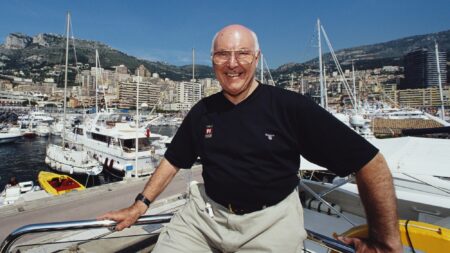

Murray understands this, and so — love him or loathe him — Murray is Murray. I can confirm, having worked with him and been proud to call him a friend for over 30 years, that in the commentary box or out of it he doesn’t change. He talks in exactly the same way whether he is holding a microphone or a knife and fork. He is a wonderful raconteur, and his personal insights into the characters he likes or respects — and those he doesn’t — are vividly expressed. And his delivery is always the same. He enunciates every syllable with great clarity: commentary is pronounced ‘commentary’ rather than the more usual ‘comment-ry’. He loves adverbs. Rarely is an adjective allowed to stand alone without an adverb to increase its power. For Murray, a man is not just clever: he is enormously clever. A car is not just quick: it is gigantically quick. When something surprising happens he is not dumbstruck: he is literally dumbstruck. (Which is unlikely: whatever else Murray might be, he is never, ever struck dumb.) And, lest you should not be totally convinced of the force of what he has just told you, he will often add a favourite phrase: “…to put it mildly”.

