Lunch with...Julian Bailey

He’d have liked ‘sensible’ Damon Hill’s Formula 1 career, but Julian reckons he wouldn’t have had nearly as much fun along the way…

James Mitchell

It’s a common complaint that today’s professional racing driver is too squeaky-clean, too focused on his career to have any fun out of the cockpit. His own personality must be subdued by the requirements of PR and brand image, and what little free time he has will be spent in the gym, and certainly not in the pub.

So what happens if a maverick driver comes on the scene who is demonstrably very quick, with the determination to overcome every setback, and the savvy and chat to charm sponsors and do deals, but isn’t prepared to become a slave to discipline, and wants to go on enjoying himself? That’s what Julian Bailey tried to do, and he discovered it wasn’t the way to the top. Today he’s disarmingly honest about where he went wrong.

In the 1980s he was one of a colourful group of young British hopefuls dubbed “the rat pack”. It included Johnny Herbert, Martin Donnelly, Mark Blundell, Perry McCarthy and, on its fringes, Damon Hill. All made it to Formula 1 – more or less, because McCarthy never managed to qualify for a race. The lives of Herbert and Donnelly were blighted by dreadful injuries, but Johnny achieved 144 Grand Prix starts and three great wins, and Blundell drove for Brabham, Ligier, Tyrrell and McLaren. But only Damon Hill became World Champion.

Today, at 48, Julian Bailey has various property interests, including his recent restaurant conversion of a pub in Shere, Surrey. The William Bray has polished wood floors, gleaming decor, portraits of James Hunt and Ayrton Senna on the walls. We meet there for an upmarket burger made from proper beef with lots of cheese and bacon, and chips that taste of real potato. After a serious illness Julian has finally, and with difficulty, stopped smoking, but he still enjoys a good slug of red with his lunch. Looking back, he concedes: “Damon was the sensible one. Well, more sensible than me, anyway.”

From childhood, Julian’s life was unorthodox. At 11 he moved to Menorca, where his parents opened a supermarket. “I never did a day’s school from then on. By 15 I was doing work on the island, whitewashing villas mainly, and putting money in my pocket. I didn’t have much to spend it on, and there was a little kart club there run by ex-pats, so I bought myself a kart.

I was immediately quick – I was about 10 stone lighter than everybody else, and they’d all been propping up the bar before each race, so I was the only one who was sober. I began to think I was really good. So in 1979, when I was 17, I took myself off to England to see what I could do. I arrived like one of those Brazilians who used to come over – I was fluent in Spanish but barely spoke English, knew nobody, just dossed down in a friend’s house in South London.

I went to Brands Hatch and paid £3500, all my savings from painting those villas, to do the Star of Tomorrow Formula Ford Championship. Ten races: crashed in nine, won one. I decided I was a full-time racing driver, but I had to do other stuff to stay alive, ducking and diving. I worked in a pub, picking up glasses, bottling up at night, just casual work, anything I could get.”

His speed in those early FF races did not go unnoticed and, allied to his persuasive powers, got him a chassis out of Crosslé and an engine out of Minister for the 1980 season. All went well, until Snetterton in August. “Enrique Mansilla had an off, came back on, and as we were going through Russell his radiator fell off and went under his front wheels. He lurched into me and I took off. I cleared the debris fence, the car cartwheeled, rolled on my arm and just snapped it, and my helmet came off. They had to cut me out of the wreck. My left leg was broken in several places as well. Three months in Norwich Hospital, and then I had to go home to Menorca to recuperate. I’d been showing quite good promise in the Crosslé. Ralph Firman was talking about a works Van Diemen for 1981. But by the time I got back someone else had got it.

“While I was wondering what the hell to do I saw a picture of an FF Lola, and it looked nice, so I phoned them up. I don’t know how I did it, but Eric Broadley gave me a car. I seemed to have a bit of the Eddie Jordan about me, I could convince people exciting things were going to happen if they helped me. In 1982 I won the Formula Ford Festival, I won the Townsend Thoresen FF Championship, and I should have won the RAC Championship too, except that Mauricio Gugelmin pushed me off.” Relations between Julian and the Brazilian deteriorated as the season went on, coming to a head in the final RAC round at Snetterton. “By then we’d become like Senna and Prost. I only had to finish second to be champion, but I got away first. At Riches he came at me like an Exocet missile, hit me hard, I spun off, and he got the title. Three weeks later, at the Formula Ford Festival at Brands, I was leading the final, and with two laps to go he hit me at Clearways. It could easily have taken us both out, but he cartwheeled into the bank, and I won. He bit through his tongue in that accident, which I always thought was divine retribution for Snetterton.

