From Cardboard Model to Supercar Legend: The Jaguar XJ220 Story

Taking a road car racing was the foundation stone of Jaguar’s Le Mans successes during the 1950s. Four decades later, it decided to revive the principle with the XJ220

Jayson Fong

Despite being armed only with the rear-view mirror of a Fiat Punto, I was able to see the bigger picture. On a picturesque Staffordshire B-road, what followed appeared to be part-car, part-spaceship – something from a future century, though its roots lay squarely in the one before. Styled in the late 1980s and delivered to its first customer 25 summers ago, the Jaguar XJ220 is the very definition of timeless.

“The rules were simple: you couldn’t work on this in Jaguar time and you wouldn’t be paid”

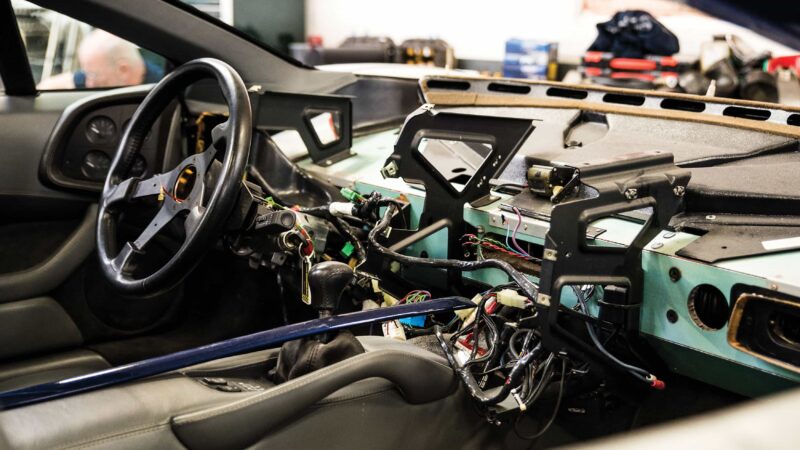

We were in rural Staffordshire because the village of Hill Chorlton has become the epicentre of global XJ220 maintenance. Well known in historic motor sport circles, Don Law Racing first worked on XJ220s in 1996 and prepared a couple for competition the following year. When Jaguar’s then-owner Ford decided to close the company’s specialised JaguarSport division in 1998, Law accepted an offer to take on the XJ220 business and is now equipped to look after the 281 such cars Jaguar built. They come to him from all around the planet, some with mileages commensurate with their age and others having barely been used since delivery – if, indeed, they have been driven at all. At the time of our visit, there were more than 20 on site, not to mention half a dozen XJR-15s, a Lancia Delta S4, a BMW M1 and, obviously, an Austin A35 pick-up.

XJ220s in various stages of repair and build.

Jayson Fong

Also present were the XJ220’s instigator Jim Randle and his stylist Keith Helfet, there to discuss the car’s genesis as part of the build-up to a 25th anniversary celebration at this year’s Silverstone Classic, when the largest ever gathering of XJ220s – possibly as many as 40 examples – will take part in commemorative parades.

In a world where manufacturing decisions are driven by teams armed with suits and spreadsheets, the story of the XJ220’s evolution is a refreshing contrast. “I had nothing to do during one Christmas break,” Randle says, “and was feeling bored. I’d long liked the idea of the way Jaguar tackled motor sport in the 1950s, with its C- and D-types that could be driven on the road to Le Mans and then raced. During the 1980s we’d won in the European Touring Car Championship, with the XJ-S, and had been successful in Group C, so I quite fancied doing something that harked back to a previous era. I made a quarter-scale cardboard model and gave it to my stylists so that they could play with it. They came back with two ideas, one that looked like a Porsche Group C car of the day and Keith Helfet’s design, which we chose.”

The initial V12 plan was dropped for a V6

Jayson Fong

Initially, though, the project was to be known only to those directly involved. “John Egan [Jaguar CEO and chairman] was aware I was doing something,” Randle says, “but he didn’t see the car until about two weeks before it was unveiled at the 1988 British Motor Show in Birmingham. If I’d put it to the board to do it properly, I’d have had to ask for a couple of million quid. I wasn’t going to get that, so did it in such a way that it wasn’t going to cost the company a penny.

“It was underlined that this was unofficial, real skunkworks stuff”

“I always thought I could pull it off and asked for volunteers, which I got. The rules were simple: you couldn’t work on this in Jaguar time and you wouldn’t be paid, although I promised that they would be recognised longer term. They were all given a specific area of the car to work on and entrusted to make their own decisions. They could come to me only if they found a decision too difficult to make. Of course, I know some of them did work on the project in Jaguar time, but I never caught them…”

Helfet remembers this well-intentioned subterfuge very fondly. “Conversations about doing a car like this had been bouncing around for a while, then during the Christmas holidays – I think on Boxing Day – Jim called me at home and said, ‘I’m working on a chassis and want you to put a pretty body on it.’ You don’t turn an opportunity like that down, but Jim underlined that this was unofficial, real skunkworks stuff. He asked me to do some sketches, but I said, ‘Jim, you know I don’t sketch – I make models.’ So I did a few doodles. I’m the only car designer I know who can’t produce beautiful drawings, but I’m quite a good sculptor. What happens in my head is three-dimensional, so I just got on with creating something for a chassis that was supposed to incorporate a V12 and four-wheel drive.

