10 legends that shaped F1

The Formula 1 world championship hits 75 this year. So who are the key influencers behind grand prix racing as we know it today? Damien Smith ranks the GP titans

Getty Images

Juan Manuel Fangio at Silverstone in 1956, on his way to his 19th F1 World Championship win – and his sole victory in the British Grand Prix

10. Fangio

Five-time world champion who set the benchmark for the professional F1 driver

“He was the greatest of them all,” said Stirling Moss. Who are we to argue? Especially with another who could also have made this list. When ‘The Boy’ joined ‘The Maestro’ at Mercedes for 1955, he had no fears about going up against the best. He craved the comparison, he wanted to know: what was it about the great man? “The art of driving a racing car is keeping it balanced,” said Moss decades later. “Acceleration, steering and braking are all inclined to unbalance a car but Fangio could somehow go closer to the edge of disaster than anyone else because of his feel.”

Moss found out firsthand over a season of one-team domination, and it was an experience that informed his outlook forever after. He deferentially and unquestioningly accepted his place as The Apprentice to the undisputed Master as the Mercedes ‘train’ swept around Europe. Moss was probably better in sports cars, but in Formula 1 (at this stage) he knew his place.

Fangio didn’t arrive in Europe until he was 38, having forged his skills in lethal South American long-distance races, and was the least established of Alfa Romeo’s ‘three Fs’, with Giuseppe Farina and Luigi Fagioli, in the opening season of the world championship. But while it was Farina who claimed that first title, Fangio rapidly emerged as the shining light of the immediate post-war generation. The career stats make that clear: five world titles in seven seasons; 24 wins from 51 starts, a ratio of 47% that’s never likely to be beaten. But much more than that, it was how Fangio presented himself, how he interacted with people, how he was that made him a class act.

And canny, too. From Alfa to Maserati to Mercedes to Ferrari and back to Maserati again, Fangio knew his own worth to always land in a competitive seat. Sure, how Peter Collins gave up his own title ambitions at Monza in 1956 to hand his car to the undisputed team leader was an astonishing act of sportsmanship – but one that Fangio didn’t blink in expecting or accepting. As Moss took note, Fangio was a true professional and ruthless when he had to be. This was his life, after all. It wasn’t a game.

It’s back to the drawing board for Adrian Newey, who now intends to sprinkle some title-winning stardust on Lawrence Stroll’s Aston Martin

9. Adrian Newey

Formula 1’s greatest, most successful designer. Now aiming to make Aston Martin a winner

Now here’s a man who has shaped Formula 1 in a literal sense, across a span of five decades. Adrian Newey’s shrink-wrapped Leyton House Marches of the late 1980s set F1 on its aerodynamically optimised course through the early years of the computer age.

Gloriously analogue in his drawing board methodology, Newey himself dismisses his artisan approach as nothing more than the medium for his ideas. It’s not how he does it, but what he does that counts. In reality, we’re left wondering whether he sees the world in ones and zeros, like a character in The Matrix. Can he actually visualise the molecules of air he so effectively manipulates to such astounding effect?

Independent in mind and spirit, Newey might never have left Williams had Frank and Patrick Head offered him a say in major decisions – such as sacking Damon Hill. He quit the team in the same year as Renault, but Newey was surely the greater loss. A single employee more influential than a major car manufacturer? In this case, yes.

Perhaps he’d have stayed at McLaren too if Zak Brown instead of Ron Dennis had been running the team in the 2000s. Mistakes were made at Woking under Newey’s watch as the Rory Byrne/Ross Brawn/Michael Schumacher axis gained the upper hand. But nobody’s perfect.

A breath of fresh air at Red Bull rejuvenated him – he says it was like a well-funded Leyton House – until last year that awkward schism opened up with Christian Horner amid serious questions about the team principal’s behaviour. Newey has consistently made the difference, which is why we’re so intrigued by what might happen next at Red Bull without him and where he’s going next.

A dozen constructors’ championship, 14 for the drivers lucky enough to land in his cars, across three teams – no one else comes close to that record. Now he’s fired up to do it all again as the key signing of Lawrence Stroll’s well-resourced Aston Martin superteam. Why is he pressing on? Because racing is his first love – and he just loves to win. No wonder there’s talk Max Verstappen might follow him.

