Inside the Mike Hawthorn Museum: A Rare Glimpse into Racing History

What started out as a family restoration project soon snowballed into a historic and storied collection detailing the life and achievements of Mike Hawthorn

Lyndon McNeil

This is the only thing that survived the fire,” says Nigel Webb handing me a small, but weighty piece of a Jaguar emblem, cast in solid bronze. “It’s the top of what used to be Mike’s ink blotter, used for signing his name on official papers. The fire destroyed everything else, which is tragic. Imagine how packed this place could be had the vast majority of the Hawthorn legacy not been ordered burned…”

That’s a sad thought, but in a way only serves to make Webb’s work all the more impressive. For, at his home – scarcely 50 miles from Hawthorn’s native Farnham – he has amassed what is likely to be the most expansive collection of Mike Hawthorn memorabilia in the world. A self-confessed collectomaniac, Webb has made it his mission to obtain and preserve as many genuine Hawthorn artefacts as possible, and his resulting self-curated museum is a treasure trove of personal items, literature and, of course, cars.

The base of Hawthorn’s 1958 world championship trophy is all that remains of it.

Lyndon McNeil

It’s highly private and usually accessible only by invitation or special event, but Motor Sport has been granted a rare tour ahead of a world-first public exhibition of the memorabilia to mark the anniversary of Hawthorn’s death. [The exhibit was later held at Race Retro, powered by Motor Sport, Europe’s leading historic motor show on February 22-24 at Stoneleigh Park in Coventry]. For the first time members of the public were able to get up close to many of the artefacts that Webb has curated over the years and which tell the story of one of this country’s most brilliant, but also perhaps most misunderstood world champions.

Back at Webb’s collection, the walls of his makeshift museum within a dedicated outbuilding are lined with images – from period photographs to huge original portrait paintings and caricatures – and chunky box frames containing items such as steering wheels from ex-Hawthorn cars – all four-spoke, of course. Everything is preserved in its own snapshot in time, but one particular frame stands out.

Hawthorn’s BRDC badge

Lyndon McNeil

“I obtained that from Duncan Hamilton’s family – it’s Mike’s famous flat cap and the keys from the Mk1 Jaguar he was killed in.”

Really..? There’s a story behind this, surely? “Mike and Duncan were great friends, and they always had an agreement that if one of them died, the other would perform the duty of identifying the body – to save their mothers having to go through that,” Webb adds. “After Duncan went to identify Mike’s body following his fatal crash in the Mk1, Mike’s mother – Winifred Hawthorn – handed him the cap and the keys, which had been given to her by the policeman who attended the accident scene. The Hamiltons kept them until I got them.”

A short, but poignant story. And there’s one to go with pretty much every one of the hundreds of pieces to be found in this remarkable collection.

A letter from the late John Surtees hangs on the adjacent wall. Addressed to Webb, it explains that Hawthorn was the very reason he ever found himself in a racing car. A throwaway comment from Hawthorn to then 350- and 500cc world motorcycle champion Surtees during a 1958 prizegiving suggested: “John, why don’t you try a car, they stand up easier…” To which the attending Tony Vandervell of Vanwall and Aston Martin’s Reg Parnell both responded by offering Surtees tests which led to “contracts for both” and “sowed the seeds for me to actually have my first race in a car in 1960.”

Hawthorn’s personal effects donated by a former girlfriend

Lyndon McNeil

A remarkable example of the previously unspoken influence Hawthorn had over an industry he dedicated his life to.

But how did this all start? Webb made his business in the aviation industry in the 1970s, and returned to England determined to pursue his passion for Jaguars, spurred on by his fellow Jag enthusiast father, Gerald.

“Many items were effectively stolen before they could be burned”

“I began to collect Jaguars after my dad had bought me an XK150 from a scrapyard and an SS 100, and then I bought an E-type,” explains Webb. “I had every intention of just making a Jaguar collection, but my dad was very much a Hawthorn fan. When I wanted something different from Jaguar, he suggested we instead built a replica of 881 VDU – Hawthorn’s 3.4 MK1. I went to Jaguar Cars and did a thesis on the car, which was destroyed after his accident, and came back with everything we needed to make a carbon copy of it – from the correct ignition barrel numbers down to the hand-operated radiator blind, which was often confused for a hand throttle on Mike’s car.

“During the restoration I met a lot of very passionate people who had known and worked with Mike and got caught up in his story and the goodwill and love people had for the man. I was 11 when he died, so it meant very little to me at the time and he was just a name. But as I’ve grown up, he’s become a larger figure in my life, so I started collecting the odd thing, and quickly it grew and became a Hawthorn museum, instead of a Jaguar one.”

