Lunch With... Derek Warwick

He never earned the Grand Prix wins he deserved, but the man once dubbed Britain’s next World Champion isn’t worried. He loves life just as it is.

James Mitchell

Twenty-five years ago Formula 1 drivers had already become, in their own eyes at least, pretty important people. Now they had motorhomes to hide in, and even a chat over a coffee had to be booked in advance via a stern PA, whose job it was to protect her man from unnecessary distractions. But Derek Warwick was never a man to be overwhelmed by a sense of his own importance. In his 11 seasons in F1, when he saw one of the British press in the paddock he’d usually come over, put his arm around his shoulders and say, “Hello, mate” in the Hampshire burr that was an essential part of his down-to-earth, all-embracing friendliness.

In the early ’80s Derek Warwick was Britain’s rising star. While he was still grappling with the unloved Toleman – a car variously known as The Pig because of its lumbering handling, and as The Belgrano (after the sunken Falklands War battleship) because it leaked oil everywhere – no less a person than Nigel Roebuck wrote: “Warwick shows more potential than any British driver since Jackie Stewart. Without doubt he is a future World Champion.”

He did win world titles. In a career that started as a schoolboy and, one way and another, lasted 30 years, he was crowned in disciplines as widely varied as stock cars and Group C. But not in Formula 1. He led Grands Prix, but he never won one. The history books pigeonhole him as a hugely talented driver who simply made bad career decisions, and was always in the wrong car at the wrong time.

Today, Derek doesn’t deny that glib verdict, but he doesn’t lose any sleep over it. For 25 years he has lived on Jersey, presiding over a business empire that now includes domestic and office property, construction companies and car dealerships. On a lofty crag overlooking the sea he has built a magnificent high-tech house for himself and Rhonda, his wife of 30-plus years. It boasts as many bathrooms as bedrooms, a sweeping walnut staircase, a swimming pool terrace, a cinema, billiard room, gym and sauna. In his study the pictures on the walls are not of his own racing exploits, but of his sporting heroes – Federer, Calzaghe, Phil Taylor, Sugar Ray Leonard. He’s 55 now, and the work ethic still drives him: he’s at his desk at Derek Warwick Honda at 7 o’clock every morning. And the cheerful, unassuming character we knew in F1 has endured, unchanged and unspoiled.

At the Oyster Box, a smart place on the curving sandy beach of St Brelade’s Bay, he chooses local line-caught bass with slow-roast pumpkin, and a light Pinot Grigio. “I owe everything to my dad and my Uncle Stan. They shaped the way I am. They were sons of a lorry driver, and started a business in Alresford, near Southampton, making trailers. It was like having two very different fathers. Dad was conservative, normal, worked 12 hours a day, did everything for his family. Stan was a nutter, off the wall, did crazy things all his life. He had five daughters, and I was the son he never had. I was in the workshop from a kid, learned to do everything, repaired the cranes, overhauled the tow trucks.

“I remember when I was 12 bunking off school because we had to put up a farm building in Shepton Mallet. Stan’d pick me up at 5am in his 3.4 Jag and then climb in the back and go to sleep. I’d slide the seat forward so I could reach the pedals and drive the Jag 80 miles to Shepton. Then we’d work there all day. Another time Dad and I were doing a roof and we ran out of hook bolts, so Dad phoned Stan and said, ‘Can you fetch us some up?’ Stan had a little plane then, so he flew up with a couple of big heavy bags of hook bolts. He flew over low, threw the first one out, and it landed on the grass just by the building, perfect. Then he tried to chuck out the second, and somehow it got lodged on the wing. He came over waggling the wings to try to shift it, and finally it dropped – straight through the greenhouse of an off-duty policeman. Demolished the greenhouse, got Stan in the papers, and got him banned from flying for six months. He loved his flying. In 1972 he won the King’s Cup Air Race against all the rich toffs in their Spitfires, collected his trophy from Prince Philip.

