Home & Away: Peter Whitehead's Cooper-Jaguar and its racing adventures

Yorkshire pro Peter Whitehead’s 1955 Cooper-Jaguar was a European co-star but became an Australian winner, then disappeared before resurrection in the 1980s. Mark Bisset tells the tale of the most successful of the six Jaguar-powered racers

The Cooper (No11) of Peter and Graham Whitehead only lasted four hours at Le Mans ’55–a dark day in racing history

McDonald Collection

Peter Whitehead pitted his Cooper-Jaguar T38 at Le Mans in 1955 just after a catastrophic chain of events had catapulted Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR through the crowd at 6.26pm. The accident cost 85 lives and destroyed many more.

After completing only 38 laps, Peter and stepbrother Graham Whitehead’s Cooper-Jaguar race was over almost before it started. In the fourth hour, running 14th, losing oil and oil pressure, they were black-flagged, a big disappointment for the man who with Peter Walker had won the 1951 endurance classic aboard a works Jaguar C-type. It was also an augury of the fate of a programme begun at Peter’s initiative in late 1953.

Usually characterised as a ‘wealthy gentleman driver’, Yorkshireman Whitehead was a fast, reliable seasoned pro – of that age group whose best years were taken by the War. In its 1950s heyday Peter’s family firm W&J Whitehead, a large Bradford wool-scouring and spinning business, employed 1200 people. Whitehead applied similar business acumen to his racing, enjoying profitable fun for years before and after World War II contesting non-championship single-seater and sports car events around the world, selecting those with good start and prize money. With his experience of C-type and Jaguar’s experimental XP/11 design he thought a Jaguar-powered car which was lighter and better handling than the C and forthcoming D-types would be ideal for these sports car events. Both C and D had live rear axles, so the Cooper’s independent rear suspension should have better traction.

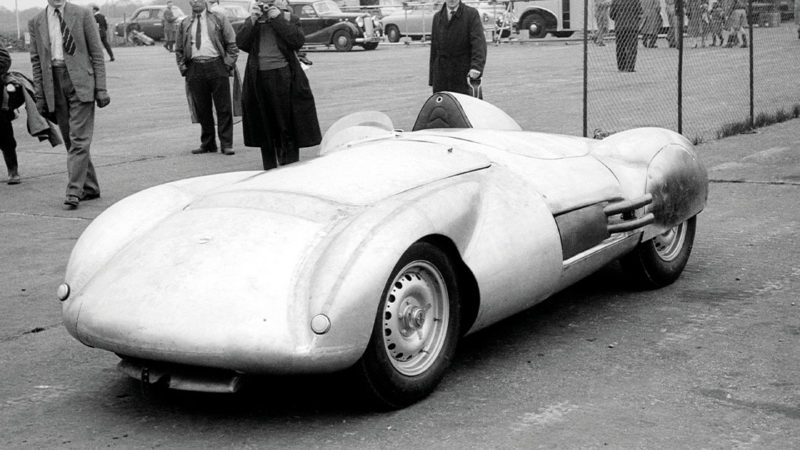

Peter Whitehead’s new Cooper-Jaguar attracts attention at the International Trophy at Silverstone in 1954

Getty Images

Well familiar with Coopers, having raced a T24 Alta in 1953/4, Whitehead approached the Surbiton firm with his idea. Charlie Cooper grumbled about brand damage if the sports car wasn’t successful, but John and Cooper designer/draftsman Owen Maddock soon met with Whitehead and his racing manager David Yorke to flesh out the brief.

