1979 South African Grand Prix race report

Gilles Villeneuve claimed his second career win at Kyalami

Motorsport Images

It rained!

Kyalami, March 3rd

Confusion rained at Kyalami long before the Grand Prix of South Africa was due to start. While everyone was heading for the southern hemisphere to continue test-programmes started in south America, or start new ones with new ideas and new cars, there were rumblings in the corridors of power. The Constructors’ Association met at the Ferrari factory in Maranello and announced that they would no longer deal with the CSI on Formula One matters and would only respect the FIA, but wanted complete control of Formula One. The FIA merely confirmed the existing system, in which all sporting control is delegated by them to the CSI (or Federation International du Sport Automobile as it has now become) and reiterated that FOCA was part of the Formula One Working Group within the CSI. All this meant that Ecclestone and his lot were no longer on speaking terms with Balestre and his lot, and under the stony silence of stale-mate the South African GP prepared to take place. Fortunately the business of operating and running Formula One cars is a complex one and a full-time activity so everyone was getting on with the job, leaving the talkers and petty politicians to their own devices.

After the severe ruffling that the Ligier team gave everyone in South America there was a lot of activity and most teams were out at Kyalami long before official practice began. Ferrari sent out two brand new cars, designated T4, which were a complete redesign around the proven flat 12-cylinder engine and the transverse gearbox/final drive unit, in an attempt to make better use of airflow. It did not take Scheckter and Villeneuve long to appreciate the new cars and the muletta T3 was soon discarded as being obsolete, yet only 12 months ago it was the latest thing from Maranello. Although everyone was twittering about “wing cars” and “ground effects” during the testing sessions, anyone who was paying attention to what was actually happening would have realised that brake-horse-power was the real name of the game, and in particular the ability not to lose what you had got. Kyalami lies 5,500 feet above sea-level and has a very long flat-out section. While everyone was fluttering about on aerodynamics Renault arrived with their 1978 cars, which are about as aerodynamic as a house-brick, and not much bigger than a Formula Two car, and blew everyone into obscurity by means of sheer b.h.p. The Ligier team did not arrive for any testing, preferring to experiment at Paul Ricard, in comparative peace and quiet.

Over the past ten years the South African GP has changed its character from one of a social gathering and a holiday to a high-pressure business activity for making the maximum amount of money in the minimum amount of time, just like any other Formula One Event. The race is always held on a Saturday and in the past practice was held on Wednesday and Thursday, with Friday kept clear for preparing the cars, the track and the organisation. Few people complained about the arrangement and for most if was very popular, but this year Ecclestone and his lot put a stop to it all by announcing that official practice would be on Thursday and Friday, with no break before the race.

Qualifying

Jean-Pierre Jabouille took Renault’s first pole

Motorsport Images

When the Kyalami circuit was opened for times practice on Thursday morning the skies were grey and over-cast and the temperature was distinctly cool, which was just what the turbo-charged Renault V6 engine wanted. While everyone else was worrying about their aerodynamics Jean-Pierre Jabouille went out and recorded 1 min. 11.80 sec., a whole second faster that most people had been doing during testing sessions, when hand-timing tends to be optimistic. Before a lot of people realised what had happened the sun came through the overcast and the air temperature rose dramatically and it was all over. The two Ferraris had almost broken the 1 min 12 sec. barrier, with Scheckter on 1 min. 12.04 sec. and Villeneuve on 1 min. 12.07 sec. The fastest three cars were all on Michelin tyres and horsepower was obviously still very important on a fast circuit like Kyalami. In a surprising fourth place was Lauda with the V12 Alfa Romeo-powered Brabham BT48, the new Italian engine beginning to look promising. After that it was the Ligier team once more leading all the Cosworth-powered cars, indicating that South American was not a flash-on-the-pan as far as Goodyear-shod “kit-cars” were concerned. With the rise in track temperature there was little hope of improvement and in the afternoon session the Renault team rested on their laurels and did not bother to practise. The new-boy of the team, Rene Arnoux, had done a respectable 1 min. 12.69 sec., which put him well among the favoured runners, so he didn’t practise in the afternoon either. For what it was worth Villeneuve was fastest in the afternoon, but a whole second slower than Jabouille’s morning time. The day ended on a slight air of disbelief, for after all the working and scheming and theorising about “ground effect” cars, the engine was still proving to be the real heart of a Formula One car. The Renault keeps demonstrating that its turbocharged 1½-litre V6 engine develops a lot of power, and its reliability factor is improving steadily. Nobody has ever doubted the ability of the Ferrari engineers to produce horsepower, and now it looked as though the new V12 Alfa Romeo engine was working well.

