1983 Brazilian Grand Prix race report

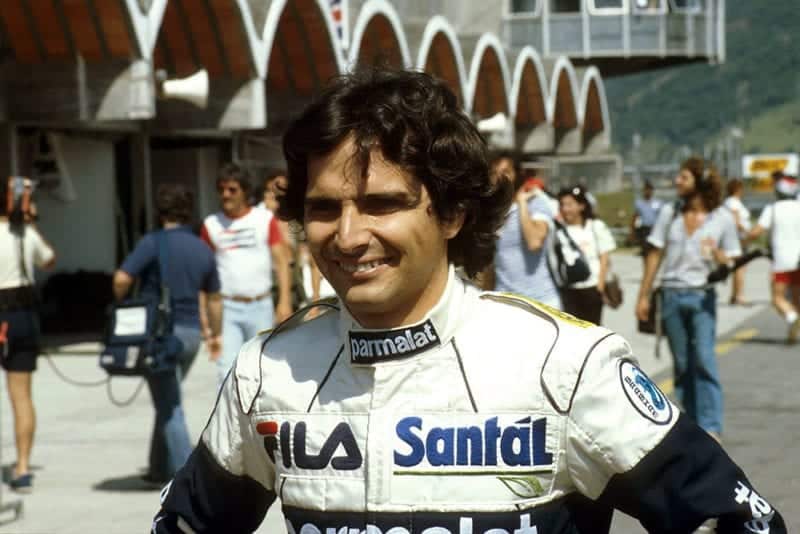

Nelson Piquet in his Brabham BT52 BMW

Motorsport Images

Rio de Janeiro, March 13th

By the time the massed ranks of the Formula One Constructors took to the circuit in Brazil for official pre-Grand Prix qualifying, most of the cars must have almost been in a position to run round the 3.126-mile Aurodromo Riocentrowithout their drivers aboard, such was the amount of pre-race testing that had taken place there since Christmas. There was obviously a great deal of speculation as to the performance of the “new breed” of Grand Prix cars which have come in, being since the FISA re-wrote the technical rule book abruptly at the end of last season, the ground effect concept now having substantially been banned by the requirement of a completely flat lower surface of the cars between the front and rear wheels. Despite a degree of initial grumbling from the Constructors, who said, of course, they could never get their cars ready in time for the planned start to the season at Kyalami at the end of February, FISA and the South African organisers obliged by postponing the race until the end of the season, thereby providing everybody with another two weeks’ grace before the first race. Interestingly, a large proportion of the teams had cars ready by the middle of January and were able to take part in the two Rio test sessions without much trouble, and, taken by and large, everybody had got their heads down and put in a tremendous effort. There was much new, and much revamped, to see in the sweltering Rio paddock, and details about the cars are presented separately from this report.

Testing the weekend prior to the race indicated that the British Toleman team had got things right with their totally revised TG183B powered by Brian Hart’s compact four-cylinder turbocharged engine. It’s a measure of how people can quickly change their standards that the Toleman lads, who twelve months ago would have been down on their knees praying with delight if they’d qualified in the top twenty, were slightly disappointed if they were anything but the fastest car on the circuit! Warwick had proved his worth as a driver by dominating the two pre-race test sessions, so it came as an enormous disappointment to him when he started the Brazilian Grand Prix from fifth place and not from pole position!

Qualifying

With lots of circuit experience under their belts, the competition was as scorching as the temperature from the moment the first practice sessions began on the Friday prior to the race. During the off-season there had been much speculation by various observers and teams that the day of the normally aspirated Cosworth DFV V8 engine was over, and that the 1½-litre turbocharged units would reign supreme throughout 1983. Well, although the stark results provided by the Brazilian Grand Prix may have tended to suggest this prediction is accurate, equally there were sufficient pointers to indicate that it is totally wrong!

Alain Prost in his Renault RE30C.

