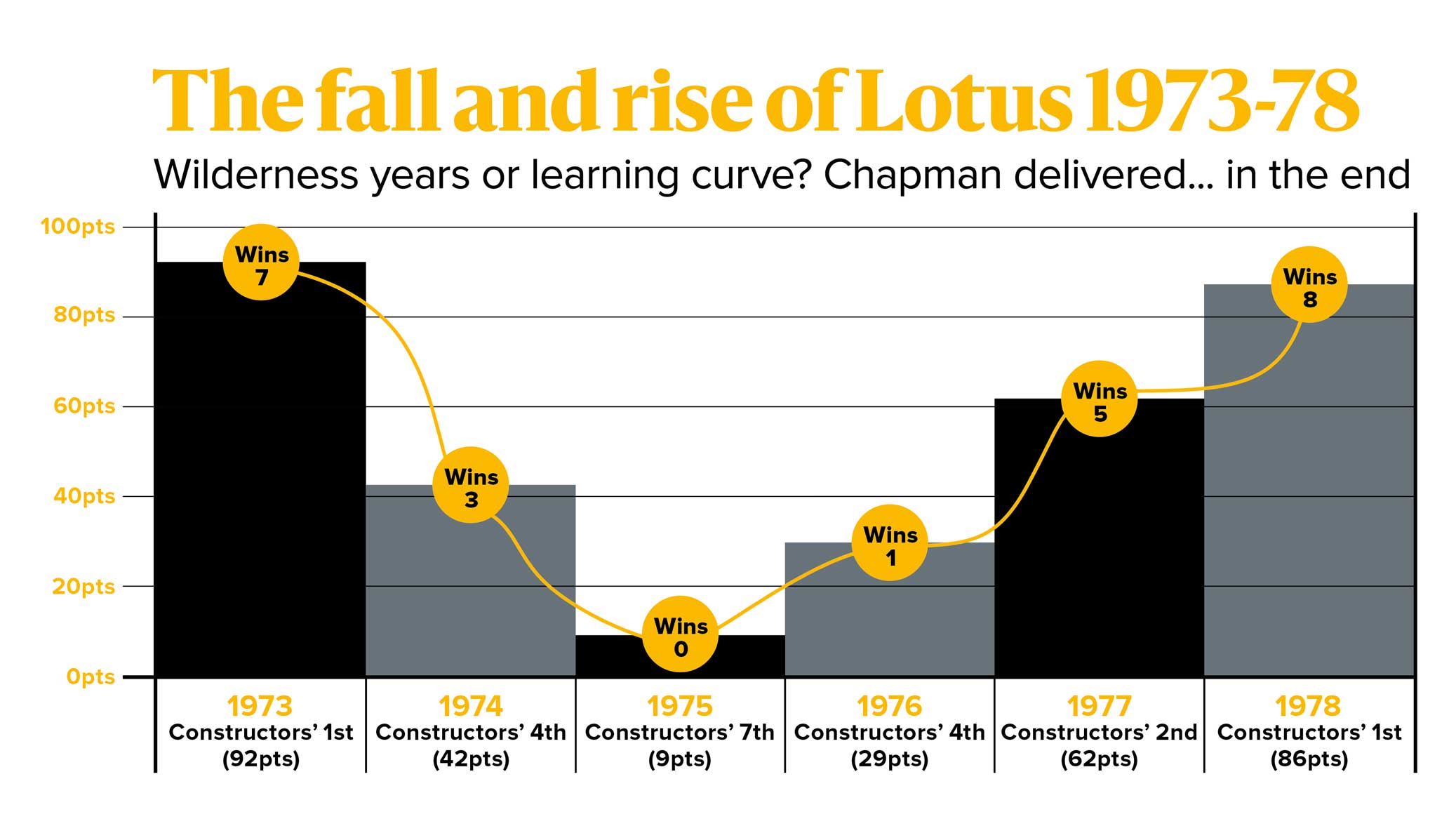

Lotus 76: the overlooked car that laid a path to F1 success

By 1975 Team Lotus had gone from Formula 1 high-flyers to flops and the 76 shouldered the blame. But as Gary Watkins sets out, it lay the foundations for glory

Ronnie Peterson at the 1974 South African Grand Prix – the debut of the Lotus 76

Grand Prix Photo

The Type 76 occupies little more than a footnote in the Lotus story. Quietly forgotten by the team back in 1974, it’s overlooked in the history books today. It is remembered as the car deemed not good enough to replace the once-great but ageing 72 over the course of that season. Yet the 76 might just be up there among the most important Formula 1 designs in the Team Lotus narrative.