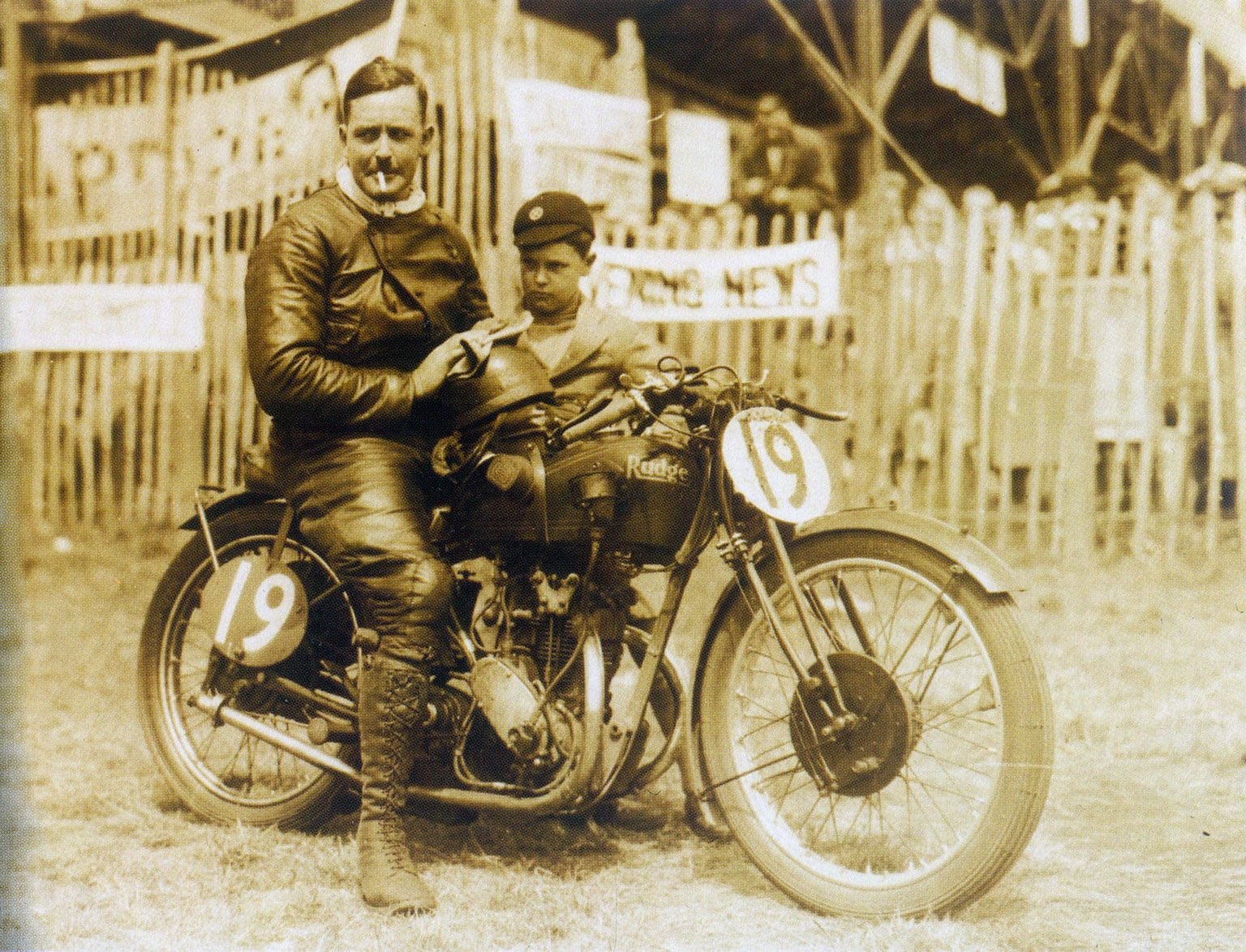

The child is father of the man, and Murray’s happy childhood set him up for life. His father was a top motorcycle racer. Works rider for Rudge, Sunbeam and Norton, Graham Walker was European Champion, and dominated the 1928 Senior TT until his bike broke on the final lap. He won the first motorcycle Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, and in winning the Ulster GP became the first man to average over 80mph in a two-wheeled road race. “He was kind and brave, and I grew up admiring and respecting him, and wanting to be like him.” In 1935, having retired from racing, Graham began doing radio commentaries for the BBC, and edited the magazine Motor Cycling with great flair for 16 years.