“Dad and Uncle Stan reckoned stock car racing looked fun, so they got into Superstox, single-seater things with wings. I went along as mechanic. I started karting at 12, but it cost too much, so I found an old MG Magnette saloon and took it stock car racing, smash bang wallop, on cinder tracks like Wimbledon and Tarmac ovals like White City. When I was 16 I moved into Superstox, racing against Dad and Stan. I was up against big tough scrap dealers, they’d climb out after a race and start fights. I was about four foot nothing then, so I wasn’t built for fights. I’d come in after causing mayhem on the track, and I’d stay in the car while Dad and Uncle Stan would be beating them off, people jumping over the bonnet, all sorts of stuff kicking off. Then it would calm down and I’d get out of the car and get ready for the next race.

“But I wasn’t winning, because the established guys would thump me on the final corner and spin me round. They’d win and I’d get nothing. At Aldershot the top dog put me off again. I backed out of the barrier, waited until he came round on his lap of honour holding the chequered flag, and charged him full in the side, barrel-rolled him over the fence onto the dog track. I was banned for three months, but when I came back I had respect and everybody left me alone. At 17 I became the youngest-ever English Champion. Part of my prize was a tour of South Africa, and I raced there for four months.

“My ambition was to be World Champion, not in F1 – I didn’t know what F1 was – but in stock cars. Got that when I was 19, clinched it at Wimbledon in 1973. Uncle Stan was flying his plane out of Thruxton, and he said, ‘These little circuit cars are fantastic, boy. You need to come and have a look.’ So I did, and I was blown away. Lovely little cars, neat suspension, little gearbox hanging off the back, compared to a stock car a Formula Ford looked like a Ferrari. I thought, I’ve got to have a bite of this. So Uncle Stan and I went up to the Racing Car Show, talked to David Lazenby about a Hawke. Went home and told Dad, but he wanted nothing to do with it, and we couldn’t buy anything without Dad’s approval. I kept nagging him until finally he came up to Olympia with us. He was persuaded, and we went Formula Ford.”

That first season, 1975, was a steep learning curve. “We knew nothing. I’d never had to change gear in a race – in a stock car it’s all in one gear. But it must have gone OK [he won three races] because for 1976 Hawke gave us a DL15 chassis, and we got a free engine, but had to pay for the spare. Everybody thinks their time in Formula Ford was the classic period, but 1976 was pretty special: Derek Daly, David Kennedy, Bernard Devaney, Trevor van Rooyen, John Bright, Jim Walsh, 11 or 12 cars all going into the last corner on the last lap together.” Making trailers Monday to Friday and preparing the Hawke at night, Derek did an incredible 63 races that year. He won 31, with 28 poles and 27 fastest laps. “I stretched myself too thin. I wanted to win everything. There were six different FF series: halfway through the season I was leading three of them and I was second in three. In the end I won the European Championship, I was second in the British and two others, third and fifth in the other two. So I fell short of my aspirations.” But he did get a Grovewood Award, along with F3 heroes Tiff Needell and Rupert Keegan.

This storming drive for Toleman in the 1982 British GP ended when the fuel ran out

Motorsport Images

“There was no way we could go to the next step, F3. Then in December we had an enquiry from Saudi Arabia for six flatbed trailers. Stan said, ‘We can’t do it, we’ve got too many orders already,’ but Dad said, ‘Well, we’ve got to quote.’ To build those trailers cost £700 apiece. So we put in a mad quote, £21,000 for the six – and got the order. We had a family conference, and decided we’d build them after working hours, nights and weekends, and use the profit – something like £16,000 – to go F3. If that order hadn’t come up, my life would have turned out very different.”

In his first F3 season he scored a string of seconds but no wins, but in 1978 he won five of the first six races. Then Robin Herd persuaded him to swap his Ralt chassis for a March. “My mechanics were just two mates who came along, a carpenter and a diesel fitter. They didn’t even know how to change gear ratios, so if the wind changed between practice and the race I had to strip the gearbox myself. We lost momentum trying to get the March sorted, and Nelson Piquet, who had a professional operation behind him, started beating me.” In the end Warwick won the Vandervell Championship, with Piquet second, and Piquet won the BP, with Warwick second. “When we’d sold everything and paid all the bills, that year cost us £17,500. I think Nelson spent £68,000.”

