“Jesus, I was scared to death,” Roberts remembers. “I didn’t know where I was going and couldn’t see nothing. I’m racing with Sheene, thinking this is so stupid. One time I got sideways and was off the racetrack. I was up against a wall, doing 150 miles an hour. I got it straightened out, looked behind and Sheene’s eyes were that big.”

Ironically, Sheene suffered his two big smashes at purpose-built racetracks, the first of these disasters transforming him from aspiring World Champion into household name. In March 1975 he was testing for the Daytona 200 when his Suzuki XR11 750 triple suffered a catastrophic machine failure and slewed sideways at 175mph, the ensuing carnage filmed in gruesome detail by a Thames Television crew who were in Florida making a primetime documentary about Britain’s rock-star racer. Sheene broke a femur, an arm, a few ribs and several vertebrae in the accident. Surgeons hammered an 18-inch pin into the leg and seven weeks later he was racing again.

During the interim he had the camera crew at his bedside, the cheeky grin and the Gitanes cigarette (with filter torn off) burning brightly between the leg in traction and the arm in plaster. It was genius image-making, but no wonder people decided to love the man.

The cause is still disputed. Sheene always insisted the rear tyre came apart; others believe a broken chain tensioner was to blame.

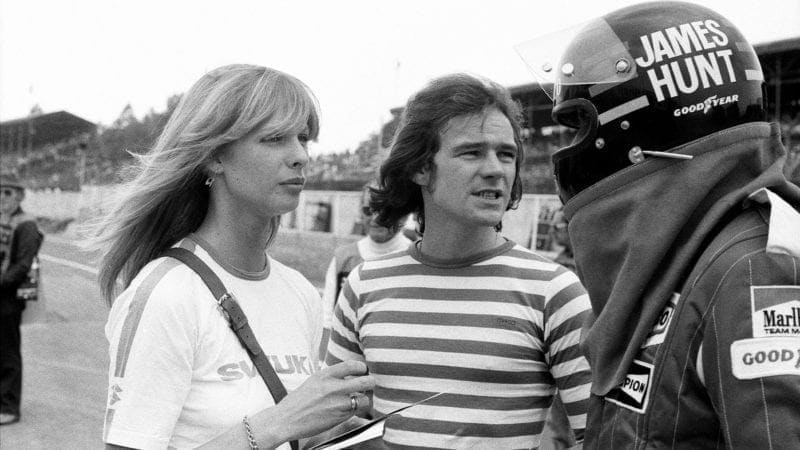

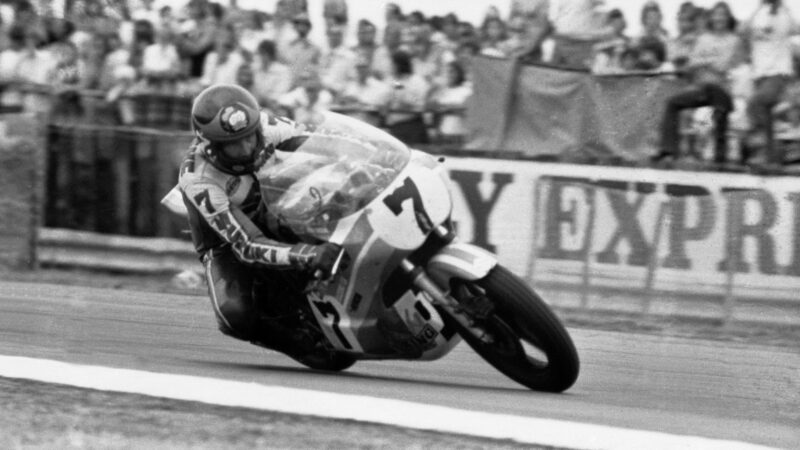

Sheene at Silverstone in 1975: he had been back on his bike seven weeks after a 175mph crash earlier in the year

Mirrorpix via Getty Images

Seven years later he was testing for the 1982 British Grand Prix at Silverstone when he collided with a fallen machine at 160mph, shattering both legs and a wrist. This time he was out of hospital in just 23 days.

The accident happened as Sheene crested the blind brow exiting Abbey Curve, head behind the screen, shifting into sixth gear. There were no marshals present and therefore no flags to warn him of Patrick Igoa‘s wrecked Yamaha TZ250 lying directly in his path.

Photos of the aftermath show a horrific scene — more air crash than motorcycle accident.

Once again the world got a grandstand view of his recovery and once again the bravery and the wit shone through. When a TV presenter asked him how his legs were coming along, he replied, “They’re great — I wouldn’t be without them.”

“To get the RG out of the paddock you had to scream it at 10,000rpm or it wouldn’t even clear”

Most people were quite rightly in awe of Sheene’s ability to shrug off pain, though Parrish knew there was an ulterior motive to the Lazarus-like comebacks; there nearly always was with everything he did.

“The speed of his recovery was phenomenal,” says Parrish. “And I’ll tell you why — because he wanted to be faster at recovering than anyone else. It was another competition, like who could get to the track fastest or who could swim the furthest underwater. Barry knew that if he got out there quicker than anyone else it would get him publicity which would help him get more money from the sponsors and better bikes. It was just part of the big game.”

It is telling that the X-rays of Sheene’s rebuilt legs — complete with several steel plates and two dozen screws — are as famous as any shot of him actually racing. Which brings us to the subject of the actual racing.

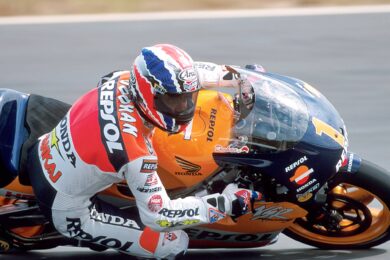

Sheene took the world by storm in the early 1970s. He nearly won the 125 World Championship at his first attempt, and two years later Suzuki signed him for 500 and 750 duties. In his first year as a factory rider he won the Formula 750 world title aboard the XR11 that would hurt him so badly two years hence. More important was the new RG500. It was Sheene’s good fortune that his arrival at Suzuki coincided with the introduction of the brilliant square-four RG, which went on to win 50 Grand Prix victories and five world titles.