Lunch with... Mark Blundell

His first home was a caravan, and the school of hard knocks was his only education. It would stand him in good stead on his climb to Formula 1 and beyond

Nowadays karting is the kindergarten, where aspiring hotshoes learn to feel through the seat of their pants. But it wasn’t ever thus. Stirling Moss began, at six years old, to absorb those lessons on horseback. Archie Scott Brown demonstrated his startling sense of balance as a kid in slow bicycle races, able to stay virtually stationary without falling over. Jacky Ickx’s huge talent as a wet-weather racer was seeded by teenage success in motorcycle trials.

As a schoolboy, Mark Blundell was a Top 36 ACU motocross rider. It taught him speed and control on loose, slippery surfaces; and it also taught him to be hard, to give and expect no quarter – playground training for the Formula Ford jungle to come: “When you’re 14 years old, in a line-up with 39 other kids handlebar to handlebar, you soon learn not to take any crap. You go into the first corner in a huge elbowing group, maybe in the lead, maybe on your face in the dirt with 10 bikes running over your back.”

After three decades in motor racing, including Formula 1, CART and Le Mans, Mark has still not retired. But most of his time is taken up by his thriving sports management company and various property interests. We meet at his period offices in Royston, Hertfordshire before he points his wheels that day, his wife’s Bentley Continental convertible, towards Cambridge and the Hotel du Vin. There he makes short work of avocado and crayfish, calves’ liver medium rare, sticky toffee pudding and a glass of one of the better Chardonnays. It’s a long way from his first childhood home, which was a caravan.

“My dad’s mother died when he was little, and when he left school at 13 he couldn’t read or write. My mum taught him all that later. His disadvantages drove him on to be the man he was. He started as a panel beater and sprayer, but really he was a wheeler-dealer, always working, always dealing.

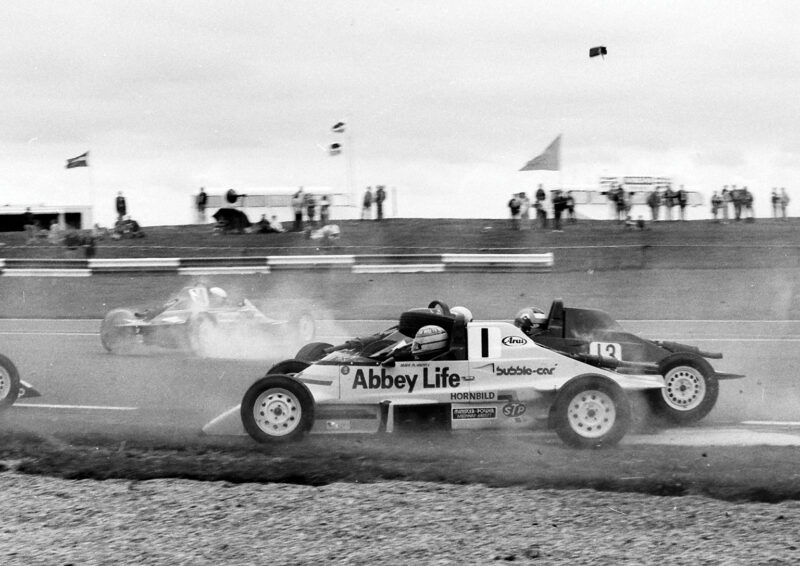

Blundell moved up to FF2000 in 1986

Motorsport Images

“He built up his wealth by car trading, then he went into property. As the money came in we moved out of the caravan into a house in Letchworth, and then a better house in Royston. My mum was the backbone of the family, brought up me and my younger brother and sister. Dad would be off each day at dawn and wouldn’t be back until I was in bed asleep. So I didn’t really get to know him until the motocross started. We’d all go off to that as a clan.