On Friday morning the regulation untimed session of practice took place and thought the weather was not hot by South African standards, it was still too hot for anyone to approach the pole position time of the Renault. The whole air of Friday was as if the previous day had not happened, for no matter what anyone did, or how hard they tried, there was little comparison between the results being obtained on the two days. Although happy with their performance the Renault team were not very confident, especially when Arnoux’s engine blew up during Friday morning. When the truth sunk in to some of the teams, that “ground effects” were no substitute for horsepower, we saw the remarkable sight of cars running without nose-fins and with minimal rear aerofoils, all aimed at getting more straight-line speed, but all to no avail. In fact, it became almost embarrassing to see who was copying who in their groping about in the aerodynamic darkness.

In the final hour of times practice Patrick Depailler was fastest, for what it was worth, but the grid positions did not alter much. Just before the end of practice Didier Pironi had a monumental accident when a rear wheel came off his Tyrrell 009 at some 150 m.p.h. and the car destroyed itself in the catch-fencing and against the barriers. The young Frenchman escaped with bruises and the team resurrected the prototype 009 for him to race. After the wreckage had been cleared, practice ran its final minutes but nothing startling happened. Fittipaldi had been making progress with his new F6 car until the engine blew up and he reverted to his 1978 car, only to record his best time, which set the thinking back a step!

Race

Jody Scheckter takes the lead in his Ferrari at the start

Motorsport Images

On race day the weather was still unsettled as everyone had a last-minute thrash round in the warm-up period on Saturday morning, while a very large crowd poured into the circuit. Overnight it had rained quite heavily and the dampness was still in the air, though the rack was clean and dry. The race was due to start at 2.15p.m. and run for 78 laps, a distance of 320 kilometres, and the 24 starters left the pits and made their way round to the starting grid, Andrettti, Reutemann and Jones putting in an extra lap while the stragglers were still arriving. The grid made interesting reading, in spite of having been virtually decided on Thursday morning. Jabouille was almost embarrassed at being on pole position, while alongside him Scheckter had the huge support of the crowd, in his home Grand Prix. The brand new T4 Ferrari looked functional, if not pretty, and in the second row was the other brand new Ferrari with Villeneuve looking as cool and calm as ever. Alongside him was the red Brabham BT48 of Lauda, its fin-less pointed nose looking very bare and accentuating the tubes and struts of the front suspension. From the back of the grid to the second row was progress indeed for a new car and new engine. Then came the pair of blue and white Ligier cars, leading the Cosworth brigade, and apart from Lauda’s Brabham, leading the Goodyear-shod runners. In row four was Pironi with the spare Tyrell 009, alongside Andretti with the latest Lotus 79, not by any means outclassed yet. In the next row was Jean-Pierre Jarier with the second Tyrrell 009 and with him young Arnoux after only one practice session with the second Renault. Then came Reutemann in the second Lotus, in a not very inspiring position, and with him young Nelson Piquet in his first serious drive with the new V12 Alfa Romeo-powered Brabham BT48. The remaining 12 runners were either uninspiring, unimaginative, or unfortunate. James Hunt spend a lot of practice explaining how he was going to retire at the end of this season, because he is frightened of hurting himself (he ought to retire now before he does hurt himself!), the McLaren team seem to have lost their way, the Arrows team have gone very quiet (which makes a change) and the Williams team is a shadow of last year.