But for the shortcomings of the 76 – real or otherwise – Lotus might never have stolen a march on the rest of the F1 grid in the development of ground-effect aerodynamics. It was the failure to effectively replace the 72 that motivated Lotus boss Colin Chapman to instigate a root-and-branch development programme to re-assess F1 design. The first fruit of that was the Lotus 78, a machine that turned the team back into a regular race winner in 1977. The year after came the type 79, the car that gave the team its first world titles since taking the ’73 constructors’ crown.

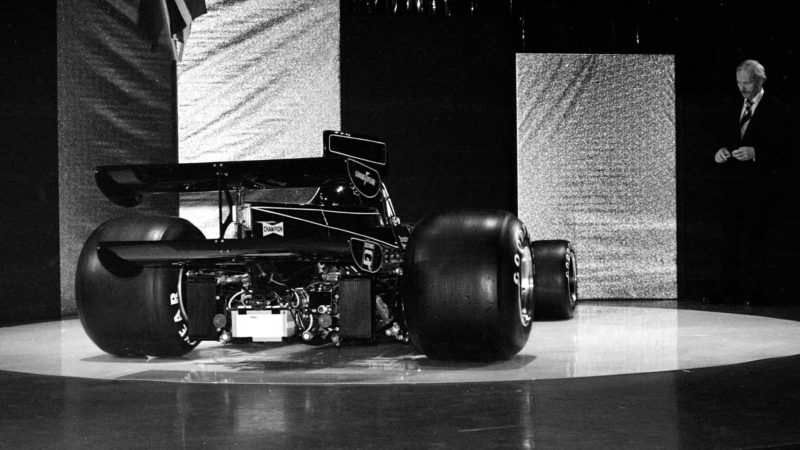

The 76, with twin wing, at a John Player Special Lotus presentation in 1974; Colin Chapman was about to be given one of the sternest tests of his career

Revs Library

The Cosworth-powered Lotus 76 was pivotal in that story. Team Lotus had abandoned the car during 1974, reverting to the proven if not always quick 72 in stages over the campaign. The new car, conceived as a 72 for the modern era, was parked once and for all at the season’s end, the team heading into 1975 with the old lady and ending up with a car in so-called F-spec. Yet it would be far from correct to suggest that the 72 raced in a single configuration over the course of its swan song season.

Team Lotus threw everything bar the kitchen sink at the 72 in what would be its final season before the introduction of the stopgap 77. Lead driver Ronnie Peterson even demanded one day in testing at Paul Ricard that the car be put back to how it had been in ’73, because he reckoned that was the best-handling 72 he’d ever had underneath him. He loved the machine Team Lotus prepared for him, but ended up going slower than in the latest offering.

Peterson admired the 72; his patience with the 76 quickly wore thin

Getty Images

It was against this backdrop and the jettisoning of the 76 that Chapman decided in mid-1975 that it was time to think again. The arch-innovator wanted to find the next breakthrough, the unfair advantage Team Lotus had enjoyed with the 25, 49 and 72.

The plan was concocted in Spain during Chapman’s summer holiday at his Ibiza villa. That’s how the late Peter Warr, Chapman’s able subaltern over two periods at Team Lotus and eventual successor at its helm after his death, tells the story in Team Lotus: My View From The Pit Wall published posthumously in 2012. Warr recalled his workaholic boss becoming quickly bored sitting by the pool. Instead he set to work on a document that would eventually change the face of F1, and much of the rest of motor racing, too.

“Chapman set to work on a document that would eventually change the face of F1”

“What he had done was to spend the time insulated from the pressures and mundane irritants of the office to produce in 30 handwritten sheets of his standard Oxford feint-rule and margined notepads (on which his job lists were always kept) the thesis and design philosophy that was the basis for the Lotus 78 ground-effect car,” wrote Warr in the work completed after his death in 2010 by long-time Motor Sport contributor Simon Taylor. It was, Warr suggested, “the product of boredom” but was also borne of the “frustration at no longer being in the spotlight of championship success”.