What could possibly go wrong?

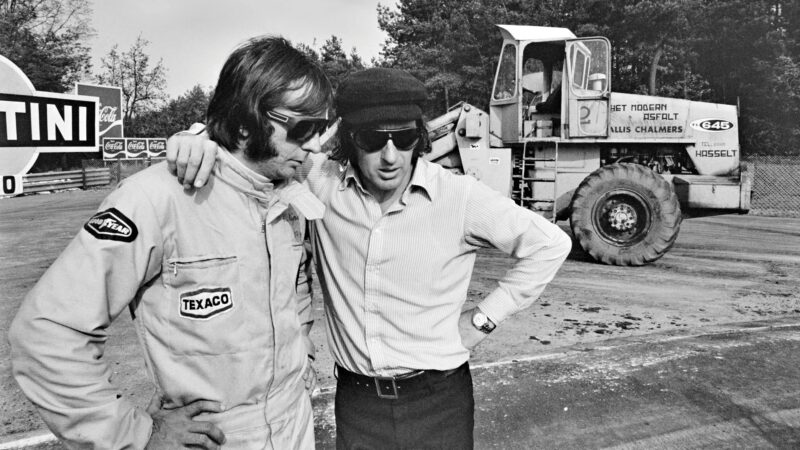

Emerson Fittipaldi and F1 safety campaigner Jackie Stewart inspect resurfacing work at Zolder in 1973 – just a week before the Belgian GP

8. Jackie Stewart

Fast and brave – in more ways than one. He refused to accept Formula 1 was a blood sport

Which Jackie Stewart are we talking about? The answer is all of them. First, he was the precocious newcomer who belonged immediately on the same piece of race track as his friend and countryman Jim Clark. How the pair might have matched up had Clark survived 1968 is among the great lost rivalries. Instead, he faced (and bested) Jochen Rindt, Emerson Fittipaldi, Ronnie Peterson, Chris Amon, François Cevert and more in a topline career that lasted eight years – the numbers left teetering on 27 wins from just 99 races.

Already a three-time champion, he missed out on the round 100th, devastated in grief at the cruel loss of his young team-mate, friend and protégé Cevert. This is what he’d been banging on about in the face of so much resistance and disgust – including, so infamously, from our own Denis Jenkinson. Denigrated by DSJ as a “beedy-eyed Scot”, such views on the drive to make motor racing safer haven’t weathered too well. Not for the last time, JYS would prove both aggravating and right.

Post-retirement, Stewart’s influence only expanded. He continued to bang the safety drum, while nurturing fruitful commercial relationships in an F1 world opening up to new possibilities. He was never ashamed to make money. Why should he be? Like his hero Juan Manuel Fangio before him, JYS has always known his own worth.

Eventually he’d see the sport from fresh perspectives: as a racing dad, as a team owner and ultimately a race-winning constructor. Having convinced Ford to bankroll his team, he then sold it back to them. Not bad for a “certified halfwit”, as FIA president Max Mosley contemptuously labelled him. They’d never got on ever since the March 701.

Stewart raised the bar, as a fast and naturally gifted racing driver, as a businessman and as an F1 man of rare principle. Now he’s fighting again, against his dear wife’s dementia. JYS never did know when to quit.

Shades of grey: Ron Dennis at the McLaren helm for the 2002 Brazilian GP

7. Ron Dennis

Inherited McLaren, then invented the modern Formula 1 team in his own fastidious image

A complex man, Ron Dennis wasn’t always easy to like when he was a fixture in Formula 1 paddocks. But behind the aloof air of superiority you could also sense a vulnerability. What ultimately made him easy to respect was his work ethic, the integrity and the (sometimes naive) idealism. A drive for perfection elevated Dennis beyond his peers as he created the template example of F1 excellence.

The beginnings as a mechanic at Brabham and Cooper are periods he doesn’t like to dwell upon, but they informed his ambition for autonomy. The Rondel Racing, Project Three and Project Four years in Formula 2 during the 1970s were tough, but gave him the knowledge he needed to pitch his vision to Marlboro. The alliance and eventual takeover of McLaren, in partnership with an equally complex but inspired John Barnard, was the floorplan upon which he could impose his reality and sculpt from all that he had learned.