“I was determined to get Racing for Britain support. I reckoned I deserved it. The public could vote for who should get the RfB deal by sending in a coupon with a £1 postal order. So I went to the post office with £1000 in cash and bought a thousand postal orders, and filled in a thousand coupons using names from the Norfolk phone directory. It was a bit cheeky. But [Racing for Britain director] Steve Sydenham rumbled me, because I spelt King’s Lynn wrong on about 400 forms, which was a bit of a giveaway. Steve rang up a few people and said, ‘Did you vote for Julian Bailey?’ They said they’d never heard of me, never heard of Racing for Britain either. But by the time he worked out what I’d done it was all announced, and I was winning races, so he stuck with me. Out of 25 races I won 15, had five seconds, three thirds, one retirement – and eighth the time Gugelmin pushed me off.

“Money was still tight, and I was still kipping on people’s floors, in anyone’s house who would put up with me. Just eating and surviving. But I didn’t think about the obstacles. If you put up five fences you won’t jump them. You have to jump one fence at a time. Just get up in the morning and say, ‘Today we’re going to do it’. I got a bit of sponsorship from Mike Stevens of Western Models, only about £3500, but it kept me going, and Les Thacker of BP helped me too. He got me into FF2000 for two seasons with a Reynard. I loved those cars: once I was on wings and slicks, I felt I could walk on water. The weekly comics said I was ‘blindingly fast, but erratic’. That was OK with me, because you can move on from that. You can always tidy yourself up, but if you’re not fast in the first place you’re nowhere, you won’t get quicker.

Brancatelli joined Blundell and Bailey at Nissan for Le Mans in 1990, and crashed the car

Motorsport Images

“I won the Grandstand series in 1983, and in ’84 I was runner-up in the British Championship to Maurizio Sandro Sala, but there were some accidents too. There was a big one at Brands with Martin Donnelly. I tried to pass him at Paddock, in the wet, and he just drove into me. I thought it was his fault, he thought it was my fault. I was furious, and as we got out of our cars we came to blows. I came to even worse blows later when Martin’s Irish mechanic, Mickey, tried to beat me up. Bit volatile, was Mickey.

“It was time to move on to Formula 3, and I did it with Dave Price. Pricey knew I didn’t have a pot to piss in, but I told him he’d get paid eventually, and he did. Eventually. We got a chassis from Reynard, but we didn’t pay for that. I still don’t know who did pay for it. I got an engine out of VW, and they gave me a road car too. Adrian Reynard introduced me to a commodity broker he’d met on the ski slopes, and I told him I was going all the way to F1. If you believe in yourself it’s infectious, you can take people along with you. So the name of his firm, Braemar, went on the car. It wasn’t mega money, but it kept me racing.

“But I never did well in F3, never won a race. When the money ran out and Pricey wouldn’t run me any more I went to Madgwick Motorsport, Robert Synge’s outfit. They were using the Saab engine, and it was pretty dire. Then I joined Swallow Racing, which was based in Leicester, running Ralt-VWs. Through them I met Paul Carnill of Cavendish Finance, who was doing pretty well out of an unsecured loans business. I went to see him in Nottingham, met him in a sort of gentleman’s club, and told him I wanted to do Formula 3000. ‘’Ow much will that be?’ he says. I said, ‘If I could just do the three British rounds, it’d be £70,000.’ ‘That’ll not be a problem,’ he says. He was making 50 grand a week, so it wasn’t much to him. F3000 used Cosworth DFV engines then, so they were like an earlier-generation F1 car, with 500 horsepower. I tested the GA Racing Lola, run by Mike Collier, at Snetterton, and I was quick straight away. First time through Russell everybody was convinced I was heading for a big accident, but I loved it. With that power-to-weight it was like getting back into Formula Ford, sliding everywhere. Donington was the first outing, and the race was going to last 75 minutes. I’d never done a race that long before. I qualified eighth, but I was so nervous I did my belts up too tight, cut off the circulation, and my legs went dead. I ran in the top six, but I had to stop after 40 laps. I was fourth at Enna three weeks later, and then at Brands I crashed the thing in practice. But come the race I led from start to finish, ahead of the works Ralt-Hondas and everybody. It was the first time a Formula 3000 race had been won by a Brit.”

