Letters: October 2017

Alfas still going strong I write to ask you to correct an inaccuracy in your otherwise excellent Pescara report, which gave great prominence to the magnificent Alfa Romeo RL Targa…

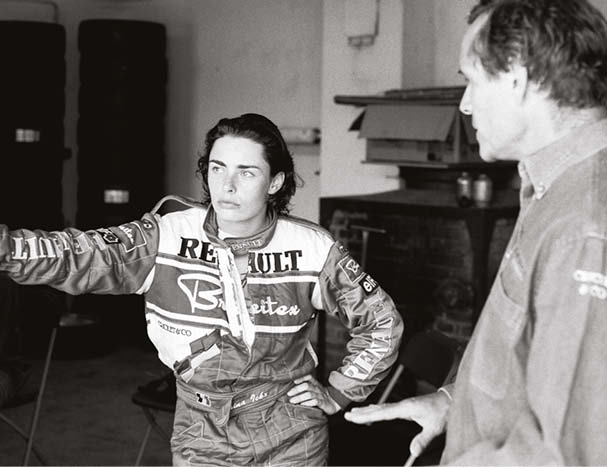

Jacky Ickx enjoyed huge success in multiple motor sport disciplines and had long since retired when daughter Vanina made her own way in the sport and followed in her illustrious father’s wheeltracks by racing at the Le Mans 24 Hours.

Jacky, 74, won Le Mans six times across three decades — with Ford, Mirage and Porsche — and also took eight grand prix wins driving for Ferrari and Brabham, finishing second in the drivers’ world championship in 1969 and 1970.

Vanina, 43, didn’t start racing until she was 21 and went on to race at Le Mans seven times with a best result of seventh.

Vanina: We didn’t see dad a lot when we were growing up. But when we did, it was the best of times.

Compared to a working father, who’d be leaving and coming home when the kids are in bed, dad would drop us at school and pick us up again, which was lovely. And then there were the holidays…

He made us travel and discover things that few other fathers could have showed us. After falling in love with the places and people of Africa, during the Paris Dakar [which Ickx won in 1983], he hired a guide and cook, bundled us into his Mercedes and took us on an adventure of a lifetime.

We’d cook whatever we could find or buy along the way, the water was from wells, filtered through our T-shirts, and we’d just sleep under the stars. He wanted to give us a broad perspective of the world.

He was a private man, with just a few friends from motor racing, and even when famous people would visit they were simply family friends to him and to us. At home, his trophies and memorabilia would be in the garage, and he wouldn’t talk about races or wins. He just wanted to be a regular dad. I only really began to learn about him and his achievements when I was much older.

After my parents separated, and dad moved to Monaco, I didn’t go to see him. Mum and dad did a good job of sharing us. They would never have a bad word to say about one another; theirs was a relationship built on respect. Even to this day, he will spend Christmas with all the family.

I didn’t grow up with a dream of racing cars. I could never have imagined I’d race at Le Mans, for example. So I never felt like I was living in the shadow of dad.

He’d tell me, “Life is about choices. Anytime, anywhere, you’re making choices. You close doors and open doors, and can choose to be who you want to be.” It’s advice I will pass on to my children.

I don’t see myself as a role model. I just like to push the limits – mentally and physically. It’s what makes life interesting; learning new things, overcoming fears and getting better at what you are doing. So it makes me angry that motor sport isn’t doing enough to make itself accessible to women. There are initiatives, like the W Series, and the FIA’s Girls on Track, but we are way behind places like America. The organisers and sponsors could help stimulate this.

Personally, I would prefer to see women compete on equal terms with men. But if female-only series help bring more women to the sport, then that’s better than nothing.

But be in no doubt, racing is tough. You have to prove yourself strong, physically and mentally, and ultimately that was my downfall. I didn’t deliver at critical points in my career, and made mistakes at a level where you simply can’t afford to.

For example, I raced with dad at the 1998 Spa 24 Hours, [driving a Renault Mégane coupé for Renault Sport Belgium; car no 2 finished third] and crashed. And in 2010, racing the Lola-Aston Martin, after 20 hours we were running in eighth – and could have made fourth – but I crashed badly enough to damage the tub. It feels stupid to talk about it now, because what’s done is done and you can’t change it, but I could have done better.

It’s amazing my father came through his career safely. I read a book, À Bâtons Rompus, which was written by a friend of his in the early ’70s. It brought home the dangers for drivers in that era. And I think it’s why he was so nervous when we raced, as a family, in the VW Fun Cup [in 2017] during a 25-hour race at Spa. I think he knew he was lucky he’d made it through safely.

