Ford GT40: The spirit of Le Mans

Fifty years split the original Ford GT and the latest version, and both were created with one goal: to win the Le Mans 24 Hours. Andrew Frankel asks whether their shared history can bridge the passage of time

Jayson Fong

It seems strange that the latest Ford GT and the first Ford GT40 are separated by over half a century. Spool back another 50 years or so from the original car’s introduction and you end up at a Ford Motor Company in its infancy, a time when the Model T was just a glint in Henry Ford’s eye.

Today, the modern version has been retired from competition, while the original has become a favourite on the historic racing scene. And here the two Ford GTs sit. Two impossibly low, mid-engined, two-seat sports cars, their family resemblance clear. Unlike almost any other car you’d see on the road, or even in the supercar paddock at the Goodwood Festival of Speed, both the GT and GT40 were designed as racing cars first and adapted for road use second. Which, in the GT40’s case, could simply mean slapping a number plate on a racing car, which is what we have here.

“The big question is whether what they share in philosophy can bridge the 50-year age gap”

While both these new and old Fords raced all over the world, these cars were designed with one particular goal in mind: to win the Le Mans 24 Hours either outright, as was the case with the GT40, or by taking the GTE Pro class with the Ford GT. While it took the GT40 three attempts to duff up the Ferrari opposition in the 1960s and win Le Mans, the GT achieved its perhaps more modest goal first time out, on the 50th anniversary of the GT40’s original victory.

But the real question is whether what they share in their philosophy and reasons for being can bridge the half-century gap between them.

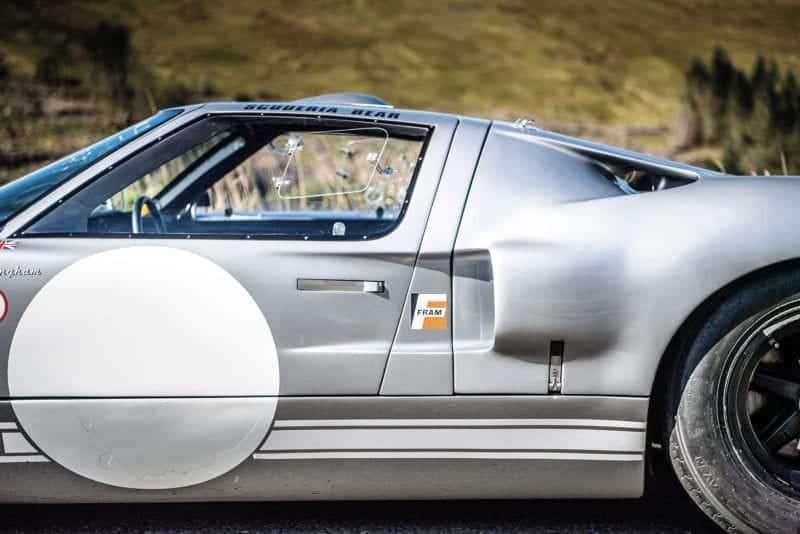

The GT40 seen here is one of over 100 GT40s built in the 1960s, the vast majority being sold, like this one here, to privateer teams. This GT40 was delivered to Scuderia Bear in the US in early 1966. The team was owned by one Bill McKelvy and got its name from the nickname he was called by his wife. The car’s first and last race was at Sebring that year where it finished 13th. It then went to Le Mans months later and was effectively destroyed when it was run into by the Alan Mann 7-litre GT40 MkII of Dick Thompson. Driver Richard Holquist escaped unhurt.

And that was that for chassis 1029. But the car’s identity lives on in this car, rebuilt using the original engine and gearbox around a repaired original GT40 tub, campaigned by owners and well-known historic racers Andrew Smith and James Cottingham. Since its rebirth at the start of this century, it has been raced successfully at the Le Mans Classic, the Goodwood Revival and elsewhere, including the two owners using it to take overall victory in the 2017 Tour Auto. The new GT also belongs to Cottingham and Smith and is, I’m told, one of 11 such cars to be sold new in the UK.