Brands Hatch circuit boss John Webb had always been a Bailey supporter. “In my ducking and diving efforts to stay afloat I used to sell things to Webby. I’d source anything I could: his printing, the tables in the Kentagon. That day a guest in his box was Ken Tyrrell, who always liked to keep an eye open for new talent. I’m sure John did a selling job on Ken for me. But I didn’t hear anything. That winter I was on the sofa again, wondering what to do next – knowing that a full season of F3000 was going to cost a hell of a lot – and I gave Ken a call. I told him, ‘I’ve got half a million pounds for you.’ He said, ‘I don’t believe you. No British driver has half a million pounds.’ Well, I’d been running a pub with my brother Adrian, we’d borrowed £170,000 to buy it and it was doing well. I knew I could sell it for 500 thou, which would clear about £300k. I reckoned I could get £150k from Cavendish, and £50k from Braemar. So I went down to see Ken in Paul Carnill’s new Bentley, which helped convince him. My brother agreed to lend me his share of the proceeds of the pub, and I was in Formula 1.

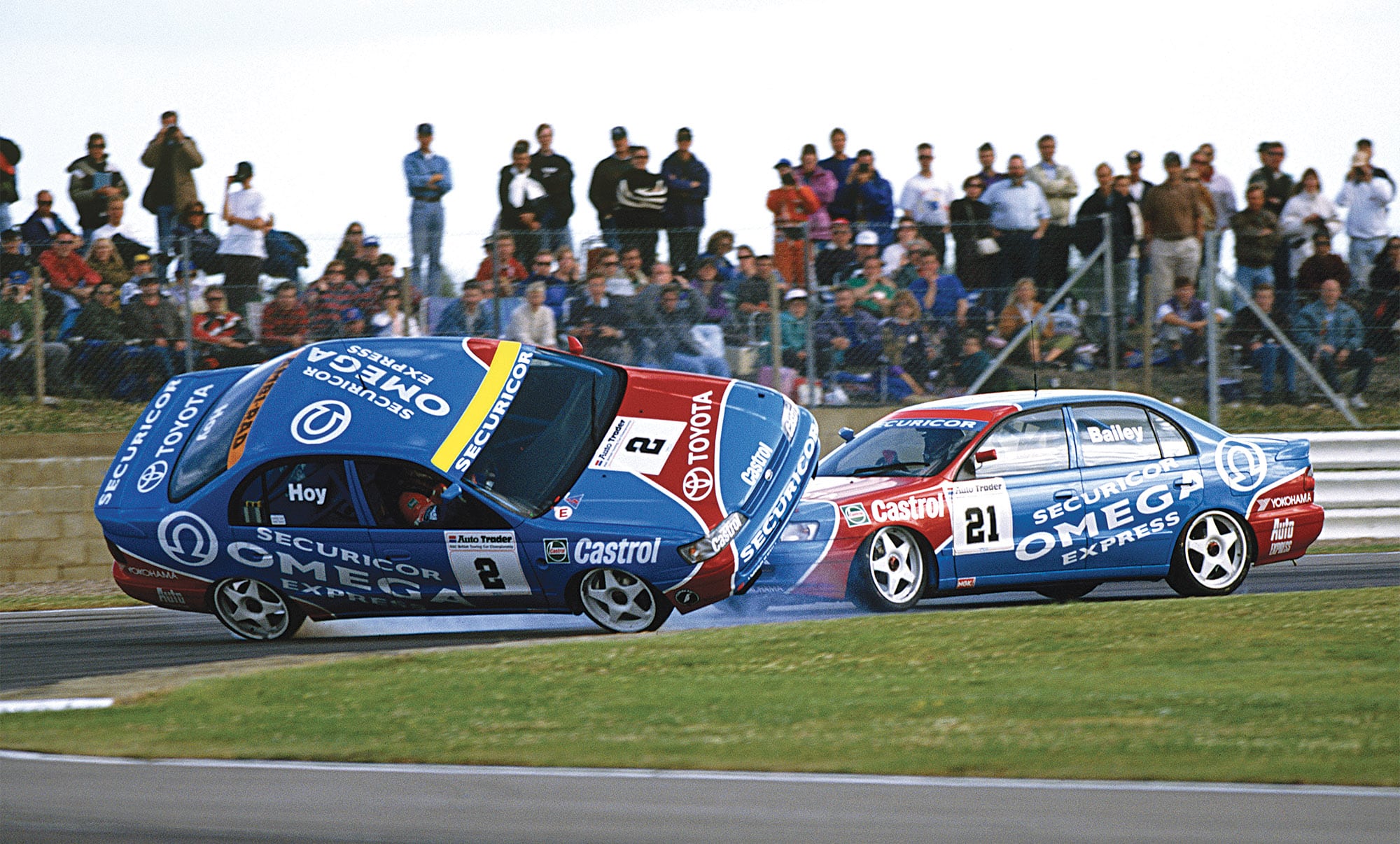

Running into trouble with BTCC team-mate Will Hoy and Toyota at GP support race

Motorsport Images

“The car was no good, of course. Jonathan Palmer managed to make it work a bit – he was in his fifth year in F1, and he’d won the Jim Clark Trophy the previous season for top non-turbo driver – but driving for Ken Tyrrell was a bloody nightmare. He was totally autocratic: it was his way or no way. First race, Rio, I didn’t even qualify. Then at Imola, Tamburello, which was just a kink then, should have been easy flat. But the car was moving about so much I could barely do it. I told Ken, ‘It hasn’t got enough downforce.’ ‘Rubbish,’ said Ken, ‘every driver says that when he gets to F1.’ He dismissed it completely. Turned out we were running so little wing, our top speed was quicker than the Ferrari turbos. That’s how wrong he was.

“In Rio the heat and humidity were stifling, and all the other teams had their air-conditioned units with proper catering, except us. We’re squatting in the garage, dripping sweat into the puddles of oil, and Norah Tyrrell’s making sandwiches. ‘What do you want in your sandwiches, ham and tomato, or just ham?’ This was Formula 1. I said to Ken, ‘Can’t we have one of those air-conditioned units?’ He said, ‘If you pay for it, we can.’

