Ford GT Mk IV is America’s true-blue undefeated road-racing champ

The British have always been proud of their association with the Ford GT programme, but the Mk IV was pure Stars and Stripes. As Preston Lerner reveals, for a sports car that only raced twice, it made a hell of a racket – and it’s about to ride again

Bob Riley is the greatest American racing car designer of the postwar era, full stop. His portfolio bulges with drawings for cars stretching from the Coyote that AJ Foyt drove to victory in the Indianapolis 500 in 1977 to Daytona Prototypes that won the Rolex 24 nine consecutive times. And while he’s not exactly the kind of guy who wallows in nostalgia, he does have a soft spot in his heart for the Ford GT Mk IV.

In 1965, Riley was part of a small team of engineers who created the J-Car. Two years later, the J-Car was re-fashioned into the Ford GT Mk IV, which won Sebring and Le Mans before being mothballed without ever having been beaten. Now, Riley Technologies – the firm Bob runs with his son, Bill – is building a run of five continuation Mk IVs based in part on engineering drawings signed by Riley himself more than a half century ago.

“The Mk IV should be remembered as one of the all-time great sports cars,” Riley says. “It feels right to have all the stuff we need to build the new ones here in our shop.”

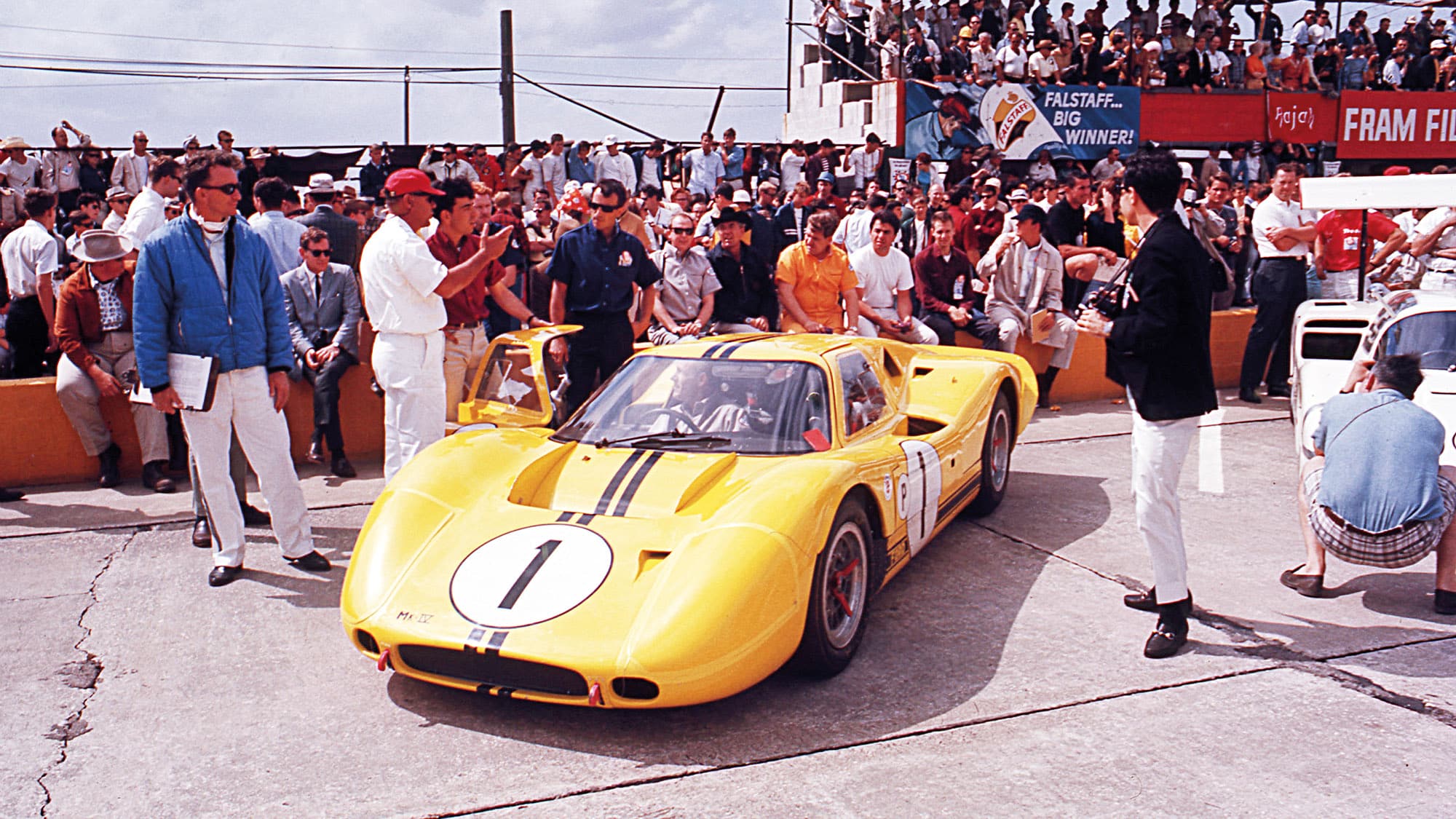

The first race for Ford’s GT Mk IV was the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1967, with Bruce McLaren, left, and Mario Andretti on driving duties

According to conventional wisdom, the Ford GT Mk II, popularly known as the GT40, is one of the most iconic road-racing prototypes in history, and for good reason. First, the Mk II finished 1-2-3 at Le Mans in 1966 – a feat recently brought to the world outside of motor sport in the 2019 film Ford v Ferrari. Then, a GT40 campaigned privately by John Wyer won the race in 1968 and 1969.