“When I was a kid nothing ever surprised me. My dad would have a poker night going, lots of his dealer mates round, and they’d be gambling really big. Someone would throw down a bunch of keys, or a Polaroid photograph. The photo would be of a Roller Silver Shadow, the keys would be to a villa in Majorca, and as the night went on they’d change hands around the table. Dad made a lot of money, and by the end he had his own yacht and a private plane. But he got caught in the last recession and the banks pulled the rug on him. He’d supported me in my early years, and by then I was in a position to return the favour. So he got his business back, and he’s still working hard. Today he’s bashing down a wall in a house he’s just bought. He loves to get stuck in.

“My need for speed emerged early on. When I was eight my dad had some of his stock in his yard, with the keys hanging up in the shed. I climbed into a Jensen V8, sat up on a cushion and started it up. My foot slipped off the brake onto the throttle. I wrote the Jensen off, and I managed to catch a Vanden Plas Princess and an Austin 1100 along the way. By the time I was 13, if I saw a nice car on his forecourt I’d sneak the keys from the office, go back at night and take it for a drive – a Ferrari Boxer, a Monica four-door GT, stuff like that. I never banged any of them, and my dad never knew.

“A couple of my mates were farmers’ sons who rode old motorbikes across the fields, and that’s how the motocross thing started. By the time I was 14 I was doing it seriously. I was never going to be a boy who knuckled down at school. I looked at my dad and his background and I thought, Well, he’s done OK. So I wasn’t exactly an A-plus student. Friday was bike preparation day, Monday was bike cleaning day, so I’d maybe turn up at school between Tuesday and Thursday. And when I was there I was a nightmare.”

Lucrative Nissan drive in 1989 led to Le Mans

Motorsport Images

Mark became a real force in the hurly-burly of motocross, winning championships and earning a reputation as a merciless competitor. “I had the opportunity to turn professional, but while I was on my two-wheel journey my heart was always hankering after four wheels. But we knew nothing about car racing. We’d heard of F1, but that was all. My dad said, ‘If you want to do Formula 1, I suppose you have to start in Formula 2 first?’ Then a car trader friend of dad’s took me to Snetterton and I saw Formula Fords for the first time. He said, ‘You can handle yourself on a bike, you ought to give this a go.’ So in February 1984, when I was still 17, I went to the racing school at Cadwell Park. After two days they said, ‘We can’t teach you any more. You need to go out and race.’

“We went to Lola because they were just up the road at Huntingdon, and bought a T644E. It was on the loose side, taught me car control pretty quickly, then mid-season we switched to a Van Diemen RF84. Coming from motocross, where you’d typically do four races in a day, we didn’t understand the mentality of just entering for one event. With all the championships, BP, Star of Tomorrow, P&O Ferries, and local things like Champion of Snetterton, there’d often be three FF races at a meeting. We said, Let’s do them all. It’s only tyres and fuel. That first season I did 70 races, won 25 of them, and got more poles and fastest laps than anyone else.” His efforts won Mark that year’s top Grovewood Award, ahead of Andy Wallace and Damon Hill, and the Autosport Golden Helmet for scoring more race wins than any other driver. Few novices have had a more successful first season.

For his second year Mark had a Van Diemen factory deal, and was rapidly gaining a reputation as a hard man. “I suppose I was a bit rough and ready. If I went into a corner side by side with somebody, rather than be the one to lift off I’d sooner not come out the other side, because I knew that next time it happened the other guy would be the one to lift. That was my psychology, and in Formula Ford it seemed to work. “My main rival was my, er, friend Bertrand Gachot. Throughout the season we had several incidents. At Castle Combe he moved across on me, put me on wet grass, I was heading for a marshals’ post and he didn’t pull back. How I missed it I’ll never know. Back in the paddock I grabbed Bert and told him to take his helmet off, but he wouldn’t. But he made the mistakeof lifting his visor, and I made a tight fist and got him straight in the eyes, through the slot. There were two local bobbies sauntering round the paddock, and they held me for a breach of the peace. But we talked our way out of it.