Peterson took the 76 to its sole finish, at the ’Ring.

The next step was to set up a new department to explore the ideas. It would be based away from the day-to-day concerns of the F1 team, a stand-alone operation focused on the future a couple of seasons hence.

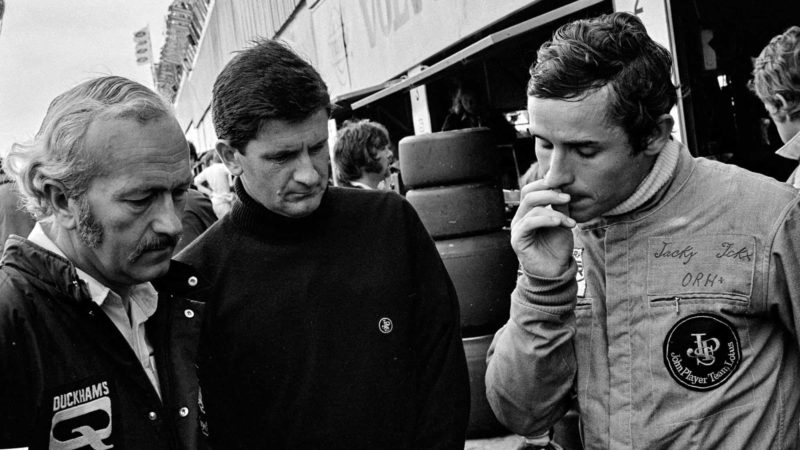

from left: Chapman, 76 designer Ralph Bellamy and Jacky Ickx; Bellamy believes Lotus had little passion for the car

Revs Library

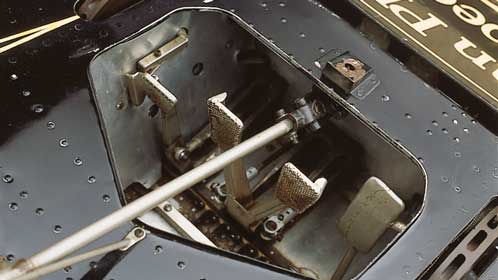

Lotus 4 pedal system

Rev library

A four pedal system allowed left-foot braking

Revs Library

Tony Rudd, who’d led the BRM F1 team both technically and managerially through its 1960s pomp, was brought in by Chapman to lead the project. He’d been recruited by Lotus in 1969, not to work in F1 but as powertrain manager on the road car side. He was subsequently promoted to overall engineering director at Lotus Cars, but in mid-1975 he was given a new position.

“Chapman would talk to anyone who’d listen about what was wrong with the grand prix car”

Rudd, who died in 2003, was worried when he was summoned to see Chapman in the summer of ’75 that he was going to get the “armchair and sherry treatment”, he recalled in his 1993 autobiography It Was Fun! My Fifty Years of High Performance. But instead of getting a dressing down, Chapman told him, “You’ve had a long enough holiday from F1. It’s time you got down to some serious work.”

Peterson qualified 16th at the 1974 South African GP; he’d collide with Ickx at Turn 1

Rudd brought in Ralph Bellamy, designer of the 76, and another ex-BRM man from elsewhere within the Chapman empire to work in the new R&D department set up at Ketteringham Hall, which was still more than a year away from becoming home to the Team Lotus race team. Peter Wright had followed Rudd out of the door at BRM, initially going to Specialised Mouldings before his subsequent recruitment by Chapman for his Technocraft operation to experiment with injection moulding for car bodies and boat hulls. It wasn’t part of Group Lotus but known as an ACBC company (Chapman’s initials).

“Tony’s brief was to rethink the grand prix car: we went back to first principles,” recalls Wright. “Chapman would talk to anyone who’d listen about what was wrong with the grand prix car. He didn’t know the answers. I think that because the 76 had proved to be no better than the 72, it stirred Chapman to install Tony up at Ketteringham Hall and say we’ve got to rethink this.”

Rudd and Warr’s accounts of the fabled document in Chapman’s famously neat hand diverge, however. And that’s beyond Rudd putting it at just the 28 pages!

