Overlooked? A 10% tolerance on the 70-limit

Sir, Might I point out through your correspondence columns that it is very unlikely that Motorists would be convicted of exceeding the 70-m.p.h. limit unless their true speed was in…

Getty Images

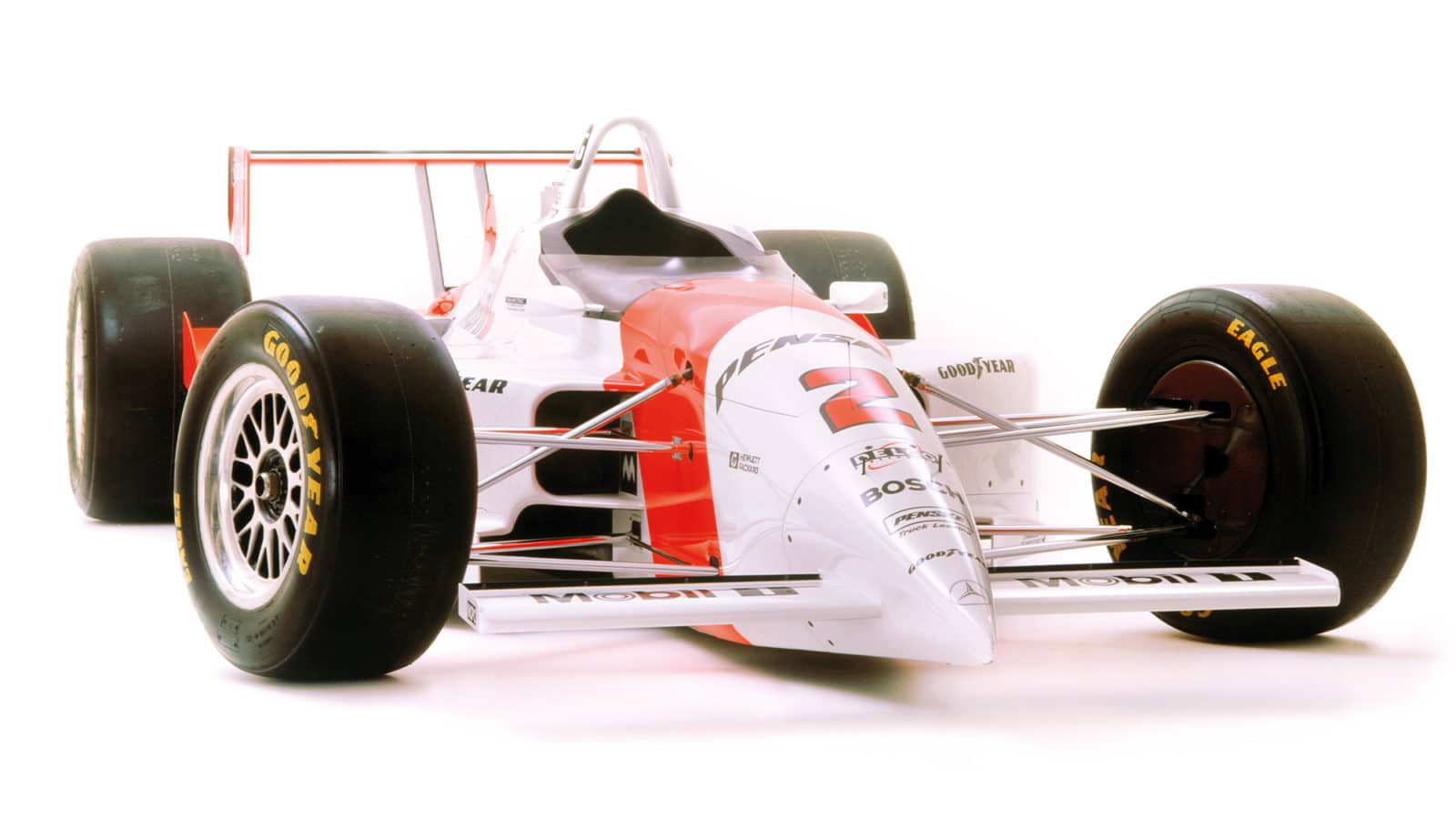

While I understand that for many the world of motor sport begins and ends with Formula 1, I was a little surprised to read that the excellent Mark Hughes appears to be also somewhat restricted by this boundary. His article King size allies (March) could have concluded with the acknowledgement that Philip Morris and its “iconic chevron Marlboro design” did have a life beyond F1. In 1989 Team Penske and Philip Morris began their 20-year association [shown above on the 1997 Indycar] during which period they won the Indianapolis 500 eight times, a partnership greater, and perhaps more successful, than that with any Formula 1 team.

I read with interest the editorial in the March 2022 issue with regard to the question as to whether there is a pro-British bias within Formula 1 [The Editor]. It is never easy to pin down bias as like luck it is something you never notice when it is in your favour but is impossible to ignore when you perceive it to be against you. As far as the magazine is concerned it will always appear to favour one driver over another when one driver is of the same nationality as the magazine.

Journalists have to tread a fine line when reporting facts under these circumstances and it can be quite easy to let bias sneak into reporting, even unknowingly. Of course bias can occur when a journalist has no apparent preference for a particular driver in terms of nationality, as we saw in the reporting of the tragic season of 40 years ago. Then there was much comment about the betrayal of poor Gilles Villeneuve as opposed to the duplicity of Didier Pironi. There is no easy solution to apparent bias as it will always be a matter of perception. Sport being no different to politics, it is something that you will always have to be vigilant to avoid while accepting that it is impossible to please everybody.

