The lost gamble

A Team Lotus Formula Junior car has resurfaced after more than half a century tucked away in a Turinese workshop following an infamous bet. The intriguing car will soon return to action, as Simon Arron explains

Jonathan Fleetwood

It’s hard to imagine a comparable situation in the modern era. Were it to arise, the most likely outcome would be lawyers insulating their bank accounts with another dense layer of notes, but that’s not always how the world worked in 1962. When prominent German writer Richard von Frankenberg used his Auto Motor und Sport column to outline suspicions about the engines the factory Lotus 22s had been using during its successful Formula Junior campaign – notably during a race at the Nürburgring – team boss Colin Chapman responded not with litigation, but with a bet. He agreed to take the car you see here to a venue of his accuser’s choice, repeat the race-winning speeds of earlier in the season and then have the car stripped for technical inspection. If he was vindicated, he’d collect £1000 and von Frankenberg would retract his allegations.

Andrew Hibberd wants to faithfully restore the Lotus as if it had just dropped out of its ’60s heyday

Jonathan Fleetwood

As editor Bill Boddy predicted – correctly – in a Motor Sport editorial (December 1962): “It is not known definitely at the time of writing whether von Frankenberg will choose Monza or the Nürburgring for the test, but probably he will insist on the former where car rather than driver determines lap speeds.” Before the Monza run on December 2, von Frankenberg – who claimed to have proof that Lotus had used oversized 1450cc engines – called the situation “the greatest disgrace in international motor sport”, to which Lotus responded: “The greatest disgrace in international motor sport is that this libellous attack should ever have been published.” Boddy added: “We await with interest complete vindication of the British flag, the Germans having proclaimed that ‘it will take a long time to overcome the lack of confidence in the English’.”

“I was struggling to sleep one night and spotted it on Instagram”

Lotus went to Monza with star driver Peter Arundell, winner of that season’s European and BARC Express & Star championship titles as well as the Monaco Grand Prix support race. It took along this chassis, 22/J3, with which his team-mate Bob Anderson had been a front-runner throughout the season (Anderson had finished third in Monaco, the two Team Lotus cars separated by the similar Ian Walker Racing 22 of Mike Spence). Conditions at Monza weren’t quite comparable with those at June’s Lotteria meeting, where Arundell had won both his 15-lap heat and the 30-lap final. It was cooler, and there was no traffic with which to contend – but there was no doubt about the result. The official Lotus press statement read: “Peter Arundell, driving his Team Lotus Formula Junior, won the Monza Challenge by averaging 115.3mph for the 30-lap test. In recording this average speed, which was 52sec quicker than the time for the Monza Lotteria Formula Junior race in June, Arundell unofficially broke his own Formula Junior circuit record by recording the fastest lap of 1min 49.8sec.”

Checks by German and Italian officials confirmed that the car complied fully with the regulations. The engine capacity was found to be 1092cc, 6cc below the legal limit, and Lotus signed off: “The results should effectively disprove all von Frankenberg’s theories on oversized engines in Team Lotus Formula Junior cars during the 1962 season.” Boddy concluded with a right jab of his own: “Richard von Frankenberg was indeed foolish, for has Colin Chapman ever been known to indulge in sharp practice?”

It was to be a doubly fruitful trip for Chapman. Not only did he win his bet that afternoon, but he found a buyer for the 22 and, as far as can be ascertained, it remained in Italy. Relatively little is known about what happened to it in the showdown’s immediate slipstream, but a few gaps were plugged more than half a century later, thanks to a restless night and social media…

Jonathan Fleetwood

Jonathan Fleetwood

Lotus 22. Formula Junior, Goodwood, England, August 1962.

Sutton

The marks that helped prove the Lotus’s authenticity

Jonathan Fleetwood

Jonathan Fleetwood

Jonathan Fleetwood

The Lotus 22 proved popular in period, here racing in the 1963 US Grand Prix

Motorsport Images

Hibberd was surprised by the sheer quantity of original parts on the Lotus

Jonathan Fleetwood

In recent times, Andrew Hibberd has been one of the UK’s most prominent performers in historic single-seater racing, a serial front-runner – and regular winner – in both Formula Junior (at the wheel of a Lotus 22 that was based in Denmark in period) and Formula 3, in a Brabham BT18A. He now owns chassis 22/J3 and is preparing it for the season ahead. It is scheduled to commence its comeback tour at the Goodwood Members’ Meeting at the end of March, driven by Andrew’s father Michael.