Warr insisted in his book that what the world came to know as ground-effects was a big section of it: “The first considerable part was concerned purely with the theory of obtaining downforce from below the car with less drag than had been possible hitherto with surface aerodynamics.”

Rudd, on the other hand, suggested that the predominant aerodynamic question posed in Chapman’s document was: “Which is best, a full-width chisel nose or a needle nose with two big aerofoils?”

Wright today suggests that Rudd’s memory of Chapman’s document was the more accurate when it came to writing their respective autobiographies. The aero study was, he says, focused on overcoming the understeer that increasingly plagued the 72 during its fading years, and the 76 as well.

It was the Spanish GP, a month on from Kyalami, where the 76’s reputation was set – but it led for some of the race

Grand pirx photo

“The key requirement for the new car was that the aero load on the front should increase under braking,” says Wright. “We were looking at what height the front wings needed to be so that when the car braked you got more downforce to put more load on the front tyres.”

So he and Rudd were in reality looking at ground-effect because “as the front wings come closer to the ground the more downforce you get until, that is, they get too close”. But not in the way Team Lotus would eventually exploit underbody airflow on the 78 and 79.

That came about, at least partially, by accident. Wright had experimented with ground-effect with Rudd at BRM: the unraced P142 of 1969 was canned at the insistence of the team’s new signing John Surtees. Wright returned to the theme on the bodywork he produced in double-quick time for the March 701 at Specialised Mouldings. It was only natural that he should resurrect this line of thought in his new role at Lotus.

“We researched what to do with the nose, then the radiators and where to put them on the side of this pencil thin monocoque that Ralph had designed,” he says. “Then you need somewhere to put the fuel in the car, so you end up with a sidepod. Making the sidepod wing-shaped was the obvious thing to do, because we knew it couldn’t do any harm.” That it could do what Wright calls “something really positive” was an accident.

Ickx in practice at the 1974 Spanish Grand Prix running a 72 wing on his 76 but retaining the Chapman-inspired nose.

Grandprixphoto

“We were modifying the sidepods on the model and they became a bit flakey,” he remembers. “We noticed the results in the windtunnel were changing a lot and then that the sidepods were sagging. That was the eureka moment when we realised the gap between the sidepod and the floor really mattered. So we sealed the side with some card – rudimentary skirts, if you like – and braced the sidepods, and we doubled the downforce, or something of that order. Then we were off.”

Yet had the 76 successfully replaced the 72 would Chapman have spent his holiday in ’75 theorising on the future of the F1 car? The answer to that one can be no more than conjecture. Nor can it be known if the Lotus 76 could have been a championship or even a race winner had Team Lotus persevered with the design rather than switching back and forth from the 72 prior to its eventual abandonment. It’s fair to say that it wasn’t given a fair crack of the whip. The car fell foul of internal politics at Team Lotus.

Team manager Warr took against the machine, or maybe its designer. Peterson was arguably complicit in this. He loved the 72, at least in the form that he’d first driven it when he arrived at Lotus in 1973, and was always happy to revert to the 72 rather than putting in the hard graft trying to develop its successor. And Warr loved Peterson…

Bellamy led the design of the 76, though it wasn’t called that originally, nor in the official bumf from sponsor John Player. The initial 76 drawings had 75 written in the corner after a mix-up with the automotive division in what was the next available Lotus type number, while the two cars built were officially John Player Specials, numbered JPS/9 and JPS/10 (there had been eight 72 chassis up to that point).

“Colin came to realise that the 72 was past it through the 1973 season,” explains Bellamy, who joined Lotus in ’72. “About halfway through the year, he said we needed another car. The requirement for what turned out to be the 76 was to make a car that was like the 72 only better engineered and more reliable” – and also lighter.

“It was Chapman’s way to give people targets they couldn’t hit,” says Geoff Aldridge, who drew the 76 chassis under Bellamy’s direction. “I remember him saying that he wanted it to be 100lb [45kg] lighter in fairly strong terms.”