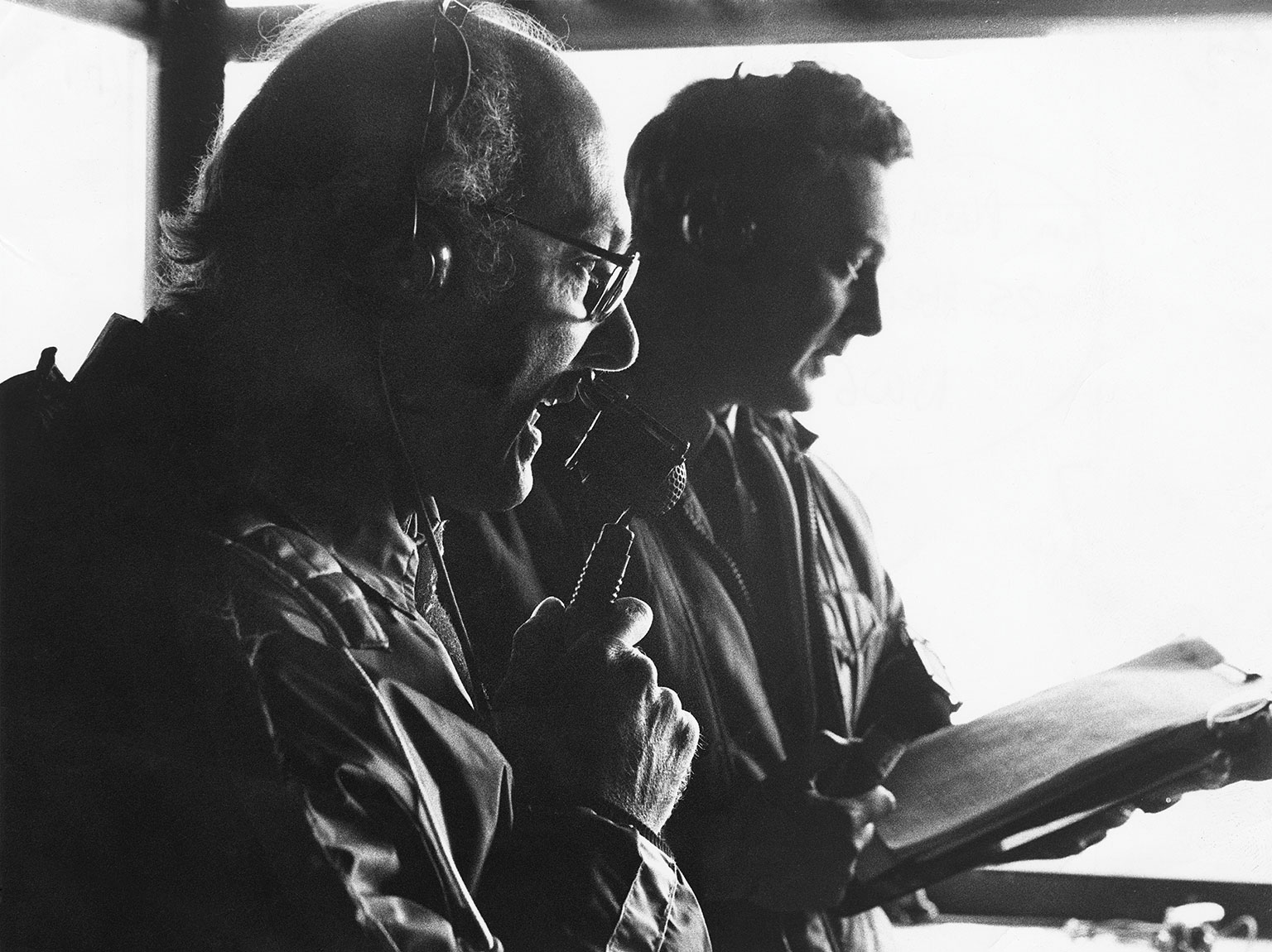

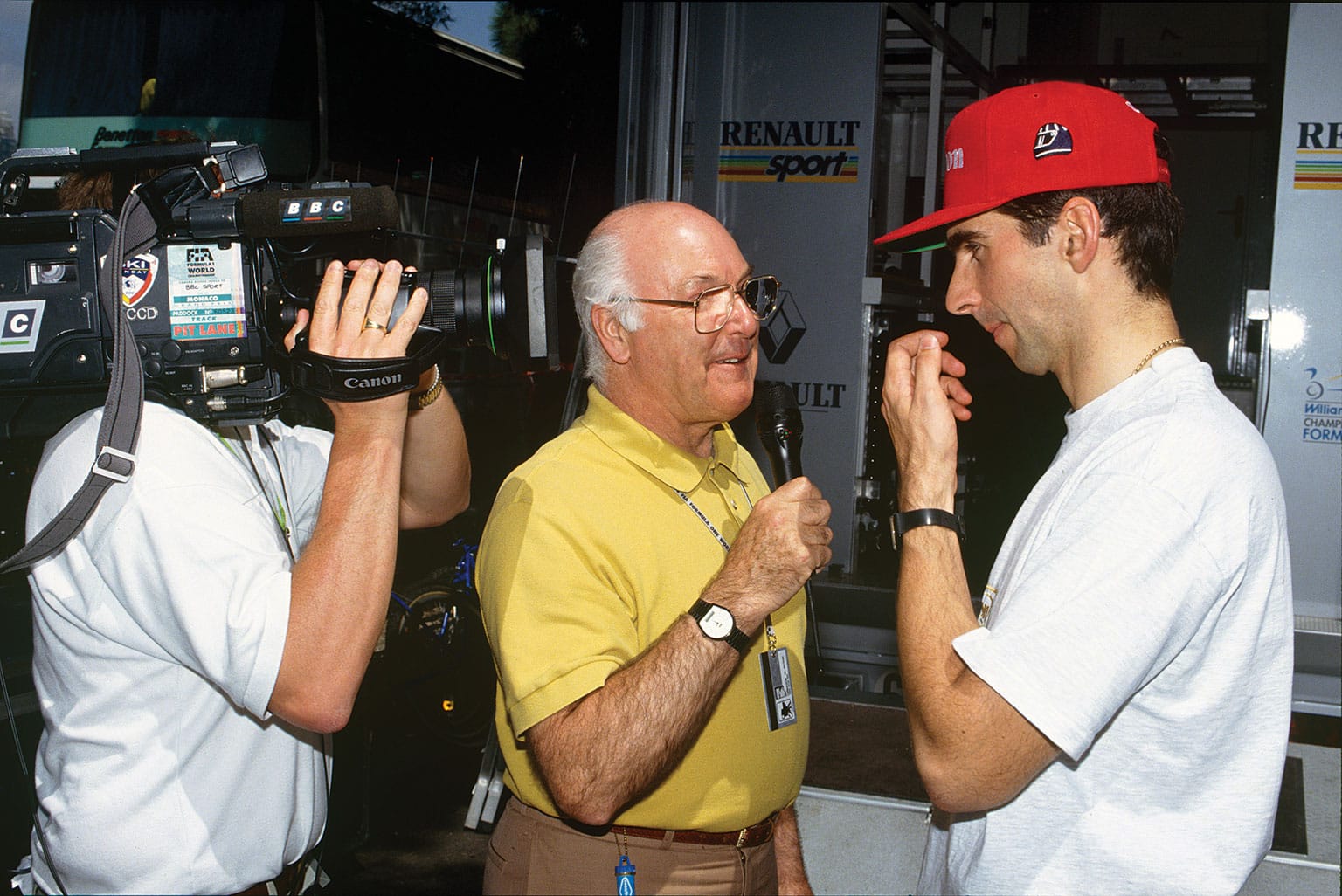

Sharing the talking with Barrie Gill

Courtesy of Murray Walker

So Murray grew up in an atmosphere of motor sport. He first went to the Isle of Man TT races when he was two years old. In 1938 a family friend acted as interpreter for the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union teams when they came to Donington, and Murray, a starstruck 15-year-old, was there to see Nuvolari’s Auto Union win, and to rub shoulders with Caracciola and Rosemeyer. Then came World War II. “War brought misery, pain, deprivation and tragedy, but — it’s a terrible thing to say — it also brought excitement. If you were a teenager there were three things you aspired to: fighter aircraft, submarines, and tanks. I wore spectacles, so Spitfires were out, and I didn’t fancy being under water. So I volunteered for tanks.” He was part of the invasion crossing the Rhine in March 1945, and ended up with the rank of Captain. “It’s a cliche, but ‘in as a boy and out as a man’ was certainly true in my case.” When peace came he got a job with the Dunlop Rubber Company, and found himself working in its advertising department.

“My phone rang. ‘You busy on Saturday, Murray? I want you to cover Weightlifting’”

“I started racing bikes, probably because I thought my father would want me to, rather than because I passionately wanted to. I raced against the young John Surtees — well, I used to watch him disappear into the distance, and saw him again when he lapped me — and the pinnacle of my achievement was winning a 250cc heat on the old anti-clockwise grass track at Brands. I realised racing wasn’t for me, so I switched to trials, and did rather better. On my 500T Norton I won a gold in the International Six Days’ Trial, and I won a first-class award in the Scottish Six Days.” Then in September 1948 something happened to change Murray’s life.

“My father was due to do radio commentary from a combined bikes and cars meeting at Shelsley Walsh, but at the last moment he had a clashing engagement. So the public address commentator, a man called Charlie Markham, was asked to do the BBC broadcast. When the event organisers asked my father if he had any suggestions for a PA replacement, he said, “Well, you could give the boy a go.” Now with PA you tell the spectators what they are going to be watching, and then you let them watch it. Not me. I subjected them to a non-stop barrage of commentary, knowing the BBC people were there and could hear me.