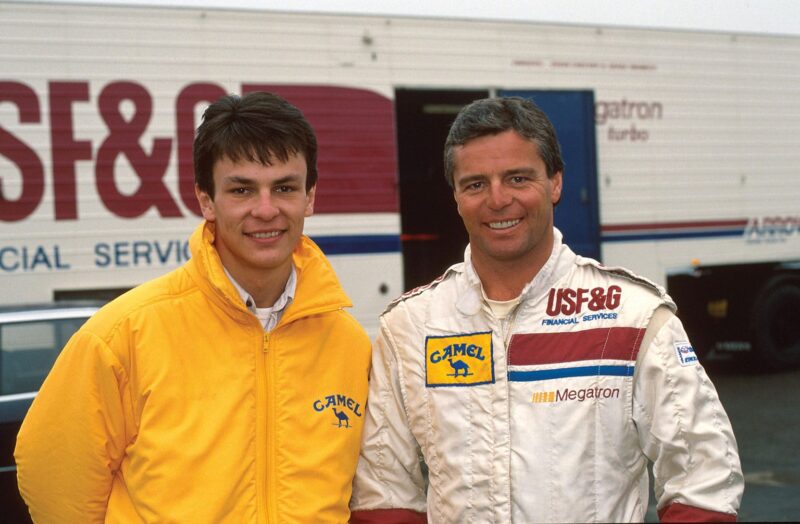

With TWR and Arrows team-mate Cheever. “I love Eddie to death. We’re the best of enemies”

Motorsport Images

In 1979 Derek scraped together an underfunded Formula 2 programme with Jack Kallay’s March. “We were only once in the points, at Mugello, and it looked as though I was finished. The best F2 team was Toleman: they had Rory Byrne, and for 1980 they were making their own chassis, backed by BP. Just before Christmas they summoned me and told me their two drivers were Stephen South and me. For the first time I felt like a professional racing driver, even though they only paid my expenses. Then in February Stephen tested an F1 McLaren without telling [Toleman team manager] Alex Hawkridge. Alex got the hump and fired him, and brought Brian Henton back in. Stephen did drive a McLaren at Long Beach, standing in for the injured Alain Prost, but he didn’t qualify. Then he had a terrible accident in a Paul Newman Can-Am Lola. He lost a leg, and his career was over.”

Toleman dominated the 1980 season, the experienced Henton emerging F2 champion with Derek a close runner-up. “Brian was hard, astute and very streetwise. He taught me that to survive you’ve got to make everything work your way. Pat Symonds engineered his car, and I had John Gentry, who was great. Then Jackie Oliver summoned me to Montréal to stand in for the injured Jochen Mass at Arrows. I was really excited to be making my F1 debut. I was just getting in the car when Jackie put a piece of paper in front of me and said, ‘Sign this.’ It was a contract binding me to him for the next five years. I told him I couldn’t sign it, because Toleman was going F1 the next season with a turbocharged car. ‘Turbos,’ said Jackie, ‘are a disaster. You’ll never get anywhere with a turbo.’ He got really aggressive, wouldn’t let me in the car unless I signed. I didn’t have a 1981 contract yet with Toleman, but I wanted to stay loyal to them, so I asked Alan Rees, Jackie’s partner at Arrows, what I should do. Dour little Reesie, straight to the point, said, ‘You should tell Jackie to f**k off.’ So I did. Seven years later I was driving for Jackie in F1 – in a turbo.”

First season with Toleman, as runner-up in European F2

Motorsport Images

The next year Toleman did make its brave foray into F1, the first turbo team after Renault and Ferrari, using the Hart four-cylinder. “It was a nightmare. The car was impossible to drive, the engines kept blowing up, the team was under-financed, and we were on Pirelli tyres. We weren’t just slow: we were seven seconds a lap off the back row. Jackie Oliver bet me £25,000 I wouldn’t qualify for a single race that year – and in the final round, at Las Vegas, I got it on the grid. Kept going for 42 laps in the race, too, until the gearbox broke. Because of finance we had to keep the same car in 1982, with Teo Fabi as my team-mate, and I finished a couple of races, but it still wasn’t much good.”