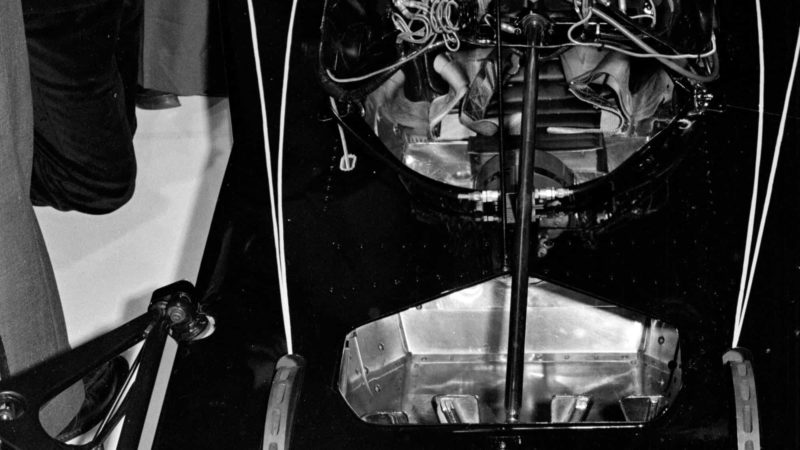

The tub was more rigid and easier to work on, too. “Being a bigger monocoque it was stiffer,” says Bellamy. “The bag tank on each side of the car didn’t go any further than the dash bulkhead, which freed up access to the torsion bars.” Front suspension adjustments on the 72 had always been a bugbear of Team Lotus mechanics because the suspension elements protruded into cut-outs in the forward-reaching tanks.

The 76 was simpler than the 72 in many ways, yet more complex in others. Chapman wanted an electrically activated clutch to allow for left-foot braking, something trialled on the 72 back in ’73. That explained the button on top of the gearshift and twin brake pedal set-up, a vee-shape affair either side of the steering column. The button triggered the starter motor, which ran in reverse to drive a hydraulic accumulator that activated the clutch.

The car’s aerodynamics appeared radical too, at least to start with. There was a biplane rear wing along with an unusual-looking nose.

“The biplane arrangement was just something that I thought might work; we weren’t all that flash in terms of aerodynamics in those days,” explains Bellamy. “It didn’t last long. The mounting was usable for anything, so we just put a 72 wing on it.”

The slightly weird-looking nose of the car resulted from another Chapman diktat: he designed the front aero himself.

“If you look at the early photos, the nose doesn’t appear to fit the rest of the car,” says Bellamy. “Colin gave me a lot of freedom in the design, but the nose was his contribution. He had this idea that came from boats, which he was very much into at the time [JCL Marine, makers of the Moonraker and Marauder boats, was another ACBC company].

“He called it the ventilated step. He thought that if it worked on the underside of a boat it would work on the top of a racing car. That was Colin.”

The 76’s radical design elements gradually disappeared through the season. The hydraulic clutch proved problematic from the start. The biggest issue, remembers Bellamy, was that there was no in-built bleed mechanism.

“It kind of bled itself through running, so it would eventually work, but in those days we were changing a Cossie every 600 miles,” he says. “So the air would get back in and we’d never get to do any proper testing with it.”

Peterson persevered with the system through practice and qualifying on the car’s arrival for round three of the ’74 championship at Kyalami, before it was abandoned for a race in which he and team-mate Jacky Ickx came together at the first corner. It was an inauspicious debut for the car. Yet its reputation as a failure – at least within Team Lotus – was founded on what happened at its subsequent grand prix outing in Spain.

Next up, though, was the non-championship International Trophy at Silverstone on April 7. The race is remembered for James Hunt’s victory for Hesketh and his pass on Ronnie Peterson. No one recalls that ‘Super Swede’ was driving a 76 – complete with the twin-wing – and not a 72.

The unusual rear aero had disappeared for Jarama, as had the semi-automatic transmission. Peterson put the car on the front row and then led for the first 20 laps on wet tyres until pitting for slicks. Yet the die was cast for the car on the outskirts of Madrid.

It had rained on race morning, and when the Lotuses arrived on the grid following reconnaissance laps on a wet track, Chapman noticed the oil temperatures were low. The reason, explains Bellamy, was that the oil coolers were being doused in water from the rear tyres, but his boss insisted on having the rads tapped to bring up the temps.