Still, it’s the Mk IV that deserves to be remembered as the ultimate all-American road-racing car. Unlike the GT40, it was designed, built and developed entirely in the United States, and it was driven to victory at Le Mans in 1967 by the most American pairing imaginable – Foyt and Dan Gurney. It’s one of the only cars to win a major event in its first race out of the box, and it retired as the undefeated, undisputed heavyweight champion of the endurance racing world.

“All seemed right in Ford World until the Ferrari 1-2-3 at Daytona”

Charlie Agapiou was the crew chief of the Mk II that controversially finished second at Le Mans in 1966. But he says the Mk II wasn’t in the same class as the Mk IV that replaced it. “That car was brilliant,” he says. “It gave us no aggro whatsoever.”

As most people know, Henry Ford II set the Le Mans programme in motion in 1963 after Enzo Ferrari rejected his attempt to buy the Italian carmaker. The original GT40 was an Anglo-American collaboration between Ford designers and engineers led by Roy Lunn and a British crew headed by Lola’s Eric Broadley (and the young Tony Southgate). The project was keenly observed by Wyer, who’d overseen the Aston Martin victory at Le Mans in 1959.

The Ford GT unveiled in 1964 was fast but fragile. In 1965 it was upgraded with a big-block 7-litre Ford V8 and dubbed the Mk II. The next year, the Mk II humiliated Ferrari. All seemed right in Ford World until the stunning new 330 P4 led a shocking 1-2-3 Ferrari sweep at Daytona at the start of the 1967 season. There was consternation at the Ford headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan. But out in Los Angeles, Phil Remington – Shelby American’s remarkable Mr Fixit – hatched a plan to make a silk purse out of the sow’s ear known as the J-Car.

Ford’s ugly duckling J-Car had an aluminium honeycomb chassis, which would be carried over into the redesigned Mk IV

GETTY IMAGES, REVS INSTITUTE

From the start of the Le Mans programme, Lunn had been worried that the Ford GT would be too heavy, so he began investigating weight-saving alternatives. Chuck Mountain, one of the three Ford engineers who’d worked with Lunn and Broadley in England, reasoned that a new car could be built out of a light but rigid honeycomb-aluminium material which had been developed by Brunswick, a company best known for manufacturing bowling balls and pool tables.