Which made Derek’s performance in the 1982 British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch all the more sensational. Having qualified 16th, he stormed up the field, passing car after car until he took second place from Didier Pironi’s Ferrari around the outside of Paddock Bend, and pulled away. “The crowd went mad. I could hear them from inside the car. But the truth was we were about to lose our sponsors, Candy, and we were desperate to put on a good show. So we did something that Gordon Murray at Brabham picked up and developed to a much higher level. We started on half tanks, so the car was running very light. There I was, second, listening for the chug-chug that would tell me I was running out of fuel. Sure enough, after 40 laps, I heard it. We told everybody a driveshaft had gone.

“Including F2 I was four years at Toleman. I believed in them. Rory Byrne, John Gentry my engineer – he’s godfather to one of my daughters – and Brian Hart, they were true racers. Brian never had the budget to demonstrate his talent, but he was really respected by other engine people, men like Paul Rosche of BMW. Ted Toleman owned the team, but Alex drove it forward, found the few sponsors we had. I know he was a controversial figure because of the stuff in the News of the World about his private life. But as far as I was concerned he wasn’t the person the tabloids portrayed.

“For 1983 Rory came up with that twin-wing car, the TG183B. It was still unreliable: for cost reasons we were using a Garrett turbo off a Magirus truck, and they kept breaking. Then we switched to a Holset turbo, and at once it came right. At Zandvoort we qualified seventh and finished fourth. Toleman’s first points. After the race Jenks and Roebuck were almost in tears. Everybody loved the underdog thing about Toleman. And we finished in the points in all the other races that year.”

On winning form in F3 Ralt in 1978

Motorsport Images

Derek’s efforts to develop an uncompetitive turbo car had not gone unnoticed, and Renault needed to replace Alain Prost. “Suddenly I was talking to proper people with proper budgets. At Toleman I’d earned £30,000 in 1981, rising to £50,000 by 1983. Renault were talking figures out of Christmas crackers. My sign-on fee was half a million dollars, with overalls and personal sponsors down to me. That first Renault year my total earnings were close to $2 million – and this was more than 25 years ago. They had a great set-up: Michel Tetu as designer, Jean-Claude Migeot doing the aerodynamics, Gérard Larrousse and Jean Sage running the team. Patrick Tambay was the straightest team-mate I ever had. If he said rear dampers up two clicks, you’d know he’d done his rear dampers up two clicks. You couldn’t say that of most of my other team-mates.

“First race with Renault, in Brazil, I qualified third, and by lap 39 I was in front. I had a big lead over Prost’s McLaren, but I’d had a brush with Niki Lauda’s McLaren, which bent the front suspension, and with 10 laps to go it broke. I was gutted. Third at Kyalami, second at Zolder, but the McLarens were dominating now. After I was second at Brands Hatch, Sage put me under a lot of pressure to re-sign. Frank Williams made me an offer for 1985, but after a lot of heartache I decided to stay with Renault. So Frank signed Nigel Mansell instead. Of course I could say, ‘If I’d gone to Williams instead of Nigel maybe I’d have been World Champion.’ But I don’t think like that.

“And in 1985 Renault bombed. Tetu left, and the heart went out of the team. A guy called Gérard Toth came in from the production side of Renault, and he thought he could reinvent the wheel. The car was a disaster. In the first test in Brazil we were 3.5sec slower than with the old car. That year my career took a massive hit. But I never thought, I wish I was driving a Williams now. I just thought about making the car better, working at it.

“At the end of that year Renault pulled out, but Lotus came to me with a contract to run alongside Ayrton Senna, replacing Elio de Angelis who’d gone to Brabham. When Senna heard about it, he blocked me. He thought of me as a front-runner, and he used all his considerable power with JPS and the other sponsors to get rid of me. From his point of view he was right, because he wanted to put himself in the best position, and Lotus didn’t have the set-up to run two front-running cars like McLaren or Ferrari. I had two months in limbo. Peter Warr didn’t confirm to me that the contract was withdrawn until mid-January, and by then there was nothing out there. Lotus signed Johnny Dumfries, who was acceptable to Senna. Ayrton got slated in the press, but he sent me a card wishing me all the best for 1986. I don’t think he was taking the mickey, I think he meant it. I could bear malice, but life’s too short. In 1994 I was among the drivers who went to his funeral in Brazil, and in my study, among the other great sporting champions, Senna’s picture is on the wall.