Hawthorn’s bow tie donated

Lyndon McNeil

Standing proudly at the centre of the room are a series of Hawthorn-related Jaguars. There’s the replica Mk1, stunning after a decade-long restoration. “I’ve even got the original BRDC and Jaguar Enthusiasts’ Club badges from the front of the Mk1 Mike was killed in on it,” says Webb. “They surfaced relatively recently when the son of the policeman who recovered them from the wreck offered to sell me them.”

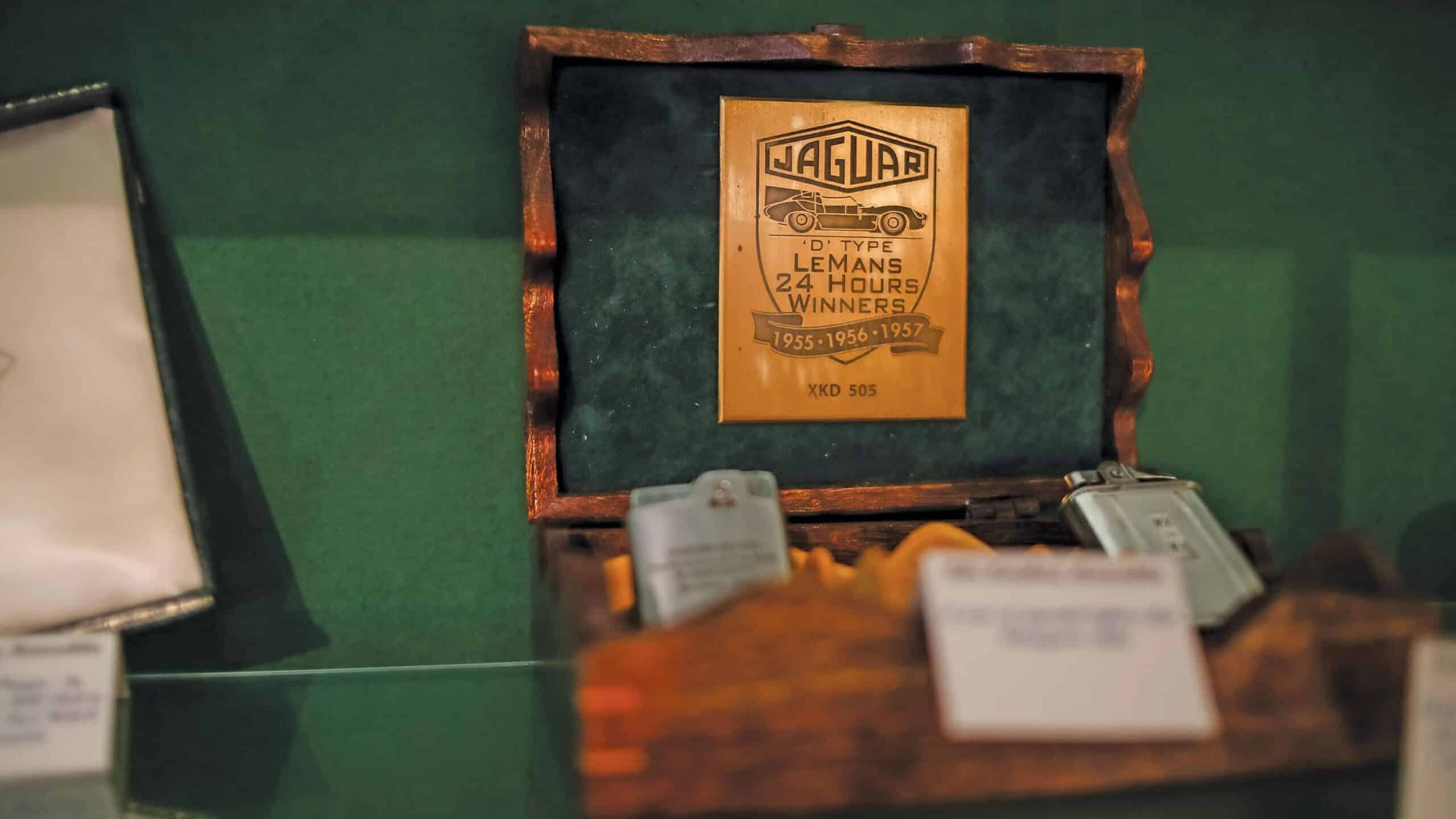

The collection is headlined by Webb’s own version of Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb’s 1955 Le Mans-winning D-type. While it’s not the exact car that won that fateful race, Webb tells me that it is built up from the chassis of XKD 505, although some may dispute this. However, it remains the closest thing we have today of Hawthorn’s car.

