The Motor Sport Interview: Derek Warwick

1992 Le Mans winner Derek Warwick on his humble stock car beginnings, working with Walkinshaw and why he’s giving something back

Getty Images

Derek Warwick did it the hard way. He starting in stock cars, winning the British title in 1971 and World Championship in 1973. Success followed in Formula Ford, Formula 3 and Formula 2, attracting the attention of the F1 paddock and a seat at Toleman for ’81.

Warwick raced for six F1 teams and for Jaguar and Peugeot in sports cars, winning Le Mans and the World Sportscar Championship in 1992. A former president of the BRDC, he is a regular steward at grands prix and runs the BRDC Young Driver of the Year programme, tasked with discovering drivers of the future. He lives in Jersey, where he is putting the finishing touches to a book about his life and from where he tells us about the highs and lows of a great career.

Getting noticed in Formula 3, 1978

Reinhard Klein

Motor Sport: It’s our centenary this year and you must remember our Denis Jenkinson and other Formula 1 writers. Were you always open with the media or were you wary of them?

DW: I remember Jenks from Motor Sport but not as well as the others like [Nigel] Roebuck, [Alan] Henry and [Maurice] Hamilton who followed my whole F1 career. I trusted them, told them things I didn’t want printed and they would respect that. It was mutual trust. On the other hand there were guys from The Sun newspaper, for example, who I wouldn’t tell anything. They always told me the misleading headlines weren’t written by them.

When you’ve been stung once you get more careful and you quickly learn who you can trust. I was always honest and I think that’s the best way with the media.

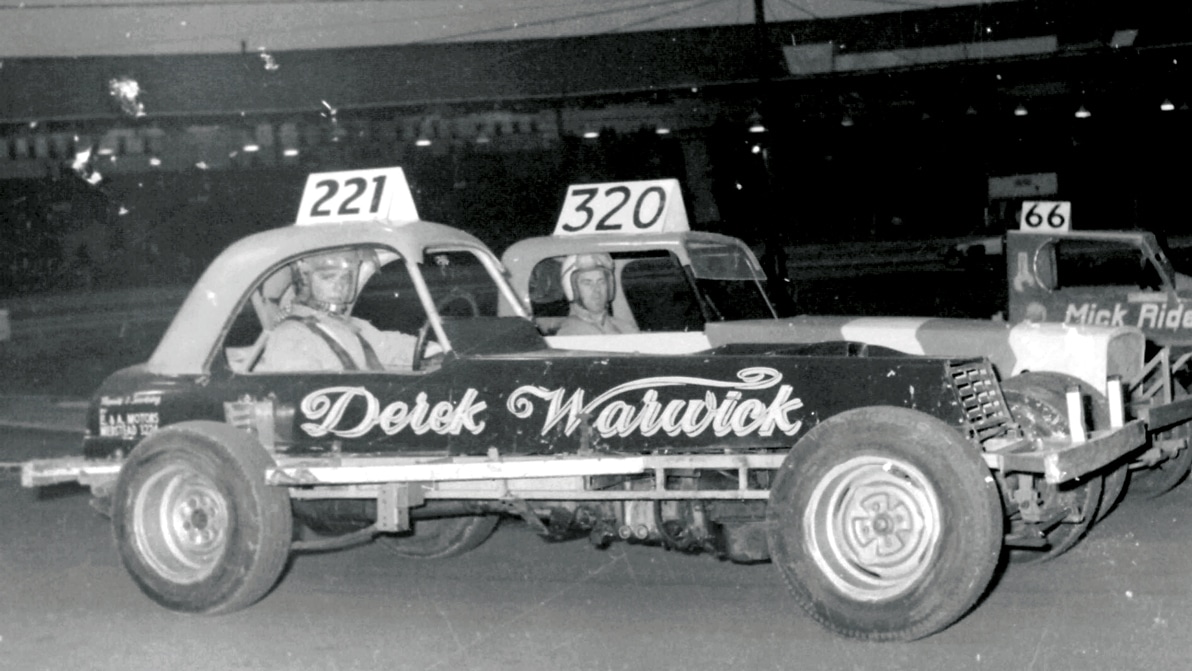

Where it all started out – stock cars, early 1970s.

MS: As a new kid on the block you ruffled some feathers in stock cars. Was that world a good grounding for the success that followed and what did you learn from that?