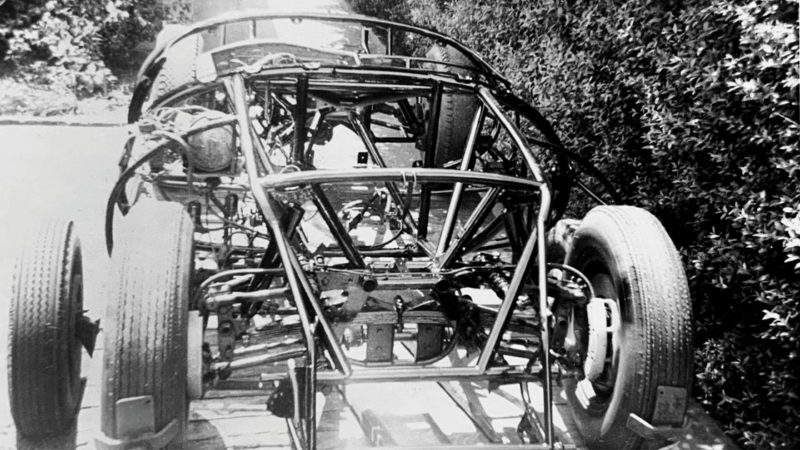

The essential element of the resultant Cooper-Jaguar Mark I (Type 33) was a strong, light and typically curvy spaceframe chassis made of 1½-inch steel tubing with four main longitudinal members and oval outriggers between the front and rear wheels. Double-wishbone suspension sat front and rear, with transverse leaf-springs and Armstrong shock absorbers. Thanks to his experience with disc-braked C-types the year before – fourth at Le Mans, wins at Reims and Goodwood – Dunlop discs were mandatory for Whitehead despite a cost of £750, a big chunk of the £4000 price.

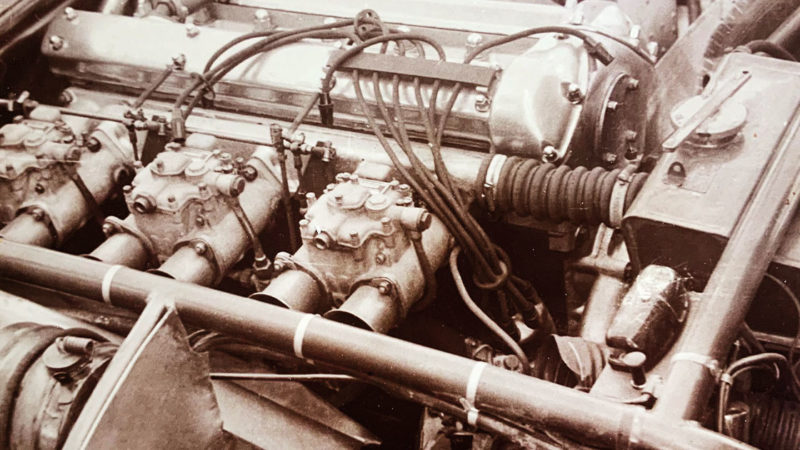

The heavy 3.4-litre twin-cam Jaguar XK engine, giving with its iron block and alloy heads about 225bhp, sat well back in the frame, the gearbox attached to the cast-alloy Cooper/ENV diff via a short driveshaft, while a quick-change rear end made for fast final-drive ratio changes. A four-gallon oil reservoir and 37-gallon fuel tank held the vital fluids.

With the T38, Cooper and Jaguar was a good fit of two British powerhouses; a 3.8-litre engine was a tight fit, canted at an angle

McDonald Collection

Clad in a swoopy 18-gauge aluminium body it looked the goods, weighing 17cwt, about 1.5cwt less than a C-type and 1cwt less than a D. Three of this version were built.

Whitehead’s Type 33, CJ-1-54, first raced in the May 1954 Silverstone International, then the Circuito do Porto and Circuito de Monsanto in Portugal, the Snetterton International, Wakefield Trophy, and Aintree International at home, and finally the GP Penya-Rhin in Barcelona.

First place in the Snetterton 20-lapper was his best result, while Ferraris ruled at Silverstone, Monsanto, Aintree and Penya-Rhin. Villoresi’s works Lancia D24 won at Porto, and Gallagher’s Gordini T15S took the Wakefield Trophy at Curragh, Ireland. The Cooper-Jaguar would need to up its game.

For 1955 a Mark II or T38 appeared, its dry-sump engine canted eight degrees to the right to lower the bonnet line. Breathing through three 45DCO3 Webers, it gave about 250bhp, and Cooper assembled another three of these. By now these T38s had Jaguar’s official blessing: Whitehead’s mount, CJ-1-55, took its bow naked, sans curvaceous body, on the Jaguar stand at the Brussels Motor Show in January.