Motorsport Images

Unquestionably, the highlight of qualifying was the performance of World Champion Keke Rosberg and his Williams FW08C. By the end of the first session it was crystal clear that the Williams team had pulled off one of the great ruses of the past few years. During testing their Cosworth-engined cars had been average, even undistinguished, but it soon became clear that they had been taking things easy, deliberately running with high fuel loads and relatively hard tyres for much of the time. What’s more, when they did run quick laps, they moved their timing equipment away from the pits and timed from the hairpin, the easier to mislead their rivals as to their true capability.

Of course, one aspect of the rule changes which certainly did help the normally aspirated cars was the reduction of the Formula One minimum weight limit from 580 kg. to 540 kg. There in an enormous incentive to build down as close to this minimum weight limit as possible, many of the turbocharged cars clearly unable to get as near to it as they would like. But against this is a revised system to check the minimum weights, infringement of which now results in disqualification from the entire meeting involved. At the start of practice the drivers are weighed individually and their weights fed into a computer. Then, when the cars are weighed at computer-selected “random check”, which takes place during all qualifying sessions (and after the race, of course), their weight is automatically deducted from the total car / driver weight. Thus, if the net figure for any car falls below 540 kg. at one of these checks, the full force of the rule book comes down on the transgressor. What’s more, if anybody ignores the signal for their car to be checked, they can also be disqualified. This happened to Andrea de Cesaris in the Alfa Romeo V8 183T during final qualifying and, without any argument, he was disqualified from participating in the race. FISA certainly indicated their intention to apply the rules firmly and even-handedly over the Brazilian Grand Prix weekend, although whether it is relevant or valid to have any sort of minimum weight limit in Formula One is another matter altogether.

Rosberg’s splendid pole position lap of 1 min. 34.526 sec. was achieved in scorching air temperatures of around 110 degrees (F) during the Friday qualifying sessions, a perfect combination of top-line driver, agile chassis, soft Goodyear rubber and a powerful John Judd-modified Cosworth DFV engine. What’s more, the Williams team signalled its intention of taking a leaf out of the Brabham book and began preparing for a mid-race pit stop for the World Champion’s car. It was their intention that Rosberg would go as fast as possible on a half-full fuel tank, using soft rubber, in an effort to build up a substantial early lead. It worked to perfection, the only problem being that the Brabham team had identical plans for their striking new, and significantly faster, BT52-BMW driven by Nelson Piquet!

Rene Arnoux started 6th on his Ferrari debut

Motorsport Images

The next seven cars on the grid behind Rosberg were 1½-litre turbos, a crushing demonstration of the effectiveness of high-boost forced induction engines when it comes to “wringing out” a really fast lap during qualifying. In the Renault Elf pit there was quiet satisfaction that Alain Prost should have qualified second, particularly in view of the fact that he was still using an updated version of the 1982 car, dubbed RE30C. Prosts car was also fitted with experimental Brembo carbon fibre brakes, with single calipers, during practice and the Frenchman had a relatively straightforward time, returning a 1 min. 34.672 sec. best. By contrast, his new team-mate Eddie Cheever couldn’t find a clear lap in traffic on Friday and didn’t net his best qualifying time until the following day, managing a 1 min. 36.051 sec. best for eighth place, despite a minor collision with Eliseo Salazar’s RAM March which broke a wheel rim on the Renault as a result.

In the Ferrari camp there were glum faces to be seen, for neither Patrick Tambay nor Rene Arnoux were happy with the wheel-spinning 126C2s in their latest guise. Tambay began the weekend badly with a fuel vaporisation problem during Friday’s untimed session which jerked the car around so violently that the V6 engine sheared its distributor drive as a result. During the first qualifying session he managed a third fastest 1 min. 34.993 sec. lap, improving slightly the following day, but retaining the same place on the grid. On paper Ferrari’s prospects might have looked moderately promising before the start, but Tambay allowed himself no such optimism. “We’ve got a big problem with traction and trying to work out settings that will allow us to run non-stop in the race. We certainly don’t intend stopping for fuel because we don’t have the facilities here, and I don’t want to have to stop for tyres.” Tambay’s new team-mate, fellow Frenchman Rene Arnoux, never got going as well, spinning off on Friday and being unable to restart, while his 126C2 blew a turbo in Saturday’s qualifying session after he bad managed a 1 min. 35.547 sec. for sixth place on the grid.