DW: My father and my Uncle Stan taught me early on how to deal with people who weren’t entirely straight. I sussed them out very quickly. What stock cars taught me was how to race. When we had 10 Formula Fords heading into the old Woodcote at Silverstone I knew where to place the car, how to make room for myself – that’s why I often came through in the lead. When there was an accident people would say, “That’s the stock car driver from Arlesford,” which was unfair but an easy punt for the sceptics. That all went away once I got into Formula 3, and later F1. Then people said how well I’d done coming from stock cars in Hampshire. That’s how it is.

MS: Would it be true that without the support of your father and your Uncle Stan you would never have risen through the ranks as fast as you did?

DW: Yes, one million per cent true. Without their help I wouldn’t have got as far as Formula Ford. Stan pushed me to the next level, into Formula Ford and F3, and they showed me the importance of being humble, being honest, being the person I am, there’s nothing to hide.

Mind you, they could be old rogues too and I joined in their parties a few times. The original Las Vegas race weekend comes to mind… but we’re not going to talk about that in print. Thanks to them my instincts about people are still pretty good to this day and they taught me a lot about life.

By 1980, Warwick had moved to Toleman – the team to beat in the European Formula 2 championship. He’d end the season second behind team-mate Brian Henton

Reinhard Klein / Colin McMaster 2024

MS: Then of course there’s Toleman, your first seat in Formula 1, with some financial support from Les Thacker at BP.

DW: I was lucky to find Les when I was doing Formula 3 in 1978. His funding got me through my last season there in ’79 when we were getting stuck for money. I thought my career was over and then I got called to BP House in London in December 1979, thinking there was no more money for me, but sitting there with Les were Roger Silman, Ted Toleman, Rory Byrne, Alex Hawkridge and Stephen South and I was told I was now to be part of an all-British team with Toleman sponsored by BP. So he saved my career. He was everything to me climbing the ladder.

The brilliant 1984 Renault but it rarely lasted the distance

Grand Prix Photo

MS: Back then Rory Byrne was still learning some of the skills for which he has become so highly respected. What was it that impressed you in those early days?

DW: He gave 100% all the time, and you can’t knock that. The concept of the first Formula 1 car, known by some as the Belgrano or the Flying Pig, was wrong – but he learnt from that. The ’83 car was so much better and that evolved into the ’84 car which Ayrton Senna raced and I went to Renault. The rest is history and Rory is still working in Formula 1 now.

Rory is a very clever guy, and his commitment to the job was always so impressive. After a race he’d be on the verge of collapse. We’d go to a bar on Sunday night and he’d be asleep at the table, and we’d be putting things in his hair, cutting bits off his jacket. He was honest too, and I was always honest with him, that’s why I stayed at Toleman for ’82 and ’83. If I made a mistake I’d tell him straight, I’d left two tenths out there. People don’t like liars and I never lied about what the car was doing or how I had been driving it.

A replacement for Elio de Angelis at Brabham, 1986

Grand Prix Photo

MS: We all remember the British Grand Prix in 1982 at Brands Hatch when the Toleman suddenly ‘came to life’. You were running it very low on fuel, weren’t you?

DW: Well, yeah, of course we were, we were desperate, we’d almost lost our sponsor Candy, so we needed a result.

“We ran the car on half-tanks and soft tyres and it just flew”

We decided to run the car on half-tanks and soft tyres and it just flew. When I passed Pironi at Paddock Bend I thought, “Maybe they have put fuel in this car… this is the way the car is – we can win this race.” I was up into second place when a half shaft broke but that day put me on the map and put the team on the map. I reckon it might have given Gordon Murray the clever idea of refuelling. I’ve never asked him but only a few races after that the Brabham team started refuelling. We had to do what we did, we were running out of money and needed to keep the sponsors happy.

Monaco GP 1988 with Arrows

Grand Prix Photo

MS: Joining Renault in 1984 looked like a turning point in your career. The car was potentially a winner, but it was a bitter disappointment. What went wrong for Renault?

“Renault didn’t have the systems to repair all the breakages”

DW: In those days there were so many retirements. In half of all the races in my career I didn’t finish, and most of those were due to reliability. The turbo cars had enormous horsepower, but things kept breaking… gearboxes, differentials, turbos, intercoolers, and Renault just didn’t have the systems in place to repair all the breakages.

