Bentley Blower vs Speed Six: speed meets sophistication

Although the ‘Blower’ was about derring-do, it was the Speed Six that gave Bentley victories at Le Mans. Andrew Frankel takes to the track with two racing thoroughbreds which captured the spirit of the day

Jayson Fong

This is as much a tale of two people as two cars, and despite the images on these pages, neither of them is called Bentley. If two cars ever came to represent more accurately the characters of their creators, I know not what they are.

Both are famous but one is a legend. He is Sir Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin, a man who won the Le Mans 24 Hours just twice, and only once in a Bentley. The other man’s record at Le Mans – played three, won three – remains unapproached to this day. He was Woolf ‘Babe’ Barnato. Tim Birkin was not a heavyweight boxer, scratch golfer, powerboat racer or Surrey wicketkeeper and Barnato was all of the above and more. But then Barnato never wrote an autobiography, let alone one called Full Throttle dedicated to “all schoolboys”.

A Speed Six on the banking at the Brooklands Double Twelve – where, in 1929, ‘Tim’ Birkin and Woolf Barnato first met on track

Getty Images

Barnato may also have won Britain’s own version of Le Mans in a Bentley, the Brooklands Double Twelve, but he never smashed the outright lap record as did Birkin, the image of him in his at times literally flying single-seat Bentley, polka-dot scarf fluttering in hurricane-force winds, searing itself into the public imagination. And while Barnato died young at just 52 after surgery for cancer, it was not quite so tragically young as Birkin at 36, whose end was brought about from a wound received in a futile attempt to win the 1933 Tripoli Grand Prix because, unbeknown to Birkin, the result had already been rigged by some of the greatest drivers of the era.

Barnato was an elite high achiever who excelled at everything he tried. Birkin was a no guts, no glory merchant who at times gave the impression he’d rather go down all guns blazing than canter to an easy win. Barnato was more interested in ends than means, Birkin more in the race than its result. And if at the time you’d chosen to create two Bentleys that best reflected the outlooks of these spectacularly different personalities, you could not have done better than to come up with the supercharged Bentley 4½-litre ‘Blower’ and the Speed Six.

Birkin’s 4½ Litre ‘Blower’ was fast in the 1930 Le Mans 24 Hours but it didn’t go the full distance

Getty Images

These are the two cars that raced both against and with each other at Le Mans in 1930, the hands down finest hour in pre-war Bentley racing history. Birkin in his beloved ‘Number Two Team Car’ Blower, Barnato in his ‘Old Number One’ factory Speed Six. True to form, Birkin went fastest by far, but it was Barnato who went furthest. And won.

The irony is that without Barnato, Birkin would never have had his Blower. Famously, WO himself hated the idea, writing some decades later, his mood having clearly not ameliorated, “To supercharge a Bentley engine was to pervert its design and corrupt its performance,” and that it “went against all my engineering principles.” He died still believing it had brought his company’s name into disrepute and contributed to its downfall less than one year after its finest hour at Le Mans.

“Le Mans in 1930 was the hands down finest hour in pre-war Bentley racing history”

But by then he had long since lost control of the company that bore his name to Barnato and his “cronies” (WO’s words), so when Birkin, frustrated with the performance of the standard 4½ Litre, approached Barnato with a scheme for a team of four privately owned racing supercharged versions financed by wealthy Anglo-American heiress Dorothy Paget, which required the factory to produce no fewer than 50 road-going examples to homologate, he readily agreed.

WO, who at least remained in charge of the works racing team, took a very different approach, which was simply to optimise the big 6½ Litre, a car originally designed more for luxury travel than racing, for competition. The result was the Speed Six, heavier and less powerful than Birkin’s Blower, but somewhat more durable.

This continuation Blower at Silverstone is identical to the car that Birkin raced in 1930 at Le Mans; Andrew Frankel had also raced the car in 2023

Jayson Fong

The first time the two met on a track was at the Blower’s debut at the 1929 Brooklands 6 Hours in late June, and you’ll not be surprised by now to know that Birkin’s supercharged 4½ Litre went like a rocket and retired, while Barnato’s Speed Six cruised around and eventually won. Indeed the fact is that no Blower won any race in period, while Barnato’s Old Number One Speed Six won Le Mans twice all by itself, the first of just five chassis in history to have done so.

And so they meet again, in another time and another place. I know the Blower well for it is the continuation car I raced at the Le Mans Classic in 2023 and identical in every minutely identifiable regard to how Birkin’s car was when it raced at Le Mans in 1930. The Speed Six is less familiar, an original example recently acquired by Bentley for its historic collection. It is not in race spec but for the purposes of this comparison, it makes little difference.

It’s the Blower first. Memories of hammering down the Mulsanne in the dead of night, peering through an oil-smeared aero screen to the two faint pools of light ahead, trying to find a braking point at over 120mph will never leave me. In that moment I was Birkin. Today I can see everything and on Silverstone’s International Circuit we are as safe as can be. But what ‘Bentley Boy’ Jack Dunfee affectionately described as “that bloody thump” when the 4.4-litre fired up (it was never 4.5 litres, any more than the 6½ was 6.5 litres. Sharing the same bore, stroke, conrods and pistons, they were essentially the same engine, one with a couple more cylinders attached, albeit with a completely different way of driving the single overhead camshaft, four-valves per cylinder valve gear common to both) is the same.