With everyone ready to go a few rain spots fell on the Leekop end of the circuit and you could smell rain in the air, but on the grid all was pandemonium as the field set off on its pace lap. They arrived back on the grid in a good order, the starting signal came on and they were away. The turbocharged Renault engine has never been the easiest with which to make a standing-start, but Jabouille did a good job and it was only Scheckter’s Ferrari that led the Renault down to the first corner. Jabouille pulled over to the outside and sat it out with Scheckter through Crowthorne corner and down the sweep of Barbeque Bend. Side-by-side they took the 150 m.p.h. Jukskei Sweep and as they went into the sharp right-hander at Sunset Bend the yellow Renault took the lead. Rain was now falling steadily and spray was flying from the slick tyres. Lauda was in third place, but eased off in the rain and Laffite and Pironi went by the Brabham. On lap 2, Villeneuve headed Scheckter briefly, and on lap 3 the two Ferraris went by the Renault as the three cars headed into Clubhouse corner, behind the paddock. These three Michelin-shod cars had already left the rest of the field far behind, but then officialdom decided the drivers were incapable of driving on the wet surface and the race was stopped! The two Ferrari drivers and Jabouille had looked perfectly capable of coping with the wet conditions, as did Laffite, Pironi, Jarier, Andretti, Depailler and quite a few others, but someone decided it was dangerous and that was the end of the South African GP for nearly an hour.

It was decided that the race would be restarted in the order after two laps, in 2 x 2 grid formation, and would run for the remaining 76 laps. Although the rain ceased almost as soon as the race was stopped, the circuit was still damp and tyre choice was left to the individual driver. Driving a racing car fast is one thing; using your brain is another thing altogether, and when you have a young man who can combine both you have a good racing driver. One such is Gilles Villeneuve (and another following the same route is Nelson Piquet, but that is for the future). The decision was simple enough, did one restart on “wet” tyres and stop and change to “dry” tyres when the track dried, as it surely would, or did one restart on “dry” tyres, hoping not to lose too much ground during the “drying-out” stage. Of the 24 cars that were lined up for the restart only Scheckter, Depailler, Tambay, and Piquet decided to keep to “dry” tyres, the rest fitted “wet” tyres, whether Michelin or Goodyear. The next decision was how far to go on the “wet” tyres and, for the others, how fast to try and go on “slicks” on the slippery surface.

The line-up was in order they had been at the end of lap 2 in pairs, with Villeneuve and Scheckter in front, followed by Jabouille and Laffite, the Pironi and Lauda, Jarier and Andretti, Reutemann and Depailler, Tambay and de Angelis, Hunt and Jones, Arnoux and Watson, Stuck and Mass, Lammers and Regazzoni, Piquet and Rebaque, Fittipaldi and Patrese. Natural caution had put the Brazilian at the back and a slipping clutch had delayed the young Italian. At the second start Villeneuve took the lead on his “wet weather” Michelins, while Scheckter fought brilliantly to stay with him on his “slick” tyres. Jabouille had his Renault in third place, but poor Arnoux fluffed his start and got left behind. Before the end of the lap Lammers had got muddled up with Rebaque and while the Shadow was picked out of the catch-fencing the brown Lotus 79 carried on its way. Jabouille went by the slipping and sliding Scheckter, into second place, and Depailler wished he had restarted in “wet” tyres, as he lost adhesion and slid off the road on the third lap (the fifth in total). Arnoux was making up ground at a great rate, passing Rebaque and Fittipaldi, and then Piquet and Patrese.

Andretti brought his Lotus home in 4th

Motorsport Images

Tactics and cunning were now the order of the day, to conserve tyres or change them as the case may be. As expected the track soon dried out and the sun shone, and Villeneuve drove a race that was an object lesson to everyone. For 13 laps he increased his lead over Scheckter and then dived into the pits to change all four wheels and shot back into the race on new “dry” weather tyres, in second place but better equipped than his team mate. The two Ferraris were way out on their own and while Scheckter could be seen to be driving in his usual hard and brusque manner his young team-mate was driving in velvet gloves and shoes, not only holding station but doing so without putting any strain on the car or the tyres. Villeneuve was impressive by any standards, his Ferrari changed direction in a fluid manner, the power flowed smoothly to the rear wheels on acceleration and you could sense that he was driving with very sensitive finger-tips, whereas Scheckter was during with clenched fists and bravado the inevitable happened. Scheckter wore his Michelin tyres out and at two-thirds distance had to stop for a new set of wheels. Villeneuve sailed serenely by into the lead and coasted through the remainder of the race with effortless ease. On new tyres Scheckter charged as hard as he know how and it was courageous but pointless, the smooth young French Canadian had it all well under control. Although Scheckter got within sight of his team-mate, that was all he could do, Villeneuve made no mistakes, conserved his tyres and demonstrated the oldest requirement in the Racing Driver’s Manual, to drive smoothly and let the speed look after itself. There was a bare four seconds between the two Ferraris at the finish and it was as clean a sweep for Maranello as they could wish for. Two brand new cars and they finished first and second, with a new lap record by Villeneuve for good measure.