Ligier broke form and hired two British drivers for 1993, pairing Blundell with Brundle

Motorsport Images

“With Gachot and me it went on and on. I don’t know how many times we were up before the stewards, with Bert saying, ‘I don’t speak English, I don’t understand.’ Then we’d get outside and he’d sneer, ‘I’ve done you again.’ I won the Esso series, but in the Townsend Thoresen he just beat me, after a startline pileup in the final round at Thruxton. “For 1986 I moved up to Formula Ford 2000, and I was battling with Bert again. We had some real ding-dongs. I won the European Championship, he just pipped me in the British. There was a good crop of young drivers around then: Damon Hill, Johnny Herbert, Eddie Irvine, we all got to F1. Bert made it to F1 too, but then that thing at Hyde Park Corner ruined his career.” Gachot had an argument with a taxi driver after a traffic collision, and sprayed CS gas in the cabbie’s face. Convicted of actualbodily harm, he spent two months in a British jail. “It was a shame, because fundamentally Bert was a bloody good driver. I bumped into him at an airport last year and, 25 years on, we had a good chat. He now owns the energy drink Hype, and he’s doing pretty well.”

In 1987, not yet 21, Mark decided to make a brave move straight into Formula 3000. “A top F3 drive, with all the testing, was going to be £400,000. We said, ‘Where’s the rule that says you have to go through F3? Let’s make the jump.’ So we set up our own team, bought a secondhand car from Lola, and made do with a mechanically fuel injected engine when all the quick boys were on electronic. We nicknamed the car The Garden Shed because it was just held together with tape.” Remarkably, he very nearly won his third race, at Spa supporting the Belgian GP. It was Spa weather: in qualifying he was fastest until the track started to dry, leaving him fifth on the grid. More rain on race day, and Mark carved through brilliantly, passing cars right and left in the spray to take the lead.

“I’d learned from motocross to be observant, and read the surface. My lines were sometimes a bit strange, because I’d go two metres wide to find more grip. I arrived at the Bus Stop in second place, lots of spray, no visibility, and in front of me I could hear but couldn’t see the leader, Roberto Moreno in the works Ralt. I listened for him to lift off for the corner, counted to five, and came out in the lead. It was that kind of day.” A pile-up at Eau Rouge caused the race to be red-flagged and the official results took the positions at the end of the previous lap, so Mark had to be content with second place. But if any F1 people were watching, they’d have been impressed.

Telemetry measured impact speed of 175mph during 1995 Japanese GP shunt

Motorsport Images

For 1988 Mark was in a works F3000 Lola, although he had to find 40 per cent of the budget. “We had a couple of second places and a fastest lap, but we never got the results we felt were there. In 1989 I did F3000 with Middlebridge Racing, run by John Macdonald. That didn’t go too well either, apart from third at Silverstone and fifth on the streets in Birmingham. But 1989 was a turning point, because I got a Williams F1 testing deal. John Macdonald said to Frank Williams, ‘You’ve got to take a look at this kid’, and I ended up with a three-year contract. I was only paid £10,000 a year, but in the first season alone, developing the semi-automatic gearbox and the active suspension, I did 32 days’ testing, a huge amount of miles. It taught me so much, working alongside Riccardo Patrese, Thierry Boutsen and Patrick Head. I really looked up to Patrick, he was very supportive and seemed to trust me. Every so often I’d go into Didcot and report to Frank on how things were going. Always straight-forward, no fuss, you knew where you stood with Frank.

“But I needed to earn some proper money, because I’d done F3000 on a series of loans which had to be paid back. Nissan’s World Sportscar programme used a Lola chassis, and my Lola connections got me in there. I signed with them alongside Julian Bailey, and they paid me £150,000 for seven races, which was good money in 1989. We got podiums at Spa and Donington behind the Mercedes, but my first Le Mans was over before it began. Five laps after the start Julian ran into the back of a Jaguar. We spent the rest of the 24 hours at the funfair and in the town centre fountain.”

For Le Mans 1990 Nissan made a huge effort, with five works cars, and Mark caused a sensation by qualifying with a blinding balls-out lap in 3min 27.02sec, six seconds faster than anyone else. Despite the new chicanes on the Mulsanne Straight that year, it was an average speed of 147mph. “I was doing the race with Julian and Gianfranco Brancatelli. Julian and I tossed a coin to decide who would qualify and who would start the race. I won the toss, and I knew Nissan had done a monster qualifying engine, so I opted to qualify. Julian was cock-ahoop because he was starting in front of all the Porsches and Silk Cut Jaguars.”