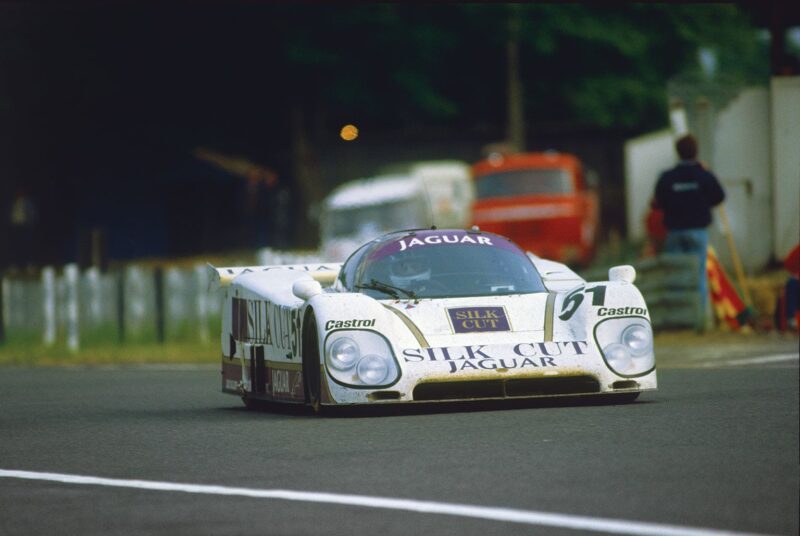

Then Tom Walkinshaw came after me, signed me as official number one for the Silk Cut Jaguars. I went to St Moritz for fitness training and met my team-mates. We’re all sharing one room, and Eddie Cheever and Jean-Louis Schlesser think it’s very funny to hide my bed in a cupboard. We go down to the sauna and, to wind Eddie up, I say, ‘I’m surprised you signed for Jaguar, being my number two and all, but I guess you needed a drive.’ He jumps up: ‘Whaddya mean? Tom signed me as number one. It’s in my contract!’ There we are, naked in the sauna, arguing. We both grab towels, rush up to our room and get our contracts. Typical Tom – he’d told both of us we were No 1.

1992 brought better results – victory at Le Mans in a Pugeot 905 with Blundell and Dalmas, and the drivers’ title

Peugeot Sport

“We had a good year, Eddie and I, we won Silverstone, and I missed the drivers’ title by one point. I’d done Le Mans before, in a Kremer Porsche in 1983, but I’d never experienced anything like the pre-race drivers’ parade, coming to the grid in a Jaguar with the emotion rolling off the Brits in the crowd, cheering and waving their flags. Then Elio de Angelis was killed testing for Brabham at Paul Ricard. At once friends in F1 called me, saying, ‘This could be an opening for you, Derek.’ I said, ‘Hang on a minute, it’s only just happened, give the guy some respect.’ And I deliberately didn’t ring Bernie Ecclestone. I reckoned if he wanted me he’d find me. When he did, he said, ‘Why haven’t you called me up like all the other w**kers? You’d better come and see me.’

“By the time I got there I’d convinced myself I was worth millions, I’d be the saviour of the team. But this was my first experience with the master poker player. He wouldn’t let me past his office into the factory until I’d signed. He offered me Elio’s contract, less the races that had already happened. I launched into my spiel, and he jabbed me in the chest with his finger and said, ‘You’re not listening. This is the deal.’ So I signed. In the race shop the mechanics were giving me the thumbs up, then suddenly they all dived down into the cars and started making themselves very busy. I turned round and Bernie had steam coming out of his ears. Somebody had hung up the receiver on a wall-phone with the wire twisted. Big no-no. He put one foot against the wall and tore out the phone, threw it on the floor in a heap of dust and plaster and strode out, leaving me there dumbfounded.

