Benoist’s ability was complemented by that of Albert Lory, the ex-Salrnson designer whose supercharged 1.5-litre straight-eight endowed Louis Delage’s low-slung racers with 170bhp at 8000rpm. The only drawback in 1926 was that the exhaust system turned the cockpit into a fume-filled, foot-frying furnace. In 1927, after Lory modified his jewel of an engine, Benoist was proclaimed world champion after winning every race he entered, notably the Grands Prix staged at Montlhery, San Sebastian, Monza and Brooklands.

Delage’s decision to stop racing ended Benoist’s career as a fully fledged works pilot, but those were times when good men could get competitive drives on a relatively casual basis. His later outings included tackling Le Mans in a Chrysler and an Itala, winning the 1929 Spa 24-hour race in an Alfa Romeo, several Grands Prix at the wheel of a Type 59 Bugatti, record-breaking runs at Montlhery and the Le Mans victory, at record-breaking speed, which achieved a great personal ambition as well as ending his career on the highest of notes.

The quest for reliable information about his wartime adventures revealed two enthralling books, Special Operations Executive 1940-46 and SOE in France. Their author, MRD Foot, told me Benoist’s SOE file had survived in the depths of Whitehall. I would not be allowed to examine it myself, he explained, but could ask questions. Much of what follows is based on answers to those questions.

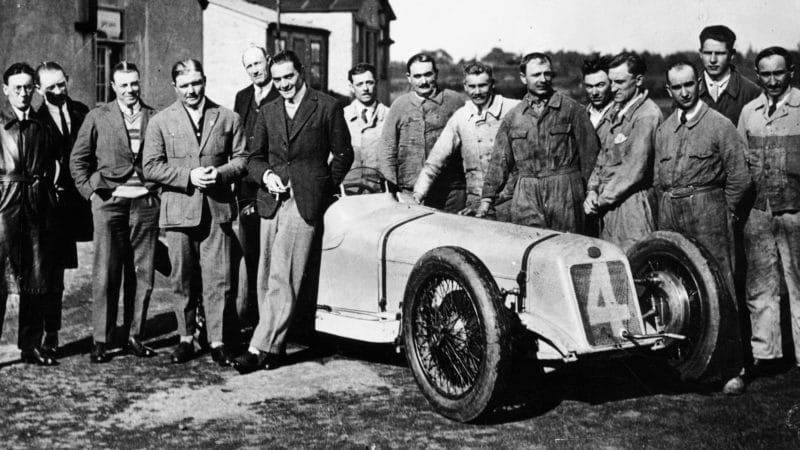

Benoist with mechanic

Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Benoist was working for Bugatti in Paris in September 1939 when Germany invaded Poland detonating the Second World War. He was recalled to the colours but, considered too old to fly, twiddled his thumbs until the eight-month lull before the storm ended. Using blitzkrieg tactics, epitomised by fast moving tanks and screaming dive bombers, Hitler’s spearhead thrust across France in a few days, driving the British Expeditionary Force home from Dunkirk.

Determined to escape, Benoist headed south in a Type 57S Bugatti, and, according to one account, was in Poitiers when his rakish car caught a German officer’s eye and was herded into a convoy. Next morning, the Frenchman decided his moment had come when the column reached a junction, out in the country. Convinced he could drive faster than the surprised Germans could shoot, Benoist floored the throttle, turned off the main road and drove as if his life was at stake. Which it was.