“It must have worked, because at the Easter Monday Goodwood meeting in 1949 I was given a BBC audition. My trial was recorded onto a disc via a huge contraption in the back of a Humber Super Snipe, to which my microphone was connected by a length of wire, so I couldn’t stray any further than my wire allowed. And four weeks later I found myself doing my first live radio broadcast — from the British Grand Prix at Silverstone, positioned out at Stowe. The main commentator was Max Robertson, who was the BBC’s tennis commentator. He knew as much about motor racing as I knew about fly-fishing — and, moreover, he actively disliked it. Using the circuit layout where they charged up the main runways towards each other, the race was won by Baron de Graffenried’s 4CLT Maserati from Bob Gerard’s ERA and Louis Rosier’s Talbot. Towards the end of the race, which lasted nearly four hours, John Bolster’s ERA suddenly came cartwheeling down the track towards my box and deposited its driver in an inert heap just in front of me. I thought, ‘Blimey, they didn’t tell me what to say about something like this.’ So in a masterpiece of understatement I just said, ‘Bolster’s gone off!’ He survived, but he never raced again.

With father Graham in 1932

Courtesy of Murray Walker

“Then I got sent to the Isle of Man, and that was the start of a 14-year commentary partnership with my father for TT week. I found myself the BBC’s motorcycle man on races, scrambles and trials, and I also did the public address at just about every circuit in the land, learning my craft. It was only bikes then: car racing became the preserve of the urbane and enormously competent Raymond Baxter, with support from Robin Richards when they needed a second voice.

“My first TV broadcast also came in 1949. It was a motorcycle hillclimb, just a sort of filler really, and the young Peter Dimmock was the producer. The camera was the size of a large wheelbarrow, and it was all pretty primitive. Then ITV pioneered motocross, and I did that. It became very popular. In the dreadful winter of 1962 the whole country was snowed in, all sport was stopped, and somebody at the BBC decided, ‘We’d better do one of those motorcycle scrambling things.’ Dave Bickers was the sport’s big hero then, and at the start of this BBC event he stalled, and got away a lap after everybody else. He stormed through the field, and by the start of the final lap he was closing on the leader. The BBC producer in London shouted down the line, ‘This is bloody marvellous. Get them to do another couple of laps.’”