Peter Whitehead’s year got off to a flyer in New Zealand in 1956, with the Cooper T38 finishing second at Ardmore on January 7 behind Stirling Moss in a Porsche 550

McDonald Collection

Despite the cancellation of many races following events at Le Mans, CJ-1-55 – which made its debut in the Silverstone International in May – contested the Circuito do Porto and Circuito de Monsanto in Portugal, the Goodwood 9 Hours, the Oulton Park and Aintree Internationals and the Tourist Trophy at Dundrod.

Honours in Whitehead’s T38 races were more widely spread than in 1954. Silverstone, Oulton and Goodwood fell to the Aston Martin DB3S, Jaguar D-types won at Le Mans and Aintree, and the Ferrari Monza at Hyères. A Maserati 300S was victorious at Porto. Mercedes-Benz returned for the season-ending Tourist Trophy championship round, winning with the 300 SLR – a timely step back to centre stage for the sports car of the year.

Whitehead’s best was fourth in the Circuito do Porto, while a competitive run at Dundrod was ruined when a chassis tube broke. Crystal clear to Whitehead was the depth of competition. Works commitment was needed to break into the leading sports car pack, but Cooper had bigger fish to fry in single-seaters. Coventry-Climax had good customer F2 engines and Cooper was happy to build suitable chassis. With increasing success, Formula 1 was next.

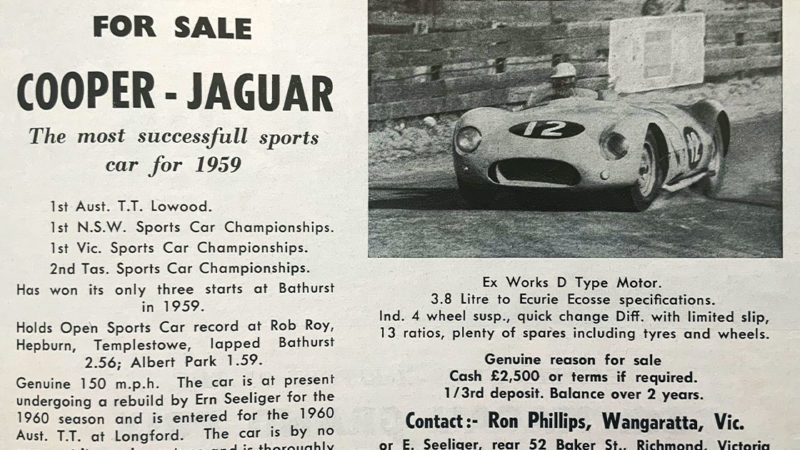

Newspaper classified from Ron Phillips in Victoria, offering the “most successfull [sic] sports car for 1959” – and yours for £2500. Australia moved to the dollar in 1966

Peter’s relationship with Ferrari – he was the first privateer to buy a Formula 1 car from Maranello, in 1949, and won the Czechoslovakian GP that year – produced a pair of 500/625 3-litre four-cylinder Formule Libre cars. Mildly updated, the same cars made the ’56 trip. In addition, Whitehead took CJ-1-55, and Gaze his HWM-Jaguar VPA9; the plan was to race, win and collect, then sell all four cars.

Whitehead’s machines were beautifully prepared by Stan Elsworth and Arthur Birks at his Motor Work garage in Chalfont St Peter, then despatched to Auckland for the NZ GP at Ardmore Airfield on January 7, 1956.

The grid included Whitehead and Gaze, Stirling Moss aboard the family Maserati 250F, Reg Parnell in the one-off prototype GP Aston Martin DP155, Leslie Marr’s Connaught B-type Jaguar and Jack Brabham’s Cooper-Bristol T40.