Le Mans win for Peugeot in 1992, overseen by Jean Todt

Motorsport Images

Sure enough Bailey, Blundell and Brancatelli led Le Mans for the first four hours, until Brancatelli hit another car and damaged the bodywork. After a long delay they climbed back to sixth place, then during the night the gearbox failed. “But Julian and I got second place in Montréal, and third at Dijon and in Mexico. That was the last round, so we partied afterwards. We went to the Magic Circus, a tented nightclub which held 1000 people. They had big cages suspendedfrom the roof for the dancing girls, and Bailey, [Johnny] Dumfries and I decided it would be fun if we took our bottles of champagne into one of the cages. Didn’t go down too well with the locals, so we ended up in that cage for a long time.

“For 1991 I’d signed heads of agreement with Tom Walkinshaw to take over Martin Brundle’s sports car drive at Jaguar, because he was going back to F1 with Brabham. When the contract came through the £60,000 win bonus we’d agreed had gone missing. I called Tom, and he said he’d never accepted that, although it was in the heads. Then I had a call from Brabham. They’d been taken over by Middlebridge, which was Koji Nakauchi and Dennis Nursey. Lots of people I knew were in it: John Macdonald, Herbie Blash, Dave Price who’d been running the Nissan sports car team. And Yamaha were on board to supply the engines. They’d signed Martin Brundle, and they wanted to sign me. I was 24, and I thought, this is my big break. I’ve made it. Forget sports cars, I’m going to be a paid F1 driver. It was one of my less well thought-out decisions. I wish I’d had somebody around me strong and experienced enough to tell me to stay put, but I didn’t have a manager, I was doing it all myself.

“Martin and I had to go to Japan for the press announcement. Koji Nakauchi was the billionaire team owner, and we expected to be met by his staff at the airport and whisked in to the city to meet him. But when we landed at Tokyo there was just him waiting to meet us. He led us out into the car park, and Martin and I looked at each other when we saw his car, which was an old Rover SD1. That was the first sign that it didn’t all quite add up.

“I did have a good race at Spa, qualified well and finished sixth, which earned Yamaha’s first championship point. And I put it on the sixth row at Monza. But the Brabham was terrible. They just didn’t have the budget to do things right. I was still contracted to test for Williams, and I remember doing the GP at Imola in the Brabham – managed to finish eighth, but I was lapped three times – and then the next day I was testing the Williams FW14 on the same circuit, and I was an easy 2.2sec faster on race tyres than I’d been in the Brabham on qualifiers. That was when I realised I’d made a big mistake. Twice during the year my salary cheque bounced, and I had to go to Chessington and say to Dennis Nursey, I’m not leaving until I get my money. This was glamorous F1.

Works F3000 campaign in 1998 (Birmingham Superprix pictured) did not prove fruitful

Motorsport Images

“The Japanese commentators had a nightmare coping with Brundle and Blundell in the same team, because the Japanese characters for L and R are the same, and we always got mixed up. At the end of the season there was the 11-hour flight from Tokyo to Adelaide, and I had to turn up early because I was in economy. Martin, the superstar, always flew first class. I checked in, and was presented with seat 2A. Nice, I thought, they’ve given me an upgrade, they must know I’m a real F1 driver. I’d just made myself comfortable when the little Japanese air hostess asked to see my boarding card. ‘Prease, you need to move back.’ ‘No’, I said, ‘This is my name, this is my seat.’ Martin’s in the doorway, seething, red in the face and you can see he’s been arguing for a long time. Everyone else in first class were F1 people, they thought it was good sport, and were all rooting for me. I refused to budge, so Martin had to sit for 11 hours back in 62J. He still hasn’t forgiven me.