Dennis empowered Barnard to create the first all carbon-fibre F1 chassis; he convinced Porsche to supply its potent turbo engine under the TAG moniker; he talked Niki Lauda into a return; re-signed Alain Prost, the best driver of the new generation. But more than all this, he created a business with infrastructure and methodologies that transcended its status as a mere racing team. From now on, F1 entities were elite pioneering specialists in new technology.

The 1980s heyday with Lauda, Prost and Ayrton Senna made McLaren unbeatable at times. A fresh alliance with Mercedes and new commercial relationships fuelled his vision for empire building.

The final F1 years – ‘Spygate’ churned by a vindictive governing body and a messy decoupling from McLaren – have clouded his legacy. But they shouldn’t. Ron Dennis left his mark on the whole sport. A forgotten man? Never by those who witnessed his impact.

More than a racing driver, Lewis Hamilton’s weight of character has made him a hero to millions

Ferrari

6. Lewis Hamilton

Transcends Formula 1 as a cultural sporting figure, a role-model to millions

Here’s something else Ron Dennis has to answer for. His instinct to listen and respond to the young lad who gamely approached him at an awards ceremony was another good call, perhaps his best one.

You know the story and the numbers: 105 wins, 104 pole positions, seven world championships – so far. No Formula 1 driver has been more successful. Yet somehow Lewis Hamilton remains divisive. We can’t think why.

The detractors say that for years he benefited from the best cars – just like every multiple world champion before him. They also scoff at his sense of fashion. Or his earnestness in interviews and on social media. For some, he can do no right.

But for millions of others, Hamilton is an icon and an inspiration. As the first and still only person of colour to achieve sustained success in F1, he speaks to a wider audience for whom grand prix racing meant little before he burst fully formed on to grids in 2007. They love the fact he’s upfront, honest, has no fear of expressing himself through the clothes he wears – and speaks with conviction for minorities and the disadvantaged. Only Sebastian Vettel has matched him as a racing driver with the confidence to address weighty subjects outside of their normal sporting sphere.

Hamilton’s F1 career has been so long he’s grown up in an uncomfortable spotlight. It was easy to pick holes during his tarnished final years at McLaren, but naturally he’s matured and the vast racing experience he accumulated has made him a complete sportsman. Yes, Mercedes gave him great cars, but he played his part in making them so and absolutely made the most of them. And for someone who has been around for so long, there have been remarkably few controversies. He has a reputation, unlike Ayrton Senna or Michael Schumacher, for racing clean. Even in 2021 when his rivalry with Max Verstappen spilled into dangerous territory, Hamilton emerged with integrity intact. He’s a great example to those who wish to follow in his wheel tracks.

Now the Ferrari adventure begins. Yes, money is a factor. It always is. But surely it’s the challenge and the adrenaline shot of what this means that he’s relishing. Whatever happens, his place as one of the greats is assured – and he remains what he has always been: box office gold. We’ll miss him when he’s gone.

The Prof, Sid Watkins, was pivotal to both improving race safety and modernising F1

Getty Images

5. Sid Watkins

Served on the frontline of saving Formula 1 lives to lead a gradual, vital revolution

If Jackie Stewart kick-started the conversation, Professor Sid Watkins was the man who put those words into action. For 26 years – some 424 races – he served as Formula 1’s doctor. For every driver through two decades and then some, Sid was a friend and the first welcome face on the scene when it all went wrong. When it wasn’t too bad, his prescription of whisky and a couple of aspirin usually did the trick.

By day ‘the Prof’, as he became universally known, was one of the world’s leading neurosurgeons working at the Royal London Hospital. Luckily he was in charge of the staff rota and kept grand prix weekends free – or used his holiday. Watkins became an F1 fixture and his eminence cannot be overplayed. Experiencing firsthand the woeful excuse for medical services at race circuits, the Prof became an increasing voice of influence as safety finally became the first non-negotiable principle of motor sport. It all seems so obvious now. Easy to forget that for decades medical care at race tracks was considered an expensive afterthought.