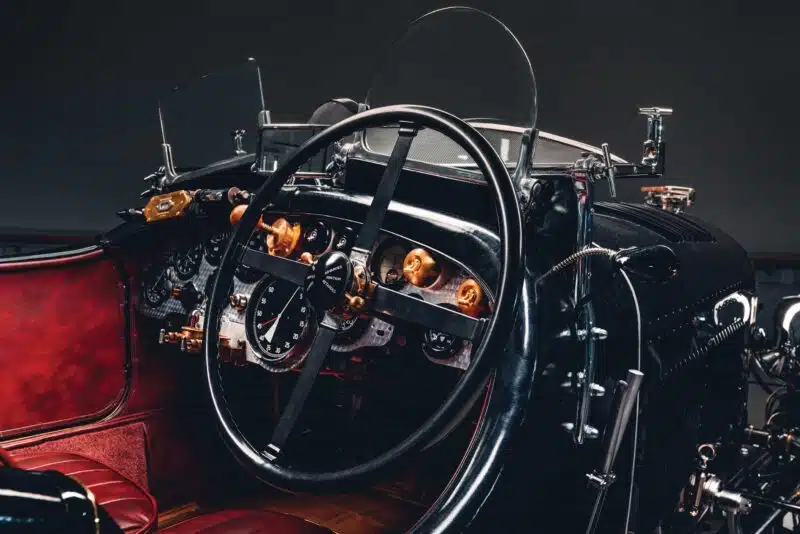

When driving the Blower, drivers need to remember that the accelerator is in the middle and the brake is on the right

The dashboard is a mad splat of dials of all sizes, but all you have to really watch are two glass bulbs in which pipes drip oil, each with a tap allowing you to adjust the flow. What you want is not a stream, but a drip, drip, drip. Anything less and the bearings within the supercharger will go dry and seize, with terminal consequences.

No need to remember the accelerator is in the middle and the brake on your right. For reasons I still don’t quite understand, my feet somehow already know and don’t need reminding. I’m far more likely to forget that the Speed Six has a conventional layout and tread on the wrong one in that.

“The engine is vibrating the whole car. You can’t really hear the supercharger but you can feel it”

In both cars the gearlever is by my right knee and the gearbox to which it is attached is the short-ratio ‘D’ box used for racing. The action is as you’d expect: long travel, oily fluidity, not a millimetre of slack. There’s no synchromesh but timing each shift is far easier than in Bentley’s more road-oriented boxes with their wider, longer ratios: there’s simply less time to wait between shifts because the engine has fewer revs to shed or acquire as you go respectively up and down the box, and therefore less time to make a mess of it. Get your double declutching right and the cross-gate second to third shift is literally as fast as you can move your hand. It’s probably the single-most delicious gearbox action I know.

Bentley’s Speed Six, leading, played a double act with the swifter Blower at Le Mans in 1930 to reel in Rudolf Caracciola’s Mercedes

Jayson Fong

We’re chuntering along now, the engine vibrating the whole car. You can’t really hear the supercharger but my goodness you can feel it. Some idea of its effect can be imagined when you learn that a standard street 4½ Litre Bentley engine develops 110bhp, while in a Birkin Blower the same engine made 240bhp.

There’s torque everywhere, but it definitely rises with engine speed all the way to peak revs (3500rpm normally, 3800rpm if you absolutely have to, 4000rpm in a once-in-a-blue-moon emergency). It’s all fairly predictable. What you don’t expect from a leviathan like this is for it to handle quite so well. Look at those spindly crossply tyres and positive front axle camber (done for reasons of steering load and high-speed stability) and you’d expect it to fall over at the first sign of a change of direction. Or just plough straight onto the grass. Not so. The drum brakes are extraordinarily good given how much work they have to do through so narrow a contact patch and can even be used to rotate the car on turn-in. And despite all the ironmongery out front – and quite unlike a road-going Blower – it doesn’t understeer at all. It requires a certain damn-the-torpedoes, chuck-it-in-and-sort-it-out approach but, my goodness, it works. I always wondered how on earth Birkin managed to beat all but one of a squadron of tiny supercharged Bugatti Types 35s to almost win the 1930 French Grand Prix until I drove his race Blower. Now I wonder no more.