In ’84 the car was absolutely brilliant. We should have won at least six races. I re-signed for ’85 because Gérard Larrousse offered me a fortune to stay – then he just walked away. He left the team taking all our top engine and chassis engineers. So we lost the best brains in the Renault team. When I got in the car for the first race in Rio it was three and a half seconds slower than the ’84 car. The team had already lost heart because the season before I joined, with Prost and Cheever, was a disaster. Prost got some bad press and that’s how Patrick Tambay and I got the gig for ’84.

The team was too big. We had all the personnel, all the money, all the kit – but we didn’t have a British engineer with real racing pedigree who would have stabilised the team. We did a lot of development, we had great tyres from Michelin, but the car kept breaking down and the chassis was flexing. We lost momentum. Renault had brought in people from the road car manufacturing side and they knew absolutely nothing about Formula 1. We still had a good engine and we saw that with Lotus when Senna started winning races with it.

Warwick spent 1990 with Lotus, driving the Lamborghini V12-powered 102 but just three points were earnt

DPPI

MS: How did you deal with Senna blocking the drive you thought was yours alongside him at Lotus? It must have been a huge setback?

DW: I went to Lotus in December for them to sign their side of the contract and it was effectively torn up in front of me. I was devastated, completely lost, I had nowhere else to go. I needed to get myself back out there so I went to Daytona and raced a Porsche 956, and that attracted the attention of Jaguar so I ended up signing for Tom Walkinshaw. I loved those sports cars and they were good to me. I always had one of the best cars and winning was easy. I almost won the World Sportscar Championship three times – in ’86 the Jaguar V12 went down to 10 cylinders, losing me points. I was disqualified at Silverstone in ’91, and then finally won it in 1992, the year I won Le Mans with Peugeot. So, despite losing the Lotus drive, I never looked back. I should have signed for Williams in ’85, not Renault, but I never wished I was Nigel Mansell winning races, and hindsight is a wonderful thing.

When I saw the Lotus in ’86 I thought, “That could have been me.” But it wasn’t, that’s the big difference. It’s important not to look back, wish this or that hadn’t happened. When I’m working with young drivers now I tell them to make the very best of what they’ve got. Don’t wish you had a better car, a better team, just get your head down, focus, be fast, consistently beat your team-mate, and people will notice you.

Mark Blundell, Yannick Dalmas and Warwick will need a bigger trophy cabinet

DPPI

MS: When Elio de Angelis was killed in testing in 1986 you replaced him at Brabham – that was a traumatic experience for any racing driver, especially a friend.

DW: Yes, of course. I learnt within an hour that he’d been killed at Paul Ricard. I decided not to call Bernie Ecclestone out of respect for Elio even though I might lose the chance of that drive. After 10 days Bernie called me, said he completely understood and respected why I hadn’t been in touch but he wanted me to go and see him. He sent a plane for me, and it was difficult at first because all the guys at Brabham loved Elio, one of the nicest guys in Formula 1. And yet… I wanted to get back into the sport, none of the races clashed with the World Sportscar Championship, and Brabham was my only option. I knew the car wasn’t the best but the engine was amazing and Gordon Murray was there. He had always been able to transform a car with another clever widget, another brilliant idea. So I didn’t worry about how bad the car was, rather I focused on how good the car was going to be.

It was such a pretty, low-line car, but the engine was installed at a slant to keep the very low line and the aerodynamics and we had problems with the gearbox, the differential, the engine oil pressure and chassis flexing. I tell you, Bernie is as honest as the day is long. It’s difficult to agree terms with him but once you get there he is very honourable.

I had decided, in my head, I was worth £100m so I told him I didn’t want to talk money or contracts, I wanted to go and meet Gordon, the engineers and the mechanics, great guys like Charlie Whiting and Herbie Blash. Bernie said, “No, you sign the contract before you go through any of those doors.” He looked at me and said, “You may think you know what you’re worth – but this is what I’m telling you you’re getting,” and that’s what I got.

He still owes me a big one because he pulled me out of the car in Austria when Patrese’s engine blew up. I’ve never forgiven him for that. He’s a man of his word, difficult and hard, but fair and very clever.