At that Adelaide race at the end of 1991 Ron Dennis sent Jo Ramirez to find me. In the McLaren motorhome Ron said, ‘We’ve seen you testing for Williams, and we’ve seen you racing for Brabham. You’d be better off working with us than being at the back of the grid with an underfunded team. Come and be our test driver.’ That gave me a fantastic year working with Steve Hallam, Neil Oatley and the others, and with Honda. And I got to work with Ayrton [Senna] and Gerhard [Berger].

“Ayrton used to take long winters in Brazil and come back just before the start of the season. I remember him coming to a test, listening to me talking with the engineers, watching how I got on. He wanted to check up on me, then he kind of rubber-stamped me and went away again. As the season went on I got to know him better, talked with him a little bit. Intense, committed, focused, very driven, very selfish. I went to all the races as reserve driver and to do promotional work, and I remember on the plane he had all his press cuttings laid out, marked with highlighter pen wherever he was mentioned. He was going through them all minutely, reading everything that was said about him. I couldn’t work out why a guy of his stature would bother with that.

“During one test day at Imola I was in the ‘active’ car, and I matched Ayrton’s time in the ‘passive’ car. Obviously the active car was very good and fully operational by then, but he couldn’t quite get his head round the time I’d done. That was my last day but the others were staying on, and Josef, Ayrton’s Austrian fitness guy, had been detailed to run me to the airport at Bologna. We were all in the truck having the debrief, and I said, ‘Josef, we need to leave now so I can get my plane.’ Senna lifted his head from reading the sheets and said quietly, ‘He stays here with me.’ I said, ‘It’s OK, it’s been arranged that he can just run me to the airport.’ ‘No, he stays here with me. You make other arrangements.’ Nobody else said anything. It was just Ayrton’s way of putting me back in my place. You’ve done your job today, but don’t forget who is boss here.

McLaren MP4-12C GT3 campaign is the focus for 2012

Motorsport Images

“Gerhard was a great guy. When I tested his car I couldn’t get on with his set-up at all. He had everything on the nose, very loose, whereas I liked the centre of balance much further back in the car. As a bloke he was an oversteerer too, forever pushing, jovial, joking. In the end he even got Ayrton to crack a smile. He was always sneaking into Ayrton’s hotel room, wrapping up something unmentionable and stuffing it down his bed.

“McLaren were in discussion with Peugeot about using their V10 for 1994, so Jean Todt, who was then Peugeot’s competitions boss, asked Ron to release me to do Le Mans. It was my one race in 1992. And we won it.” Mark, with Derek Warwick and Yannick Dalmas, led from the second hour until the end. “Le Mans is still one of the three biggest races in the world. Everybody wants it on his CV. Winning in France for a French manufacturer is pretty good, but then at the end standing on the gantry as a Brit, with your British team-mate, andlooking down on that sea of Union Flags, that’s something else again. In a big team there’s camaraderie but also pressure, eight months’ work focused on a single weekend. Yannick is a lovely guy, and Derek I’ve always looked up to. We’re similar, we think the same way: solid, no bullshit, just do it. I was friendly with Derek’s brother Paul [killed in an F3000 crash in 1991]. He had raw ability in shedloads, and with Derek’s help he was going to go all the way.

“For ’93 I got an F1 race deal again. I was the first British driver to be signed by Ligier – and then, once they’d got me, bizarrely they signed Martin, so the Brundell Brothers were together again. The JS39 had the Renault V10 engine, and it was a good little car. In my first race with it, at Kyalami, I finished on the podium. And again at Hockenheim: when I came out after my tyre stop I was behind Berger’s Ferrari, and he was making it very wide. I had to put two wheels on the grass at 200mph to get past. But it wasn’t easy being a Brit in a French team, because I didn’t speak the language. Martin had the upper hand there, because he’d had some education and spoke a bit of French.

Works Van Diemen FFord drive for 1985 established Blundell’s hard man credentials

Motorsport Images

“There was always massive competition between me and Martin. Because we lived quite close we used to share a plane to European races out of Norwich Airport. At Estoril we were running together and had a bit of a thing: basically he pushed me onto the grass at about 180mph. I was pretty sore about that. Martin knew what my temper was like, and off-track he was a bit wary of that. Didn’t stop him being a bulldog on the track, he’s as hard as anyone. We got on the plane home and we didn’t speak for two hours, just sat behind our newspapers. When we landed at Norwich we put our papers down and looked at each other. ‘You all right?’ ‘Yeah, you?’ ‘Yeah. Speak tomorrow?’ ‘Speak tomorrow.’ And we went home. I was mad because he put me off the track, he knew I was mad, but there was a friendship underneath it. We slept on it, and we talked next day as usual.