The new Brabham BT52s were obviously attracting a great deal of attention in the pit lane and both Piquet and Riccardo Patrese proved that these very shiny new cars with their BMW turbocharged engines would be strong competitors from the outset. Both drivers complained of a worrying handling imbalance on the first day, but this was soon traced to the KKK turbocharger unit, mounted low down on the left hand side near the rear of the car, radiating heat on the left rear shock-absorber, thus overheating this component. Makeshift cooling ducts were made up for the second day’s practice and Piquet served notice of his race intentions by qualifying fourth behind Tambay. This was particularly encouraging since concern over the durability of the specially developed gearbox on these cars meant that they both ran pretty conservative amounts of turbo boost during qualifying and Patrese’s car actually broke its transmission on Friday as well as suffering a disconnected oil line, and consequent leak of lubricant, the following day. Patrese qualified seventh fastest, splitting Arnoux’s Ferrari from Cheever’s Renault.

Keke Rosberg in a Williams FW08C Ford

Motorsport Images

The Toleman team began the weekend in a slightly apprehensive frame of mind, for there were rumblings of discontent from some other teams about the eligibility of the two “interactive aerofoils” at the rear of the TG183Bs. Happily for them, the race scrutineers deemed the cars to be fully in conformity with the technical regulations and it didn’t go un-noticed by the Ligier team who quickly re-presented their cars with a similar, but not identical, aerofoil arrangement on their new JS21s.

Clearly hoping to sustain the domination he exerted during testing, Derek Warwick emerged from the first day slightly disappointed in fourth place on 1 min. 35.206 sec., frankly admitting that he’d “messed up” one corner on his second set of qualifying tyres. But he remained optimistic that he would be able to improve the following day. Unfortunately Toleman hopes were dashed in that respect with a major engine failure, on both Warwick’s and Giacomelli’s, both on their very first lap during the final qualifying session. Warwick’s car had previously stopped abruptly during the Saturday morning untimed session, and although electrical trouble was initially expected, it turned out that an inlet pipe to the compressor had failed on the Hart engine, it had lost boost pressure and the mixture had slipped onto full-lean. Clearly this must have damaged a piston, for the Hart engine failed in untypically spectacular style, blowing oil all over the place and destroying Warwick’s chances of improvement. Giacomelli’s problem turned out to be the result of an installation error: the turbocharger wastegate jammed shut with the result that Bruno’s eyes almost came out on stalks as the boost gauge needle wrapped itself round the dial! The little Italian revelled in what must have been the most powerful engine on the circuit — for two corners, before it, too, comprehensively broke.

Andrea de Cesaris in his Alfa Romeo 183T.

Motorsport Images

Thus Warwick had to content himself with fifth place, while Giacomelli was right down in 15th place. In ninth place came the second of the Cosworth-engined cars, Niki Lauda’s McLaren MP41C which, along with most runners on Michelin tyres, was handicapped by the fact that its qualifying rubber was hardly any better than the tyre they planned to race the car on. When Rosberg did his time, Lauda almost visibly rocked on his heels: “I can see how I might make up half the difference,” he said honestly, “but a full second and a half? No chance!” Designer John Barnard explained that they had changed the chassis settings from those employed during testing, but the experiment wasn’t working as well as he’d hoped, so they eventually re-traced their steps back towards the previous set-up. Watson, not happy with his MP41C’s handling, felt that he needed a couple of days more testing to get the best out of his machine and languished down in 16th place on the grid.