Watkins first served at Watkins Glen during the 1960s, when his work had taken him to New York. Upon returning to the UK, the British GP became his beat – before a pivotal meeting with Bernie Ecclestone in 1978. They didn’t know each other, but Ecclestone approached the Prof and recognised a kindred spirit. If F1 was to become a legitimate sport on a commercial level, it had to be safer. Sid, his opinions and his expertise became an essential ingredient to a sport that was finally maturing.

The Prof’s experience of treating Ronnie Peterson at Monza in 1978 galvanised and convinced him of his mission. Improvements in facilities, circuits and the cars themselves were – and still are – a work in progress. But so much we take for granted today began with one of F1’s most-loved figures, who on one hand didn’t take life too seriously – and yet on the other cherished its value and saved so many.

Colin Chapman, arms aloft after a Lotus 1-2 in the 1978 Spanish Grand Prix; Andretti and Peterson were driving Lotus 79s

Getty Images

4. Colin Chapman

Charismatic leader and innovator who shaped the so-called ‘golden era’

Can you imagine 1960s motor racing without Colin Chapman? The energy he brought to his growing Lotus empire shot through Formula 1 like lightning. BRM, Vanwall – for whom he contributed – and Cooper all got there first. But it was Chapman’s Lotus which really drove the narrative of the British F1 revolution.

Full monocoque chassis; engines as fully stressed members; the Cosworth DFV; four-wheel-drive experimentation; promising gas turbine racers; gaudy commercial sponsorship… Chapman found inspiration from wherever he could find it, never settled and never stopped, then passed it on. Adrian Newey was among the countless to be directly influenced, but practically everyone who followed carried something over from the Old Man’s example.

Through the 1970s, Lotus proved more inconsistent: brilliant one season, average the next. There were greater distractions to lead Chapman astray. But how he came back to what he did best, empowering Peter Wright, Tony Rudd, Martin Ogilvie, Ralph Bellamy and the rest at Team Lotus to push deeper into previously only lightly chartered waters, pulled him back to where he belonged. Harnessing ground effects was a team effort – but Chapman applied the pressure behind its game-changing suction. He was the charismatic leader good people need to achieve their best, but rarely also had enough know-how to lead directly by example.

He was flawed too, of course, made terrible mistakes and didn’t always show the best judgement – but that’s why he was fascinating. Chapman represented the best of F1, and then every now and then its follies too. But for all of the Lotus 25s, 49s, 72s, 78s and 79s, we wouldn’t want to be without the 76s, 80s and 88s. His loss from a heart attack at 54 was unquantifiable. No one could replace him.

So what on earth would he make of F1 today, with its prescriptive regulations and heavy limitations? We once asked that question to the ‘Marlboro man’ John Hogan, another big-hitting F1 influencer from an increasingly distant past. “Colin?” he replied. “He’d be in it right up to here. ‘Don’t worry, it’ll be all right!’”

Yellow helmet and the Marlboro-liveried McLaren is peak F1 of its era – here at the 1989 Italian GP

3. Ayrton Senna

F1’s single most inspirational figure – as much now as when he was racing

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” goes the old quote from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. So it is with Ayrton Senna.

His deification in the 30-plus years since the horrors of Imola 1994 has taken on the proportions of a cult. It’s a shame because the three-time world champion is becoming something of a cliché: “if you no longer go for a gap that exists, you are no longer a racing driver” – and all that jazz. In reality, the complete all-too-human picture of Senna, including the flaws, miscalculations and paranoia that existed within his natural charisma and sheer racing driver brilliance, is so much more interesting.

What is it about him? That documentary – 15 years old now, would you believe? – helps, of course. Then there’s YouTube, combined with the visceral era he raced in. We’ve all checked out the onboard clips of Senna at full pelt, with the frisson of ceaseless manual gearshifts and steering inputs on bumpy tracks with little or no run-off. It’s all just so raw in comparison to the calm and relative sanity of onboards today.

Then there’s the character. While Lewis Hamilton was inspired by him, Max Verstappen has probably more in common. They share a refusal to compromise, an attractive trait in heroes – even if in reality it can be a weakness as much as a strength. The nonconformist evokes an emotional response, certainly more than a clinical technician. That’s why Senna – the Jimi Hendrix of motor racing – is so high in this list and Alain Prost, his nemesis and equal, is nowhere to be seen.