“And of course the two of us ended up starting a business. My sports management company, 2MB, was a joint enterprise with Martin, although he’s out of it now. And later we did TV together. We’ve spent a lot of time in each other’s pockets. As team-mates at Brabham and again at Ligier we went everywhere together, which is rare in F1 now. We shared the same rental cars, shared the same hotel rooms. Once we shared the same bed, because the room we’d been booked in had a hole in the roof and there was a bird flying around the room crapping everywhere. We had to drive around and all we could find was a single-bedded room. Like I said, glamorous F1.

“For 1994 I got picked up by Tyrrell. I really liked Ken, he called a spade a spade. And I had a good relationship on the technical side with Harvey Postlethwaite, who was a smashing guy. It was back to Yamaha engines again, and I scored their first-ever podium when I was third at Barcelona. It was also, sadly, Tyrrell’s final podium. I was in the points at the Hungaroring and Spa, but then McLaren came after me again with a testing deal for 1995.

Second for Bentley at Le Mans in 2003 after losing time to technical trouble

Motorsport Images

“McLaren’s race drivers for the season were Mika Häkkinen and Nigel Mansell, but unknown to me there were already some issues with Mansell. I signed on as test driver, at test driver money, but there was a clause in my contract that said if they called on me to race I’d get no extra money. And that’s what happened.” Mansell missed the first race, in Brazil, because he had difficulty fitting in the car – and Blundell finished in the points. Mansell ran at Imola and finished 10th, two laps behind after two collisions, then at Barcelona he slid off the road and pulled out, complaining of handling problems. It was the end of his F1 career.

“I first knew Nigel when I was test driver at Williams. Something needed trying, I forget what, and I heard him say, ‘Get the test monkey to do it.’ When I took his drive at McLaren I wanted to make some monkey comment in return, but never got the chance. The chemistrybetween him and McLaren was never going to work, there was such a difference of personalities. So I ended up doing the rest of the season in the MP4/10-Mercedes. But one of my issues with Ron was that, even when Nigel was long gone, he left me on a race-by-race contract. He said it would put me under more pressure to perform, but that was the wrong way to go about it. I wanted to feel part of the team, but I always felt I was on trial.”

That season Mark finished in the points six times for McLaren, qualifying on the third row at Spa, and finishing fourth at Monza and Adelaide. But his bravest race was surely Suzuka. On Saturday morning, at the hugely quick 130R corner, he had an immense accident. As he hit the tyre wall McLaren’s telemetry recorded an impact speed of just over 175mph. Stunned, winded and bruised, he was advised to sit out qualifying that afternoon. A spare tub was built up overnight and he started from the back of the grid. “I still had double vision from the crash, but I came through. If the pitstops had been called a bit differently I could have been in the points. As it was I finished seventh.

“For 1996 David [Coulthard] was coming into McLaren, but I’d got an agreement to go to Sauber. Then Dietrich Mateschitz got involved and insisted they had a driver who’d won a GP, so they switched to Johnny [Herbert] instead. At this point I got a bit disheartened and thought, ‘screw this, I’m going to Indycar’.

Blundell manages 16 footballers and four racing drivers from his offices in Royston

After my time at McLaren, Mercedes said they’d support me, and whichever Indycar team I went to could take their engine. I went to PacWest. The family moved to Miami – Mark Jr was nine then, Callum was a little tot – but eventually we moved to Arizona. Great place: we’ve still got our house in Scottsdale.