“Ken had been around a long time, he’d won all those championships with Jackie Stewart, he’d seen it all, done it all. He took cost-cutting to an incredible level. If he opened a bottle of beer he’d put half of it in the glass and the rest in another glass, so it would do two people. But he was dead straight. I said to him once, ‘Ken, do you believe in God?’ He said, ‘I don’t know about God, but if you follow the Ten Commandments you won’t go far wrong.’ He was always very critical, and you had to be thick-skinned to drive for him. At Jerez I remember him saying to Palmer, ‘When Senna comes round that corner, he looks as though he’s going to go off. When you come round that corner, you look as though you’re coming into the pits.’

“In Detroit I had one of the worst races of my life. The drinks bottle had fallen off and, although I managed to keep going, I wasn’t fit enough and by the end I was dehydrated and completely exhausted. After nearly two hours round the streets I was in eighth place, with three laps to go, and I lost it, hit the wall. When I trudged back to the pits Ken picked up my packet of fags and threw them over the pits and into the paddock. They landed on the back of the Benetton truck just as it was driving away. So not only was I knackered, I had to run after the truck to get my cigarettes back. Ken said, ‘You’re in Formula 1 now, so give up smoking.’

F1 breakthrough came with Tyrrell in 1988, but Bailey failed to qualify at Spa

Motorsport Images

“At Silverstone I out-qualified Jonathan, but my main claim to fame at Tyrrell was in the Friday wet practice at the Hungaroring. I was quickest for most of the session, ended up third behind Mansell and Nannini. But of course it dried out – and I failed to qualify.

“I had zilch at the end of that year. Ken needed more money, Alboreto arrived with money. It was a shame because Harvey Postlethwaite had arrived, the 1989 car was going to be much better, and I would have loved to race a car designed by him. Back on the sofa again – and then I had a call from Eric Broadley at Lola. He was building a sports car for Nissan, and would I like to drive it?