Michele Alboreto qualified his Tyrrell 011 exactly where one might have expected — the third Cosworth car on the grid, in 11th place. He suffered an engine problem on the first day of practice, but worked down to 1 min. 36.291 sec. on Saturday which was exactly 0.1 sec. faster than Jean-Pierre Jarier’s slimline Ligier JS21. When this new product of the French marque was first unveiled, many people wondered whether it would have sufficient cooling capacity with its tiny water radiators tucked in just ahead of the rear wheels, and after the first day in Rio’s searing heat, Jarier was similarly concerned. The water temperature gauge was reading well over 110 degrees (C) as opposed to the 95 degrees (C) it had recorded during the previous week’s testing. The car suffered an engine failure on Friday and Jarier’s spare had clutch problems, so it wasn’t until Saturday that he recorded his 1 min. 36.393 sec. lap. His team-mate, Brazilian Raul Boesel, was getting into the swing of things quite nicely and qualified 17th without any drama.

In the Lotus camp Elio de Angelis was finding the powerful Renault turbocharged V6 engine more than the combination of the 93T chassis and Pirelli tyres could cope with, the car sliding about under hard acceleration “as if it was running on ice”. Nigel Mansell concentrated his efforts on the Cosworth-engined 92, “active suspension” car, but both drivers were forced to take turns with the spare, Cosworth-engined, updated Lotus 91/92 on Friday afternoon when both their regular cars refused to run properly. On Saturday de Angelis got into the swing of things a little better with the Renault-engined car, qualifying up in 13th place, but Mansell had nasty moment when Marc Surer’s Arrows wandered across in front of him, the Lotus 92 sliding sideways up the circuit in a shower of dust, ruining what the Englishman felt was his best lap. He qualified a dejected 22nd.

The second half of the grid produced one or two surprises and several disappointments. Seriously embarrassing many of their more exalted rivals. the Theodore N183s (nee Ensigns) of Roberto Guerrero and former motorcycle Champion Johnny Cecotto qualified 14th and 19th respectively, Cecotto only having completed a total of 40 laps in an F1 car prior to the start of official practice. Their efforts shamed new Williams recruit Jacques Laffite who had no specific problem at the wheel of his FW08C apart from an inability to get the car adjusted to his liking: he only just managed to scrape onto the grid ahead of Cecotto by 0.4 sec., Marc Surer was suffering from some sort of bug and didn’t get the best out of his new Arrows A6 until the race morning warm-up, while Danny Sullivan was still learning about F1 in the second Tyrrell and Chico Serra wasn’t anything special in the second Arrows. Completing the grid was Corrado Fabi’s neat Osella FA1D, Manfred Winkelhock’s predictably troublesome and precarious-handing ATS-BMW D6 and Eliseo Salazar’s RAM March, the latter only scraping in after de Cesaris’ times had been disallowed. Thus the only non-qualifier was Piercarlo Ghinzani in the second Osella.

Race

Elio de Angelis was disqualified due to swapping into his spare Lotus after the parade lap

Motorsport Images

After the scaring heat and blazing sunshine of the two practice days, Sunday dawned slightly cooler and overcast, something which was keenly welcomed by the 26 young men who were preparing to strap themselves into confined F1 cockpits to race for just under 200 miles. Williams and Brabham were preparing to run Rosberg, Piquet and Patrese “light” from the start, stopping for fuel and tyres during the race, while all the other turbocharged cars were filled up to the brim with fuel and planned to go through without a stop. The huge Brazilian crowd which filled the vast grandstand on the back straight could obviously sense the possibility of a home win and cheered madly for Piquet as the field came slowly past on the warming-up lap prior to taking their places on the grid. Already Elio de Angelis’ Lotus was in dire trouble, belching smoke from one exhaust pipe to herald a turbocharger failure. The Italian staggered round two warming-up laps before being pushed from the grid, de Angelis then strapping himself into the spare 91/92 before starting from the pit lane after the grid had departed.