“My second Indycar race, in Rio, I had the biggest accident of my career. I’m lucky to be able to talk about it, because it should have cost me my life. A front hub disc brake bell broke – not a Reynard part, a piece that had been manufactured for PacWest in the US. Head first into the wall at 198mph. The impact was measured at 122G. What stays in my mind is the ferocious noise it made, hitting that concrete. After the restart the same part broke on my team-mate Mauricio Gugelmin’s car, but for him it happened on the back straight, so he just ran along the wall and stopped.

“I had two days in hospital in Brazil, broken bones in my feet, various other injuries, knees, ribs, cartilages, but they didn’t give me anything like a brain scan. Just a couple of paracetemol. I flew home and by the time the plane landed I had the worst headache I’d ever had in my life, felt like my head was going to explode. My dad took me straight to hospital, they scanned me and found I had a blood clot on the brain. They said if the clot had burst in the air I’d have been dead. But gradually it dissipated on its own, and I was racing seven weeks later.

“I had some of the best racing of my life on the big ovals, lovely 200mph-plus stuff. I won the 500-miler at Fontana in 1997. On that track you’re doing 248 on the straights and 227 in the corners, and every 15 seconds you’ve done another mile. The cars are so evenly matched. Even if you’ve been an F1 driver, you’ve never experienced what it’s like to run in a big Indycar pack. It’s not so much the speed, it’s the close proximity, you get buffeted around. The short ovals were something of an art form and I struggled on those, but in 1997 I also won at Portland, a road circuit, beat Gil de Ferran by 27 thousandths of a second. Closest finish in Indycar history. Four weeks later at Toronto, a street circuit, I led all the way with Alex Zanardi on my tail. Won that by 65 hundredths.”

In 1999 Mark had another big accident. Testing at St Louis, a gearbox problem put him backwards into the wall, and severely injured his back. He was out of racing for three months. He remained with PacWest until the end of the 2000 season, and in the meantime did some F1 TV commentating with Murray Walker when Martin Brundle was busy at Le Mans. This led to a permanent place on the F1 ITV team, although Mark admits he wasn’t always comfortable in the role. “I did enjoy it, and ended up doing it for seven years. But I don’t have a good education, and I didn’t really have the vocabulary. Some people loved it and some hated it: he can’t talk properly, they said, he’s got an accent. But it’s no good me trying to be something I’m not. I can only explain myself in my own way.

“I did Le Mans for MG in ’01 and ’02 in the little Lola EX257 with Julian and Kevin McGarrity: in the wet we ran third on the road for a long time. Then in 2003 it was Bentley with David [Brabham] and Johnny [Herbert]. We were third at Sebring and we should have won Le Mans, but we were let down, twice, by £1.50 battery terminals, and in the end we were second to the other Bentley.

“After that I didn’t say I’d retired, I just focused on building up my company. I’d always had things going on in the background, because I knew motor racing was fickle. But in 2010 Zak Brown and Richard Dean, who run United Autosports, offered me an Audi R8 for the Spa 24 Hours. We finished fourth in class. Then last year, in the Daytona 24 Hours, I found myself back with Martin in Zak’s Riley-Ford. We surprised a lot of people, finished fourth overall. I did some more Grand-Am races, and Spa, and also the Nürburgring 24 Hours on the Nordschleife with Johnny Herbert in a 500bhp turbo five-cylinder VW, a very lively little car. That’s the only race I’ve ever felt that I don’t want to go back. Love the track, but 250 starters, and horrendous speed differential – and ability differential – through the field.”

This year Mark will be driving one of United’s GT3 McLarens in the Blancpain series around Europe. He’s relishing the prospect. “I got myself in reasonable shape for Daytona last year, but I need to do more. What I lack in fitness I can carry through with brute strength. But I’ll pay the price afterwards.

“Meanwhile the businesses are keeping me up to it. We look after 16 footballers now, and four drivers: DTM racer Gary Paffett, Indycar man Mike Conway, and two youngsters who you’ll hear a lot about soon. And I’m doing consultancy work – I’ve been twice to Saudi Arabia recently, where a developer is talking about the grass-roots potential of a circuit out there. But I’m looking forward to racing seriously, and racing hard, with the McLaren this year. So don’t ask me if I’ve retired….”

Simon Taylor