Later, we arrived at the first timing strip, reminiscent of Brooklands, and later still at the centre of the course where officials, timekeepers, and others of the cognoscenti were gathered. There was also a vigorous electrical generator, busy making the ” juice ” for the timing apparatus, a telephone installation, and a huge loud speaker which swung about and reported progress to the crowds up and down the course. Everything seemed to have been provided for, including a first-aid outfit discreetly hidden behind the official stands. Fortunately the latter was called out but once, when a three-wheeler shed a tyre, made a dive towards the roadside, and so scared a gendarme that he made a wild jump into a ditch, breaking his leg. Meanwhile I had toddled on to the parking point at the further end of the course, leaving the Major in company with George Brough—he of the cheery voice— to glean any good news during my absence. It was not an easy walk, those second two miles—did I say that the day was bright and hot?—but a pressman knows only duty, and there was compensation in seeing some of our own men, Le Vack, complete with green jersey, Temple and Judd, flash by on their attempts to win more world’s records for Britain.

A happy party were busy at the further end, Cyril Pullin and his brother; Vivian Prestwich, partially disguised in an Alpinist chapeau; and several others who are familiar figures at Brooklands, all hard at work helping our trio of speed cracks. An alfresco buffet reminded me that I had broken fast early that morning, but a loaf of bread, a flask of wine—but no “thou”—helped to fill the gap. A chat with one and another, a few snapshots, and it was time to start on the return tramp. On the way back I was passed by the big Fiat, Eldridge up, and marvelled at the lack of confidence in his steering abilities displayed by the onlookers who took cover behind tree trunks or in the ditch. But, then, they had not seen him pirouette around the brink of the Byfleet banking. Thomas—Rene, not Parry—on his 12-cylinder Delage, came by also. A sweet car this, finished in dappled aluminium, and streamlined in all except the tyres: what a ” bus” for a week-end run to Brighton ! Eldridge, I heard later, had done 147.03 m.p.h. as the mean speed of two runs in reverse directions over the kilometre, but as a reverse gear had been left out of the car’s make-up, the performance could not qualify as a record. Nevertheless, the speed actually was attained, and officially timed. Thomas’s speeds of 143.29 m.p.h. for the kilometre and 143.32 m.p.h. for the mile, were set down as records.

