But Nissan had hardly been idle. Its brand-new R381s were bewinged Group 6 coupés which were supposed to be fitted with a self-built 6-litre V12. The latter unit was not ready in time, however, so 5-litre Chevys prepped by Dean Moon in Los Angeles were fitted instead. This move was indicative of Nissan’s pragmatic approach. Toyota, in contrast, was keener to do as much as possible, chassis and engine, in-house (or with its close ally Yamaha at least), whereas Nissan was happy to use a Lola platform as its base. Toyota steadfastly stated it was going motor racing to learn as much as to win. Which was a good job, because they bombed on their debut. The 7s struggled to keep up with Nissan’s old 2-litre R380s, never mind the R381s, and could do no better than eighth and ninth. There was to be no hiding behind the class win either: Nissan had finished 1-2-4-5-6.

Hiroshi Fushida was Toyota’s ninth-placed driver that day: “The programme was well funded, but we had a lot of catching up to do. The first 7 had a reasonable chassis, but it did not have enough power. And it was quite tiring to drive – even allowing for the fact that all cars back then were quite difficult to drive.”

Matters improved during the rest of that Japanese season, with a brace of wins in 1000-kilometres races, but the real test was to be the World Challenge Cup at Fuji on November 23. This would see the arrival of 10 ‘true’ Can-Am machines. The dominant McLarens of Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme were not among those scheduled to come, but the likes of Mark Donohue and Peter Revson would provide a good benchmark. And as it turned out, they were streets ahead, Revson winning, the best Toyota almost 10 laps adrift in fifth. There was a lot more to do.

Toyota faced an uphill struggle Japanese rivals

Toyota

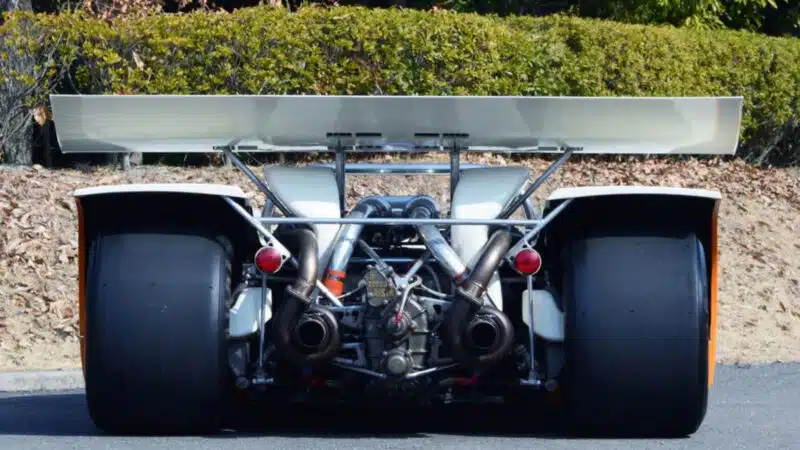

The next evolution of the 7 appeared in mid-1969. With a more angular body hung off an aluminium spaceframe and a 5-litre V8 amidships, it was much more purposeful – but not without fault.

Fushida: “Now we had the power, but perhaps not the chassis.”

As it stood, however, 1969 was not a wipe-out – far from it. Fushida, with Yoshio Ohtsuba as his co-driver, won the Fuji 1000Km – the new car’s debut – but again the season was geared around the Japanese GP in October and the second ‘CanJapAm’ in November.