“That was the start of the two happiest years of my life. The team was based at Milton Keynes, run by Howard Marsden, a very courteous, erudite Englishman. It was the first time I’d ever been paid as a driver. For 1989 I got £100,000 plus a road car. The next year, before I went to see Howard about my contract for 1990, I was talking to Eddie Jordan the day before, and he said, ‘You should screw them for more than that.’ So I told Howard I wanted to stay, but I’d been offered £150,000 by Porsche. ‘No problem,’ he said, ‘we’ll add another fifty to your contract. We like our drivers to be happy.’ Of course I hadn’t been offered anything by Porsche. I drove back down the M1 in my Ford Sierra RS500, moonstone blue with a phone in it, and I thought I was king of the world. That year I paid my brother back his share of the pub sale proceeds.

“Keith Greene was team manager, and my team-mate was Mark Blundell. We got on really well, flying around for the World Sports Car Championship rounds. We stayed in the Beverley Hills Hotel, Mark and me lounging by the pool like superstars. To make each other look important I’d go up to my room and phone him, so he’d get paged, and then he’d do the same for me.”

Julian’s first Le Mans race was an embarrassment, because he crashed the car – four laps into the race. “I nearly got sacked for that. We had a bit of a braking problem anyway, but right after the start I got up to third place and was catching John Nielsen’s Jaguar. Going down the Mulsanne Straight, over 240mph, I got too close to him. When he braked I braked, got sideways, hit him up the rear, and broke the chassis. I didn’t realise, at those speeds, you have to anticipate a little. If he hadn’t been there I’d have made the corner. But I kept my drive because they had proper telemetry on the car for the first time, and I was the only driver in the team who was taking the Mulsanne Kink flat. Then at Brands I was going really well, and took second from Jo Schlesser’s Sauber-Mercedes round the outside of Paddock. I suppose I got a bit too big for my boots, because then I threw it into the bank at Clearways. After that they stood me down for a race, to slap my wrists.

Scoring his sole F1 point aboard the Lotus at Imola in 1991

Motorsport Images

“At the end of 1989 the Japanese wanted a scapegoat for the team’s lack of success, so they fired Keith Greene, which really wasn’t right. They brought in Dave Price instead. The second year at Le Mans, Mark and I were really there to win. We wanted three quick drivers in our car, we wanted Donnelly to be with us again, but Pricey wanted to even the cars up. I argued with him about that, but we got Gianfranco Brancatelli as our third driver. We started on pole, and we were leading during the night when Brancatelli crashed into another car in the pitlane, and we were out. I finished third at Spa with Kenny Acheson, and Mark and I were third at Dijon, second in Montréal and second in Mexico. It was meant to be a five-year programme for Nissan, but at the end of the season Peugeot came in, the rules changed, and Nissan pulled the plug. Back on the sofa.

“I had a friend who had just sold a big confectionery business, he had a few millions, and he offered to buy a percentage of Team Lotus for £500,000 – provided I was the driver. Lotus was in a bit of a state by then, and it was all a bit iffy, but we got the deal done, to drive alongside Mika Häkkinen. At Hethel we had a big contract signing with Mont Blanc pens and all that, and then they sent someone upstairs to get my new Team Lotus overalls. He must have picked up the wrong set, because he came down with a brand new set with Johnny Herbert’s name embroidered on them. When he realised his mistake he looked extremely embarrassed, and went back and got my overalls.

“I worked out later that they were always going to have Johnny, but he had to miss the first few races because he was contracted to do Formula Nippon. So they conned me, really. I got to do the first four races: in Phoenix the car caught fire, and when I brought it into the pits they jacked it up and a wheel fell off. That was just in practice. At Imola I started 26th, but it was wet, and by lap 14 I was up to sixth place. Might have finished higher, but [Lotus team manager] Peter Collins knew they’d left tape over the brake ducts and was worried the brakes would catch fire. So he called me in. Of course I ignored him, I didn’t want to stop, but he was literally hanging over the pitwall waving me to come in, and I thought they might know something I didn’t, so I stopped for them to tear the tape off. But I still finished sixth – the one World Championship point of my career. Then we went to Monaco, and I was crap.”

On Thursday Julian brushed a barrier at Portier, on Saturday morning he hit the barrier at Ste Devote, and on Saturday afternoon in the spare car he hit the barrier at Loews. “I never really got Monaco, even in F3 I couldn’t handle it, I don’t know why. Macau, which I did in F3, was ten times harder, but I loved Macau. Then Johnny was in from the next race, Montréal. That was when I realised F1 was finished for me. Fortunately my mate hadn’t put in his half million, but he had spent £150,000.