“Bernie was a total perfectionist. He had the pockets sewn up in the mechanics’ overalls so they couldn’t have rags or spanners hanging out. The vertical blinds in the windows were fixed immovably at exactly 45 degrees. When we’d get to a circuit for a Grand Prix I’d ride round with Bernie to take a look at everything, and he’d bark out orders to his oppos: ‘Get rid of that banner. Move that hoarding two feet to the right. Get those flags level.’ He’s an incredible guy. Dad and Stan were petrified of him. When I was with Brabham they’d stand at the back of the pit and not move a muscle.

Turbo motor proved too much for Brabham in 1986

Motorsport Images

“That was the year of the low-line Brabham BT55. It looked fantastic, but structurally it wasn’t stiff enough, and there were oil scavenge problems with the engine lying on its side. At my first test I was in the front of the truck with Riccardo Patrese and Gordon Murray, and I said, ‘I’m sorry, Gordon, but it’s shite. Unless we do something fundamental it’s going to be a dog all year.’ The door opens and Bernie sticks his head in, says to me, ‘’Ow’s it going?’ ‘Fine, Bernie.’ ‘’Ow’s the car?’ ‘It’s fine, Bernie.’ ‘Why you so f**kin’ slow, then?’

“The power of that turbo was something else. At Monza they blanked off the wastegate and I qualified it with 1350 horsepower. It had a seven-speed gearbox, and under acceleration I couldn’t change gear fast enough. It was ripping the tyres, ripping the gearbox, ripping my neck, ripping everything. The qualifiers would last one lap. I remember getting as far as the Parabolica, really excited because this was going to be such a quick lap, and BOOM. It blew up so comprehensively they couldn’t take the gearbox off the engine. They just threw it away as one melted lump.

“For the rest of 1986 I was doing F1 and sports cars together, racing somewhere in the world every weekend. For 1987 I signed for Arrows, had three tough years there. I like Jackie Oliver a lot. He’s never really had the credit for keeping Arrows going for so long. He’s very intelligent, very focused, but not really a people person. If he thinks somebody’s a fool he’ll tell him. In ’87 and ’88 the car wasn’t particularly good, but by 1989, when we went normally-aspirated, Ross Brawn did us a really good car. Ross had a different way of going racing. He could get the best out of everything and everybody around him, drivers included. We qualified sixth at Monaco, and in Canada, in the rain, I led – until the engine blew.

“And all my time at Arrows there was Cheever, my team-mate again. I love Eddie to death. We’re the best of enemies. Our biggest bust-up was in 1989, at Monaco. In qualifying I was on a fantastic lap and he deliberately baulked me. I still qualified sixth, that’s how good the car was there, but I got annoyed and I put him in the barrier. Back in the pits I’m getting out of the car and there’s Eddie clambering over everything, coming for me. Ross and the mechanics had to separate us. For two races he refused to talk to me, wouldn’t even debrief with me. Then at Phoenix, in the hotel, we happen to get into the lift together. He stands beside me with his back turned. I say, ‘Eddie, this is getting ridiculous. I’ve never seen anything so childish.’ He turns round, grins, says, ‘You’re right,’ and we were fine after that. Eddie’s a one-off.

“Jackie offered me good money to stay for a fourth year, but for 1990 I signed for Lotus, which again was a massive mistake. Lamborghini V12, Frank Dernie, Mike Coughlan, Rupert Manwaring as team manager, not enough budget. I should have known what I was in for after the pre-season launch. I was meant to drive the car into the marquee where the press were waiting, but as I drove it out of the garage the gearbox began to fall off. The guys put clamps everywhere and pushed me into the tent with me blipping the throttle.

