Hamilton: ‘What I’d really like to do, one day, is to drive for Ferrari’

When Matt Bishop heard the news of Lewis Hamilton’s big move, it came as no surprise... It was the plan all along

Getty Images

Although Mercedes has won only one grand prix in the past two seasons, it notched up 111 GP victories in the previous eight: a total of 112 over the past 10 Formula 1 campaigns, which constitute the entirety of the hybrid turbo V6 power unit era so far. In the same 10-year period Red Bull has won 66 times, Ferrari 22.

A veteran of 17 F1 seasons and 332 GPs, of which he has won an extraordinary 103, Lewis Hamilton may be occasionally bolshy, but that is merely a result of the pernicious melancholy he feels when his feverish ambition is not sated with the level of success to which he has become accustomed. What he is not is fickle. So although his team’s comparatively poor pickings over the past two years disappointed him, no doubt, that setback was by no means the sole genesis of his decision to surrender his contractual option to stay on beyond 2024.

On the contrary, he is a deep thinker when it comes to long-term planning, and for many years he has privately harboured a keen desire to race for Ferrari. I worked closely with him at McLaren during the five seasons that spanned my arrival in early 2008 and his departure in late 2012. During those years he did not mention to me his longing to race in rosso corsa; but then at that time ‘Ferrari’ was a dirty word in the corridors of power at the McLaren Technology Centre, so he would not have thought it prudent to do so, even though he was not unwilling to tut about a few of the team’s most senior directors if ever their superciliousness vexed him.

As the Formula 1 world titles arrived for Lewis Hamilton, the car collection grew (as did the holes in his jeans)

2015

Hamilton earned his No1 in karting

DPPI

Three years later, when I bumped into him on the Monday immediately after the 2015 Japanese Grand Prix, at Lex Tokyo Lounge Bar, in the Roppongi district of the country’s capital, he and I chatted for a short while much more openly, in spite of or perhaps because of the fact that he was in his third year at Mercedes and I was still a McLaren man. As soon as I returned to my hotel room, I jotted down what he had told me. I have all my old notebooks, which is how I can reveal that he said, among other things, “Sometimes you just feel you’ve been somewhere too long and need a change”; “What I’d really like to do, one day, is drive for Ferrari”; and, “That would be a great way to end my F1 career, wouldn’t it? To win championships for McLaren, Mercedes and Ferrari.”

He elaborated no further, and we went our separate ways. So what follows is my interpretation of recent events, albeit from a reasonably educated vantage point, since I knew him well when we were colleagues, I have the odd email and WhatsApp exchange with him still, and, long after he and I were no longer members of the same team, I continued to watch his magnificent career very closely and with great interest, undiminished affection, and increasing admiration.

He arrived as a member of the McLaren Driver Development Programme (MDDP) in 1998, when he was just 13. No MDDP member has been remotely as successful as he has – although Lando Norris, Alex Albon, Kevin Magnussen, Stoffel Vandoorne and Nyck de Vries have each won races in many series and have all reached Formula 1 – and, as Ron Dennis and Martin Whitmarsh required of all their drivers, he remained short-haired and clean-cut until his departure 14 years later. Take a look at photographs of the McLaren super-launch in Valencia in 2007, his debut season in F1, and the aspects of his and Fernando Alonso’s looks that jump out at you 17 years later are their Full Metal Jacket, military-like crew cuts and silky-smooth chins.

Now, of course, Hamilton’s carefully curated dreadlocks, cornrows and stubble have become the world’s most famous follicular emblems of motorised speed, eclipsing in celebrity even Nigel Mansell’s trademark ’tache. They also reveal a greater truth about him. He never wanted to conform.

Hamilton and Fernando Alonso, McLaren’s Action Man line-up, 2007

Getty Images

Jenson Button, Matt Bishop and Hamilton, 2012.

Getty Images

“As he grew older he began to indulge himself with less reserve”

One of the reasons why he left Woking for Brackley was that he had grown weary of the conventionality and conservatism of the middle-aged white Anglo-Saxon males who ran the good but strict ship McLaren. After he had jumped that ship, and as he grew older, richer and more confident, he began to indulge and express himself with less reserve. He replaced his previous ‘man at Hugo Boss’ wardrobe with outlandish catwalk finery that better suited his newly modish hairdo. In addition to the assortment of McLarens and AMG Mercs that he had accumulated over the years, he added expensive classics and moderns made by companies other than those affiliated to the brands he was paid to promote, including a 1967 AC Shelby Cobra 427, a Ford Mustang Shelby GT500 of the same vintage, a Pagani Zonda 760 LH (the suffix letters indicating a one-off bespoke spec delineated by the man himself), and, yes, various Ferraris, including a LaFerrari, a LaFerrari Aperta, and a 599 SA Aperta. He began to collect A-list friends and acquaintances, too: Justin Bieber, Kanye West, Pharrell Williams, Will Smith, Robert de Niro, Brad Pitt, Jared Leto, David Beckham, Tom Brady, Neymar Jr, Rihanna, Shakira, Nicki Minaj, Kim Kardashian, Barbara Palvin, Sofia Richie, and of course Nicole Scherzinger, with whom he was in a passionate if occasionally tempestuous relationship for many years.