Successful spell at Lister included becoming FIA GT champion in 2000

Motorsport Images

“All I could get was the British Touring Car Championship. I had to beg, steal and borrow to get that Toyota drive. I found it terribly difficult to start with: it felt like such a comedown after F1, and I’d never raced front-wheel drive before. I told the Toyota bloke, Paul Rusbridger, I’d bring this money and that money, so I got the drive, and then I didn’t bring the money. But in 1993 it became a proper works team, and I was paid £35,000 plus a road car. I ended up doing the British, South African and New Zealand championships, and in my best year I earned £180,000. In the end I really liked BTCC. That was its heyday, with BMW, Ford, Nissan, Vauxhall, Renault, Peugeot, Mazda. The atmosphere was friendly, and the cars became more sophisticated and nicer to drive. My worst moment was when my team-mate Will Hoy and I were leading at the British Grand Prix meeting, and I took him off. He rolled it. One of us would have won, and a Nissan won instead, so it didn’t go down well. I got a serious bollocking for that. Toyota sent me a formal written warning, and said they wouldn’t pay my wages for the Spa 24 Hours a few weeks later. So I said, ‘If I win the next BTCC round, will you pay me for Spa?’ They agreed to that, so I put it on pole for the next round, at Knockhill, and won it. At Spa, which was a GT race with Porsche RSRs and stuff, we were lying third at midnight when the suspension broke.

“I did three full seasons with Toyota, and then at the end of ’95 Inchcape, Toyota GB’s owners, decided racing was a waste of money. So I got involved with Laurence Pearce and the Listers. Laurence is a character, a bit of a lunatic, but we hit it off, and it was a fun time. The whole Lister GT racing operation was driven by him alone. We went all over the place, and I got paid as well. The car was a big front-engined monster, nice to drive, but that Jaguar V12 just pumped heat into the cockpit. Sometimes in a long race I felt I was going to explode with the heat, perform spontaneous combustion. The soles of my boots would melt, and stick to the pedals.”

Bailey was reunited with Blundell at Le Mans in 2002, driving the MG Lola EX257

Julian did 56 races in the Listers, as far afield as Pikes Peak and Brno, Las Vegas and Lausitzring, and he won a lot of them. In 1999 he was British GT1 champion, and in 2000 he was FIA GT Champion, winning six of the 10 rounds, including Valencia, Estoril, Zolder, Magny-Cours, and the British Empire Trophy at Silverstone. “I did five years with Laurence, and what sticks in my mind was not so much the races as the fun we had. Laurence used to lose his rag all the time, chuck his sandwiches across the room. The Americans, always so polite and courteous, they didn’t know how to take him. Once we were arguing about tyres, and he threw me into a wheelie bin. I was stuck, couldn’t get out. Laurence kept that team going for a long time – one of his sponsors was Newcastle United football club, they paid for a lot of it.

“In the end, if you can’t make it in motor racing it gives you up. Drives keep coming while you’re good enough but, as you get older, younger hotshoes come along. In the end I just decided not to pursue it any more. I saw an opportunity to build some houses, then I built some more. I’d seen people outside motor racing make so much money, and I decided that was better than sitting on the sofa waiting for the phone to ring.

“When I was racing I never bothered with fitness regimes, I kept in shape by driving all the time. After I stopped I carried on smoking and drinking just as much, and it almost killed me. I had a stroke about a year after I gave up racing. Having a stroke in your forties is a wake-up call. Now I have to go running and swimming, and I’ve had to stop the fags.

“I got involved with the Top Gear TV programme for a few years: I was The Stig, anonymous behind the helmet, and it was all meant to be a big secret, but lots of people in racing knew it was me. We had some fun with that.

“My stepson Jack Clarke is doing Formula 2 now, and that’s pulling me back into things. Jack did a bit of karting, then Formula BMW and Formula Palmer Audi. I give him input, but it’s very hard to stand outside and comment on somebody’s driving. When Senna and Prost were in a corner you’d have said Senna was quickest, Prost was slowest. But the watch told you Prost was as quick, maybe quicker.

“Of course, I’d have liked to have Damon’s career. But I did make plenty of mistakes, a lot of them off the track. Smoking and drinking should have taken a back seat to help my career. But you do what you do, you are the character you are. And I still reckon I had a lot more fun than Damon did.”