THE PROS AND CONS

THE PROS AND CONS in With other series we've always said there are alternative routes a driver can take to the top. But it's hard to argue against doing F3.…

Mark Morris & Julius Kruta. Published by Porter Press International, £60. ISBN: 978-1-907085-48-2

There’s something to be said for a formula: you know what came before, and you can be confident about each new offering, and Porter Press has certainly maintained that confidence with each new work in its Great Cars series. Each book focuses on a single chassis, serving up its entire detailed history together with sidebars and sub-sections on the people involved, the builders, the buyers, the events they contested and the era when it all happened. In addition, the writers are recognised marque experts, so you can expect a repository of trustworthy information, much of which also of course applies to other chassis of the type. And for a standard rate of £60 per volume, you get an armful of facts and pictures.

A Bugatti has not so far featured in this series, so it’s unexpected that for number 13 Porter has opted not for a grand prix-winning Type 35B or a sublimely beautiful 59 with those radial-spoked piano-wire wheels, but for a Type 50. Not the first model the Molsheim marque conjures up, nor hugely successful, but I dare say they had their reasons. It was Bugatti’s first works Le Mans entry, for example. And being less known, there’s more for us non-specialists to learn about this big-engined behemoth that for a while led the French 24 Hour enduro – and was suddenly withdrawn.

Logically enough the book opens with a section entitled ‘Setting the scene’, including ‘The world in 1931’ – an ambitious target, but actually constructive because it points out that though Germany and Britain were feeling severe after-shocks from the Wall Street Crash, France was less affected. And yet though the sort of people who could buy Bugattis ought to be less bothered than the rest of the population, the firm’s sales began to slump. That didn’t stop Bugatti offering 10 different models through 1931, including its new 4.9-litre tourer, the 50.

“Despite a short stint in the lead, a series of tyre ruptures prompted the team to withdraw”