“James Hunt? I was literally gobsmacked. What the hell did he know about broadcasting?”

Meanwhile Murray’s business career blossomed. From Dunlop he went to Aspro, and then joined the agency world at McCann Erickson. In 1959 he moved to Masius Wynne-Williams, where he remained for 23 years. His stories of his life in advertising — on accounts like Mars, Vauxhall, Babycham, Embassy cigarettes, Weetabix, Wilkinson Sword — are manifold and hilarious. But somehow his prodigious energy allowed him to combine a hectic working week with ever more commentary work. Murray is a man who never likes to say no to anything.

“One Thursday, sitting at my desk at Masius, my phone rang. It was the top man at BBC Sport, Paul Fox — now Sir Paul — whom everybody feared like God. ‘You doing anything on Saturday, Murray?’ Saturday was my wedding anniversary. ‘No, Paul.”Right, I want you to go to Bristol and cover the Commonwealth Weightlifting Championships. Don’t say you know nothing about weightlifting, because neither does anyone else.’ I went through the phone book, found something called the British Weightlifting Association, phoned them up and asked to speak to the top man. They put me on to one Oscar State, who turned out to be the Max Mosley of weightlifting. I offered him a lift to Bristol — ‘provided you talk to me about weightlifting.’ He said, ‘I never talk about anything else.’ I went home, got Elizabeth to find me a broom handle, and spent the evening practising the Press, the Snatch and the Jerk. Mr State filled up my brain on the way to Bristol, and the programme went fine.

“But fundamentally I was the chap who did all the motorcycle stuff. I had the great privilege of living through and talking about a golden era of bikes: British machines like Norton, Velocette, AJS, men like Geoff Duke, John Surtees, Mike Hailwood, Barry Sheene. Mike became a close friend. His father was the millionaire owner of a string of motorcycle dealerships, ruthless and determined, and Stan poured money into Mike’s racing. He got Ducati to make special bikes for him, he hired top tuner Bill Lacey exclusively to work on his engines, and Mike always had the best. But it wouldn’t have been any use if he hadn’t had the ability, and he had the ability to genius level. He was also a wonderful man, totally laid-back, the ultimate party animal.

“Barry Sheene was a lovable cockney rogue, but also extremely bright: spoke fluent Spanish, spoke Japanese, an extremely good self-taught engineer. Everybody liked Barry, and Barry liked everybody. In live interviews he’d say the most outrageous things and get away with it, when anybody else would have given grave offence.

Murray Walker and James Hunt shared a microphone for 13 years

“Put a microphone in front of John Surtees in his two-wheel days, and he’d answer any question with one word. You’d go blundering on, trying desperately to get more than a monosyllabic response. Now with John you put a penny in the slot and it never runs out. He’s a forceful, opinionated character, but his opinions are always very much worth listening to. He has principles, and he sticks to them through thick and thin — which is why he walked away from Ferrari in 1966.

“As the BBC gradually covered more four-wheeled stuff I did it: F3, touring cars, Formula Ford, truck racing, anything with an engine. Except Formula 1. What little they did of that remained Raymond Baxter’s preserve. Then at the end of 1976 James Hunt won the World Championship, and suddenly Britain was waking up to Formula 1. So for 1978 BBC TV decided to do a Sunday evening programme called Grand Prix — half an hour of highlights from that afternoon’s race, taking the pictures off Eurovision. By then Raymond Baxter had a major commitment to Tomorrow’s World, so they asked me to do the commentary. That’s where it all really began. I would go out to each Grand Prix on the Thursday — only the European ones, because the budget didn’t run to the long-haul races — mooch about, talk to people, watch Saturday qualifying and then fly back to London on Saturday night. On Sunday afternoon I’d watch the Eurovision feed at Television Centre, they’d edit it down to a tight 27 minutes and I’d dub the commentary on afterwards. Sometimes the edit was only finished at the last minute, so I’d have to commentate as the programme went out, doing it all as though I was there. You’d jump from lap five to lap 23, and vital chunks had to be left out. It was extremely demanding.

After the 1979 Monaco GP James Hunt got out of his Wolf and walked away from his career as a racing driver. And our producer, Jonathan Martin, had this revolutionary brainwave. He called me in and said, ‘Two commentators in future, Murray. You’ll be one, the other will be James Hunt.’