When the starting light turned green the field got away to a clean start, Prost edging alongside Rosberg into the first right-hander, but Keke gently eased ahead under braking and by the time the field streamed out onto the long back straight the white and green Williams was pulling confidently away from the yellow French machine. Going down to the hairpin Mauro Baldi’s Alfa Romeo gave Alboreto’s Tyrrell a hefty shove which resulted in the British car spinning wildly in the middle of the pack. Fortunately everybody avoided the wayward Tyrrell, but the impact had damaged its oil cooler and Alboreto eventually pulled in after seven laps to be posted as the 1983 season’s first race retirement.

At the end of the opening lap Rosberg had an amazing 2.5 sec. advantage over Prost, but the Brabham BT52s of Piquet and Patrese were third and fourth with the Ferraris of Tambay and Arnoux next in line. Then came Cheever’s Renault, Warwick’s Toleman, Baldi, Lauda, Watson (after splendid first lap), Jarier and the impressive Guerrero. By the end of the second lap Piquet had sliced past Prost into second place and it was becoming clear that the Brabham BT52 was easily the quickest car on the circuit. Within another lap the Brazilian had reduced Rosberg’s advantage to only 2 sec. and, as they went down the long back straight on lap seven. Piquet pulled confidently out from the Williams’ slipstream and moved decisively ahead as they braked for the long left-hand curve that followed. Patrese was moving closer as third place while Prost, heading the rest of the pack, was already dropping away significantly in fourth place.

Nigel Mansell in his Lotus 92.

Motorsport Images

With the status quo established at the head of the field, it was the battle for secondary positions which held the crowd’s attention. Watson was really flying in his McLaren, disposing of teammate Lauda on the second lap and moving through to take Baldi, Warwick and Cheever almost as if they weren’t there by the end of lap seven. By lap 11 he’d accounted for both the Ferraris, the heavy Maranello “fuel bowsers” in no position to fight back against the agile Cosworth-powered machine at this early stage in the race, and then he went after Prost. His whirlwind progress finally got him through into third place by lap 17 where he settled down, easing steadily away from both his pursuers without making an impression on Piquet or Rosberg who were now several seconds ahead of him. Patrese, meanwhile, had moved right up onto Rosberg’s tail by the end of lap 10, but just when it looked as if he would pounce on the World Champion, his Brabham suddenly slowed up and began to drop back again. By lap 18 he’d slipped back through the field to ninth, the BMW engine obviously not running properly, and then came into the pits to investigate the problem. An exhaust pipe had broken, so the engine’s turbocharger pressure had dropped dramatically: there was nothing more for him to do but complete another slow lap, just in case, and then pull in for good.

Thus, by lap 20 the order was firmly established as Piquet, Rosberg, Watson, Prost, Tambay and Baldi, with Lauda moving up to challenge Warwick’s Toleman for seventh. Baldi’s enthusiastic progress in the Alfa Romeo V8 was beginning to worry Warwick, for no matter how much he tried to find a way through, the Italian countered by taking distinctly unhelpful lines through the corners, and the British driver eventually decided to let Lauda through quickly to see if he could do anything about the problem. Sticking closely to the McLaren’s gearbox, Warwick tried to follow Lauda through when a gap presented itself to the Austrian, but while Baldi saw the MP41C, he didn’t see the Toleman coming through behind. In a trice, the Alfa Romeo was riding over the Toleman’s left front wheel, spinning to a halt in the middle of the track as Lauda and Warwick went on their way. His car’s rear suspension damaged, Baldi limped back to the pits and retirement, later to be retrospectively disqualified for the push-start he had received as he recovered from the spin!

Keke Rosberg has to vacate the cockpit after a fire started in the car

Motorsport Images

On lap 28 Rosberg pulled in for fuel and fresh tyres. Everything seemed to be going well, the wheels had been refitted and the mechanics were just pulling the fuel line away when a few drops of petrol dripped out of a leaking valve onto the hot engine bay. There was a brief burst of flame, quickly killed by an ever-present fire extinguisher, but not before Rosberg had unfastened his harness and prudently shot out of the car like a rocket. Almost immediately he was helped back into the Williams, his harness refastened and he accelerated back into the fray. But this unexpected drama had dropped him to ninth place and he went back on the track exactly a lap behind Nelson Piquet’s leading Brabham. Unfortunately, during the hurry to get the Williams back in the race, Rosberg had received a push-start for which he was to pay dearly later in the afternoon.