Carrying British hopes at Le Mans that year with Jaguar

Motorsport Images

“I scored a few points here and there, and then at Monza I’d qualified 12th and we were coming into the Parabolica in the lap one traffic jam. I got too close to Mauricio Gugelmin, lost downforce and understeered off into the barriers. That took off the left-hand wheels, and then I barrel-rolled. It carried on down the track on its back in showers of sparks, my helmet bouncing on the road. I’d already turned off the engine and undone the steering wheel because I had 220 litres of fuel on board, there were other cars close behind, and if one of them hit me there’d be fire everywhere. As soon as the car stopped I squeezed out from under, saw the race was being red-flagged and my first thought was, if I can get out in the spare car within 15 minutes I’ll keep my grid position. So I ran to my pit. I remembered my next best set of tyres was Set 11, so I screamed at the mechanics, ‘Set 11, Set 11,’ and clambered into the spare. One of them undid my crash helmet. I shouted at him, ‘I’m all right, nothing wrong with me.’ He said, ‘Derek, you’re helmet’s smashed, you’ve got to change helmets.’ They found my spare helmet, strapped me in and I drove out of the pits. I got to the grid, started to compose myself, and Bernie appeared beside me and said, ‘Out. Go and see Prof.’ So I get out, go to Sid Watkins in the medical car, and Bernie gets in too. Prof says, ‘Derek, I’m going to ask you some simple questions to see if you’re ready to race. What’s your name?’ I say, ‘Nelson Piquet.’ Bernie says, ‘Answer properly or you’re not going to race.’ Prof passed me OK, I got back into the car with the biggest headache in the world, did the race. After 15 laps the clutch went, which was probably just as well. People said I’d been brave, but it wasn’t brave at all.

“Maybe I was brave three weeks later at Jerez. During Friday qualifying my team-mate Martin Donnelly crashed on a quick right-hander when the front suspension broke. I was in the pits and I saw it on the screens. I ran straight there, and when I saw it I thought for sure Martin was dead. The front of the car was gone, the back half was on the grass, and his contorted body was lying in the track, strapped to his seat. That’s when I saw what Prof Watkins was really about. When I’d had accidents he’d always been calm, gentle, but this was urgent. He pulled Martin’s helmet off, turned him over and was beating his chest to get him alive again. Without him Martin would have died right there.

“I knew a breakage caused the accident, I knew the car wasn’t strong. Back at the hotel with Rhonda and Dad, we agreed I shouldn’t race. Next morning I got to the circuit, the mechanics were red-eyed, they’d been working all night to fix titanium plates to the suspension. We heard Martin was critical but alive, and I changed my mind. Rhonda and Dad were really upset with me, but I couldn’t let the mechanics down after all their work. I decided either I was going to do it or not do it, and first time through the corner where Martin had crashed I was on the limit. I qualified that bloody Lotus 10th, 1.5sec quicker than on Friday, and I ran sixth in the race. There were 10 laps to go when the gearbox broke.

With Renault team-mate Tambay (15) at Brands Hatch in 1984. Derek was second to Lauda’s McLaren

Motorsport Images

“At the end of that year I had nothing, I wasn’t on the F1 radar. Then Ross Brawn told me the new Jaguar he’d done for Walkinshaw, the XJR14, was going to be quick and they wanted a British driver. So I signed for Tom again. Good money for sports cars, $1.5 million plus bits and pieces, and the team won the championship. I missed the drivers’ title because I got disqualified from Silverstone after winning it with Martin Brundle. I was down to race with Teo, but his car had a problem so I switched to Martin’s car. As I was getting in I said to Tom, ‘Are you sure this is legal?’ Tom said, ‘You drive the car and leave the team tactics to me.’ I was docked 20 points.

“My brother Paul – he was 14 years younger than me – had worked up through FF and F3 to British Formula 3000, and he was dominating it. I loved my little brother. Of course he looked up to me, but I tell you I looked up to him, because he was something special.” Derek is an emotional man, and now, sitting in the restaurant, his eyes focus on somewhere far distant and fill with tears. “It’s 19 years ago now, but not a day goes by without me thinking of him. Talking about him is still tricky for me. His early career wasn’t so good, but once he got in the faster cars he got better and better. That year he did five rounds of the F3000 series. Five poles, five wins, five fastest laps. I went to watch when I could, but that July weekend, when he was at Oulton Park, I’d just got back from a TWR test at Jerez, and Rhonda persuaded me to stay home for a game of golf.