“James Hunt? I was literally gobsmacked. To put it mildly. What the hell did James Hunt know about broadcasting? He was a racing driver! And one I didn’t much like. I was old enough to be his father, and we were out of two different moulds. To me he was a rude, arrogant Hooray Henry who drank like a fish, smoked like a chimney, and womanised like there was no yesterday, let alone tomorrow. Plus, all commentators are insecure, it’s the nature of the business. I thought: it’s the thin end of the wedge. They’re pushing him in and pushing me out. So, due to a combination of insecurity and actual dislike, I wasn’t best pleased.

“The first Grand Prix we did live from the circuit was Monaco 1980. There were no commentary boxes then: just two folding chairs out on the pavement behind the Armco and a flickering little TV monitor. car-pieces in, cars lined up, no sign of James. With two minutes to go he shambles up, barefoot, jagged jeans shorts, dirty T-shirt, half-drunk, bottle of rose in his hand. Slumps into the chair and takes a swig from the bottle. And God, his feet smelt.

“But the amazing thing is, the broadcast went all right. Because, of course, James was a brilliant choice. He was famous, he was a World Champion, he had the knowledge and he had the eloquence. Our styles couldn’t have been more different, which was maybe why it did work. I’d be bouncing around on the balls of my feet, a metaphorical bucket under each foot to collect the adrenaline that was literally pouring off me, to put it mildly, and James would be slumped in a sullen heap beside me, bottle at his side. It’s well known that Jonathan Martin made us share a microphone so we didn’t talk over one another. Very sensible with two egotistical people in the box, each of whom knew that what he wanted to say was infinitely more interesting and important than anything the other bloke had to say. I’d reluctantly pass the microphone to James and, while he was still talking about how many pounds per square inch there were in the tyres, I’d be trying to wrestle it back from him because something faaantastic had just happened. I must have been very hard to put up with.

Interviewing Nigel Mansell after his 1992 championship win… with his mic switched on…

Motorsport Images

“I don’t think there is such a thing as a dull motor race, but if things did need livening up a bit I only had to say something complimentary about Riccardo Patrese. At once James would gesture for the microphone and pour out invective and bile on poor Patrese, whom he always held responsible for Ronnie Peterson’s fatal accident at Monza in 1978. He wasn’t short of an opinion on anything: one year we were commentating on the South African Grand Prix from TV Centre, watching the off-air pictures, although of course we were careful to give the impression that we were at Kyalami without actually saying so. Suddenly, mid-race, James starts banging on about the evils of apartheid, about which he had very violent views. Mark Wilkin, the producer, put a piece of paper under his nose on which he’d scrawled: ‘Talk about the race.’ Anyway,’ said James, ‘thank God we’re not there.’

“His trademark was always to turn up at the last possible minute, but at Spa in 1988 he didn’t turn up at all. Come the warm-up lap, where the hell is James? The race starts, where the bloody hell is James? We put out a story that he was back in the hotel, in bed with food poisoning. In fact he was back in the hotel, in bed with a couple of Belgian nurses. Allegedly.

“I worked with James for 13 years, and it’s a tribute to both of us that we stuck it out. I don’t want you to think I hated James, because you couldn’t hate him. There was a lovely man inside, and when he fell on hard times the nice bloke took over. We were never best mates, but we did grow to like and respect each other. That’s why it was so dreadfully sad when the heart attack took him, aged only 45. Not long before he died, I remember sitting down to dinner with him at Imola, and I asked what he’d like to drink. ‘Orange juice, thanks, Murray.’ ‘Orange juice? What happened to the wine?’ And he said, ‘I think I’ve had my share now.’

I’ve worked with a lot of co commentators: Graham Hill, Barry Sheene, Jonathan Palmer. Working with Martin Brundle was a different kettle of fish. Martin is the best bloke I ever worked with. He’s driven for eight F1 teams, been on the podium, won Le Mans, been World Sports Car Champion. He knows what he’s talking about, knows just how to say it, and he’s got a great sense of humour. With him I never had any problem. It was him that had a problem with me. I shudder now, looking back, because when the race started I was so obsessed with what was going on that Martin used to say, ‘I could have walked out of the commentary box and Murray wouldn’t have noticed.’

“Conditions for broadcasters have improved beyond all recognition and, like virtually everything else in F1, that’s Bernie’s doing. Yes, he’s doing it for very good financial reasons, but when I look at tapes of our early days, the pictures and coverage are just archaic. Now you’ve got all the telemetry the teams have got, fantastic graphics, pitlane reporters, an hour’s preview before the race, summaries afterwards. Unbelievable when you think how far we’ve come, and it’s all down to Bernie.