While Moss disappeared into the distance, winning the 186-mile race from Gaze and Whitehead, CJ-1-55 had an unexpected NZ GP support role. After Parnell’s Aston Martin misbehaved in practice, Whitehead loaned his pal the car; he raced it to fifth place. Moss raced Australian Porsche importer Norman Hamilton’s Porsche 550 Spyder to victory in the sports car race from Whitehead’s Cooper and Gaze’s HWM. These performances were more than enough to convince Stan Jones, father of F1 world champion Alan, and 1958 Gold Star and 1959 Australian GP winner to buy the Cooper-Jag. Jones raced and traded many racing cars, making most of them sing, and the Cooper would be no exception.

The start of the 1955 Tourist Trophy at Dundrod – No3 is the Cooper-Jaguar of the Whiteheads; the Mercedes (No10) of Stirling Moss and American John Fitch is opposite; and centre is the Ferrari of Umberto Maglioli and Maurice Trintignant

Getty Images

Whitehead and Gaze had a great summer. The Brit won at Wigram and Ryal Bush, and then on the Gnoo Blas road circuit in New South Wales, while the Aussie was victorious at Dunedin. To cap it off, they sold their cars, as did Moss and Brabham theirs. These colonial trips were manna from heaven for visiting racers and local competitors alike, selling and buying year-old racing cars.

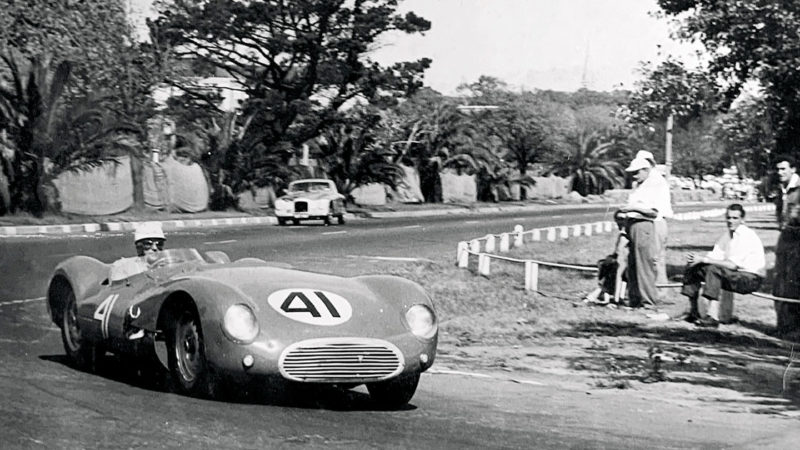

This pattern of Antipodean racing commerce was well established before the 1960s Tasman Cup. CJ-1-55’s debut in Australian hands was at Fishermans Bend in mid-February. Jones won the Lucas Trophy and sports car scratch, but retired from the blue-riband Victorian Trophy after clouting a hay bale. Before Albert Park’s March Moomba meeting Jones hillclimbed the Cooper at Templestowe and Rob Roy, close to his Melbourne home, taking class records at both. A staggering 100,000 people attended the first day’s racing at Albert Park, in a double-header a week apart. Gaze, in his last drives of the HWM-Jaguar (sold to multiple Australian Grand Prix winner Lex Davison together with his ex-Ascari Ferrari) won the 150-mile Moomba Tourist Trophy from Bib Stillwell’s Jaguar D-type, but the star of the show was Jones.

The pugnacious, stocky little racer had trouble getting the Cooper off the line in the Le Mans start, but then charged. He led by lap four, but driving unnecessarily hard, ran his engine’s bearings when leaves partially blocked the radiator, but the pace of the T38 was proved with a lap time two seconds clear of Gaze and Stillwell.

A week later, after the engine was rebuilt, Jones went at it hammer and tongs with Stillwell in the 50-mile Argus Cup, but Stillwell took the honours from Jones; Gaze was third. Stillwell and Jones set a new sports car lap record of 90.5mph. Jones then offered CJ-1-55 for sale. After the engine of his Maybach 3 let go at maximum revs at Gnoo Blas that January, Jones decided on a more competitive Maserati 250F. The Cooper had to go to help pay for the sleek red Italian.

