engine

24. Roberto Mieres (Gordini) Retired – Axle

25. Roy Salvadori (Connaught) Retired – Ignition

Championship Standings

1. Alberto Ascari – 28

2. Mike Hawthorn – 14

3. Luigi Villioresi – 13

4. Jose Froilan Gonzalez – 11

5. Bill Vukovich – 9