Fire up the Quattro: Cosworth’s unraced 4WD F1 design

Cosworth's 4wd thinking was reasonable, but aerodynamic technology overtook it before it could be developed

Grand Prix Photo

Cosworth’s nascent 4WD F1 design featured a host of innovative engineering concepts, even if not all of them worked as intended. Here’s a look under the skin of the machine, with some input from Peter Connew – of Connew Grand Prix fame – from our ‘I wish I’d Designed’ series of features from the early 2000s

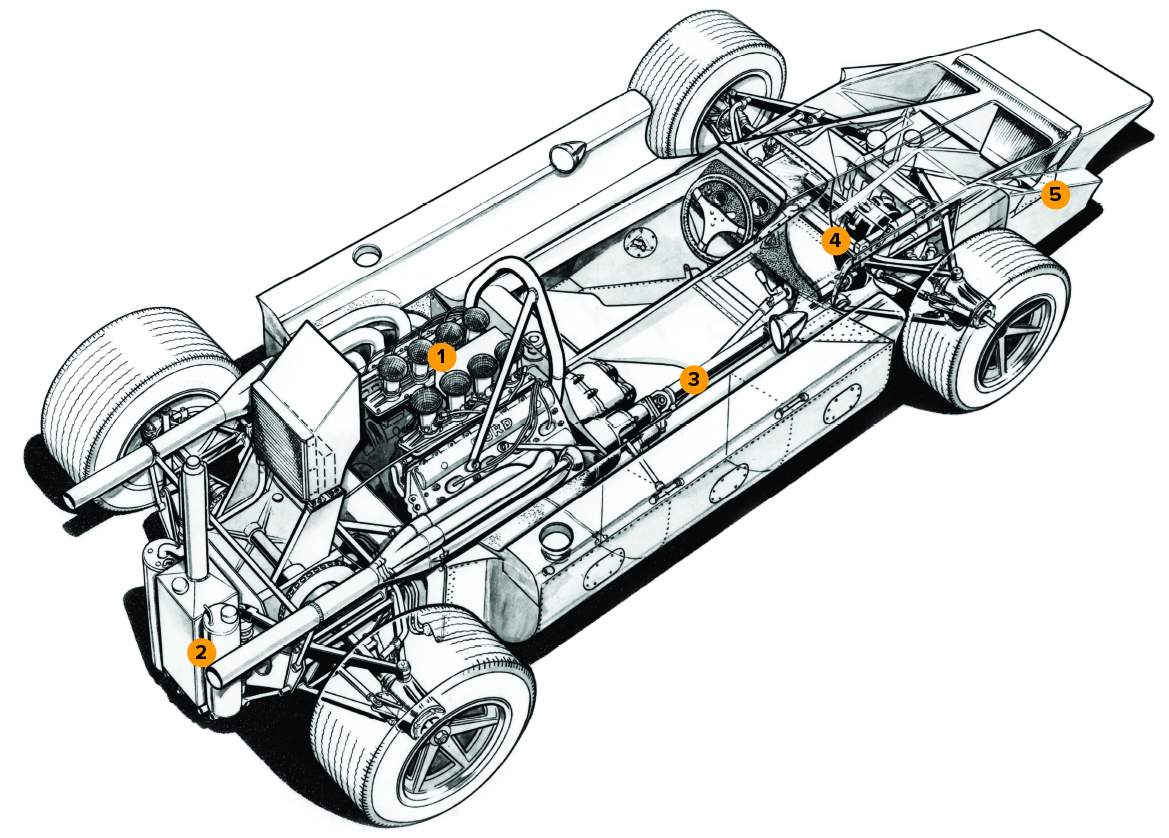

1: Engine

The 3-litre Cosworth DFV engine was well established in F1, but the version in the 4WD was markedly different. It remains the only DFV to have been made with a magnesium block in an attempt to recover some weight and compensate for the extra running gear. Connew called the cast-magnesium block “a potential development nightmare”

2: Rear End

The gearbox was moved in front of the DFV, and the engine oil tank formed the rear. The rear also supported a small rear wing when Cosworth experimented with aero

3: Drivetrain

Knowing that transmitting the drive around the car would be a challenge, Cosworth mounted the DFV backwards, so the clutch was immediately behind the driver. This let the engine drive the rear via a short driveshaft and then send up to 430bhp to the front axle via a collection of differentials and driveshafts, which were fed down the chassis by the driver’s right-hand side.