Blend of old and new: the original GT40 tub went through a loving restoration

Jayson Fong

We thought long and hard about doing this story on a race track, but given that both are road-legal, and that the road-going component is such an important part of their tales, we chose a quiet Welsh mountain road where we could see what these two Ford GTs have in common and what, despite it all, still sets them apart.

I took the new car first. I’m not sure why, but it seemed likely to require less learning. I’d driven it before but mainly on a track in Utah, and only briefly on a local road that looked nothing like the Brecon Beacons. Still, I thought I knew what to expect.

The MkI has nods to its past with Scuderia Bear, but is road-legal for its head-to-head with the GT

Jayson Fong

In some regards, the car’s racing heritage is both unavoidable and intrusive. Drive a European supercar of comparable performance like a McLaren 720S or Ferrari F8 Tributo and you drive a car that will accommodate not only you but quite a lot of luggage. In the Ford GT, it’s telescopic toothbrushes or travel solo and strap your Samsonite to the passenger seat.

More fundamentally, there’s the engine. Yes, it has 647bhp, which is very impressive, but the noise of the twin-turbo V6 is not. It may have been perfect in its compact dimensions and suitability to the racing regs, but as a road car it suffers by comparison to its 2005 predecessor, designed very much as a road car – though some did race. It may have had ‘only’ 550bhp, but that came from a supercharged 5.4-litre V8, which was perhaps more in line with the GT40 spirit.

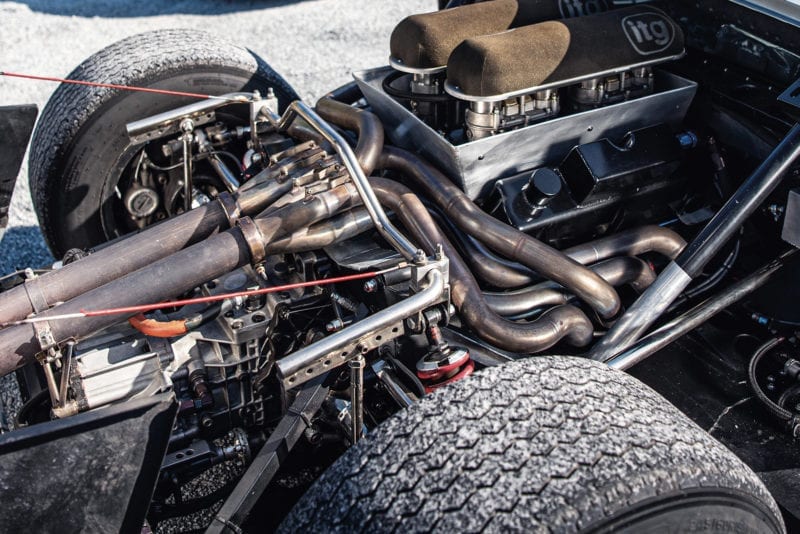

The Ford GT40 was famed for its V8 engine, although the modern car now uses a turbo V6

Jayson Fong

The small but powerful turbo motor is surprisingly quiet and dispenses its power in a commendably linear fashion through a similarly slick double-clutch gearbox. But the truth is that a power train is a tool for doing a job, be that hurling me across the Beacons, or winning its class at Le Mans, and that’s before you start to consider the rather more characterful (and powerful) V8s wielded by European opposition.

But there is one benefit to this car being conceived as a racing car first and a road car a very distant second. Its handling is astonishing. So much so that you can only learn so much on even a fast road across the Beacons. Driven as fast as is prudent, it’s the accuracy you appreciate most. It’s tempting to liken it to something very light for its millimetric precision, but it’s even better than an Ariel Atom or a Caterham, because weighing twice as much it’s not deflected by bumps or surface changes. You don’t have to work so hard. Yet you are aware of all the ability you’re not using. Grip levels are otherworldly – you’d have to be some kind of lunatic to unstick it in the dry. Aim it where you want it to go and that’s exactly where it goes, instantly and without deviation.

