The torque from 3700 to 5000rpm is not quite kidney-compressing, but it does shove you firmly into the back of the bucket seat. More impressive still is the car’s composure. Yes, it does require constant minor steering corrections, but that’s necessary from the 40mph mark on and, curiously, gets no worse as the speed rises. In fact, its tall tyres allow it to soak up grooves and ridges more competently than wide-tyred low-profile rubber fitted to 21st-century cars, while the non-period roll-cage prevents bad flexing over the larger crests.

If constantly tweaking the tiller comes as second nature, then so does braking early and lightly, anticipating rather than reacting. If you wait to see the brake lights ahead glow, a Healey grille/Mondeo boot interface is all too likely. And don’t assume, either, that you will be saved by engine braking. Even double declutching won’t guarantee slotting a lower gear in time to be of any use in retardation. Unless, of course, you are a past master. “I felt that we got a reasonable amount of engine braking,” says Donald. “As for the brakes themselves, well, they weren’t bad at all for the day, especially once they got properly warmed up. Mind you, many times at the end of a special stage we would get out and see our brakes were glowing bright red.”

One imagines an Austin Healey 3000, especially in rally spec, to be a brute. The image of a beast lurking beneath the beautiful Gerry Cokerpenned skin is what sold them after all. But it’s an animal of the Whipsnade Zoo variety: the potential to bite is there, but it’s harmless unless cajoled into doing something it oughtn’t Donald confirms this.

Surprisingly roomy cockpit

Richard Newton

“For its day, the Healey handled really very well, and once the Weber carburettors went on in 1962, we had 200bhp with which to throttle-steer the car, and that made us very competitive against the Porsches, for example. The downside was that it was quite heavy on tyres. I remember once on the Alpine Rally wearing out a set of tyres and a set of brake pads in four hours.”

‘I remember once on the Alpine wearing out a set of tyres and brake pads in just four hours’

Today, that docile-if-handled-with-commonsense nature remains, inspiring confidence in the novice driver. Keep a firm hold of the steering wheel and, providing entry speed isn’t overly optimistic, the front will grip amazingly well in the dry, encouraging the driver to get full on the gas ever sooner on successive apexes. The natural limit is found as the front end gets a little light, there is a momentary vagueness in the steering and a touch of understeer, but if you’ve left enough room, it’s nothing troubling.

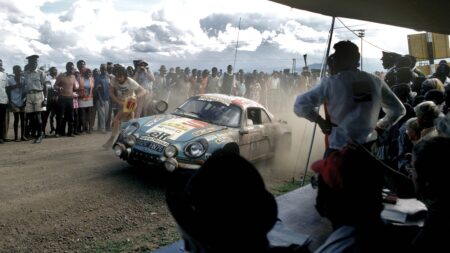

That’s the score on A-and B-roads, at least. Down dusty single-track lanes, a prod of throttle on corner exits can be used to straighten the car out as 190bhp breaks traction. And beyond that are you kidding? Not on blind corners on public roads, not in the dry, and certainly not when the emotional ties between car and owner, Mick Darcey, are so strong.

Says Mick: “After the Morleys rallied it for BMC, Peter Moon ran XJB876 with works support from 1962, which is when the triple SUs were replaced by triple Webers. And then a gentleman called Sid Segal bought it, completing his trio of ex-works Healeys which comprised 67ARX and SMO744. I had a road-going 3000 MkIII at the time, and he befriended me just through that link. When he came to sell them, I was starting my own business, and I couldn’t afford to buy one, let alone the whole trio. So I assumed I had missed my chance. “One Sunday morning, though, I got a call from him to pop over for breakfast That was quite a regular occurrence, only this time he told me to bring my Healey. After breakfast, we walked down to his garage, opened the doors, and there was XJB876. He said, ‘I want you to have it,’ and I replied, Sid, I still can’t afford it’. And he told me to give him my road-going 3000 in exchange, and to forget the difference in value! Sid Segal was one of a kind.” Clearly.