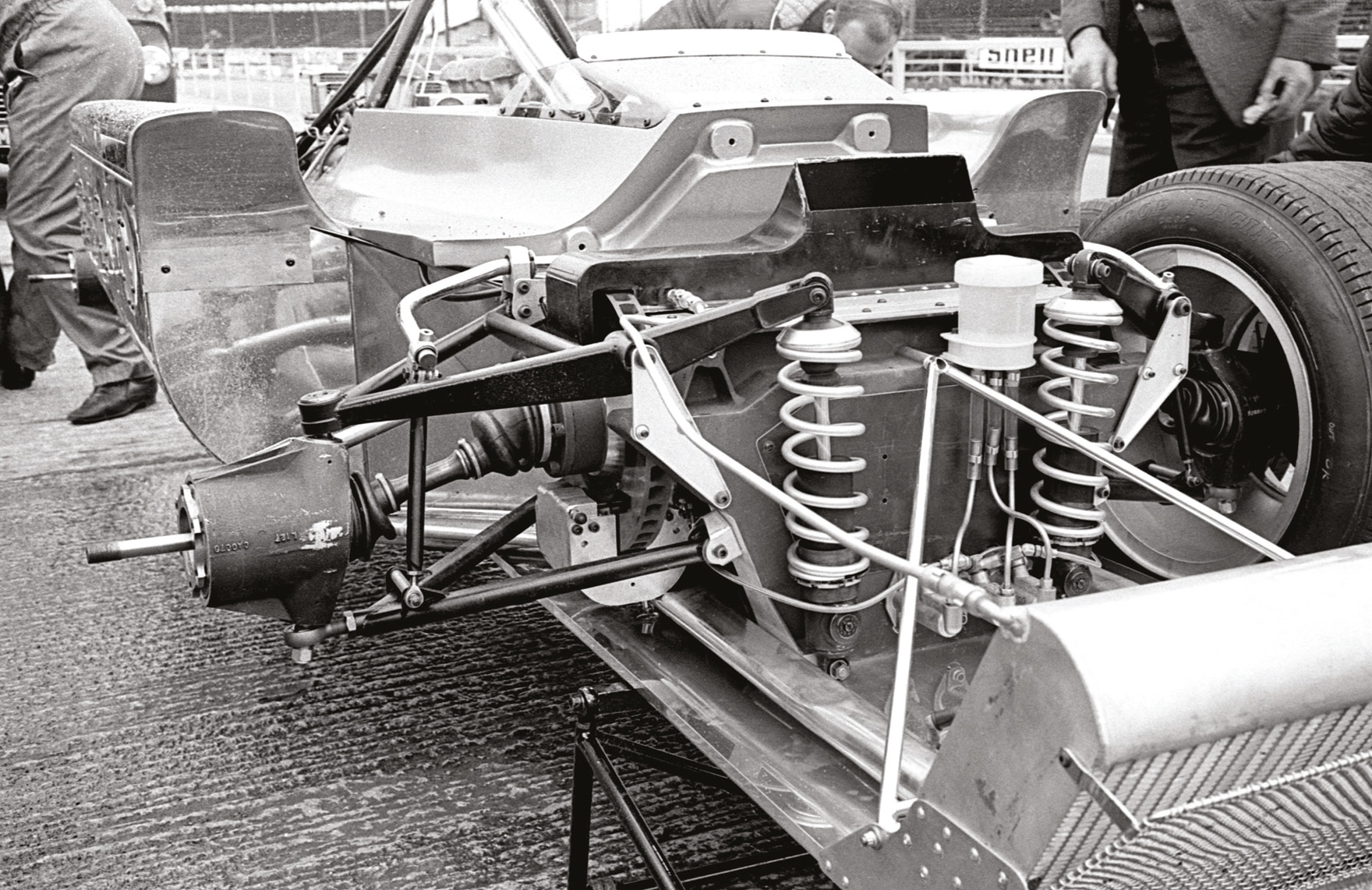

4: Front end

The front end used some very different technology. Connew: “The front bulkhead was double-skinned, effectively forming a box in which the front differential was housed. On paper, it was a purist’s dream: same suspension geometry front and rear; same tyre sizes front and rear; a 50:50 weight split. The problem was imbalanced traction through the front wheels. This was probably due to the limited-slip action of the front differential. Today’s technology would have helped. An LSD using a modern viscous coupling can be tuned to give a very predictable shearing performance. They have been developed and perfected to the point where a wide range of control is possible. This car was helped when the differential was altered so it didn’t work on the throttle overrun”