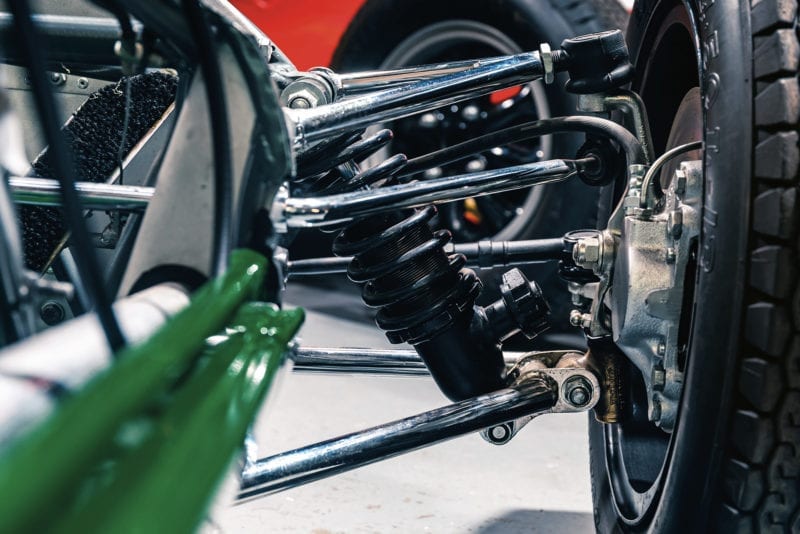

“I found the car completely by chance,” Hibberd Jr says. “I was struggling to sleep one night, picked up my phone at about 3am on a Sunday, and spotted it on Instagram. I do a lot of Lotus 22 hashtags and received this algorithm advertisement for what was said to be a 1961 Lotus FJ, ex-Peter Arundell. I had a closer look and could see it was a 1962 car, then became curious as it had lots of original parts. For a long time, lots of people have been racing 22s in Junior with a 1964 F3 tail section – nobody really knows why, but it has come to be accepted. I could see that this car had an original tail and non-adjustable top-link suspension, which isn’t uncommon, but nobody runs it today in historic racing. It had all the period Armstrong dampers, which I could recognise as old. The more I looked, the nicer the stuff I found – but all I knew was that it was located in Italy, and that Arundell had driven it.

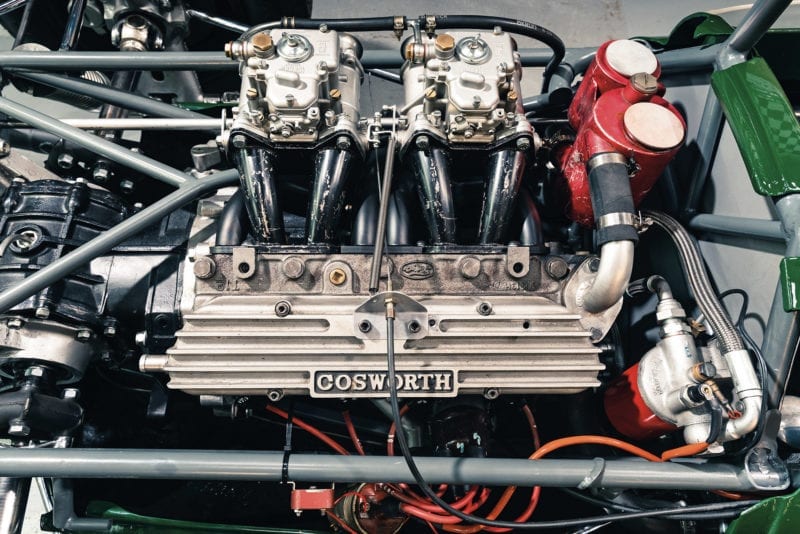

Bare bones: once on display in a Milanese hair salon, chassis 22/J3 is being prepared for a racing return and features original steering wheel, radiator, oil tank, brake pedal and Cosworth MAE engine

Jonathan Fleetwood

“I was sceptical at first, because I get quite excited by this kind of thing and didn’t want to rush into it but, at the same time, I didn’t want to let it slip through my fingers if it was something interesting. I went to do some homework, checked all my reference books and looked through all sorts of things. When I first phoned about it, the vendor spoke about as much English as I do Italian, so I got an Italian friend to call and then spoke to Junior guru Duncan Rabagliati. After going through his records, we established that it might well be 22/J3, so I set off to see it in our 22-year-old Ford Transit – a Junior fits neatly in the back.”

It transpired the car had for a while during the early 1960s been displayed in a Milanese hairdressing salon, where it remained until it was acquired in 1967 by the partners in a Turin-based automotive repair and servicing business. Lack of time forced them to reconsider racing, and it was tucked away in a corner of the workshop, under a tarpaulin, where it remained until being exhumed for sale late last year.