In Argentina we were impressed by Ligier winning first time out with a new design in Brazil we were impressed by Ligier finishing one-two. In South Africa Ferrari went one better. It looks like 1979 is going to be the season for being impressed.

One could have been excused for not noticing the other 22 cars in the race, but they were not too impressive. As already mentioned Lammers and Depailler were soon off the road, followed a little while later by de Angelis. Then Pironi retired when the throttle linkage on the cobbled-up prototype Tyrrell 009 came adrift. A deflating tyre caught out Laffite and he spun off the road and Alan Jones had a 150 m.p.h. spin when the left-rear suspension collapsed on his Williams. Arnoux had been making a good recovery from his poor start and was going well when his left rear tyre punctured on some of the bits scattered from the Williams and he had a lucky escape when the Renault spun off the track. Jabouille’s hopes of an honourable race disappeared when he stopped for “dry” tyres, and then ended when the Renault engine broke. Nelson Piquet “pussy-footed” along in the opening stages but then ran a smooth non-stop race, profiting from other drivers’ pit-stops to move quite high up the field. When Lauda eventually caught him after changing to “dry” tyres, the young Brazilian stayed with his team leader right to the end, though it must be recorded that they were lapped by the winner. Driving a very smooth and consistent race into third place was Jarier with the Tyrrell 009 and he was pursued throughout by Andretti in the green Lotus 79. Now either Jarier was driving brilliantly, or Andretti wasn’t trying too hard, and with only third place at stake it was probably the latter. After working away for an interminable number of laps Andretti at last looked as though he might do something about the blue Tyrrell, but then they lapped Regazzoni in the second Williams, and while Jarier nipped by, Andretti got bogged down and lost all his advantage. Hunt raced the new Wolf against the old Williams of Alan Jones, until his accident, so there was obviously something wrong there somewhere, and the McLaren team and the Arrows team did not even provide a good supporting cast.

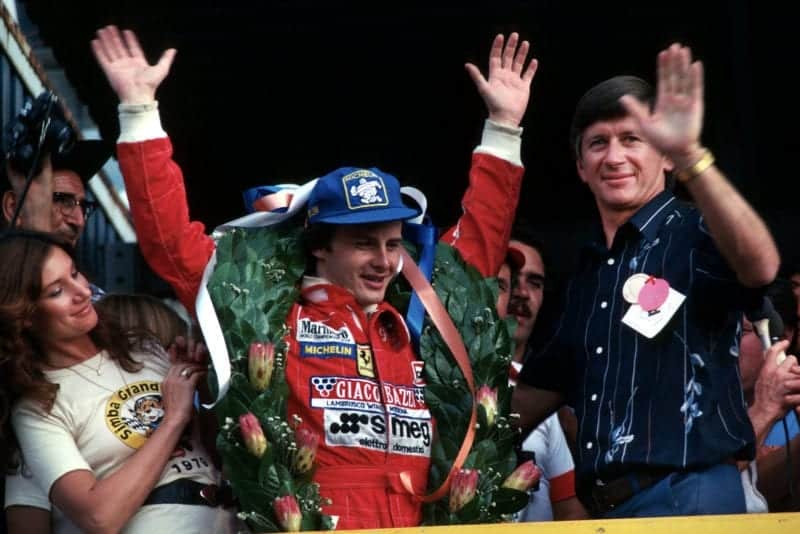

A delighted Villeneuve acknowledges the crowd

Motorsport Images

After it was all over there were the usual excuses and explanations of “why we didn’t win”, ranging from Reutemann having to pump the brakes on his Lotus before each corner, through the rear aerofoil coming loose on Lauda’s Brabham, to one tyre “growing” in diameter more than the other on Andretti’s Lotus and upsetting the balance. A pleasant change was Jarier, who was delighted with his third place and his Tyrrell 009 which had presented no problems. It recorded the highest speed through the timing beam on the descent after the pits, with a speed of 292.76 k.p.h. (approx. 182 m.p.h.) – D. S. J.