Webb also shows me Hawthorn’s winning drivers’ trophy from the ’55 race, which is stunningly plain, and rather smaller than you’d have expected. But weren’t all of Hawthorn’s trophies burned?

“You have to remember that Mike’s mother had already endured the loss of her husband and Mike’s father – Leslie – in 1954, which took a big toll,” says Webb. “When she lost Mike, he was much bigger than his father was in the eyes of the press and she couldn’t cope, so she ordered the housemaid to burn Mike’s possessions so the press couldn’t see anything. The housemaid was married to one of the mechanics from the Tourist Trophy Garage, which Mike ran. A lot of pieces were effectively stolen, such as the steering wheels Mike had collected, before the housemaid could do her duty.”

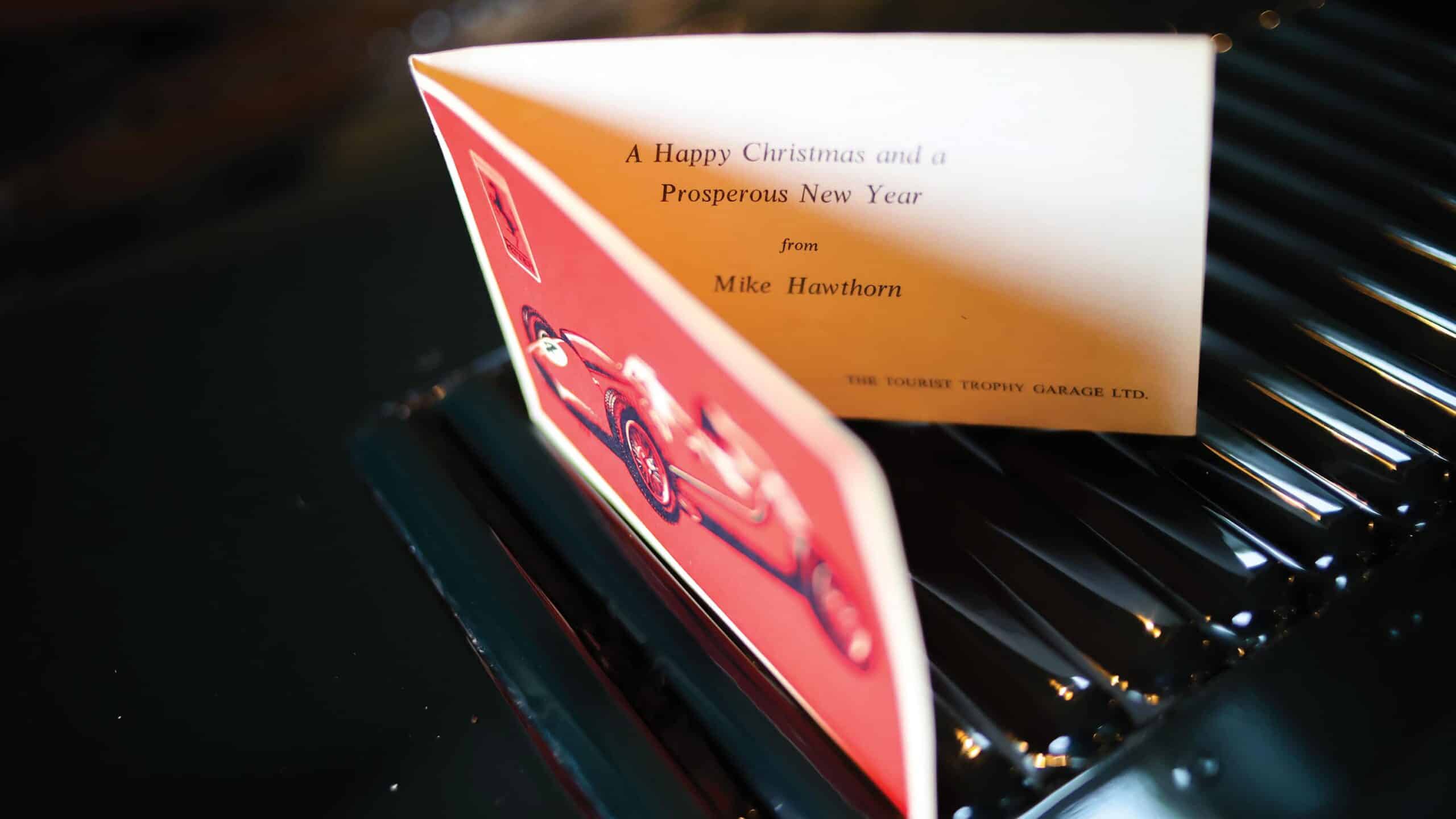

Scuderia Ferrari Christmas card

Lyndon McNeil

The recovered items have gradually come to light, with Webb scouring auctions or being contacted by privateers or even ex-girlfriends of Hawthorn willing to donate their trinkets.

Hawthorn’s fiancée at the time of his death, fashion model Jean Howarth (who later married Innes Ireland) has been a big contributor, donating many of Hawthorn’s personal effects from Jaguar. Another gave Webb one of Hawthorn’s famous spotted bow ties and a gift of a miniature Khanjar (a small, curved Arab knife) Hawthorn had once bought her.

“Mike would save the champagne to share it with the mechanics”

One standout auction find is the base of Hawthorn’s 1958 Formula 1 World Championship trophy, which Webb won at a Sotheby’s sale. Forged from solid marble with four brass racing cars mounted on top of it and the holes where the four supporting pillars would have been still visible, the trophy was ordered broken up after his death. Only the base remains.

“I was lucky enough to meet many of the mechanics from the TT Garage, and they would tell me amazing stories about Mike,” Webb adds. “For example, a few days after he won the world championship he returned from Morocco with a crate of champagne which he took into the workshops and he spent the day sitting on a wooden crate drinking with them to celebrate. That’s really special, and it wasn’t for show. I often asked them if the niceties had been put on as a show, but they said he rarely opened the bottles of champagne he got at races – he preferred beer – but he’d bring them back to the workshops for the mechanics. His personality is one of his most endearing things about him.”

Scuderia Ferrari figurines and Signatures

Lyndon McNeil

The curation of the Hawthorn museum has taken many years – since 1998 in earnest according to Webb – and in doing so Webb has also gained the support of some of the sport’s biggest names.