“Off they go, the track dries and, lo and behold, both cars experience overheating,” recalls Bellamy. Peterson would retire with engine failure, two and a half laps after a botched tyre change had dropped him down the order. Ickx, who’d been fourth before the stops, also ran into overheating problems.

“The 76 was never really in favour. It wasn’t given a fair chance”

“One of the criticisms of the car was that it overheated, and that was down to Colin and the tape,” continues Bellamy, who was told to go away and redesign the cooling system while Team Lotus reverted to the 72 after the following GP at Nivelles in Belgium.

The 76 was crucified on further crosses: its weight and its tendency to understeer. Bellamy has answers for those criticisms, too.

With little trust in the 76, Peterson was pleased to be back in his beloved 72 at Monaco – and won

Getty Images

“It was heavier, but that was only with the electric clutch on it,” argues Bellamy. “When [engineer] Nigel Bennett arrived at Lotus in ’75, he saw a 76 sitting around and asked what was wrong with the car. I said, ‘Mate, don’t go there.’ He got the guys to roll it onto the scales and found it was no heavier than a 72.”

The 76 understeered for the same reason as the 72 did, Bellamy believes. Lotus had won the 1970 and ’72 drivers’ titles on Firestone tyres, but with a switch to Goodyears for ’73 it had gradually dropped down the development pecking order. The late arrival of the 76 and Emerson Fittipaldi’s defection to McLaren only hastened that slide.

Peterson placed his 76 – with twin-wing – on the front of the grid at the International Trophy in April ’74 but was out after 30 laps

Grand prix photo

“Goodyear did much of their winter testing with McLaren and Emerson, and came up with a tyre that suited the M23,” he explains. “It was a more robust tyre. That didn’t work for Lotus with the inboard front brakes and its low unsprung weight. The Lotus 76 understeered: we couldn’t get any heat into the tyres because we didn’t have the brake disc inside the wheel.”

The return to the 72 for Monaco resulted in one of Super Swede’s most memorable victories and a more or less permanent switch to the old car for the team leader. Peterson did score the best result for the 76 with fourth at the Nürburgring, but only after he’d crashed his 72 heavily in practice and the team had bolted the rear end of the old car to the front of the new. Ickx would race the same bitza special in Austria and Italy, while Tim Schenken drove the other chassis in similar spec – illegally after taking the start as second reserve – at the Watkins Glen season finale.

With lessons learnt, the 78 was introduced in ’77 – F1’s first ground-effect car. Lotus was back in business

Getty Images

Team Lotus didn’t entirely give up on the 76, despite Peterson’s victories aboard the 72. After some decent testing, it took both new chassis to Monza and only a single 72. It was with the old car that Peterson followed up on his Monte Carlo and Dijon wins in the Italian GP. The Swede abandoned the latest car after first practice and then on the eve of the race decided to ditch a wide track rear suspension set-up on the 72 that had come on stream for the French GP. Victory three of ’74 followed.

The decision to go back to the 72 looks like the correct one given Peterson’s trio of wins, yet Bellamy insists that the old car was no better than the new. Or rather “no worse” given both cars’ struggles with the Goodyear fronts. He puts the Monaco victory down to Peterson’s hustling driving style: “Being a slow circuit, Ronnie could hurl the car around and overcome the front tyre issue.”

Bellamy claims there was “no enthusiasm for the car” and that Warr took against it: “He didn’t want anything to do with the 76”.

And then came the 79 in the 1978 championship, which gave Mario Andretti his first and only F1 world title

Getty Images

The designer of a car is going to be biased, though Aldridge suspects that Bellamy is correct when he suggests that it was a victim of politics: “It was never really in favour. It probably wasn’t given a fair chance.”

Warr largely skirted around the topic of the 76 in his autobiography. Instead, he reserved more space for a not entirely complimentary commentary on Bellamy’s talents. He goes on, however, to admit the Aussie’s importance in the design of the 78. “The more rarefied air of the newly formed development area at Ketteringham Hall, away from the daily stress of the F1 workshop and race track, was perhaps the environment he needed to produce his best work,” he wrote.

The Lotus 78 undoubtedly was the pinnacle of Bellamy’s career. The 76 could be described as the nadir, but without it he would probably not have got the chance to design a revolutionary racing car in the 78.