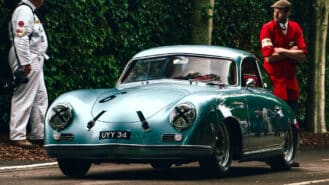

Denis Jenkinson's Porsche 356 roars again at Goodwood

Six decades after Motor Sport's famous continental correspondent Denis Jenkinson ran his Porsche 356 across Europe, it's now racing again following a long and careful restoration

Ended 30 years ago on safety grounds, the Group B era is still regarded by many as the World Rally Championship’s apotheosis. Brutality, meet romance.

Taken from Rallying Legends – available from the Motor Sport shop

Bare numbers rarely tell a full story, but in this instance they offer a reasonable clue. When Lancia produced its first Group B rally car, the Beta Montecarlo-based 037 in 1982, its supercharged, four-cylinder engine developed about 250bhp. By the time it conjured its last, the Delta S4 in 1986, an evolution of that same unit had gained a turbo and was rated at the best part of 500bhp, or perhaps slightly more. But such was the spirit of the age. Rallying’s power explosion coincided with a similar – but perhaps even more extreme – philosophy in Formula 1, where BMW conjured an estimated 1400bhp from a 1.5-litre turbocharged four-pot, essentially a grenade with a life expectancy of one qualifying lap. Motor sport and conspicuous consumption have always gone hand in hand, but perhaps never more so than during the mid-1980s.

Such was the backdrop to Group B’s genesis. To encourage manufacturer participation the formula was introduced with relatively few technical restrictions – and the rules required entrants to build just 200 road-legal examples of a car to qualify it for competitive homologation. Lancia and Citroën ran GpB cars in the 1982 World Rally Championship, but from 1983-86 all factory teams embraced the new category. It was a period that conjured some of most iconic and/or distinctive cars this sphere of the sport has known: the Lancia 037 and Delta S4, assorted Audi Quattro iterations, Peugeot 205 T16, Opel Manta 400, Renault 5 Maxi Turbo, Nissan 240RS, Toyota Celica TCT, MG Metro 6R4 and Ford RS200 all spring to mind, though people might draw the line at the bulbous Citroën BX4TC.

At the same time, the pool of driving talent was equal parts depth and breadth. The four period champions were Hannu Mikkola, Stig Blomqvist, Timo Salonen and Juha Kankkunen, while key rivals included such as Walter Röhrl, Markku Alén, Ari Vatanen, Michèle Mouton, Henri Toivonen, Jean Ragnotti, Miki Biasion and Björn Waldegård. Compare that with the number of potential winners in WRC events today and the era’s appeal seems obvious.

“It was more exciting then,” Kankkunen says. “You had the best drivers in the world and the standard was very high – anybody from the top 20 could win. It was not like today when only one or two drivers have a chance. It was more exciting. It’s better for spectators when cars are noisy and powerful. Nowadays the cars are not so spectacular to watch. The top drivers are really fast, but it has become more sanitised.”

And yet, and yet…

Given rallying’s natural terrain, GpB’s potential risks seem all too obvious with hindsight yet were given little thought as the category evolved. Roland Gumpert, father of Audi’s Quattro, says: “For me it was the greatest time in rallying and far more challenging than today. Perhaps it’s unfair to make that comparison, because I’m no longer involved, but I do believe it was more interesting for spectators. We didn’t really understand that we were making any kind of history – it just felt like normal work. We didn’t think we were crazy, that the cars were crazy or that the spectators were crazy, even though at the time it wasn’t unknown for them to congregate at the edge of the road.”

There is a video clip of Röhrl’s Audi in action on the 1985 Portuguese Rally and it encapsulates the zeitgeist far better than mere words could ever manage, a cocktail of wonderful car control and absolute faith that spectators would scamper out of the way as required.

“We started with 320bhp and tried to use Audi’s advertising mantra – Vorsprung durch Technik – to develop the suspension, gearbox and, obviously, the engine,” Gumpert says. “Versions of that same five-cylinder block are still being used today, so it must have been pretty good. It’s difficult to be certain how much power we eventually obtained. When we went to Pikes Peak in the mid-1980s people were saying we had about 1000bhp, but I think 700 is a more realistic figure.

“Nowadays teams have electronics to smoothen the power delivery, but with our turbo we had huge lag. The biggest problem was that we had lots of power, but initially it was all between 5000 and 7500rpm. We were eventually able to produce some torque lower down the range, but it wasn’t like today when there is no hole in the curve at all.”

The line between dramatic brute force and disaster would, though, eventually be crossed.

* * *

On May 2 1985, works Lancia driver Attilio Bettega perished after crashing his 037 into trees bordering the route of the Tour de Corse, although co-driver Maurizio Perissinot walked away without a scratch.

During the opening stage of the following year’s Portuguese Rally, national champion Joaquim Santos lost control of his Ford RS200 and spun into the crowd, killing three spectators and injuring more than 30. Ford pulled out of the event as soon as it realised the calamity’s scale and factory drivers from other teams also subsequently withdrew, issuing a statement that explained their decision was: “1) A mark of respect for the families of the dead and those injured. 2) There is a very special situation here in Portugal and we feel it is impossible to guarantee the safety of spectators. 3) The accident was caused by the driver having to try to avoid spectators that were in the road. It was not due to the type of car or its speed. 4) We hope our sport will ultimately benefit from this decision.”

Writing in the April 1986 edition of Motor Sport, Gerry Phillips reported: “So crowded was that stage, and so unconcerned were the organisers that the road itself was crammed with a solid mass of excited, uncontrolled, almost hysterical humanity until seconds before a car arrived, that the responsibility must be theirs alone.