Murray disliked Senna’s on-track ruthlessness, but had a soft spot for Mansell

Motorsport Images

“Any contact I’ve had with Bernie has always been extremely friendly. Of course he’s a hard man, probably a ruthless man, but I’ve never had any business dealings with him. The last thing I’d like to have to do is negotiate with Bernie. I’d walk into the room fully clothed and walk out naked. But from a historical perspective, I put him and Enzo Ferrari in the same bracket at the top of motor sport, and if I had to choose between them I’d plump for Bernie, because he has made the sport what it is today. In 2001 he said, ‘You’re not really stopping, are you?’ I told him I was, and he said, ‘You’ve got a good 10 years left in you — and I want ’em.’ He proposed I join his FOM TV operation. But I had to tell him, politely, that I didn’t want to do it.

“I did interview Enzo Ferrari: an incredible personality. I was taken into his office and he was sitting there, wearing his dark glasses, with the portrait of his dead son Dino on the wall and, on the desk, the black glass Prancing Horse that Paul Newman had given him. I knew I had to say something to make him take me seriously, so I said, ‘Mr Ferrari, you don’t know me, but you knew my father.’ Not many people realise that Ferrari had a motorcycle team in the 1930s, using Rudge Whitworth bikes, when my dad was sales and competition director there. That broke the ice. I won’t pretend it was the greatest interview I’d ever done — we spoke through an interpreter — but he answered all my questions with immense authority. You knew you were in the presence of a great man. He said that, of all the drivers who’d driven for him, Peter Collins was his favourite. And he said he always regretted that Stirling Moss never drove for Ferrari in F1 — which he was going to do, in a blue-painted Rob Walker 156 in 1962, but of course the Easter Monday Goodwood crash put paid to all that.

“Fangio I saw race many times in the 1950s, but I didn’t meet him until much later. I had this image of a shy, uncommunicative bloke with a squeaky voice who spoke no English, so I was worried about how our interview would go. I couldn’t have been more wrong. He was a very nice man with no side, no boastfulness, perfectly straightforward. We talked about his early days racing in South America, and of course we talked about the 1957 German Grand Prix. He had total recall — what line he took on every corner, what revs he was pulling in each gear, precisely where he was able to make up ground on Hawthorn and Collins, how he passed them. He said, ‘It took me two weeks to recover from the stress and effort of that race. I had never driven like that before, and I never did again.’

“People are always asking me who was the greatest, and there’s no answer to that, because there’s no yardstick to no to compare Fangio with Senna, or Clark with Schumacher. My subjective hero is Tazio Nuvolari. His record with bikes and cars is incredible. And such a charismatic personality. That man had charisma literally oozing out of the roots of his hair.

“I don’t think Ayrton Senna is the greatest racing driver of all time. I’d known him since Formula Ford and F3, when he had those great battles with Martin Brundle. He was the most intense and deep-thinking man I ever met. In an interview you’d ask a question, and he’d sit for about half a minute, and you’d think, ‘Have I lost him? Is he on another planet?’ and then he’d come out with a carefully-thought answer that covered every aspect of the question you’d asked. But I could not respect him for the ruthlessness with which he drove. I know they’re in it to win, and the man that finishes second is, to quote Ron Dennis, the first of the losers. But I think Senna took it too far — like with Prost in Japan in 1990, for example. He was the instigator of a way of driving that has become the norm in F1 today: get to the front at all costs and stay there. Schumacher is the same. It’s easy for me to say. I’ve never raced a car in my life. But I think it’s ethically wrong.

“I started on F1 the year Mario Andretti became World Champion for Lotus, and he was a lovely man, a wonderful communicator with some fantastic one-liners. Eddie Irvine I never got on with, simply because he was unpredictable. You never knew whether he was going to be courteous or bloody rude. Keke Rosberg was a great personality. He collared me in Australia before his final GP, Adelaide 1986, and said: ‘Murray, this is my last race, and I really want to win it. So if I’m doing well, for Christ’s sake don’t say anything about it and jinx me.’ Well, he took the lead, so I had to describe it — and near the end he went out with a puncture.

Murray rates Damon Hill as a better driver than Graham

Motorsport Images

“Damon Hill and Graham Hill couldn’t have been more different. Graham was a hard worker, a great storyteller, life and soul of the party, drop his trousers at the drop of a hat. Damon was equally hard-grafting throughout his career, but could be introverted and withdrawn. But, subjectively, a better driver, and a nicer bloke. Damon has done so much for the BRDC since he retired. As president he could easily have been just an ineffective figurehead, but he’s turned out to be a great leader, and now we’ve got the British Grand Prix guaranteed for the next 17 years.