“Sir Stirling Moss has been a wonderful help,” he says. “I’ve amassed around 1000 photographs of Mike, and many times I’ve sent them off to Sir Stirling to ask, ‘Who’s that bloke behind you and Mike?’ and he was happy to write the names of the people on the back along with details such as where the picture was taken and when and then send them back to me.

“He and Mike were rivals during the 1950s, and Lofty England (former Jaguar team manager) once told me a great story about 1954, when Moss was already driving for the team and he introduced Mike to them for 1955. Moss said ‘Well, I will be number one driver, won’t I?’ and when Lofty said it would be 50/50 between them, Stirling effectively quit and went off to join Mercedes. It was a shame they were never team-mates as they’d have been formidable, but there was always a good camaraderie between them off the track.”

So, what of the future for this unique Hawthorn museum? “I have a problem in that respect,” says Webb. “I never at any point actually thought ‘I’m going to start a museum about Mike Hawthorn’; instead it just grew organically into one. And only now it’s dawned on me that I’m actually responsible for something quite special, something that shouldn’t be lost. But what am I going to do with it in the future? Finding somebody else to take it on would be incredibly difficult, and Jaguar won’t want it as it’s such a small section of its history and there will always be a black mark against Le Mans in 1955. Mike always blamed himself for that accident, anybody I ever met who knew him told me so. He was haunted by it. There are plenty of theories and it’s been analysed countless times. I don’t think he was to blame.

Webb’s collection of ex-Hawthorn steering wheels, including a bent Lotus 11 one from an accident at Goodwood.

Lyndon McNeil

“Mike was never in the sport for money. But he was always told he’d never live beyond 1965 due to his fading health [he suffered from worsening kidney disease, and had already lost one]. There was no dialysis technology then, nor any ‘spare parts’ transplants. If it were today, he’d probably still be alive. His career may have been short, but what a wonderful legacy.”

Singly, the wealth and range of ornaments to do with Hawthorn would mean very little. Just a memento or curio associated with the arguably fading legend of Britain’s first world champion. But collectively, Webb’s collection does so much more than that. It bombards you with aspects of Hawthorn’s life and time that together create a far fuller picture of the man behind the wheel. It’s thanks to the work of Webb that we still have somewhere that can both inform and celebrate one of the country’s sporting pioneers.

Taken from Motor Sport, August 2019