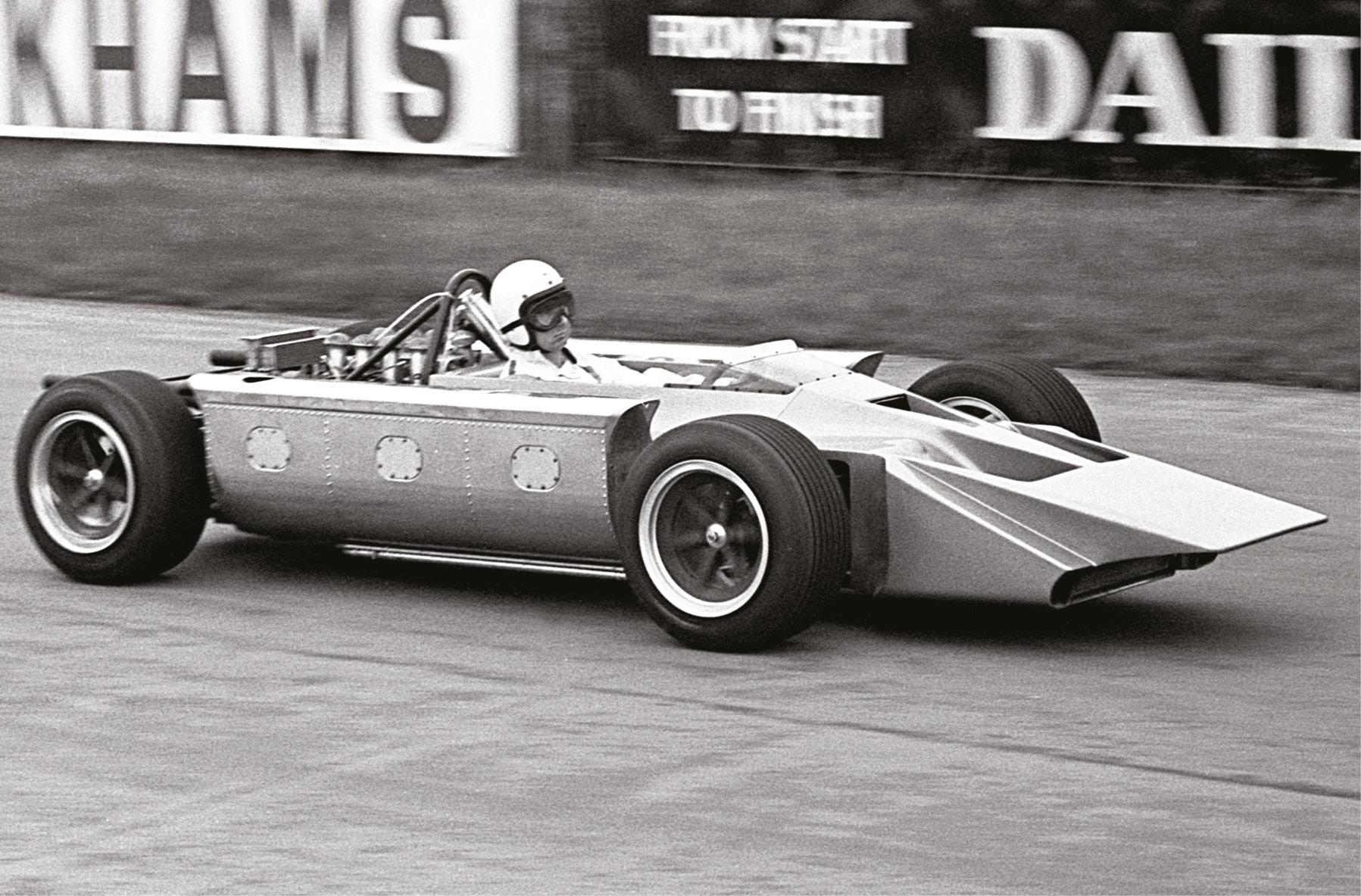

5: Aerodynamics

The 4WD’s bodywork was fashioned from sheet aluminium. Connew: “Herd’s background was in applied mathematics and aerodynamics, so I’m sure it was more considered than most designs of the day. It never struck me as a slippery shape, more as an efficient body designed to be produced very quickly It’s clear the car was built as a one-off”

Like most projects that gain traction within Formula 1, it seemed a very good idea at the time. Through 1967 we had seen the new breed of 3-litre F1 racing engines begin to hit their stride. As they did so it became visibly apparent from trackside – never mind from the driver’s viewpoint – that the power and torque of new-generation F1 engines was outstripping the chassis’ ability to transmit such performance to the track surface. Wheelspin and a lack of traction became the condition demanding a cure.