Of course, Piquet’s pitstop was yet to come, but on lap 40, the leading Brabham rolled into the pit lane to refuel and take on fresh tyres. Unlike last year’s BT50, the new BT52 isn’t fitted with an onboard air jacking system, so the Brabham mechanics had to use normal manual jacks when Piquet rolled to a halt. But everything went without a hitch, the car was only stationary for just over 16 sec., and the Brazilian tore back into the race with a 40 sec. advantage still intact.

Rosberg’s progress through the field was predictably quick, racing as he was on fresh tyres against rivals who’d run non-stop from the start. By lap 34 he was up to seventh, on lap 36 fifth and on lap 44 he was fourth ahead of Tambay’s Ferrari. Prost’s Renault succumbed on lap 46 and Rosberg finally raced past Lauda’s McLaren to take second place ten laps from the finish. Effectively, it was all over bar the proverbial shouting.

Confident and completely in command, Piquet wound down the cockpit turbocharger boost control in the closing stages and allowed his lap times to lengthen as he cruised home to a convincing first-time victory for Gordon Murray’s new Brabham BT52, making up for his disqualification from last year’s event when his Cosworth-engined Brabham BT49C fell foul of the minimum weight limit. Sadly, for Rosberg, who’d also been disqualified from second place for the same reason last year, there was no such consolation as his Williams was subsequently excluded for that push-start and the results beyond second place are now provisional subject to a Williams team appeal.

Lauda finished a smooth third on the road, ahead of Jacques Laffite who’d really got into the swing of things in the second half of the race and made up a great deal of ground towards the finish. Patrick Tambay survived to fifth, just beating off a last-ditch challenge from Marc Surer’s Arrows, while Alain Prost, worried by a severe vibration from his Renault, eased off towards the end and just pipped a disappointed Warwick for seventh. Tyre vibration, so serious that it caused Rene Arnoux’s Ferrari to throw off its rear wheel balance weights, slowed the Frenchman to the point that even Chico Serra’s Fittipaldi slipped ahead before the chequered flag. Completing the list of finishers were Sullivan’s Tyrrell, Mansell’s Lotus 92, the similar car of de Angelis (which was subsequently also disqualified as the driver changed his car type after the starting procedure had begun), Cecotto’s Theodore, Salazar’s March and Guerrero’s Theodore. The two Theodores had shown very well midfield during the early stages before both made pitstops to free sticking left rear brake calipers, subsequently rejoining and running without further delay to the chequered flag. — A.H.

Winner Nelson Piquet.

Motorsport Images

Results:

Brazilian Grand Prix – Formula One – 63 laps – AutodromoRiocentro – 5.031 kilometres per lap – 316.953 kilometres – Overcast and Hot

1st: Nelson Piquet (Brabham BT52/3) 1 hr. 48 min. 27.731 sec. ¬– 175.300 k.p.h.

2nd: Keijo Rosberg* (Williams FW08C/07) 1 hr. 48 min. 48.362 sec.

3rd: Niki Lauda (McLaren MP4/1C/7) 1 hr. 49 min. 19.614 sec.

4th: Jaqcues Laffite (Williams FW08C/08) 1 hr. 49 min 41.682 sec.

5th: Patrick Tambay (Ferrari 126C2/065) 1 hr. 49 min. 45.848 sec.

6th: Marc Surer (Arrows A6/2) 1 hr. 49 min. 45.938 sec.

7th: Alain Prost (Renault RE30C/12) 1 lap behind

Fastest lap: Nelson Piquet (Brabham BT52/3) on lap 4 in 1 min. 39.829 sec. – 181.426 k.p.h.

* Disqualified for infringement of rules