By this time, however, Bruce-Brown’s mother, alerted by the school to her son’s disappearance, was hot on his trail. She arrived at Daytona to discover that he’d been promoted from millionaire mechanic to millionaire driver and, encouraged by Cedrino, was due to make a competitive run in one of the Fiat racers. The lady threatened to sue the organisers if they let her son compete. But maybe his charm worked once again, because he not only ran, but broke William K Vanderbilt’s one-mile amateur record that had stood since 1904. Sitting alongside him was Scudelari, not long since arrived from Fiat to help Cedrino, and who was making a new life for himself in New York.

Mrs Bruce-Brown was reportedly caught up briefly in the excitement of her son’s achievement, before perhaps realising that he was now a man, immune from her protection and unlikely to take up the place at Yale that had been expected. His mother, a widow and clearly a lady of some spirit, features prominently in this story. As her son – one of two – took leave of his New York society life to contest his next race, so she would depart from the family townhouse at 18 East 70th Street, or the country retreat in Islip, Long Island, and follow him. Once there she would harangue him, threaten to disown him, make him promises of gifts if only he would give up on this crazy, lethal sport. And each time Bruce-Brown would climb into his car and win, and his mother would be flushed with pride and excitement. A psychologist would have found a wealth of material here.

Bruce-Brown followed his Daytona exploits with another amateur class win in the hill climb at Shingle Hill, ironically an event sponsored by Yale University. Emboldened by success and sufficiently wealthy and talented not to bother with lesser machinery, for 1909 he purchased the 1908 Grand Prix Benz with which Richard Hanriot had finished fourth in the American Grand Prize. With this 12.5-litre device he lowered his own record at Daytona and took a flurry of victories in national speed trials and hill climbs.

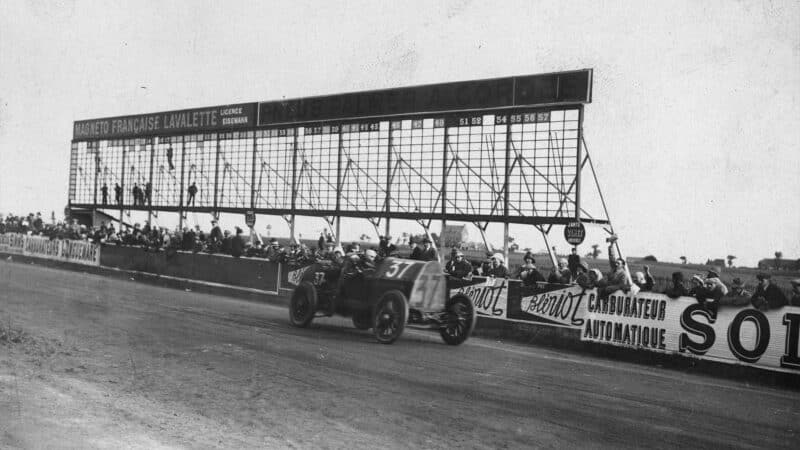

Competing at the 1912 French GP

Getty Images

The Benz team had clearly been impressed by the form of their customer because, for Long Island’s Vanderbilt Cup race of 1910, he was part of its factory line-up. Unfortunately, the team was in complete disarray following the career-ending accident of Bruce-Brown’s team-mate George Robertson during a demo run. So in his first big-time race, Bruce-Brown struggled to 13th after myriad problems. But the main event of 1910 was the American Grand Prize at Savannah, Georgia, a few weeks after the Vanderbilt. This was the most prestigious motor race in the world that year, given the cessation of grand prix racing in Europe at the time. Among the entry were the European factory teams of Fiat and Benz, and one of the 15-litre Benz was earmarked for Bruce-Brown. In this company, he was an unknown quantity, up against legends like Felice Nazzaro, Hémery and Louis Wagner, not to mention the young American superstar de Palma in one of the works Fiats. Alarmed even more than usual, on account of Robertson’s serious accident at Long Island, Bruce-Brown’s mother made the trip to Savannah to plead with her son once more.

It should have been de Palma’s race. His Fiat was in a commanding position with just two of the race’s 24 laps to go when a stone went through its radiator. That left Bruce-Brown in front, ahead of teammate Hérnery. This was the first time he had led the race, but his had been an approach of stealth. Rarely was he out of the top three and, unlike the others, he had got by on just one pitstop – when a fresh right-rear tyre was fitted. It was a spookily mature performance.