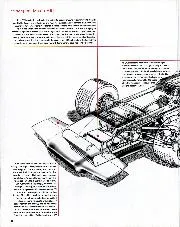

“I understand the car is now in a museum somewhere in Germany,” says Amon, adding after a long pause a heartfelt, “Long may it stay there.”

The Amon AF101 was a truly unsuccessful race car, but that doesn’t necessarily make it the worst. Curiously, that questionable honour could equally go to a machine in which Amon enjoyed some of his most significant F1 results, including a win in the Daily Express Trophy at Silverstone, and two Grands Prix second places. The March 701 is the only car in our conversation that raises the pitch of his voice a tad, so that those tales of his “purple wobblies” in the pitlane over a recalcitrant car suddenly ring truer.

“That was a dead basic, bloody ordinary car,” he says… and he still sounds exasperated by it. “I drove it very briefly at Silverstone the day March released it, and then we went down to South Africa for six weeks of development. By day two we went as fast as we were ever going to. The thing just had no development potential.

“It didn’t have very good traction, it slid all over the road, and whatever you put on in terms of springs and roll bars, it just kept on doing that. On a smooth, fast circuit it wasn’t too bad, but somewhere like Brands Hatch it was an absolute disaster. I could never even vaguely make it work there.”

Amon on the AF101: “I prided myself on my ability to develop a car, but this one just kept falling apart”

Grand Prix Photo

Amon’s reasons for joining March, a company that had only been formed a few months before the 1970 season began, can be summed up in three letters: DFV. After three years of acute exposure to the facilities of Ferrari’s V12, he was convinced he needed a Ford Cosworth V8 to win races. Testing of Ferrari’s new flat-12 engine, in late 1969, had convinced him. “First time out I knew it was way, way quicker in a straight line, but it broke a crankshaft after four laps. The next crankshaft lasted five laps. That was the point when I said enough is enough. I really, really wanted a DFV. Huge mistake.”