“All through our game I was phoning Paul’s friend James in the pits. ‘He’s leading, he’s seven seconds in front. Hang on, there’s a red flag. It can’t be him, he’s just gone by.’ I called again: ‘He’s involved, but he’s OK. He’s out of the car.’ Then Dad came on the phone. ‘Get here now.’ My plane was being serviced, but I managed to rent another to take us to Manchester and we took off within minutes. He died while we were in the air. A front wishbone had broken at Knickerbrook, fifth gear, he’d hit the barriers, the car broke in half and he ended up many yards away. They gave him the win, as he’d been leading the lap before the red flag. At the end of the year his points were unbeaten, so he ended up F3000 Champion. The only other posthumous champion I know of was Rindt.

“It was a long journey back to Alresford, knowing we had to face my mum and sisters. Right then I made a promise to my mum that I wouldn’t race again. But she was a good old-fashioned mother, she said, ‘You’re a racing driver. You’ll always be a racing driver.’ I didn’t know what to do, so Tom organised a private test at the A1-Ring in Austria. In the garage all the mechanics bent over their work, doing up imaginary nuts – they didn’t know what to say to me. I was on autopilot. At the end of the day we tried some different rear dampers, and in that very fast kink on the back straight one of the dampers seized and pitched me into a huge spin. I ended up in the gravel trap. I got in my hire car, went back to the hotel, shut myself in my room and bawled my eyes out. During the night I got up, splashed cold water on my face, and said to myself, ‘You’ve got to make a decision, Derek. You can’t mess Jaguar and Walkinshaw and everybody around.’ Next day I went back to the A1-Ring and got under the lap record. Then I went to the next round at the Nürburgring, and won it with David Brabham.

Sole BTCC win at Knockhill in 1998 aboard Triple Eight Vauxhall

Motorsport Images

“For 1992 I switched to Peugeot, master-minded by Jean Todt. I developed huge respect for him. He’ll do a good job as FIA president – remember, he has hands-on experience of running teams in rallying, sports cars and F1. He and Peugeot really accepted me. With Yannick Dalmas I won Silverstone, won Le Mans with Yannick and Mark Blundell, finally got that drivers’ title too. But I still hankered after F1. I was thinking about Indycars, had a test at Mid-Ohio with Jim Hall, then both Eddie Jordan and Jackie Oliver came after me. I signed for Arrows – now called Footwork – because they had Alan Jenkins, and I knew he’d build a good car. I consider myself pretty strong-minded, and 1993 was the only time I let somebody get under my skin. Jenkins didn’t want me in the car, he’d wanted to hang on to Michele Alboreto. He was a good engineer, but he didn’t respect me for what I’d done and could do, and we clashed from day one. Instead of getting the best out of me he got the worst. My last points came with fourth in Hungary, and that was my F1 career.

My business life was very complex now. In 1995 I went British Touring Cars with Alfa, for something to do at weekends. But racing against professionals like Menu, Cleland, Rydell, Tarquini and Will Hoy, bloody quick guys focusing seven days a week, I underestimated the challenge. So Ian Harrison, Roland Dane, John Gentry and I decided to put a BTCC superteam together. That was Triple Eight. We signed with Vauxhall, and at first I drove for the team. I won one race at Knockhill, but running the businesses, trying to manage the team and drive as well just didn’t work. In 2002 Roland and I sold our shares to Ian. He has gone from strength to strength: Triple Eight have won a lot of BTCC titles. We also set up Triple Eight in Australia to run V8 Supercars. Our drivers, Jamie Whincup and Craig Lowndes, are top dogs.” Derek is also a busy director of the BRDC, and has been on the MSA Safety Committee for nearly 20 years. “When I joined in 1991 people said it was just a reaction to my little brother’s death. But I’m still there, and I think we do important work.

With much-missed brother Paul in 1988

Motorsport Images/Sutton

“I’d have liked to win Grands Prix, of course. I could look back and get annoyed with myself for making some bad decisions. But I don’t. All along I never wished I was doing something else, and it’s the same today. I love my wife and family, I love my friends, I love my work. I love every waking moment of my life. I’m all right.”