Legendarily hard-working engineer Ed Hull used this honeycomb-aluminium as the basis of a box-section chassis that he described as a “multicocque”. Riley says the ultra-stiff chassis proved to be an excellent platform for innovative suspension geometry optimised with a cutting-edge (by 1960s standards) main-frame computer. Ford Styling designed the J-car bodywork, which featured a lobster-claw front end and a long, flat, squared-off rear deck that inspired the not-very-complimentary nickname, the ‘Bread Van’. The car was built at Kar-Kraft, a motor sports skunkworks owned by Ford.

“It’s one of the only cars to win a major event in its first race”

The J-Car, as the Bread Van was officially known, actually turned the fastest lap of the Le Mans test in 1966, but Ford wisely chose to put its money on the race-proven Mk IIs. A month after Le Mans, Ken Miles was killed when the rear wheels of his J-Car locked up during testing at Riverside. The cause of the crash was never definitively determined, though most people attributed it to a brake issue or the failure of the experimental semiautomatic transmission.

Development of the J-Car ceased – until the debacle at Daytona the following February. With the Mk II outclassed by the Ferrari P4, Ford realised it had to pull a rabbit out of the hat. Remington was convinced that the only problem with the J-Car was that it was too “draggy”, as he put it. So he took the remaining chassis to the Ford wind tunnel in Dearborn and, working entirely by eye, started hacking away at the bodywork. Then, he said, “we built the thing up with plaster until it looked right”.

After a test showed the modified car to be faster than the Mk II, a new chassis designated as a Mk IV was laid down for the 12 Hours of Sebring. (The Mk III was a street version of the GT40.) Bruce McLaren stuck the car on pole, and he and Mario Andretti breezed to the chequered flag. Ford immediately commissioned four brand-new Mk IVs for Le Mans.

At Le Mans in 1967, GT Mk IV No2 was driven by Bruce McLaren and Mark Donohue and finished fourth, but the No1 of Gurney and Foyt, which carried a red livery (and in fact was parked next to No2 here, but is out of shot) made it two wins out of two for Ford’s unstoppable racer

Foyt savours the success

The MkIV was built with the specific purpose of Le Mans victory

The race shaped up as an epic showdown. Arrayed against the Mk IVs were three works Mk IIs, two high-wing Chaparral 2Fs, seven Ferrari P4 and P3 derivatives, three privateer GT40s, two lightweight GT40-based Mirages and a pair of sleek Lola T70s. McLaren qualified on the pole, three-tenths ahead of Phil Hill in the Chaparral, with two more Mk IVs third and fourth. But Gurney, who was usually the fastest of the Ford drivers, trailed back in ninth. Gurney said later that it was part of his grand plan. “The Mk IV was so comfortable that it was more like a passenger car than a race car,” he said in an interview before his death in 2018. “It had a big engine, ran at low revs, was very well balanced. I could go around corners just as fast as anybody, and on the straights it was so stable that I could have kicked back and smoked a pipe. But I didn’t know how it would hold up hour after hour in the race. So I decided to emulate Briggs Cunningham, who used to beat me every year [by driving conservatively]. The Ford guys kept saying, ‘What’s wrong with the car?’ I kept telling them, ‘Hey, the car is great.’”

History is made as American drivers in an American car take the chequered flag at Le Mans in 1967; to date, this is unique

But Phil Henny, who was one of three mechanics on the Gurney/Foyt crew, remembers it differently. He says Gurney was slow because he insisted on “fiddle-fuddling” – Carroll Shelby’s expression – with the car. “After qualifying, [team manager] Carroll Smith came to the garage and said, ‘You guys are not going to sleep tonight,’” Henny recalls. Instead, they transferred McLaren’s suspension settings over to Gurney’s car. “We worked until 5.30am.”

When the race began, Ronnie Bucknum led the first hour, driving hard in a Mk II. But once Gurney took the lead in the big red No1, he and Foyt never looked back even as all three of the other Mk IVs ran into trouble. They routinely clocked speeds greater than 210mph – nearly 20mph faster than the P4s – on the Mulsanne Straight while loping along at a leisurely 6200rpm.