Into 1968, Mauro Forghieri and Ron Tauranac of Brabham tied in following the Chaparral-inspired route of applying initially tiny strutted aerofoils to their cars. This was to generate downforce which would load the racing tyres’ road contact without adding any great static weight to be accelerated, braked and reacted in cornering. But there was an alternative route, which several optimistic pioneers had previously explored. Instead of transmitting power and torque through just two driven wheels, why not split the requirement between a racing car’s all four? To handle five-litre supercharged straight-eight torque in 1932 Bugatti had built a pair of four-wheel-drive Type 53 grand prix cars. Harry Miller had built 4WD Indy Cars and in 1934 American entrant Frank Scully’s five-litre V8 version was shipped across the Atlantic for US pilot Peter de Paolo to drive in the Tripoli Grand Prix, finishing eighth, and in the AVUSRennen in Berlin, where the V8 threw a rod.

”In his two years with ‘Cosbodge & Duckfudge’, Herd took Duckworth’s elegant six-spoke wheel design for the 4WD car to grace his F1 March 701s”

Robert Waddy’s twin-engined special ‘Fuzzi’ was a Brooklands-built 4WD hillclimb favourite just before World War 2, and after it such wonders as Archie Butterworth’s AJB special pre-dated Harry Ferguson Research’s really serious Project 99 research vehicle, which emerged as the last front-engined grand prix car (so far) in 1961, winning the Oulton Park Gold Cup driven by Stirling Moss. The much-loved ‘Fergie’ went on to compete in the Tasman Championship and on the British and European hillclimb scene. It was also taken to Indianapolis where, with Jack Fairman driving, it demonstrated impressively sustained pace through the four banked turns. Andy Granatelli of STP promptly commissioned Ferguson to build him a 4WD car to accept his supercharged Novi V8 engine for the 1964 ‘500’. The car was (and remains) colossal, but it was also quite quick. However, driver Bobby Unser blamelessly became involved in a multiple collision and retired after only two laps. But he returned in the STP-Novi-Ferguson for the 1965 race, and while it again failed to finish at least it was the fastest non-Ford V8-engined qualifier – eighth overall.

Meanwhile, BRM had constructed its own Ferguson-transmission P67 4WD F1 test car in 1964, and after some intensive testing – mainly with Richard Attwood and Richie Ginther driving – they concluded that conventional rear-drive made a better F1 prospect. Largely because it was BRM, nobody believed it…

Ferguson Research’s four-wheel-drive technology then appeared in such diverse products as the 1966-71 Jensen FF ‘supercar’ and the Home Office’s 1968 batch of 20-odd 4WD Ford Zodiac Mark 4 police cars.

For Indy 1967 Granatelli then sponsored engineer Ken Wallis in building the STP-Paxton Turbocar for that year’s ‘500’. Wallis slung the driver’s cockpit along the right side of a box-section backbone chassis and a Pratt & Whitney ST6B-62 gas turbine engine along the left, powering a Ferguson 4WD system. ‘Silent Sam’, or ‘The Whooshmobile’, promptly dominated the race in Parnelli Jones’s hands, and looked set to win until a two-bit transmission bearing let go after some 492 miles…

Colin Chapman of Lotus, always insatiably hungry for innovation, was deeply impressed by the Turbocar’s Indy showing, and knew he and his people could do better still. The result was the 4WD Lotus-Pratt & Whitney 56 for Indy ’68 – sponsored by Granatelli and STP. The wedge-shaped Lotuses proved very quick, though poor Mike Spence lost his life in one during practice. Joe Leonard qualified his STP-Lotus on pole position, with Graham Hill’s second fastest, and Art Pollard’s 11th. On raceday, Graham’s Type 56 lost a wheel and crashed, Leonard led – ‘Whooshmobile’-style – until lap 191 of the 200. The green flag had just come out to end a caution period, and under acceleration both the Leonard and Pollard Lotus 56s snapped their fuel-pump drive-shafts. But still the message was clear – four-wheel drive looked very advantageous at four-turn Indy… but would the technology transfer to top-tier road racing?