CJ-1-55 passed quickly through John Aldis and Allan Gray’s hands without notable success, then central-Victorian racer Ron Phillips bought it in 1958. A Wangaratta motor trader like his father, a pre-war ace, he was stepping up from a Healey 100S. Now painted a distinctive light blue, she looked a little tatty about the body but the well-prepared, skilfully driven car found its sweet spot in Ron’s hands.

He opened the batting with third in the 100-mile Australian Tourist Trophy (ATT) at Bathurst in October behind David McKay’s Aston Martin DB3S and Derek Jolly’s 2-litre Lotus 15 Climax FPF – both ex-works cars. Second in the Victorian Tourist Trophy at Albert Park in November 1958 was equally impressive. Triple Australian GP winner Doug Whiteford’s Maserati 300S won.

Albert Park Moomba meeting in March 1956, with Stan Jones, father of later F1 world champion Alan, at the wheel – although he was down the field on this occasion

Edgerton Collection

Having got the hang of CJ-1-55, in 1959 Phillips brought home the bacon. He contested the Australian GP at Longford in March. Among the Coopers and Jones’s Maserati 250F Phillips started fifth, but didn’t finish due to diff problems. Jones took a well-deserved victory. At the Bathurst Easter meeting he won two races from Frank Matich’s Jaguar C-type – Matich, later Australian Sports Car champion, ATT, Australian GP and Gold Star winner was already respected so these were strong wins on the toughest of road circuits. In April Phillips squeezed in a race near home at Tarrawingee. The one-time Le Mans racer here ran on a part-dirt, part-bitumen surface, and Ron took wins in the Cooper and aboard Jones’s Maybach 4 Chevrolet.

In June the 100-mile ATT was held at Lowood, Queensland, and finally the bellowing blue beastie won a championship. Phillips took the 35-lap race from Bill Pitt’s Jaguar D-type and Bob Jane’s Maserati 300S. Phillips also saw success in the Victorian Sports Car Championship and the NSW Road Racing Championship for sports cars at Bathurst in October. In 1960 Australia’s sports car grids were little changed, although the Lotuses from Britain were on their way.

Phillips popped the Cooper on pole for the ATT at Longford but retired. Equipe Phillips then headed up the Hume Highway for Mount Panorama, again at Easter. Whiteford’s 300S won both their Bathurst encounters with Phillips second; the Maserati did 147.54mph, and the Cooper 150mph down Conrod Straight.

Ron Phillips from Victoria raced the by-now ‘blue beastie’ T38 at Bathurst in 1960, but the car was showing its wear and tear by this point

McDonald Collection

After a great run together Phillips offered the car for sale. Accomplished young racer and wheat farmer John Ampt was the purchaser at £1995, and he too extracted the best from the car, as he recalls. Ex-works Jaguar and Ecurie Ecosse mechanic Ron Gaudion had recently returned to Australia. “I got lucky there; Ron was happy to look after the car,” Ampt says. “The arrangement worked really well.”

The young farmer’s high-speed 250-mile drives towing the Cooper behind a Ford twin-spinner V8 became legendary before and after race meetings between Melbourne and the Mallee. He raced at Templestowe in September 1960, then Bathurst in October, taking off where Phillips left things, finishing second to Whiteford in the qualifying heat, and third behind Matich’s Lotus 15 Climax in the 13-lap NSW Sports Car Championship.

“It was a step up in power but the Cooper handled nicely, just like the [Lotus 11-like] Decca, only the corners seemed closer together!” John says, chuckling at the memory of his early drives.

He ran in the Ballarat Airfield International in 1961, again at Easter Bathurst, this time finishing second to Matich’s Lotus 15 in both races. In 1961 Gaudion rebuilt the engine, although his attempt to obtain a special wide-angle head from the factory was unsuccessful. About then, racer and panel-beater Murray Carter fabricated a new nose.

Greville Edgerton rebuilt the Cooper T38 after buying it in 1963 from John Ampt, stripping the car to its frame, even changing the colour of the frame from grey to black

McDonald Collection

CJ-1-55’s final appearance on the national stage was during Mallala’s October 1961 Australian GP carnival, but Ampt failed to finish. With single-seater aspirations, he took off for England, leaving the Cooper in his brother’s hands to sell. Melbourne’s Greville Edgerton was the buyer in 1963.