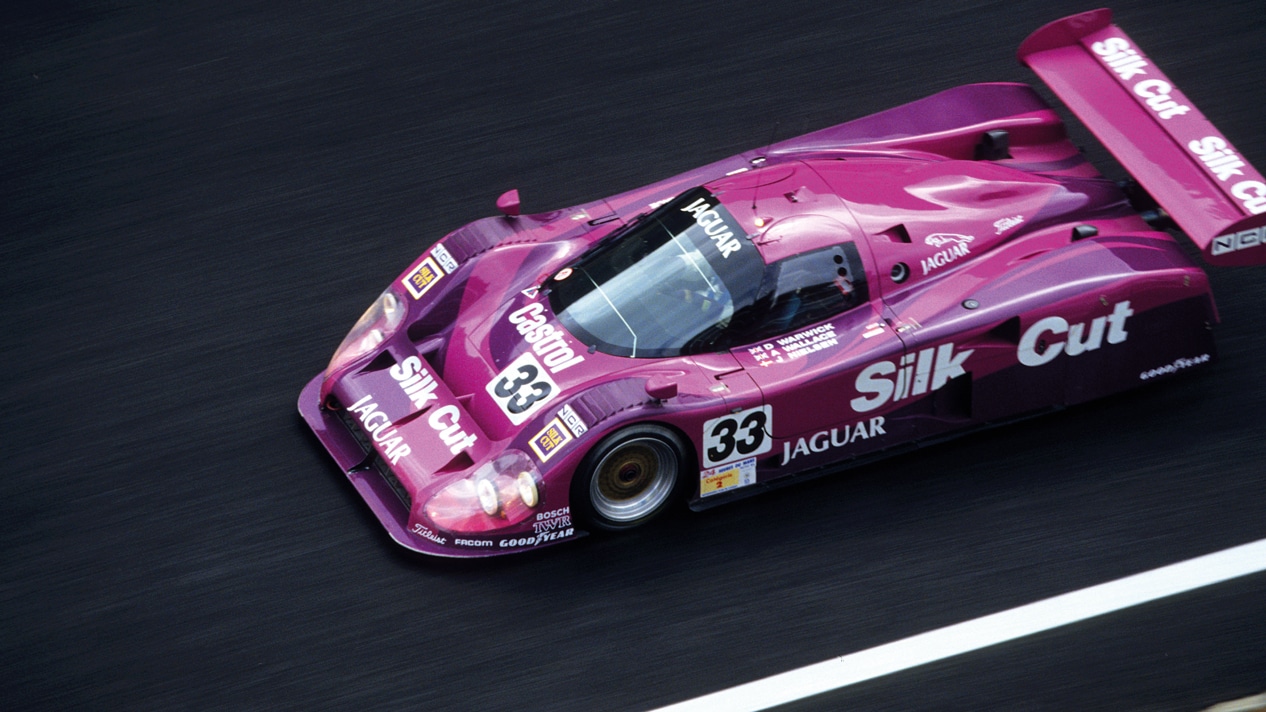

Leading a Peugeot 1-3 at Le Mans, 1992

DPPI

MS: You raced for both Ecclestone and Walkinshaw, two of the sport’s toughest operators. Were they similar to work for?

DW: Tom was very much in the mould of Bernie, not as clever, not as smart, and probably more devious because he got up to a few tricks. We didn’t have anything illegal at Jaguar in sports cars but in touring cars there were allegations of the rollcage being used to carry extra fuel, stuff like that.

He was a difficult man to please, a hard taskmaster, and he’d been a quick driver himself. For some reason we clashed. He was a massive fan of Martin Brundle and so I was always second best when he couldn’t get Martin. There was this ill feeling between us but he was clever. He always built winning cars, he always got the right people around him – like Ross Brawn with the Jaguar XJR-14 for 1991. It was one of the very best sports cars ever.

Tom ruled with an iron fist but you wanted to drive for him because he produced winning cars. I think he resented me in ’91 because he tried to get Martin to drive the car but he wasn’t available. Then Ross [Brawn] called me and told me he was about to build the most amazing sports car and said he already knew that Jaguar and Walkinshaw must have me in there. So when I went there I felt strong and came out with a phenomenal contract. I reckon Tom bore that grudge for the rest of my career.

Warwick’s third outing at the Le Mans 24 Hours was in a Jaguar XJR-12 in 1991 but he missed out on the podium – fourth in a Jaguar 2-3-4

DPPI

MS: What was it that made that XJR-14 such a special car?

DW: Ross Brawn. He was just the best, a concept man, and he understood what was needed. He got the right people to make it all happen, focus on the components of the car whether it be suspension, aerodynamics or whatever. Look at what he did for Ferrari, a typical Italian team that was all going off in different directions, and he steered them in one direction with Michael Schumacher.