Hibberd has restored several Lotus 22s, but wants this one to have a battle-worn feel

Jonathan Fleetwood

“I’d looked at an Italian magazine feature which covered the 1962 Monza test extensively,” Hibberd says, “and had noticed a few distinguishing marks. That car had an oil filter in a very unusual place for a Lotus 22 – behind the roll hoop when normally they are mounted on the front of the chassis behind the oil tank. This car had that. The same photo showed J3 also had a big dent in the swirl pot, for some reason, and that was also present. It was all in pretty good nick given how long it had just been sitting there. There were lots of Lotus part numbers etched into things, so we knew it was genuine. I didn’t like the way somebody had modified the throttle pedal and thought that was a bit of a shame… until I found pictures that showed it was like that in 1962. It had ‘BA’ engraved on each of the wheel rims too, for ‘Bob Anderson’. Everything pointed to this being the real thing.”

Deal done, Hibberd waited in Italy for two days while funds cleared – “I spent most of my time in a local IKEA because it was warm, parking was free, and I needed a few things” – before loading the 22 into the trusty Transit for the first chapter in its second career. That was on November 28, 57 years to the day since Team Lotus had left the UK to prove the car’s legitimacy at Monza.

“The car had for a while been displayed in a hairdressing salon”

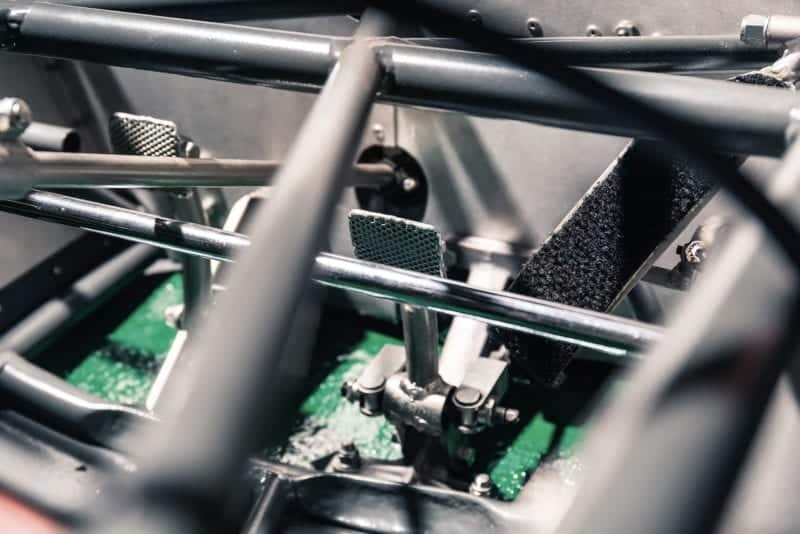

“So many bits are completely original,” he says. “Steering wheel, mirrors, screen, all four corners bar the front calipers, radiator, oil tank, brake pedal, its Cosworth MAE motor… It was in running condition when we brought it back, but we knew we’d have to take it apart to do a few checks. We’ll also fit new wishbones and bodywork because the intention is to race it properly and it would be a shame to risk damaging the originals. There are a few modernising touches that have to be made, to meet safety legislation – fitting belts, for instance. Oil and water originally ran through the chassis, but now we have to run them through separate aluminium pipes that I will paint to match the chassis, to camouflage them. It needs a fire extinguisher, too, which I’ll try to conceal as best I can, plus master switches and stuff, but some of that can be hidden quite nicely.

“I want to do it sympathetically. I have restored six or seven 22s and they usually emerge bright and shiny, but that’s not the intention this time. I want it to look as though it has fallen straight out of 1962.”

Anderson’s best F1 result: third in 1964’s Austrian GP

LAT

A precious connection

Son of Anderson’s bid to uncover his father’s legacy

Lotus 22/J3’s regular driver Bob Anderson was a successful motorcycle racing privateer who showed parallel aptitude when he switched to cars.

Notably second to John Surtees in the 1958 Isle of Man Senior TT, Anderson stepped away from motorcycles at the end of 1960 and took up Formula Junior, driving a Lotus 20 during 1961 before joining Team Lotus alongside Peter Arundell and Alan Rees in 1962. He raced in Formula 1 as an independent, under the DW Racing banner (the name a tribute to Allen Dudley-Ward, who worked on Anderson’s bikes).

After winning the 1963 non-championship Rome Grand Prix at Vallelunga, Anderson used a Brabham BT11 to score his best F1 world championship result, third in the 1964 Austrian Grand Prix at Zeltweg. He raced in further F1 races in a BT11 but died on August 14, 1967, due to injuries from a testing accident at Silverstone.

Bob Anderson

LAT

“I have very few memories of my dad,” says son, Bruce. “I was three when he was killed and my mother shielded me from the racing side of his past when I was younger. I became interested anyway so I guess it’s the Anderson DNA.

“I have been trying to gather photos, paperwork and other memorabilia from his career, to create a connection with the father I never really knew. I tried about 15 years ago to locate his 22. Classic Team Lotus had no idea where it was and nor did Duncan [Rabagliati], from the Formula Junior Historic Racing Association. If those guys didn’t know, what chance did I have? The fact it has finally resurfaced is both a surprise and a delight.”