“By the time we started in earnest, Jim had assembled a dozen volunteers and we had the nickname ‘The Saturday Club’ because we’d meet up at the weekend to discuss progress. The rest of the time we all just did our own thing. The project was known only to departments that had some input: the guys in engineering knew a lot about it, but sales and marketing definitely weren’t in the loop. One of the reasons was that they would have taken a ‘grey suit’ approach to the whole thing and Jim definitely didn’t want that. Once we started building the thing it was all done off-site.

“As well as the in-house volunteers we had lots of serious companies providing their services for free. When Connolly sent some hide, our trimmer Callow & Maddock told us it was the finest they’d ever seen – they couldn’t buy leather like that and we were getting it all for free. That rather typified the project. It was such a labour of love, a passion-driven thing, that only the best was good enough. That was the adage for the first concept car. It was a real team effort. I love skunkworks-style projects…”

Randle: “It was a good time – but the guys worked ridiculous hours. During the week they’d focus on the XJ220 from 6.00-8.30 in the morning, then go and do a full day’s work at Jaguar before going back to do more on the XJ220 until late in the evening. That went on for months and included a lot of weekend work. Once the car had progressed to a certain point, it was very difficult to stop it.”

So well received was the XJ220 at its Birmingham launch that some potential customers famously handed the company blank cheques by way of deposit, so keen were they to acquire the new V12-powered four-wheel-drive supercar. “As soon as we announced it,” Randle says, “people were coming forward with £40,000 deposits and we had enough money to go ahead with the project, so essentially it didn’t cost Jaguar anything. It illustrated that you didn’t need thousands of people – or millions of pounds – to do a job.”

Between then and the XJ220’s formal introduction, however, two things happened. One, the market for performance cars as appreciating assets collapsed; two, Jaguar opted to abandon its complex four-wheel-drive V12 concept in favour of a rear-drive V6 turbo. It would still be the fastest production car of its day – clocked at 212.3mph during factory testing – but the altered spec and wobbly financial climate triggered a spate of cancelled orders. When Law Sr went to look at the XJ220 inventory, more than 100 cars were stored beneath covers at Jaguar’s old Browns Lane factory. “They looked quite ghostly,” he says.

With hindsight, though, the keepers of the XJ220 flame believe the company took the correct decision. “The V12 would have been old-fashioned, too big and had too much weight high up – and with four-wheel drive it just wouldn’t have worked as well,” says Don Law. “They had to use what was available – plus they had the benefit of V6 turbo experience from the XJR-10 and XJR-11 racing cars.”

His son Justin, who has driven XJ220s competitively and has probably covered more miles in an XJ220 than anybody, adds: “The V6 is half the weight of a V12 and half the physical size, so the car doesn’t have to be so long, and the turbo is so tuneable. A full-race V12 would give you 700bhp and that would be about it. We think the V6 can be tuned reliably to about 1000bhp – that’s the magic target.” He regularly drives a car with 800bhp-plus; the one in which he takes me for a spin has “about 630” and slabs of low-end torque that make it as responsive as you’d hope it to be. It doesn’t look like a 25-year-old car, nor does it feel like one.

“After the launch, a gentleman called and asked me to design an MRI body scanner”

For Helfet, the visit to Don Law’s workshop heralded the first time he’d seen any XJ220, let alone 20-odd, for about five years. “I think it still gives me the same warm feeling. It has such presence,” he says. “Early during testing, I saw a bunch of schoolboys by the side of the road and was aware that one of them had clocked me. As I went past I noticed them reacting and suddenly they all started clapping – a spontaneous reaction from a bunch of young boys, which was heart-warming.”

Other early tests were more covert, conducted using bits of XJ220 running gear installed in the back of a Ford Transit van. That eventually broke its (standard!) front suspension after being timed at 172mph around the Millbrook Proving Ground, but the Laws have restored it and fitted a fuller set of XJ220 underpinnings to prevent it shaking itself apart.

“Jaguar’s founding father Sir William Lyons died in 1985 and wasn’t around when I was doing the XJ220,” Helfet says. “He had a fantastic understanding of form – like me I think he was a frustrated sculptor – and I felt his spirit at my shoulder the whole time I was working, wondering whether he’d approve. The earlier Jaguars of Sir William and Malcolm Sayers were all about design language – they were beautiful because of the surface sculptures, the movement within the body form, curves that were always accelerating or decelerating. That’s why people said the E-type looked as though it was doing 100mph while standing still. It was dynamic because of its surfaces and shapes. I wanted to continue that theme with the XJ220.

“The bodies were done by Park Street Metal, where the guys were taking flat sheets of aluminium on rolling machines and tapping them into shape – I felt so guilty for making their job so tough. I later apologised to them and one replied, ‘You don’t have to apologise, it was hard but this has been the highlight of my career!’ I thought about that. It was difficult, but we were all so proud.”

As a postscript, the XJ220 influenced Helfet’s career in a way he could never have imagined. “The XJ220 was important on a personal level,” he says, “because it put me on the car design map. After the launch, a man called and asked me to design an MRI body scanner. I didn’t even know what an MRI was then, but they wanted me to apply the same sculptural principles and I ended up doing several. Happily, I didn’t have to worry about the clever bits inside…”

Taken from Motor Sport, August 2017