Gilles Villeneuve in his Ferrari at the San Marino Grand Prix in 1982 – the infamous ‘betrayal’ race

Grand Prix Photo

Your feature on the 250 GTO [King crimson, March] took me back to a stay in Paris in 1964. One afternoon I was sitting at a roadside restaurant on the Champs-Élysées sipping a costly beer when two likely lads in a 250 GTO with Portuguese plates pulled up at an adjacent traffic lights alongside a US-registered Pontiac GTO. The driver of the Ferrari clearly indicated that he wanted a traffic light GP and when the lights changed set off like a scalded cat, leaving black stripes on the road and a mystified American who pootled off at a crawl. Many hours later, walking back to my host’s apartment after an unsuccessful foray into Parisian romance and with the streets largely deserted, I was greatly cheered by the howl of a V12 and watched the same Ferrari in a well-controlled drift crossing the Seine. Boys having fun.

Later on that year I saw Mike Parkes in Colonel Hoare’s car winning a GT race at Snetterton with some ease. He half-spun at the hairpin on the warm-up lap but was faultless in the race exiting the bend in glorious power slides. Mike may not have had the smoothness of Stirling in his 250 SWB but was very fast and his exuberant style was great value for the spectators. Good memories.

I recently re-watched a 2008 Formula 1 season DVD and was interested to see a certain young driver out-braking himself, running wide at corners and forcing drivers off track in his efforts to win his first championship. He is now one of the greatest drivers of all time. Let’s see if Max can achieve as much in the coming years.

I watched the launch of the new Red Bull F1 car where Max Verstappen was introduced as world champion. My immediate reaction was “but he’s not really the world champion” even though I know that the arguments are done and dusted and Max is world champion. He is a great driver and will no doubt go on to win many world championships but what a pity that his first was won this way.

The plaudits for Graham Hill and his performance in the 1960 British GP continue. Here’s Gordon Lang’s shot of BRM chief engineer Tony Rudd in Hill’s car before the race

I was interested to read the letter in the March edition of Motor Sport regarding the 1960 British Grand Prix which was so very nearly won by Graham Hill after an amazing drive. He had stalled on the grid and subsequently passed everyone to take the lead only to spin off the track within sight of his first victory. I took the attached photo [above] in the paddock of Tony Rudd, the BRM chief engineer, taking one of the cars out on track for a test run. I always used to buy a paddock pass in those days as everything and everybody was so accessible to the enthusiast then, unlike today.

I read with keen interest Dr John Christie’s reference in March [Letters] to the P48 BRM brake failure that deprived Graham Hill of victory at the 1960 British Grand Prix. A strong fan of BRM, my father took me to Goodwood for, I think, an Easter meeting, when the BRMs were racing. Positioned in the grandstand overlooking the chicane we were able to see the race cars hurtling down Lavant Straight and the drivers’ daring overtakes under braking and as they approached the short straight before the brick-built chicane.

Jean Behra’s BRM suffered total rear transmission brake failure at the end of Lavant Straight; by genius he managed to negotiate the corner but his mighty speed was such he slammed into the chicane, bursting it and coming to rest within a few feet on the grass at the pit entrance. A gasp went up, then a great cheer as Jean stepped out seemingly unharmed but doubtless shaken. It was always a mystery to me why BRM persisted with this set-up. The low weight benefit of this clever idea is not in dispute, but it was a shame that the technology of the time was not quite there. Shades of the 16-cylinder car’s torque shredding its Dunlop tyres. The P48 was and still is a beautiful-looking grand prix car, probably my favourite even today.

Goodwood provided wonderful racing when I was in my teens. Sad at times as well. I was there when Stirling had his horrendous career-ending crash. The crowd remained silent during his removal from the wreck and journey onward to hospital; his survival seemed greatly in doubt at the time. The slow pace of the ambulance down Lavant Straight remains with me today, as does the sense of shock and disbelief.

On a more light-hearted note, McDonald Hobley, the renowned BBC television broadcaster, regularly commentated from a box mounted on stilts three-quarters of the way down Lavant Straight. During a sports car race a driver lost control under braking and veered left taking the stilts from under Mac’s box. The commentary was hilarious even as it all toppled over.

Broom service: Jean-Claude Rude’s cycling speed-record attempt in 1978 behind a Porsche

Porsche

Loved the March Parting Shot pictures of the cycling speed record attempt. It looks like some serious technical innovations went into converting the Porsche 935 Turbo. What amused me was the smaller picture [above] of the motorcycle pillion passenger pushing the cyclist with a broom to get him started. Not so technical, but if it works, it works!

I wonder if any other readers were struck, as I was by the photograph in February’s Parting Shot of the driver’s briefing for 1960 Monaco GP. What is apparent from the serious looks on the faces of the assembled drivers, is that motor racing was a dangerous sport. Even the normally ebullient Hill looks grim, Brabham more so. Lest we forget, two of those present [Wolfgang von Trips and Jo Bonnier] would perish while racing. An image at odds with the common perception that racing in the ’60s was all jolly good fun and not too serious.