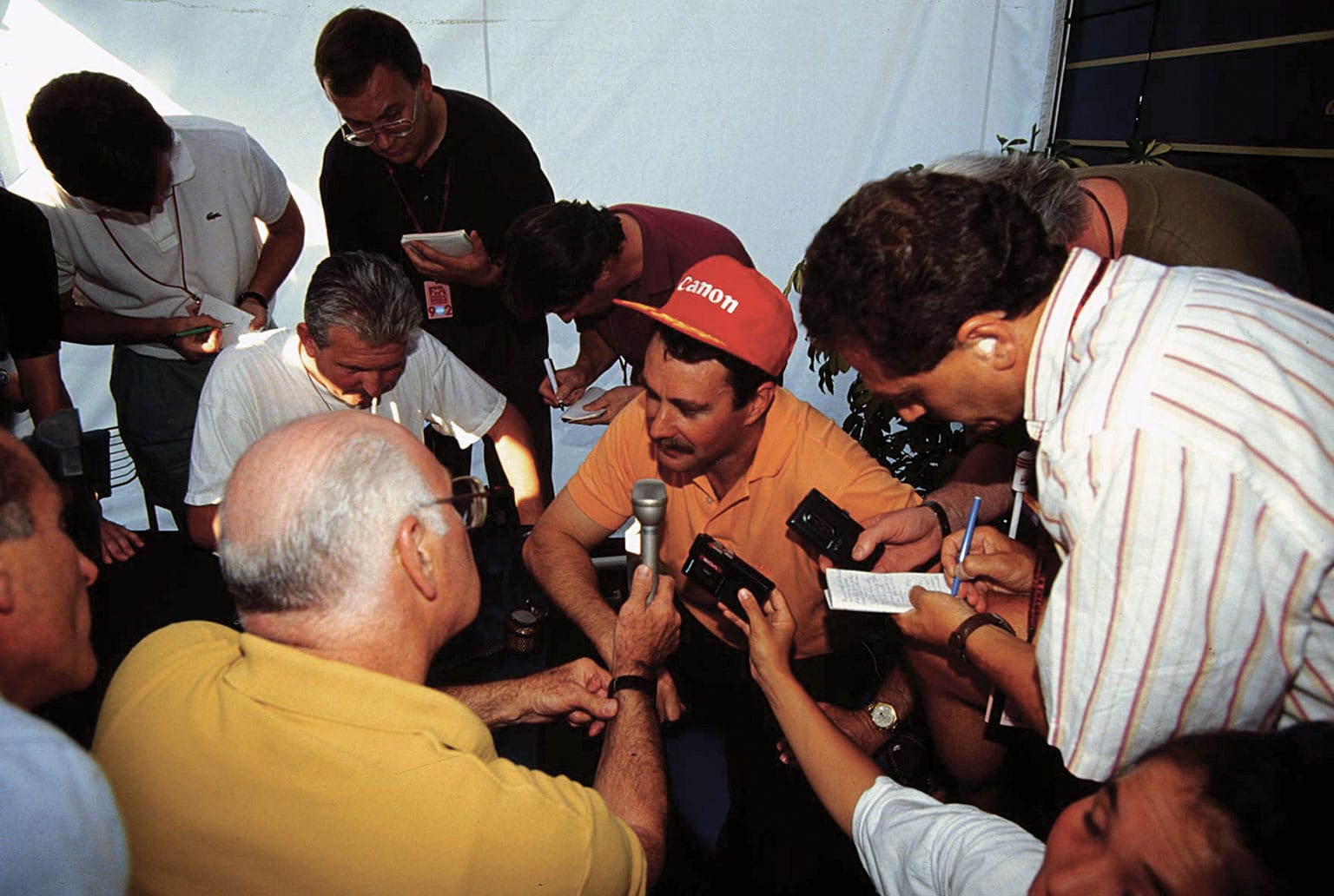

“Ken Tyrrell was one of the most outstanding people it’s ever been my privilege to meet. People like Ken don’t exist in F1 any more, and never will again. How he beat Ferrari, beat the world, working out of a woodyard in Ockham is beyond me. Because I was with the BBC he seemed to regard me as the fount of all knowledge about worldwide sport, and particularly cricket, about which I know literally nothing. I’d be walking across the paddock and this great stentorian bellow would ring out, ‘What’s the score, Murray?’ I’d say in bewilderment, ‘What score ?”The West Indies, you pillock.’