“In some regards, the new Ford’s racing heritage is unavoidable and intrusive”

On the track, where I have also driven a version of this car, you’ll find grip and composure that elevates it above even the McLaren and Ferrari rivals. I can remember five-time IndyCar champion Scott Dixon telling me the potential of the race version was so great that were the cars allowed to run outside the rules, its competition would barely see which way it went. Of course, Ford has done this before. The original GT40 had its road-going sibling in the form of the MkIII. This came with elongated bodywork to provide some luggage space, softer suspension, a detuned V8 and a gearshift relocated to the centre of the car. I only drove one once (which was lucky, given just seven were built) and it was not difficult to see why in period the press was less than impressed. I wasn’t that bothered by the relative lack of performance because it still felt quite quick to me, but the linkage required for the new gearlever position made the shift quality horrid and its handling was ruined by skinny 1960 street tyres and soft suspension. Combined with its exorbitant price (it was more expensive when new than the race car upon which it was based) and I had no trouble figuring out why it bombed.

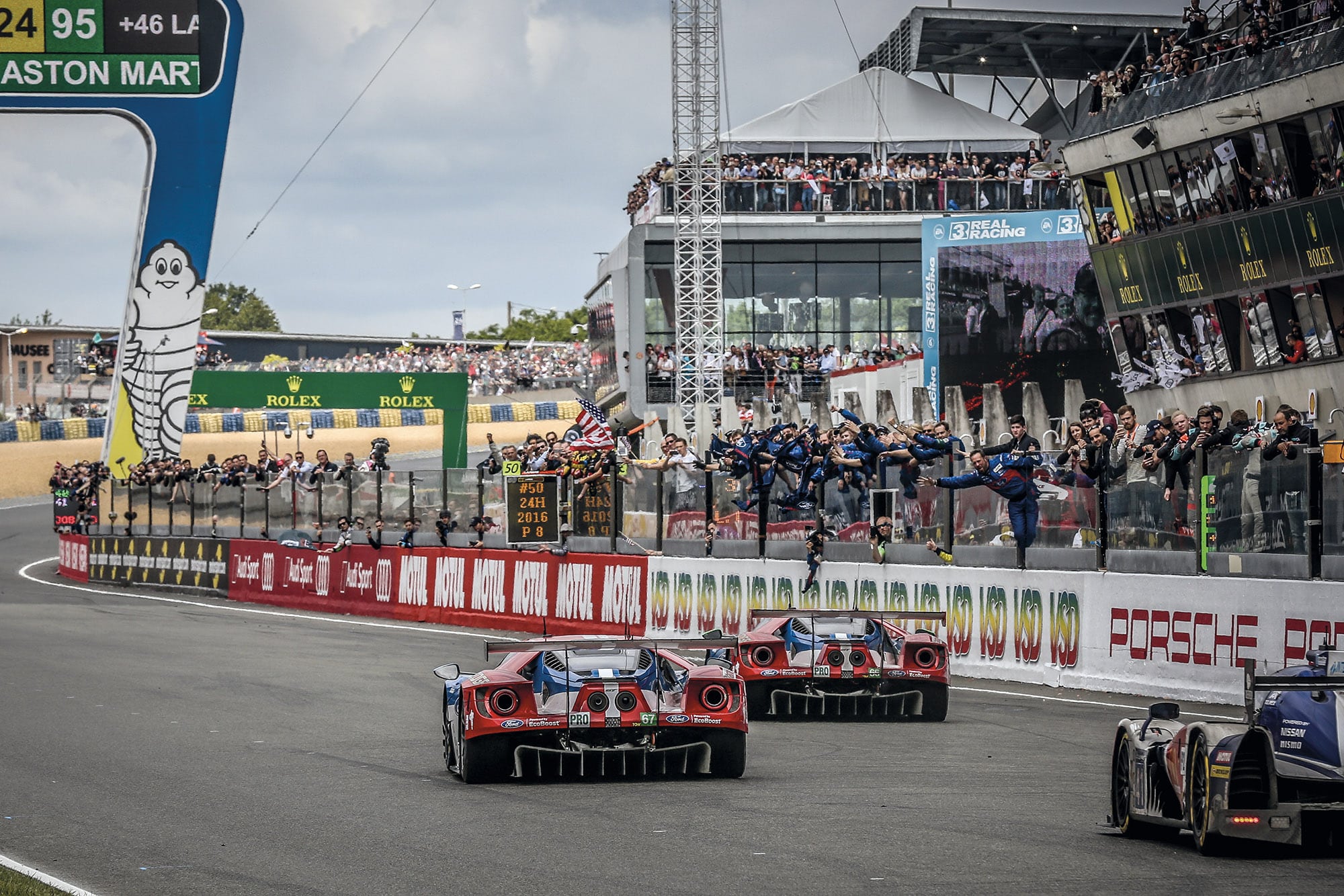

Touching distance: the final lap of Le Mans ʼ66, moments before Ford made history with victory

Getty

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

Chassis number 1029 lives again and proves more than a match for its modern counterpart

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

But what about that race car? It’s been a while. But at least I know I’ll fit. I don’t have to wear a helmet – this car has a Gurney bubble and the seat has been built to accommodate owner Smith, who is the same height as me. Climbing in is easy too, thanks to the door removing half the roof when it opens. So, you just drop down and survey the splat of switches and Smiths instruments in front of you.

The engine is a Steve Warrior full-race motor which means over 460bhp. Yes, that’s nearly 200 fewer than the modern GT and its 1100kg weight was heavy by 1960 Le Mans standards. But compare it to the modern Ford GT and the power to weight ratio of the 1960s racing car and the 54 years younger road car are near identical.

“Ford has done this before. The original GT40 had its road-going sibling in the form of the MkIII.”