“It was bloody nice to drive!” he recalls. “Not long after I bought it the crank broke, so I stripped it back to the bare frame and rebuilt it. I changed the colour of the frame from grey to black. The engine was [by then] 3.8 litres – I bought five second-hand cranks to get one which wasn’t cracked! I ran at all the Victorian tracks. It wasn’t really suitable for Calder and Winton, both very tight, but it was great at Sandown. I remember the body used to rattle whatever we did to it, but it was a fantastic car.”

At the Easter Bathurst 100 Gold Star round he was unplaced, but was first in the over 3-litre sports car scratch, and third in the 10-lap feature behind Matich’s Lotus 19. With plans to race overseas, Edgerton sold the car to Norm Crowfoot. He had the ageing machine looking glorious in vivid red, but didn’t race it after meetings at Calder in 1963, and Lakeland, close to his Lilydale home, in August 1964.

Then the voluptuous machine disappeared from public view, still in Crowfoot’s garage, but forgotten by most until the resurgence of historic racing meant that Jaguar-powered racers were in demand. David Robison ‘found’ the car and purchased it from Crowfoot in 1977.

Edgerton sold the car to Norm Crowfoot, who gave the car a red paint job; by autumn 1964 it had retired

McDonald Collection

Complete but tired, CJ-1-55 needed an extensive, expensive rebuild. After some initial work the experienced racer/restorer Ian McDonald bought it in 1981 and commissioned Gavan Sala to restore the body and Sid Fisher the mechanicals. “It took a little over two years,” Ian says.

“I retrieved the original seats and Reg Hunt helped with the original Cooper green.” The T38’s modern debut was at Sydney’s Amaroo Park 1984 Tribute to Jaguar meeting. It regularly ran in Australian Grand Prix demonstration events in Adelaide and Albert Park, and Stirling Moss ran it in the Geelong Sprints where it bellowed in fine style down Ritchie Boulevard with Moss and McDonald at the wheel. McDonald sold the car in the late-1990s to Brisbane’s Frank Moore and it has made the occasional guest appearance, most recently at Albert Park in 2017.

A new lease of life for CJ-1-55 came in the 1980s after an expert two-year restoration

F Moore

The HWM-Jaguars were the most successful of the XK-engined sports car genre, but the Whitehead-inspired Cooper-Jaguars shouldn’t be forgotten. CJ-1-55 was the most successful of the six Cooper-Jaguars, even though an Australian Tourist Trophy win at Lowood doesn’t have quite the cachet of a Le Mans victory.

With some works support and development who knows what could have been achieved?

What happened to CJ-1-55’s drivers?

The globe-trotting exploits of the racers is tinged with tragedy

Stan Jones’ car sales empire knocked for six during Australia’s 1961 credit squeeze. After a stroke, Stan was cared for by Alan and Beverley Jones. Jones was just starting to break through in F3 when Stan died in London in March 1973.

Ron Phillips moved to the UK after a few Lotus single-seater drives in Victoria in the mid-1960s. He partnered Brian McGuire in a motor-caravan business in London during the same early-1970s period that McGuire combined with Alan Jones in the Australian International Racing Organisation. This grandly titled operation entered their F3 Brabhams. Phillips and McGuire died in the UK – poor Brian at the wheel of his F1 Williams FW04 at Brands Hatch in 1977.

Greville Edgerton chanced his hand overseas too. He raced an Elfin Mallala Climax 2-litre FPF in England in 1964 but returned not long after.

John Ampt raced Ausper T4 and Alexis Mark 5 FJ and F3 cars in Europe from 1962-64, then returned home. He still lives on his Rainbow farm.

And Peter Whitehead, pictured above? After two decades of racing, he died after Graham Whitehead crashed on a bridge during the 1958 Tour de France Automobile. Their Jaguar Mark I dropped into a ravine. Peter was killed instantly; Graham survived but carried that burden for the rest of his life. He died in 1981.