Senna’s explosive speed and sheer intimidatory presence in that vivid yellow helmet represents the definition of what a racing driver is supposed to be, now to impressionable racers as much as then. Who else would inspire the string of tributes and celebrations we witnessed in 2024 during the 30th anniversary year? Like all who are taken far too young, Senna is frozen in his glorious zenith.

He’ll inspire for another 30 years yet, too.

Enzo Ferrari with the Scuderia’s rising star Phil Hill at the 1958 Italian GP – the American’s first Formula 1 podium

Getty Images

2. Enzo Ferrari

The myth-making titan of F1’s greatest team retains his old magic

It’ll be 27 years this summer. August 14, 1988. That’s when Enzo Ferrari left the building at the grand age of 90. Yet much like Ayrton Senna, the power of his legend somehow only intensifies the further we travel from his lifetime.

Ferrari’s aura is wrapped up in longevity. More than his blessed team’s unique status as ever-present from the start of the Formula 1 World Championship, it’s because the (original) Old Man’s history stretches back pre-war – even as far as immediately post-WWI – that carries weight. There’s old alchemy at work in the myth and gritty reality of Ferrari.

A racing driver in the 1920s, an, ahem, garagiste on behalf of Alfa Romeo in the 1930s, those opening decades forged the legend that was folded into his new endeavour as a constructor in his own right. Oh, and just how did he pick his way through that inconvenient Second World War? Another drop of mystery to the brew.

The Michael Mann film Ferrari, released late in 2023, tapped into the aura. Adam Driver didn’t look much like Enzo, but captured something of his spirit, and each scene was like a painting – a homage to Italy, where the soul of motor racing resides. And Ferrari is Italy.

Times have changed but the old Ferrari magic still lingers. See Lewis Hamilton pictured for the first time as a Scuderia driver, black coat draped over his shoulders, outside the old house at Fiorano, in front of an F40. Which other team could create such a frisson? When he made his first laps, the ghosts were everywhere. Ferrari has still got it – whatever it is. And it’s all because of the enigmatic man in the dark glasses.

Bernie Ecclestone, No1 – and, according to those who worked with him, a perfectionist. F1 owes him a great deal

Getty Images

1. Bernie Ecclestone

Creator of modern F1 as we know it – for worse, but mostly for better

What would Formula 1 look like today without the influence of ‘The Bolt’? The reality is F1 was too rough around the edges, too lawless to thrive in a fast-changing world back when Ecclestone was the boss of Brabham. It had to evolve. Bernie quickly identified the flaws once he had a place at the table after buying out Ron Tauranac in 1971, and recognised before anyone else just how much untapped potential existed in grand prix racing. Like the best racing drivers, he was faster, sharper and had a wider capacity to understand the bigger picture.

Money – that was always what it was about for Bernie. Even so, there’s a case to be made that his biggest contribution was on safety. It was Ecclestone who approached Sid Watkins and instigated significant change to reduce the death toll.

He’d seen the worst of F1 by the time he grabbed a stake in the game. Bernie knew F1, and from its early days. The loss of friends Stuart Lewis-Evans in 1958 and Jochen Rindt in 1970 informed his perspective on F1 as a blood sport. But this was no bleeding heart. John Watson’s account of how Bernie bluntly told him to get back in his car after the death of François Cevert shouldn’t be interpreted as callous. He was hardened to the reality that the show must go on. Death was bad for business, which is why he took an approach to at least try to eradicate it.

The power grab to snatch control away from race promoters and the governing body was ugly, but necessary. By the late 1990s F1 had been redrawn in Bernie’s own image. The alliance with old March chum Max Mosley at the FIA was key, but the pair misfired when they colluded to sell F1 to the highest bidder and allow it to fall into the hands of private equity asset strippers. By the end, Ecclestone – who had the foresight to trigger the original TV revolution and brought riches into the sport that left his rivals forever in his debt – looked out of touch, like an embarrassing uncle. By 2017 his time really was up.

But how it ended doesn’t take away how Bernie shaped every detail of F1 across 40 years. Yes, he took a great deal – but he contributed so much more.