“What’s the problem?” I asked, puzzled. “He never completes a sentence,” she sobbed. “I have no idea what he’s talking about…” I listened to a tape I was working on and realised she was right. I had been automatically finishing sentences for him, the way I did with Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme when I used to write their columns.

Seven days after agreeing to do the book I was back in London with the completed manuscript. The deal had been one-third payment on signing the contract, one-third on delivery of the manuscript and the final payment on the publisher’s acceptance. The book was completed so quickly that I received all the money while my solicitor was still trying to unravel the contract. I told him not to bother. Then the problems arose.

David Benson of the Daily Express had written an instant paperback on Hunt’s title season and ‘our’ publisher panicked. They took the decision not to go head-to-head against the other book, which had the newspaper’s backing, even though our book was by the champion himself. I had a funereal phone call from the publisher to say that they were desperately sorry, but they were delaying publication until the following year. I was on a lump-sum deal without royalties, so it really wasn’t my problem. I’d done my bit. The book was now their problem.

Early in the new year I had a call from Peter Hunt, James’s brother and manager, saying that the book now had a new publisher and they wanted three more chapters to update it — a chapter on James’s early life and one after the Argentine and Brazilian Grands Prix. No problem, I said, £1500 for each chapter and I’m your man.

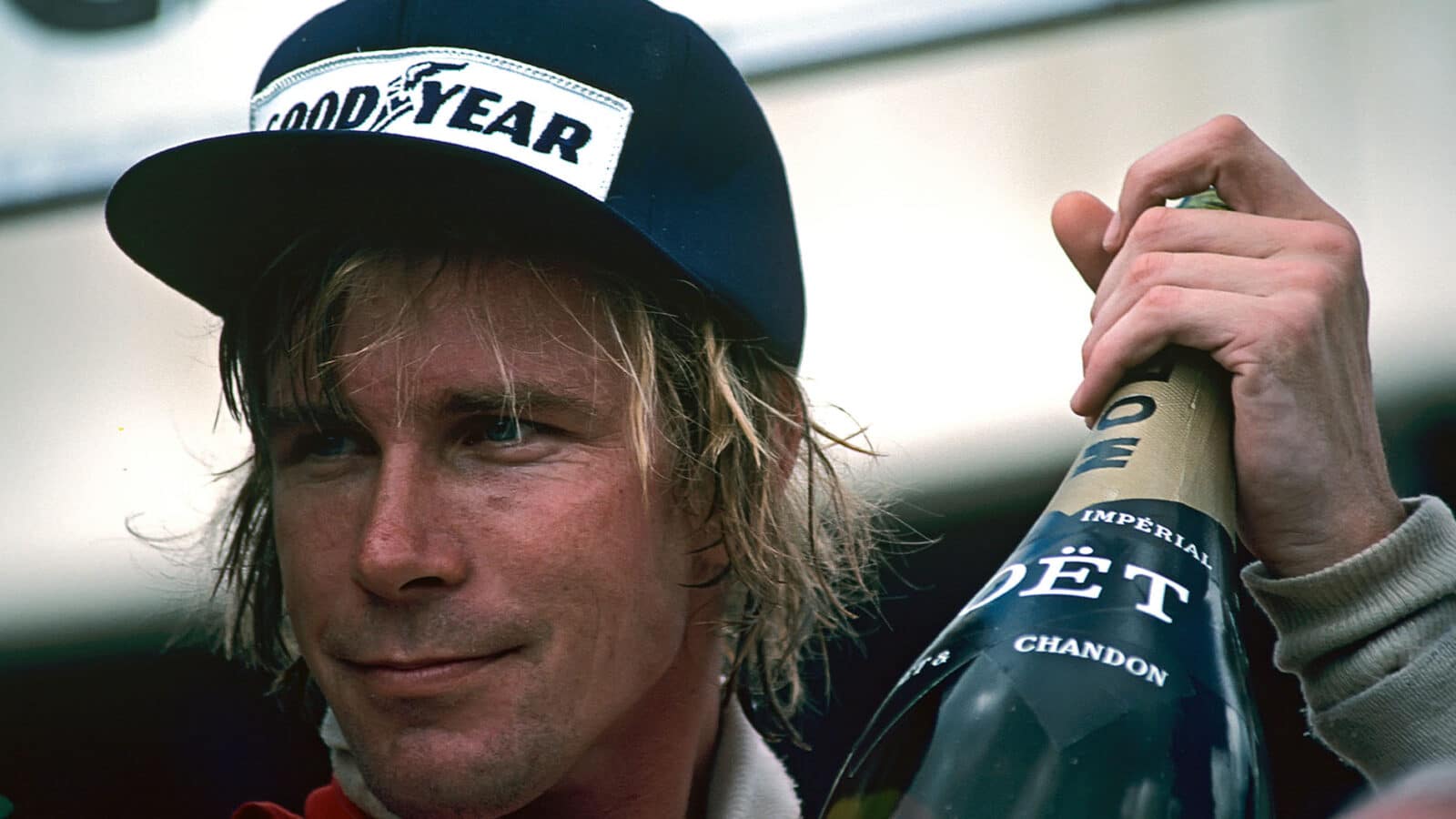

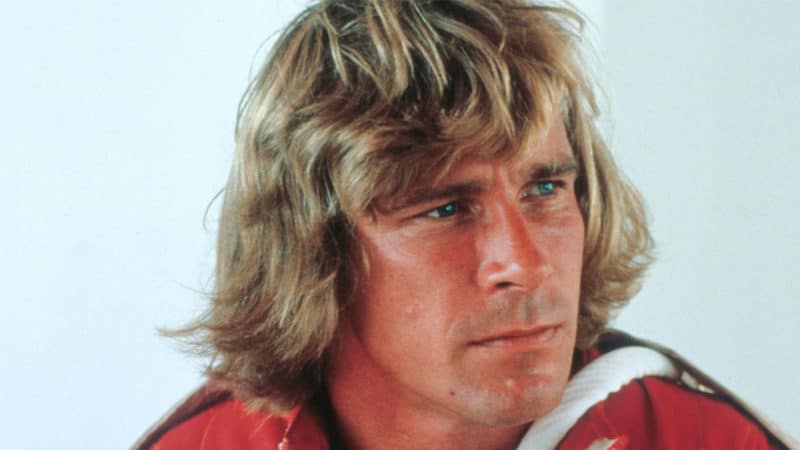

Young began to see a different side to Hunt after spending time with him

McLaren

There was a pause. Peter said, “Eoin, I’m afraid your contract commits you to supplying copy to publisher’s acceptance and the publisher wants three more chapters.”

I asked if he had a copy of the contract with my signature on it, and I could hear him rustling through files. “I think my copy must be a working copy. It doesn’t have any signatures on it,” he said. I told him that if he could find a copy of the contract with my signature on it I’d be happy to do the final three chapters for nothing, knowing full well that he wouldn’t because I had never signed the contract in the first place. I’d just written the book in record time before the contract had been cleared with my legal man. At my suggestion, and with James’s agreement, the book was titled Against All Odds and the extra chapters were written by David Hodges.

Working with James on the book I’d been able to see the other side of him, a serious side if there was such a thing, or at least a different side from the one he displayed when he was “showing off”, as my mother used to put it if I was misbehaving at home in the colonies.