The XJR-14 had a lot of downforce, it was nimble, light, a great racing car. When we first tested at Silverstone, I did an installation lap, came in, they opened the door and asked me how it was. I told them the car was simply amazing. When I went back out for some timed laps I will never forget the fast left hander that went past the makeshift pits into a chicane. I knew it was flat, and I came through there in sixth and Ross told me it looked so quick that they all ducked behind the barrier. They thought the throttle had stuck open… so we knew the car was going to be something special.

Jaguar XJR-6 , 1986 WSC

DPPI

MS: What do you see as your greatest victory – maybe Le Mans ’92, the World Sportscar title?

DW: To be honest, winning the Superstox World Championship in 1973 was something I really wanted and was totally focused on getting. It was the biggest thing in my world at the time and I wanted it, not just for me, but for my dad and Uncle Stan.

Then there’s getting my first Formula 1 drive, going to the grid at Imola that first day. I’d been a welder at Warwick Trailers, working 12 hours a day, and now I was a grand prix driver. It was a magic moment. But yeah, winning Le Mans with Peugeot, with Yannick Dalmas and Mark Blundell, and then the championship, that’s right up there. It was a year after the tragedy of my brother Paul being killed in F3000 at Oulton Park, and I wanted to pin that victory on Paul’s chest. Jean Todt knew this, and he knew how hard I’d worked on the development of the Peugeot, testing five or six hours at a time at night when the other drivers had gone away to sleep. We’d effectively won Le Mans with half an hour to go, Yannick was driving, a Frenchman in a French car, in France, but… Jean brought him in, took him out of the car, put me in to finish the race. He felt he owed me something and that’s what made that victory so very special.

Late ’90s touring cars… not a good time

Getty Images

MS: After 10 years in Formula 1 you went touring car racing, latterly with your own Triple Eight team running the works Vauxhalls. In hindsight do you think you underestimated the challenge?

DW: We were up against the cream of the crop, drivers like Rickard Rydell, John Cleland, Alain Menu, Jason Plato, Tim Harvey and you don’t underestimate those guys. Having said that I did have some big financial issues. I had five garages, I was working crazy hours, flying back and forth from Jersey to Southampton. Then, on a Friday night I’d be driving up to Croft or Oulton – and expect to be a racing driver for the weekend. I was competitive with Cleland but we were building a team so I stepped back and started running it with Ian Harrison and it wasn’t a good time for me. I thought I needed to carry on racing and I regretted it. How people can enjoy driving 300bhp with front-wheel drive boggles me.

MS: Let’s move on to your work with the BRDC Young Driver programme, something that’s very important for you. What do you get out of putting so much into this?

“We’ll see a woman in Formula 1 in the next five to ten years“

DW: Enormous satisfaction, putting something back into the sport. When Paul died in ’91 I joined the MSA Safety Committee. I’ve been there ever since, and I was on the FIA Single-Seater Commission, I’m an FIA driver steward – all these are giving something back. I was president of the BRDC and out of that came the SuperStars programme and the BRDC Young Driver of the Year. Parents call me, saying their son should be on the programme. I talk to teams through my connections as an FIA steward – I can advise these youngsters. I don’t think Lando Norris or George Russell, for example, would be on the grid without the support of these programmes.

We’ve had some amazing drivers and you know from the first lap they get into an F2 car that here’s somebody special. I love giving these young guys a chance to drive these cars and we have good judges like Dario Franchitti, Johnny Herbert, Darren Turner, so only the best will win the awards. It’s not just about driving – they do simulator work, fitness and media training.

People want to know when a woman will get into Formula 1 and I reckon we’ll see that within the next five to 10 years. The problem is the pool is so small compared to the boys. Very few girls want to start karting at five years old. Boys are more boisterous, they start earlier, so you’re gonna find a superstar from a much larger pool. Now we have the F1 Academy we’ll see more women coming forward, the quality will improve. Formula 1 needs a female driver.

Warwick – never looking back.

DPPI

MS: Tell us about your new book Never Look Back, which is published in June. Why now?

DW: It’s something I wanted to do for my family, my daughters, my grandsons. I want them to know the story of how lucky the Warwick family has been, to have done all the things we did, starting out from our trailer factory in Hampshire, a journey that took us from stock cars to a world championship. It’s definitely not a list of my results – it’s some history for the family, the tales of what we got up to over the years and I hope some of it is funny.