The motor is so loud your first instinct is to laugh, but after one quick run up the road, I’m already searching the depths of my travel bag in the forlorn hope of finding spare earplugs. Still, as sounds to which to go deaf, few could be better than this. It’s the sound of America, turned up louder than Spinal Tap would dare. It snarls under power, spits on the overrun and to the uninitiated might seem somewhat terrifying.

Can you teach an old dog new tricks? Our road testers ponder the question in Wales

Jayson Fong

But GT40s were generally much liked by those who drove them in period and they remain so today, if the ever-increasing number of them at major historic race meetings is any guide. Imagine for a moment that you’re a wealthy privateer enthusiast: one year you’re campaigning your lovely lightweight E-type, then next you’re in a GT40 and going damn near as fast as factory works prototypes.

And they were also liked because they were, at least by the woeful standards of the day, pretty safe. People often talk about the Lotus 25 introducing monocoque construction to Formula 1 in 1962, but not many mention the Lola Mk6 GT was also built the same way in the same year, and it was Lola’s design that begat the GT40. Besides, it was fairly robustly constructed anyway, which made it heavy and had Ford wanting to shave over 100kg for its ill-fated J-car successor that killed Ken Miles. Should something have gone wrong in the middle of the night at Le Mans, it gave you more of a chance than a conventional car built around a flimsy spaceframe.

You sit amazingly low in the car, very reclined but with that lovely Ford steering wheel a perfect distance away. Visibility is surprisingly good, which is more important than usual today given the number of times I will need to turn the car around in laybys, access lanes and farm tracks to run past the camera again.

It’s not a difficult car to drive either. The clutch is comically heavy, but it takes up the slack gently. And the ZF five-speed gearbox with its right-hand shifter is easy enough. It’s quite slow by race car standards, but its synchromesh would have kept plenty of amateur race drivers pounding around Le Mans long after they’d have taken the edges off a conventional racing dog box. Porsche had the same idea for cars such as the 917 and 956.

But what you notice most, at least once your ears have become numbed to the racket from that engine, is just how small the car is. It feels tiny compared to its modern equivalent and indeed it is – it’s 226mm narrower, 698mm shorter, 81mm lower and its front and rear wheels are 297mm closer together – making it far easier to thread along mountain roads at speed.