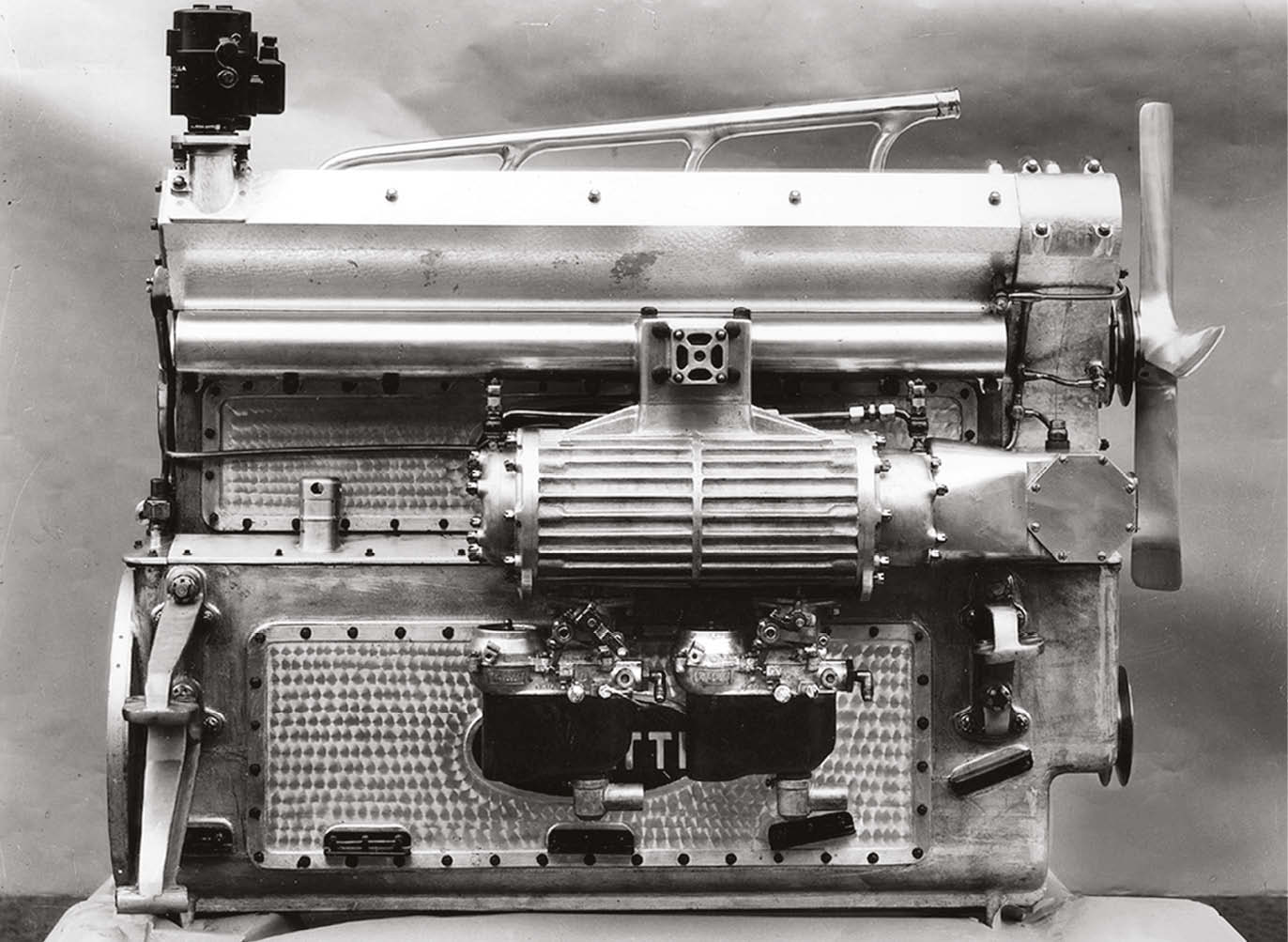

Much of the 50 derived from the Type 46 ‘Petite Royale’, a grand saloon which only looks ‘petite’ in relation to the vast Royale itself. (Collector Sam Clutton once gave me a lift in his 46 and casually said “why don’t you drive?”. I still regret that I declined due to cowardice.) Carryovers included torque tube, transaxle gearbox and alloy wheels but the giant leap was to employ twin camshafts for the first time. On the constant question of how much Bugatti borrowed from the pair of twin-cam Millers it purchased in 1929, the book quotes Ettore’s son Roland saying, “We learned a lot from it but it was impossible to use much of it…”

Nevertheless the 4.9-litre T50 had bevel-driven cams and a supercharger, producing up to 250bhp. Yet this was no racer but a heavyweight sports touring car, so it is surprising that, pushed by Jean, Ettore sanctioned racers for the Mille Miglia and Le Mans. On the other hand, lined up for the 1931 race in a fine double-page image here, the T50s match the Bentleys and SSK Mercedes for bulk, and suddenly it makes a lot more sense. Sadly, despite a short stint in the lead of that first race, a series of tyre ruptures prompted the team to withdraw the leading car, a frustrating high point for the project. With a chapter on each of the four race years, the book continues with its blizzard of facts and illustrations – there are two or three on every page, a mixture of photos and reprints of adverts, letters, drawings and factory records which confirm the immense research behind the project, though the general reader may skim over the runs of chassis numbers and the five pages of Le Mans regulations.

None of those Le Mans entries was successful as we know, but the chassis in question, 50177, contested three of them and has had a continuously recorded history since, carefully reported here including its purchase by Luigi Chinetti and export to the US, and its more recent return to Europe. Driver recollections from Le Mans and extensive correspondence with the mechanics for these races helps bring comprehensive and first-hand colour to its story, while the other Le Mans Type 50s also get their moment in the sun.

As well as reprinting various articles, there are driving impressions and a recent ‘Portrait of 50177’, though the quality of these is gloomy compared with the otherwise high-quality presentation, especially of the early glass-plate images. I’m not convinced the full biographies of all drivers are vital to this sort of book, nor the spread on a factory that pressed the T50’s outsourced chassis members. The latter is the sort of detail that excites the historian on the hunt but doesn’t necessarily grab the reader. On the other hand, at only £60 for a weighty 320 pages, one shouldn’t carp over too much content, especially as there is plenty here to learn.

For instance, there was a plan to enter a streamlined T50 coupé in the 1936 LM event, and factory drawings of the unbuilt design also show trailing-arm independent front suspension reminiscent of the later 2CV, though leaf-sprung. Presumably it was a small shot in the battle Jean B would never win against his father over that elegant but desperately old-fashioned front axle. Another revealing detail mentioned is an exchange between father and son after Ettore criticises the T50. Jean replies with a robust attack on the T46’s faults, to which Ettore writes “you know all the weak points of our junk…” Bugattis are junk – official.

The authors are not afraid to put others straight, even respected Bugatti historian Hugh Conway, but as Morris is registrar of the BOC while Kruta was for 15 years modern Bugatti’s head of tradition, I assume we can take their word. Another impressive production, then, on one of Molsheim’s less famous sons.