“To survive, you had to be lucky. Your guardian angel suffered a lot”

So it was fascinating to drive an old F2 Porsche 718 at the Monaco Historic Grand Prix, last year, during a parade. The car would have been in competition just before dad started racing. I expected it to feel very dated and have a gearchange like stirring mayonnaise with a stick. But actually it felt fantastic. It was quick, so light, no bodyroll.

I came out of retirement to race at the Pikes Peak Hillclimb. There is something so special about it, and the project with Gillet was exciting. It was to celebrate 25 years of the Vertigo car, and we started with a blank piece of paper – no car, no one to build it and no sponsors. But by the end of it we finished sixth in our class, which was incredibly satisfying. It’s a pure form of competition – no practice or warm-up – and there’s danger at every turn. Yet if I were asked to go back, I’d say yes in a heartbeat.

We have just embarked on a new adventure. After earning my pilot’s licence, last August, I decided to take the plunge with my husband, Benjamin de Broqueville, and buy into a private aerodrome, in Namur, an hour south of Brussels.

It’s a very modest set up. We have just the one full-time employee, and there are just a handful of tenants leasing the buildings dotted around. The first major improvement we have made is to install a new concrete runway in place of the old grass landing strip.

Benjamin’s grandfather, father and uncle were pilots, so you could say it’s in the blood. We have a dream to fly around the world in a light aircraft. You never know; the airport is going so smoothly – better than expected – that perhaps there’s still a way for us to make it happen…”

Jacky: “It was another planet when we were racing. And to survive, you had to be lucky; your guardian angel suffered a lot.

Looking back, my parents suffered a lot. Communication wasn’t what it is today, and I didn’t call them enough on race weekends, so sometimes they would have to wait to read about my races – and, to be brutally honest, find out whether I was still alive – in the newspapers or magazines.

I have a lot to thank my parents for. I was lazy at school and if my parents hadn’t bought me a 50cc trials bike, as an incentive to work harder at school, I would probably have gone on to be a gardener. For any parents now whose children want to get into motor racing, they have to be able to say, ‘You’re free to do it. It’s your life.’ That’s what I said to Vanina. They will leave the nest and fly by themselves, so your role is to take care of them when things don’t go well.

Having Vanina and our other children did not change me, mentally. She was late to racing. By the time she showed an interest, school was behind her and she’d completed a degree in biology. However, I had no desire to coach her or manage her; I was happy to offer her support as a father, but I had no desire to play a role in her motor racing career. She did it all on her own. Perhaps starting so late is a regret of hers. And maybe she would have wanted me to coach her from the early days, and get her into motor racing. But I never saw that as my role.

And in another way, just as the pain was there for my parents, so it was there for me. When your daughter or son is driving, you share in the unhappiness when it doesn’t go well, and the joy when it works. And for me, the satisfaction doesn’t balance the potential risks or make up for the tension you feel when your children are racing.

And that’s despite the improvements in the safety of the tracks and cars. When Vanina first raced at Le Mans, in a Chrysler Viper GTS-R, I was so nervous, but I hid it from her and everyone else. I come from an era where we lost great friends every year, and no matter how improved the safety is, there is always going to be a risk.

So she was alone in her career. I was not behind her at all, which is why I believe she has been very brave. She started late, did well and deserved more. Keeping my children grounded was always important to me. It’s why I took them to Africa, to see life on another continent and educate them on how people in other parts of the world live.

These days, not only do young drivers have to have the natural talent, they have to find themselves a driver coach, physical coach and mental coach and be bloody good at the commercial side. They have to be able to sell themselves, even when they haven’t achieved anything yet.

The sport has been transformed into a business. But regardless of whether you’re talking about now or then, there are many talented people behind the scenes who make it possible for a racing driver to be successful.

Think about it. My success in motor racing isn’t just down to me. There were many other instrumental people, including Ken Tyrrell, Enzo Ferrari, John Wyer, Jack Brabham and Carl Haas.

These days, you have to wonder about the long-term future of motor racing. What direction will it go in, given the impending evolution of the car? Will fans always want to follow someone racing in a car? Can the grandstands remain busy and will the show go on? If the show is good, then the fans will come, but I feel that motor racing doesn’t pay close enough attention to the fans. It needs to listen to them to survive.”

Interview by James Mills