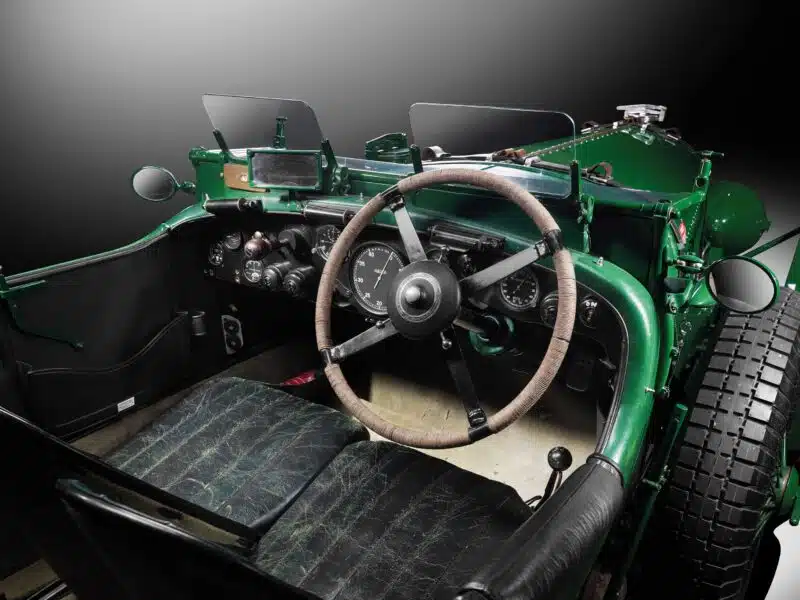

Built in 1929, this Speed Six has been part of Bentley’s Heritage Collection since 2021

The Speed Six seems and sounds so much more sophisticated you can scarcely believe their engines are so closely related. But as we have seen while supercharging more than doubled the output of the 4½ Litre engine, the best that Bentley’s engineers could do for the Speed Six was to up its output from 160bhp for the road to a round 200bhp for competition purposes. Installed in a heavier car with a longer wheelbase it never looked likely to keep up with the Blower.

The cockpit is far less Boys’ Own, the engine quieter and incomparably smoother. It’s voice is complex, more mellow and seems further away which, given the never-ending length of the bonnet, in very real terms it is. Remember the pedals and also that there’s more inertia in this engine thanks to its sheer size, so despite the same ratios, gearchanges will be slower. Instantly you are more relaxed, more at ease.

“The length of the wheelbase makes you adapt your style to something more Barnato, less Birkin”

It gets easier. Contrary to all expectations, the steering is actually lighter than that of its smaller sister. Though it clearly is not, the whole car feels somehow more modern. And the torque! It was always said of these cars that you could pull away at walking pace in top gear so I tried it, and you can. It pulls seemingly as hard at 1000rpm as it does at 3000rpm so you can be much more relaxed about how you go about making progress.

It’s clearly slower than the Blower, but not by as much as the difference in their respective power-to-weight ratios suggest. I think the bigger difference would likely manifest itself in the corners, where the additional mass and, in particular, length of the wheelbase makes you adapt your style to something more considered, less devil-may-care or, put another way, more Barnato and less Birkin.

But even today Le Mans is more about straights than corners and back then there were fewer than half the turns there are nearly a century later. And you could see how smart was the strategy deployed by the Bentley and Birkin teams to defeat the common threat of Rudolf Caracciola’s 7-litre supercharged SSK Mercedes: send Birkin out as the hare to push the Mercedes to breaking point, while Barnato and his other Speed Six-mounted team-mates kept watch from a distance, ready to mop up should their mutual rival fail. Which is precisely what happened. Birkin blew up, Barnato cleaned up. Job done.

The real advantage of the Speed Six over the 4½ Litre supercharged was its reliability – it finished races

Jayson Fong

I’ve always been struck by a stripped-down report on the same Speed Six after Barnato (ironically sharing with Birkin as his Blowers weren’t ready) after its first and his second win at Le Mans in 1929. Nothing could illustrate more clearly the incredible quality of the engineering that WO insisted upon for his cars, which Birkin chose to compromise for his Blowers. After 24 hours of racing, presumably around half of it conducted with Birkin’s no-prisoners approach to driving, the engine was dismantled and all its constituent parts measured for signs of wear and examined for signs of distress. Yet the ensuing report – written by Bentley’s famed workshop manager Nobby Clarke – reads in its entirety: “Nothing to report. Exhaust valves and valve springs replaced as a precautionary measure only.”

The Speed Six was excluded from its debut race because its dynamo drive had to be disconnected which was contrary to the rules. After that no factory Speed Six ever failed to finish a race through mechanical failure.

The Blower, more fun to drive though it is, had a less auspicious record. Perhaps the race that best illustrates the point was the Double Twelve 24-hour at Brooklands referred to earlier. Three Blowers and two Speed Sixes were entered. The Blowers all retired, the Speed Sixes came first and second. Says it all, really.

| Bentley 4½ litre Supercharged | Bentley Speed Six |

|---|---|

| Engine: 4398cc, four cylinders, with Amherst Villiers Mk IV Roots-type supercharger | Engine: 6597cc, six cylinders |

| Chassis: Semi-elliptic springs front and rear; Hartford friction dampers | Chassis: Semi-elliptic springs front and rear; Hartford friction dampers |

| Transmission: Four-speed D-type gearbox | Transmission: Four-speed, D-type gearbox |

| Power: 240bhp at 4200rpm | Power: 180bhp at 3500rpm |

| Max Speed: 125mph | Max Speed: 119mph |

| Weight: 1727kg | Weight: 2132kg |