“It looked as if four-wheel drive was coming in, and that would be a complete breakthrough”

Through the latter half of 1968 into 1969, Lotus, Matra and McLaren all invested heavily in designing and building a new generation of 4WD F1 cars. These were bright people, with vast experience, and high ambitions, and they were joined by one of the brightest of them all – Keith Duckworth of Cosworth Engineering, designer/creator of what was proving to be the epochal Cosworth-Ford DFV V8 F1 engine.

Now he determined to build a car of his own, to be DFV-powered – and it was going to use an advanced 4WD system derived from Ferguson experience, but created in-house at Cosworth Engineering. The company had come a long way since its creation in 1958 by then-Lotus engineer Mike Costin, and Lotus gearbox specialist Duckworth. They remained on good terms with their former Team Lotus colleagues – though the early thanks they received was to be nicknamed ‘Cosbodge & Duckfudge Limited’.

Their wondrous DFV V8 engine of course won upon its racing debut in the 1967 Dutch Grand Prix, powering Jim Clark’s brand -new Lotus 49. Duckworth would recall: “Mike and I were quite keen on cars (as well as engines…) and I soon appreciated that the important thing in racing is all about the proper use of… the tyre… Number one priority.” Everything else followed from that critical necessity. “With the DFV we had produced more power than the chassis of the day could cope with. It looked to me as if four-wheel drive must soon be coming in, and that would be a complete breakthrough.” He determined to play completely fair with his DFV customers even if Cosworth built its own car, and rather than “mess about” with an initial two-wheel-drive design, he thought that an immediate 4WD project would enable them to at least start equal whenever they would start actually racing…

He needed a designer, and at the 1967 Italian GP had “a quiet word” with Robin Herd of McLaren – who in three years had established himself as an outstanding new design talent. Yet despite his F1 designs of the McLaren M2B to M7-series, and his CanAm Championship-dominating M6A, Herd was still on “35 quid a week”, and Duckworth offered decidedly more for him to join Cosworth and to create for them a four-wheel-drive F1 car. Duckworth made a formal offer on October 27, 1967, which he accepted, and into that winter of ’67-68 a 4WD car design concept was quickly agreed.

Herd designed and detailed most of it, from its broad aluminium-skinned tub to its 4WD transmission layout, while Duckworth designed the central gearbox and its torque-split differential unit which distributed power to front and rear final drives. Mike Hall, ex-Lotus and BRM, drew the gearbox and casing in collaboration with Alistair Lyle. Duckworth hoped to persuade Jim Clark, no less, to leave Lotus and drive this frontier-technology Cosworth car, but on April 7, 1968 poor Clark was killed at Hockenheim… and many hopes for the project died with him.

Still, two tubs were constructed, one an exploratory exercise, the other a running prototype for testing. It was powered by the only magnesium-block DFV V8 built, saving a little weight to compensate “…for all the extra 4WD gubbins…” But according to Lyle, “the thick-wall main shells expanded more in magnesium than the aluminium, resulting in a loss of vital oil pressure. The car was actually down to the weight limit, but the low-tech diffs available made the handling too uncertain to give the driver enough confidence to go really quickly.”