Chassis 1029 raced at the 1966 Sebring 12 Hours with the Scuderia Bear team

Jayson Fong

And somehow it feels faster too, whatever the figures say. With no turbo lag, and utterly explosive acceleration never more than a twitch of a toe away, regardless of gear, it feels like it’s never going to stop. With this engine on board, I doubt it would until you were at least the far side of 100mph.

Switching from old to new provides totally different experiences behind the wheel

Jayson Fong

What it lacks is the composure of the GT. While the modern Ford flows unflappably from one point to the next, you simply cannot expect that level of accuracy from a car based on a 55-year-old design. It’s not in any way vague, but it requires a firm hand and a driver who understands that his input may not be matched exactly by the output at the wheels. Quite often you need to make minor corrections to hit your marks – and, of course, that’s all part of the fun.

“It’s the sound of America, turned up louder than Spinal Tap would dare”

Ultimately it will still look after you because it’s exceptionally well damped, probably rather more controlled than it would have been in the mid-1960s. Also, you’re not going to go fast enough on a dry public road to suddenly find yourself inadvertently over the limit. Or at least I’m not. But it keeps you busy and the reward is just about the most lucid steering feel I’ve felt in any car that was wearing a number plate.

Scuderia Bear’s MkI was destroyed at Le Mans after just one previous race outing

Motorsport Images

Should a comparison like this even name a winner? John Surtees maintained you cannot compare drivers from one era to the next because their equipment was so different and so I think it is with cars. I find that what they share – their steadfast focus on winning the world’s greatest endurance race – far more interesting than any of the things that time and technology has put between them. But if you asked me which I’d choose to take home for a day, a week, or the rest of my life, it would simply have to be the GT40 by a mile.

2020 FORD GT SPECS

Engine: EcoBoost 3.5-litre twin-turbocharged V6

Power: 647bhp

Weight: 1385kg

0-60mph: 3sec

Top speed: 216mph

FORD GT40 MKI SPECS

Engine: 4.7-litre V8

Power: 385bhp (approx)

Weight: 1000kg excluding driver

0-60mph: Estimated 5sec

Top speed: 173mph

Triumphant comeback

Ford’s Le Mans return was nostalgic, and it marked it with victory against an old foe

The romanticism of Ford at the Le Mans 24 Hours may have been revived on the big screen last year, but it wasn’t lost on the manufacturer back in 2016 either.

When Ford announced its Le Mans return, the links to the past were established, with the launch coinciding with the 50th anniversary of Ford’s Ferrari-beating victory.

Victory sparked renewed focus on GTE, with rivals scrambling to catch up

Drew Gibson

That nostalgia increased when the four cars for Le Mans 2016 were numbered 66, 67, 68 and 69, reflecting the four consecutive years Ford won Le Mans with the MkII, the MkIV and the GT40.

And the World Endurance Championship could hardly have written a better script for the 2016 race, as Ferrari and Ford went head-to-head once again.

Porsche initially took the early class lead, before Ford moved clear and looked to be in control when both of the AF Corse-run Ferrari 488s hit trouble. Then the Risi Competizione 488 joined a three-way fight with the no68 and no69 Fords.

By dawn, the Risi Ferrari had gained a lead through quicker pitstops, only for a duel in the final few hours to go to the no68 Ford driven by Joey Hand, Dirk Müller and Sébastien Bourdais, securing a famous win.

But with Ford now ending its factory backed presence, run with Chip Ganassi Racing and Multimatic, attention turns to its legacy.

Yes, there was the symmetry of winning on the anniversary of its first Le Mans win, but it also helped redefine the GTE Pro class. Ford designed the race car first, road car second, and led its rivals, such as Porsche and Aston, to refocus and bring new iterations to fight back.

It may now be gone, but Ford played an important role in what’s seen as a golden era of GT racing while WEC steers through an unclear future with its top-tier class.