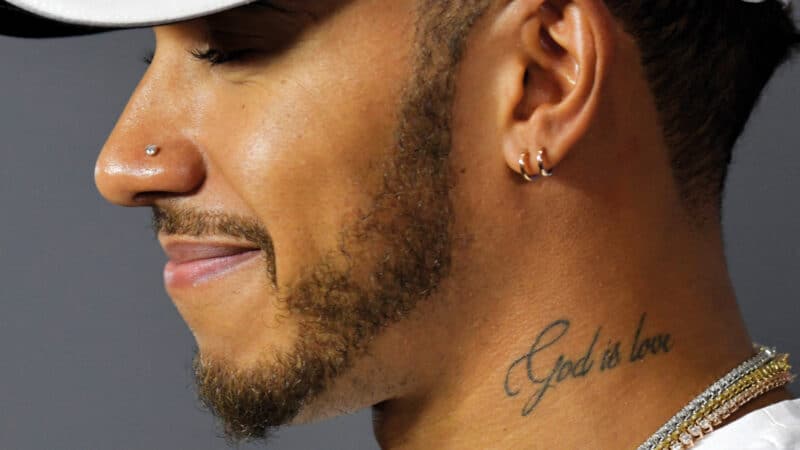

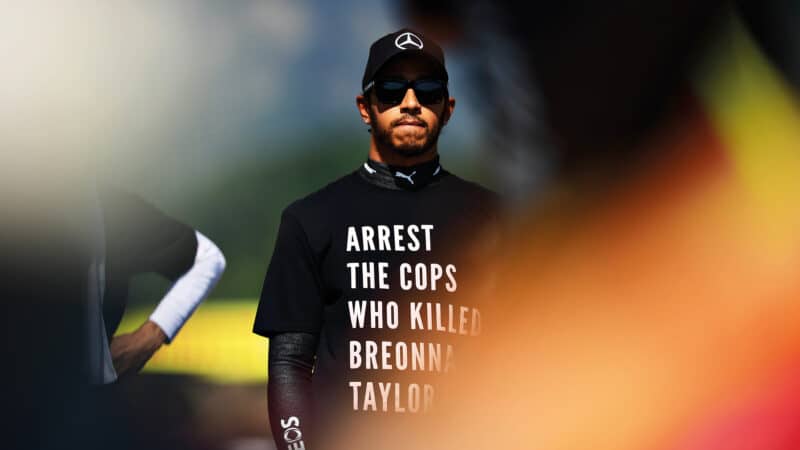

But what he found at Brackley was more middle-aged Anglo-Saxon males, no less conventional or conservative than those he had left behind him at Woking. Despite that, his interests and enthusiasms continued to diverge from the conservative and the conventional. He embraced Black Lives Matter (BLM), and he wore BLM-associated T-shirts during ‘take the knee’ moments before GPs, incurring the wrath of the FIA when he did so on the podium at Mugello in 2020, just as earlier that year he had also raised high-ranking eyebrows by clenching his fist in a black power salute on the podium at the Red Bull Ring. He wore flamboyant bling in the paddock, and he refused to remove his piercings in the cockpit, which conduct the governing body also sought to censure. His helmets began to sport LGBTQ+-supportive rainbow motifs, especially in countries whose anti-gay laws were and still are draconian and cruel. He spoke out trenchantly about all of the above.

Tats entertainment

Getty Images

Hamilton will spend a 12th season with Mercedes before packing for Italy – and a shot at an eighth world title

Mercedes

At Ferrari he will also encounter middle-aged white males. But – crucially in my view – very few of them will be Anglo-Saxon. Most Brits regard Italy as an exotic land and Italians as an exotic people – indeed the word comes from the Latin exoticus. The English-language surname that most closely approximates in meaning to the Italian surname Ferrari is Smith; yet, to us Brits, Ferrari is inordinately more glamorous. Equally, instead of the Dennises, Whitmarshes, Neales, Lowes, Wolffs, Allisons and Elliotts with whom he has been rubbing shoulders at McLaren and Mercedes these past 17 years, next year he will be working with men named Vasseur, Ioverno, Cardile, Gualtieri, Montecchi, Racca, et al: it will be a breath of fresh air for him. Moreover, his transfer from McLaren to Mercedes 12 years ago was engineered in the main by other people, including Simon Fuller, his pop-impresario manager at the time. By contrast, and importantly, his move to Ferrari is his own thing.

Among F1 drivers his hero is Ayrton Senna, who raced for four British F1 teams and was prevented by a tragic accident from ending his career at Ferrari, which had been his dream. Hamilton will spend 2025 settling in to fresh surroundings, and getting to know new colleagues. His superfast team-mate, Charles Leclerc, may sometimes outqualify him and even outrace him, but when that happens Lewis will be generous with his praise, just as he has not been churlish whenever George Russell has shown him a clean pair of Pirellis.

Statements at the ’20 Tuscan GP

Getty Images

and at the 21 Qatar GP

Lewis Hamilton

“If Ferrari gives Hamilton and Leclerc a good car in ’25, they will win races”

If Ferrari gives Hamilton and Leclerc a good car in 2025, they will win races. But 2026 will be the key. There is an old racing adage that says, “When F1 introduces a new formula, Ferrari wins.” It does not always happen but Vasseur will have convinced Hamilton that, in 2026, when not only power units but also chassis will have to comply with radically different technical regulations, the fastest car will be the red one.

And if it is, then one of the drivers whose CV is most suited to recommending and ushering in successful approaches learned from his current team, thereby helping to eradicate some of his next team’s operational and strategic shortcomings, is Hamilton, who may well then win the record eighth F1 world championship that many fans and insiders firmly believe was unjustly wrested from him in Abu Dhabi in 2021.