“Spectators crowd the roads completely and part only to form a narrow avenue for oncoming cars when they are just yards away, and even then they stay close enough to reach out to touch them as they pass, drawing applause from their fellows if they succeed; amateur photographers squat in the middle of the road, determined to get the business end of a rally car as large as possible in their frames before jumping clear; where a wall borders the outside of a bend, it will be completely hidden from a driver’s view by a solid row of people sitting or leaning on it, and it is a point of honour not to get scared and move away: escape roads are blocked, and crews find it impossible to use pace notes because landmarks, junctions and verges are all invisible.”

And then on May 2 – the first anniversary of Bettega’s death – Lancia star Toivonen left the road while leading the Tour de Corse. His Delta S4 plunged into a ravine and burst into flames, killing the Finn and co-driver Sergio Cresto.

For the FIA that was the final straw. Group B would continue for the campaign’s final eight WRC events – the last of which, the Olympus Rally in America, fell to the Delta S4 of Markku Alén and Ilkka Kivimäki – and would thereafter be canned. Its proposed future replacement Group S, for cars limited to 300bhp (so not too far removed from the World Rally Cars of the present day), was also scrapped and tamer Group A regulations were enforced from 1987.

Stuart Turner was Ford’s motor sport boss at the time. “We were so focused on what we were doing that we probably didn’t realise how mad rallying was becoming. It was a crazy formula, but very exciting for everybody involved. Until the accident in Portugal, I don’t think it occurred to us that the sport might be getting out of hand. The cars were so advanced and unusual: I’m not sure I’d have wanted to drive one through the middle of Northampton, let alone a forest.”

Gumpert adds: “I never considered that the cars were too fast – and as an engineer my main interest was to make them go ever more quickly. It was very sad that there were some bad accidents, but in Toivonen’s case one of the contributory factors – to my mind – was the location of the fuel tank, just below the driver’s seat. I thought that a stupid piece of design.

“And as for the spectators in Portugal, the problem wasn’t so much the cars as the lack of control. There were crowd problems in Italy and Greece, too, but you didn’t get that in Sweden or other countries, where the authorities did a better job of keeping people back.

“I couldn’t believe it when they said Group B was stopping. The idea of switching to Group A seemed boring to me – they might as well have told us to run cars with only three wheels.”

Turner, though, felt the news was inevitable. “In some ways it left manufacturers in the lurch at a moment’s notice,” he says, “but I could well understand the decision. I’m not sure I really understood why they’d allowed that sort of category in the first place. Ford had come to Group B later than other manufacturers, so was always playing catch-up. In 1986 the RS200 had more than 400bhp, but with the planned evolution for 1987 John Wheeler [who co-designed the car with F1 engineer Tony Southgate] was talking about 600. Should stuff like that have been rallying? I’m not sure.

“For me the most memorable thing about the RS200 was not necessarily the rally side. We’d been used to so much success with Escorts that finishing WRC events third, fourth or fifth never really captured our imaginations. It was more what happened after the ban, when Martin Schanche and others used the RS200 to such good effect in rallycross. I think that proved the package was all right, but rallying had still become too fast. You can’t just line special stages with Armco.”

Four-time world champion Kankkunen recalls testing for Peugeot in ’86. “The way things were developing,” he says, “it was going to get quite difficult. The cars were moving towards 700bhp and were very light. I was young, very keen to drive and just did my job. When it was cancelled everyone was a little bit sad, but what can you do? It is a little bit like cancelling Formula 1 and making it Formula Ford.

“I was never really frightened, though. If you’re frightened then you are in the wrong job and should do something else. I think horse riding is more dangerous than motor sport. It is up to you where the risk level is. There are drivers who go over the risk level while others can hold it just there.”

The Finn, whose affection for the period is reflected in a private collection of Group B cars (“A Quattro S1, a 6R4 and some Peugeots, although I don’t drive them often”), has recent experience of a current Ford Fiesta WRC – which he tested back to back with a Delta S4. “The Fiesta was nice to drive,” he says, “very precise and simple. Physically the Lancia was 10 times harder, with double the power, a slower gearbox and worse brakes.

“Nowadays the cars are so much easier and safer, it is like being in a kart or sitting on the sofa and using a PlayStation.

“Could modern drivers handle GpB? Yes, but they would have to learn and there would definitely be accidents. When you are old like me, though, the newer car is preferable. I’ve had shoulder, back and knee operations and couldn’t now manage a GpB car for three days – I think that’s the same for all old GpB drivers.

“We could all drive the new cars, though.”

Six decades after Motor Sport's famous continental correspondent Denis Jenkinson ran his Porsche 356 across Europe, it's now racing again following a long and careful restoration

Voice of 90’s motor racing is completing project to revive hidden gems of motor sport film and television.

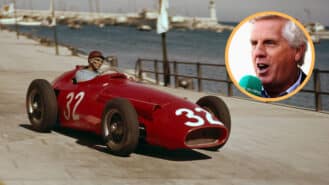

Ferrari's F1 car is set to feature a 'blue livery' at the 2024 Miami GP – we look back on the other times Maranello cars haven't run in red

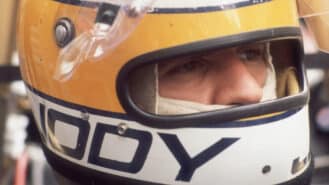

Think of the great Formula 1 champions and Jody Scheckter is unlikely to feature. But, writes Matt Bishop, the 1979 title-winner deserves more acclaim for a career in which he was once the best driver, bar none