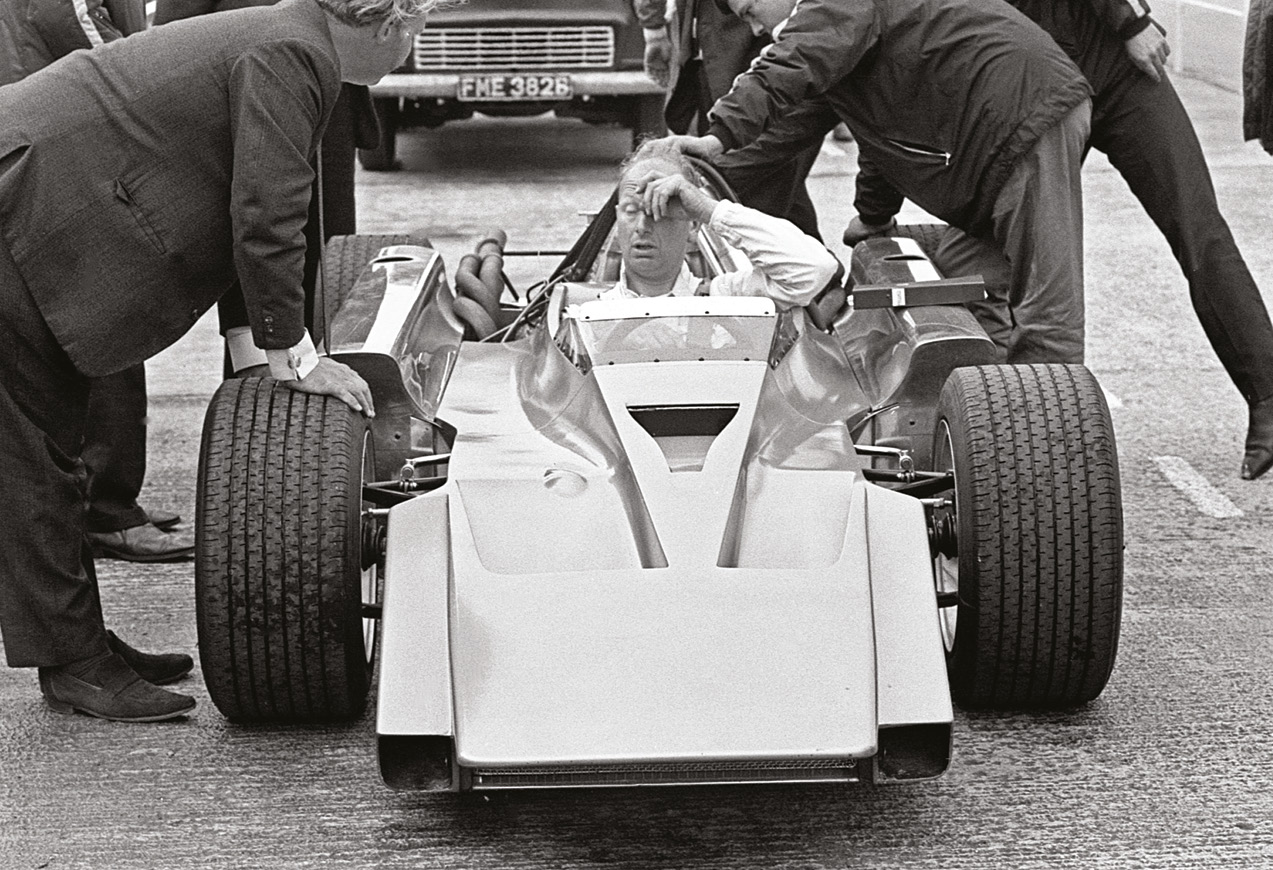

Mike Costin, a capable driver, tested the Cosworth at Silverstone early in 1969. A vague plan existed for Jimmy’s former Lotus No2 Trevor Taylor to drive it in the forthcoming British GP – but that didn’t happen…

Costin was bitterly disappointed by the car’s behaviour: “…down the straight it would gradually try to go off one way, I’d wind on more and more lock to stop that, and suddenly it would dive the other way, but I couldn’t get lock off fast enough to catch it!” Duckworth concluded such wandering was due to unequal tyre diameters, stagger as it would become known, amplified through the limited-slip systems. Costin found it wearingly heavy and demanding to drive. Taylor and Jackie Stewart also test drove, and readily concurred. Limited-slip rates were adjusted which achieved some improvement – but minor.

Duckworth: “Meanwhile, wings were solving most of the traction problems which had shaped our four-wheel-drive thinking in the first place. The car felt happiest when we biased more torque to the rear wheels, and less to the steerable front wheels – because that end’s behaviour was the biggest problem for the drivers. No way would I use only about 20 per cent torque on the front wheels and 80 per cent on the back, because then we’d just be lugging around all this extra weight and complexity for too little return. When we fitted even just a small rear wing, we found sufficient downforce to eliminate wheelspin – so there was no longer much advantage at all from driving the front wheels.”

“On the straight it would try to go one way, then dive the other”

In fact, he came to believe he had let the project continue for too long, and regretted having started it at all… having been seduced by what was, as Herd recalled: “a technically elegant piece of design”. Having invested around £130,000 – a very sizeable sum for the time – the plug was pulled.

The F1 4WD Cosworth was never raced. The complete test car was sold to enthusiast-collector Tom Wheatcroft for what became his now late-lamented Donington Collection, while the so-called pilot-build sister passed to Tom’s Australian counterpart Peter Briggs’s York Motor Museum. Herd and Cosworth parted amicably, and early 1969 he joined Max Mosley, Alan Rees and Graham Coaker in creating March Engineering. In addition to the broad-spectrum technical experience he had gained in his two years with ‘Cosbodge & Duckfudge’, Herd took Duckworth’s elegant six-spoke wheel design for the 4WD car to grace his 1970 F1 March 701s.

There’s usually a silver lining…