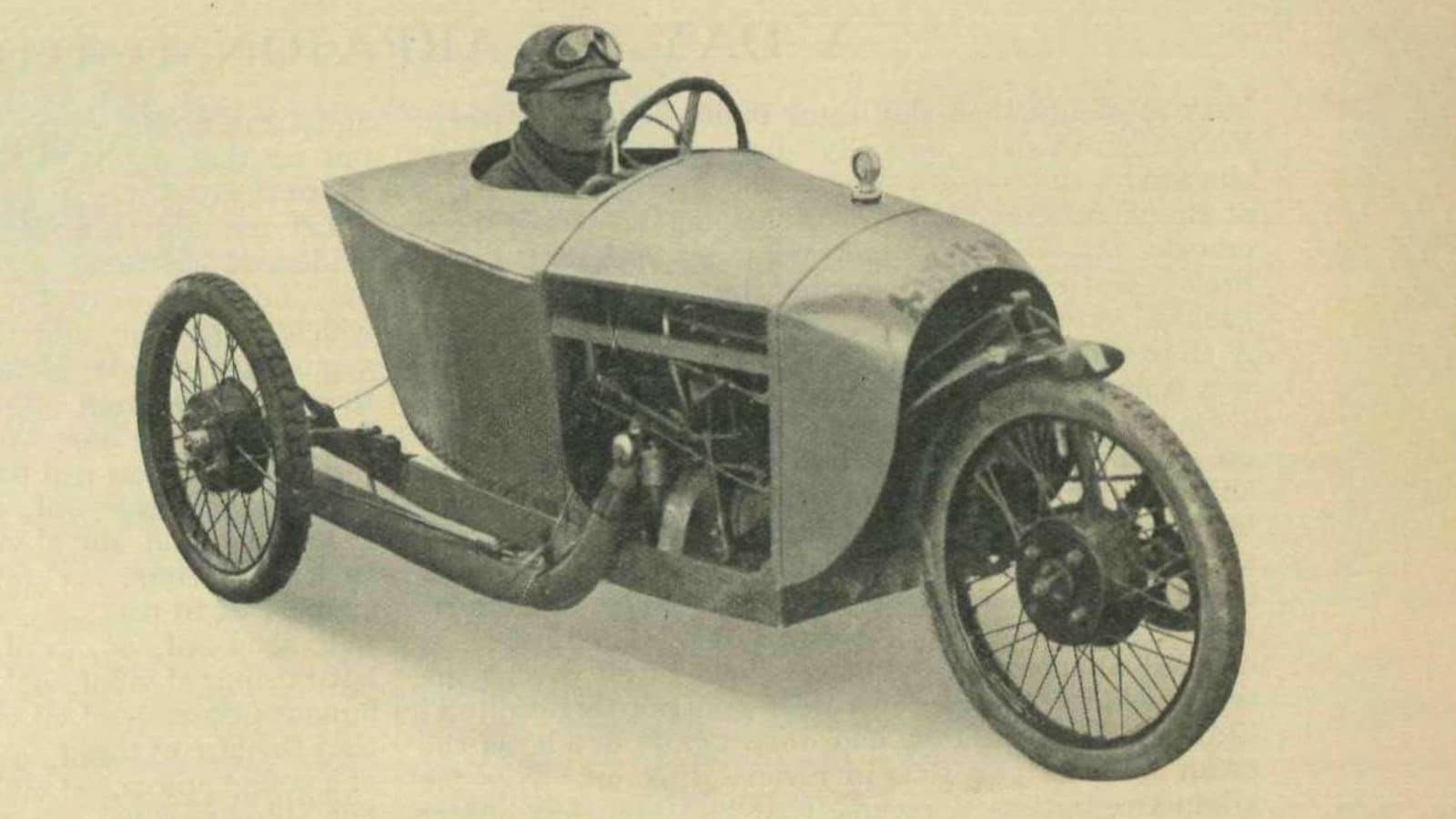

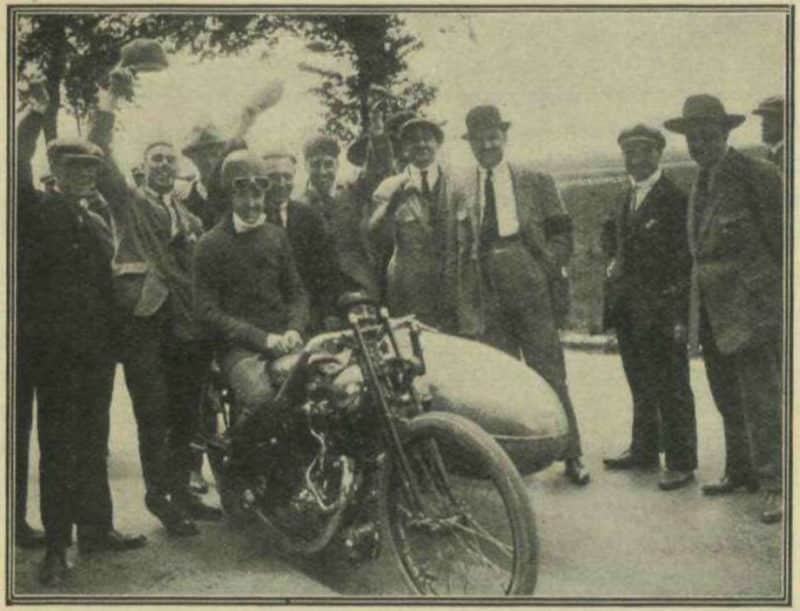

The 100 M.P.H. sidecar. Mr. H. Le Vack on his 1,000 c.c. Brough-Superior-J.A.P. Sidecar (passenger M. Cheret_ at the Arpajon Speed Trials, where he put up two world’s records at over 100 M.P.H. Riding solo he attained the speed of 123.08 M.P.H.

Dissatisfied with the peculiar position arising out of the above, Eldridge made arrangements for a reverse gear to be fitted to his car, and on the 12th July, over the same course, put up the following figures : kilometre, 146.86 m.p.h., and mile 145.57 m.p.h. [Subject to official acceptance by the I.F.A.C. they rank as records.—Ed.]. The motor cycles, too, had not been dawdling. Le Vack had put the sidecar record, for the first time, to over 1oo m.p.h. and, riding solo, had achieved the wonderful speed of 122.44 m.p.h. And the Frenchmen liked it. All along the course they waved hats and cheered the appearance of the green jersey, as our ‘Erb handed out the grand vitesse in the most approved fashion. Verily it was a wonderful show, and I rather fancy that a goodly few of the 34 records put up that day, by many types of automobiles, will adorn the record list for some little time to come.

Let me add that the arrangements for the meeting evidenced careful and thorough preparation, and the only criticism one could offer was that the meeting, which started at 9 a.m., dragged somewhat when, at 5 p.m. the standing start runs had yet to be carried through. Rejoining the Major, we started upon the two mile tramp to our taxi, pausing only to enjoy a wordy altercation between a farmer and a hobbledehoy cyclist caught riding over his flourishing crop of chicory. Of our reunion with our chauffeur—of our dash back to headquarters over pavé whereon our ample tyres enabled us to pass it through many “sports” cars less well shod—of our graceful acknowledgment of the hat-raisings of villagers, who clearly mistook us for more famous persons—and of our pleasant surprise on finding that the hire of the car was amply settled by a payment of a pound apiece, I will not tell at length. These were but sideshows to the big picture, the world’s record achievements. But, that credit may be accorded where due, I append a few figures of the British riders’ performances :—

| Kilometres | Miles | |||

| secs. | m.p.h. | secs. | m.p.h. | |

| Solo Motor Cycles, 250 c.c. H. Le Vack, New Imperial J.A.P. |

*25.17 | 89.09 | *40.34 | 89.25 |

| Solo Motor Cycles, 350 c.c. R. N. Judd, Douglas |

25.465 | 84.87 | 41.375 | 87.03 |

| Solo Motor Cycles, 1,000 c.c. H. Le Vack, Brough-Superior J.A.P. |

*18.79 | 119.05 | *30.27 | 119.3 |

| Sidecars, 350 c.c. R. N. Judd, Douglas |

30.115 | 74.35 | *49.265 | 73.102 |

| Sidecars, 1,000 c.c. H. Le Vack, Brough-Superior J.A.P. |

*22.145 | 99.8 | 36.095 | 99.735 |

All above are mean Speed times and Speeds; those marked * qualify as world’s records