“It was so stable that I could have kicked back and smoked a pipe”

Foyt confounded critics who thought the only thing he knew how to do was to turn left. “Foyt doesn’t make mistakes,” Denis Jenkinson reported in Motor Sport, and Henny says he lapped just as quickly as Gurney. Foyt suffered only one hiccup during the race, when he over-revved the engine to avoid sliding off the track after hitting oil at Maison Blanche. As for Gurney, the only pressure he felt came early Sunday morning, when Mike Parkes started tailgating him in his P4, flashing his lights.

“He wanted me to gas it, hoping that I’d break the car,” Gurney recalled. “I was so tempted to blow him off, but I knew what his mission was. This went on for at least three laps. Finally, I pulled over onto the grass at Arnage, and damned if he didn’t pull off right behind me! We sat there for maybe 15 or 20 seconds until he pulled back out. Four laps later, I caught and passed him.”

Gurney, right, was no stranger to Le Mans, having competed every year since 1958. A week after his Le Mans victory with Foyt he won the F1 Belgian Grand Prix

Gurney and Foyt won by four laps. According to legend, Gurney inaugurated a tradition by spraying champagne on the victory rostrum. Foyt, who’d won the Indy 500 two weeks earlier, was more restrained in his celebration. “Shucks. This wasn’t so tough. Indy was harder,” he declared afterwards. Or, as he used to tease his friend Bob Wollek, who never won Le Mans despite 30 attempts: “That’s the easiest damn race I ever won in my life.’”

Two days after Le Mans, the FIA effectively banned the Mk IV by placing a 3-litre limit on Group 6 prototypes. (Wyer cleverly homologated the small-block GT40 in Group 4, which allowed engines up to 5 litres.) A week later, Ford cancelled the Le Mans programme. Some desultory work was done to convert the Mk IV to an open-top Can-Am car, but this project was stillborn, and the cars were sold to Charlie and Kerry Agapiou (see previous page).

Four hours into Le Mans ’67 the MK IV passes a crashed Ferrari 365 P2 at Mulsanne

GETTY IMAGES, SHUTTERSTOCK

Kar-Kraft continued to work on other projects, including the Boss 302 and Trans-Am versions of the Mustang, until Ford abruptly closed the company. “The sheriff locked the doors, and the mechanics couldn’t even grab their toolboxes,” Riley recalls. Pretty much all documentation would have been lost if GT40 lover/Ford historian Mike Teske hadn’t been able to salvage filing cabinets – dozens of them, containing everything from photos and shipping details to engineering drawings and test postmortems – before they were thrown in the bin.

Teske and Kenny Thompson, a master craftsman who’d worked on the original Mk IV at Holman & Moody, later built seven magnificent continuation cars. Earlier this year, the Rileys partnered with Jim Matthews, a former team owner and gentleman driver who’d raced several Riley-built cars, to buy the Kar-Kraft assets, including tooling, fixtures and a collection of documents that Bob had generated back in the day.

The original drawings are now being digitised so that parts can be made using a computer-aided program. Many of the components used in the original Mk IVs were custom-made, so Bill Riley says finding vendors promises to be a challenge. Still, he hopes to complete the first car in less than two years. The anticipated price is £660,000.

Gurney and Foyt’s GT Mk IV dwarfs the Alpine A210 of Roger Delageneste and Jacques Chienisse

Heritage Images/Getty Images

Riley Technologies still runs a couple of LMP3 cars in IMSA as well as the Mercedes- Benz customer-racing programme in the US and supports two 488 EVO’s in the Ferrari Challenge series. The company also restores historic race cars, most notably the Riley & Scott Mk III that won Sebring and Daytona in 1996 and the gloriously unconventional front-engine Mustang GTP car raced in 1983 and 1984. But the Mk IV programme is a labour of love as much as it is a moneymaking proposition.

“I was always a Foyt kid growing up,” Bill says. “I was also a Ford kid. So the Mk IV is one of my favourite race cars of all time.”

And recreating it promises to be a father-and-son project for the ages.